Word docs

KS1, KS2

Years 1-6

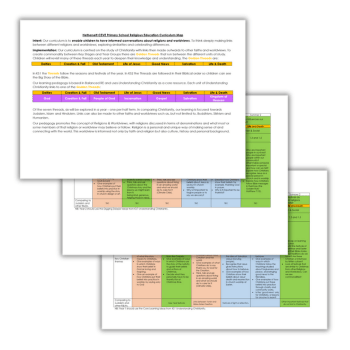

This RE curriculum and curriculum map example from Hethersett CEVE Primary School, created by Matthew Lane, aims to enable children to:

- have informed conversations about religions and worldviews

- think deeply, making links between different religions and worldviews

- explore similarities while celebrating differences

The RE curriculum is centred on the study of Christianity with links then made outwards to other faiths and worldviews.

To create commonality between Key Stages and Year Groups there are Golden Threads that run between the different units of study. Children will revisit many of these threads each year to deepen their knowledge and understanding.

These Golden Threads are:

- Deities

- Creation & Fall

- Old Testament

- Life of Jesus

- Good News

- Salvation

- Life & Death

In KS1 the Threads follow the seasons and festivals of the year. In KS2 the Threads are followed in their Biblical order so children can see the ‘big story’ of the Bible. Read more about the creation of this RE curriculum below.

Why our RE curriculum focuses on commonalities, not differences

In 2018, the Commission on Religious Education delivered its final report that recommended a new vision for the subject.

Firstly, the report provided a completely new way of framing the subject as ‘religion and worldviews’, rather than religious education.

The rationale for this change is very interesting – I recommend reading the Commission’s final report.

The second major change was the use of different ‘disciplines’ to study religions and worldviews. In response to these fundamental changes, many SACREs (the local bodies that set RE curriculums) have updated or released new locally agreed syllabuses.

Theology, philosophy and human and social sciences

The biggest change within my local syllabus here in Norfolk is the introduction of a disciplinary pedagogy that asks children to study RE using the skills (or ‘lenses’) of:

- theology

- philosophy

- human and social sciences.

Theology is thinking about believing and asking questions that believers of a faith may ask. Children explore questions from inside religions.

Philosophy, or the study of ideas, is about pondering “the nature of knowledge, existence and morality more broadly”. This means including ethical questions and debates.

The final lens – human and social sciences – explores the ‘lived experience’ of members of a religion and what happens when theology meets everyday life. As these names are quite the tongue twister, we call them ‘believing’, ‘thinking’ and ‘living’ in my school.

Norfolk schools were also given freedom to design their own units and courses of study. In preparation for looking at our current RE curriculum I first discussed it with the children.

One pupil said, “I like doing our stuff but it’s interesting to see their stuff and see how different people live.” Having heard their thoughts, I threw the old curriculum in the bin and started afresh.

‘Other people’s stuff’

The school where I work is a typical Norfolk village school. It’s over 90% white British and Christian or of Christian heritage. Some children’s parents, and even grandparents, were also pupils here.

I knew that I didn’t want our new curriculum to involve the children doing a unit of “their stuff” (Christianity) followed by an entirely different unit of “other peoples’ stuff” (any other religious or non-religious practice).

Our world is becoming more fractured. If children are to see the beauty and value of other people, religions and worldviews, they need the skills to appreciate them and, most importantly, ways of connecting with them.

This got me thinking about exploring: if you know where you’ve been, it gives you a good basis to explore the new.

So I decided to be bold: every unit of learning would start with Christianity. We would learn about what we already knew, or thought we knew, and then link outwards.

Finding links and connections between Christianity and other religions and worldviews would form the bedrock of our curriculum.

Key questions

This new curriculum would follow the Bible as its basic structure, with three half-terms exploring concepts rooted in the Old Testament, followed by three half-terms of New Testament content.

This proved to be very helpful as it dislodged Easter and Christmas from the times we celebrate them (there is no acknowledgement in the Bible when these events took place).

This structure was inspired by the Church of England Education Office’s brilliant Understanding Christianity project. As we are a church school, at least 50% of our RE content should focus on Christianity.

Therefore, the first three or four lessons of each half-termly unit have a Christian focus and usually contain theological study of the Bible.

This gives time to explore our ‘key question’ and reflect on how Christianity answers it. Having built a solid knowledge base in Christianity, learning then moves on to one or more other religions or non-religious traditions for comparison.

How it works

For instance, in autumn in Y6, children explore Genesis one and two pondering the philosophy key question, ‘Why was the Earth made?’.

Children recap the key events of these chapters and then debate and discuss how women are described in markedly different ways between chapter one and two (they were written at different times by different authors, then collated together at a much later date).

A lesson is spent looking at the scientific description of how the Earth was formed and what similarities this has to Genesis.

This is not an apologist attempt to explain Genesis, rather a time to discuss what real ‘events’ humans wrote into the Genesis story and why we think this coincidence could have occurred (the importance of water to life), to explore what makes no scientific sense (light is created before the sun) and what this tells us about the writers of Genesis and the time and the audience they wrote for.

It is a good time to discuss how correlation does not imply causation.

To conclude the unit, we spend two lessons exploring the events of the Hindu creation story and its expression of our universe as one in a string of many.

Children quickly spot the beginning of the world in darkness and water and how a prime mover is needed to bring light and life into the world.

This is the most important part of the new curriculum: children begin by finding and celebrating what is the same and then question why they are the same.

How can two religions from different sides of the planet have similar beliefs? How can two faiths that appear so different actually be quite similar?

Time and energy

Growing this new curriculum and pedagogy has taken time and lots of energy from the amazing staff at my school.

As we move further towards a ‘religion and worldviews’ curriculum, our emphasis will be on denominations and how, for instance, there is no single ‘Christian worldview’.

The aim is that children can see how worldviews ‘similar’ to their own can actually be very different, while the superficially ‘different’ can be very similar.

What is a ‘worldview’?

‘A worldview is a person’s way of understanding, experiencing and responding to the world. It can be described as a philosophy of or approach to life. This includes how a person understands the nature of reality and their own place in the world.

A person’s worldview is likely to influence and be influenced by their beliefs, values, behaviours, experiences, identities and commitments. It can be influenced by organised systems of thought and these can be religious (Christian, Hindu, etc) or non-religious (Humanism, Secularism) in nature.’

RE Council Final Report 2018

Matthew Lane is the Religious Education lead at Hethersett CEVC Primary School. Find him at theteachinglane.co.uk and on Twitter at @MrMJLane. Find out more about the Reforming RE project at ReformingRE.wordpress.com.

How to decolonise your RE lessons

Making sure your RE curriculum is aware of colonial influences on religion is tricky. Here are some common mistakes and how to avoid them…

I have spoken to so many primary colleagues who teach their school’s RE curriculum. It feels that a high proportion feel really insecure about their lack of subject knowledge and making mistakes.

I am trained for secondary RE, but I made some catastrophic mistakes early in my career. I learned lessons that I think are relevant across phases.

One thing I think we do really well as RE teachers is to ensure our curriculum is as inclusive and representative as possible. We try our best to make classrooms, lessons, displays and resources representative, diverse and multicultural, starting to break down the stereotypes and misconceptions.

Being inclusive in our teaching is not just about RE though, it is a whole-school responsibility. If children learn about diverse authors and positive historical, scientific, literary figures who look like them, and see the celebration of their achievements, it will inspire them to push beyond institutional racism. A diverse cohort of staff to act as role models can have a similar effect.

But I wonder how many of us feel equipped to offer an authentic RE curriculum in this way, whether this is using the right language and pronunciation or reflecting the spectrum of perspectives within a religious or non-religious worldview?

If we’re lacking the right knowledge or tools, how can we decolonise the RE curriculum? More to the point, what does that even mean?

Decolonising the RE curriculum

Please don’t think we need to throw out all our resources and start again – we’re all short on time! But we can start making small, manageable changes that can have a huge impact.

And it doesn’t matter if we don’t get it right straight away. Awareness is powerful. We are interested in how the colonial lens influences our RE curriculum.

Please also note that there must be no judgement at all. The impact of colonialism is so entrenched that it affects most of us in some way, albeit often unconsciously. It is in no way a reflection of who we are as people.

In short, Britain colonised other countries and represented the people, cultures and religions in these colonies incorrectly, either through ignorance or design. Our job as RE teachers could be to update our language to replace these inaccuracies. Here’s how!

Hindu Dharma

One simple way of decolonising our curriculum is to use the term Hindu Dharma instead of Hinduism. India, at the time of its colonisation by Britain, contained a diverse set of beliefs.

The British colonials attempted to put these beliefs into a Christian framework rather than understanding the authenticity of what was already in place.

This means that British colonials used the word Hinduism to categorise and homogenise the diverse beliefs and practices of Indians (Hindu from the Indus River; ism meaning belief).

But there are other small changes we can make, too. For example; use Mandir not temple when referring to the holy building in Hindu Dharma, and use Varna rather than Caste. Varna is based on your virtues; Caste is based on your birth right.

Use the word Murti rather then idol, and refer to Brahman as an ultimate reality, not God. Every Hindu has a different reality in relation to the divine, so Hindus are sometimes atheists, sometimes monotheists, sometimes polytheists, and not all Hindus are vegetarians!

Sikhi

Could we use Sikhi (pro. sickee) and Sikh (pro. sick), as opposed to Sikhism (pro. seek-ism)? Sikhna is a punjabi word which means ‘to learn’. Sikhism is a noun which suggests a fixed set of beliefs.

Sikhi is a verb which loosely translates as ‘learning to be human through lived experiences’.

You can see how a western Christian lens has been used to define something differently to what it actually is.

Guru Nanak is pronounced Nar-nak. Siri Guru Granth Sahib (pronounced. sub) has ang (limbs) not pages, as it is a living Guru not a holy book.

The Gurdwara is not so much a religious building as it is a place to engage with the Sri Guru Granth Sahib. We could use ways of thinking rather than beliefs when referring to the teachings of the Gurus, too.

Finally, people often translate Il Onkar as ‘there is one God’, but a more authentic translation is ‘everything is one’.

Christianity

Christianity has an uncomfortable connection to colonisation. It is the religion of the British empire and has been since the emperor Constantine appropriated it for his own means.

Also, the Church has historically benefited from the slave trade. Before that, Christianity was, under the rule of Rome, an illegal band of rebels following the teachings of a leader, who, again under the anti-Christian rule of Pontius Pilate, was effectively a convicted criminal – Jesus – a Middle Eastern man.

Saying ‘Jesus is Lord’ in the time of the Roman Empire was literally a revolutionary statement. How could this impact your teaching of Christianity?

I teach lessons on Jesus in terms of how he challenged the culture of the day – how he treated women, how he broke rules.

The Chosen on Netflix is a really authentic look at the person of Jesus in his historical, political and religious context. Very different from the blue-eyed serene Jesus we often see in western art.

Judaism

It may feel obvious, but not all Jewish people have the same history. So, do we truly reflect the diverse history of Jewish people from around the world?

Do we know that Christians created the word Judaism, and the word religion was created in the 13th Century?

Do you know that the Book of James in the Bible is called the Book of Jacob (Jesus’ brother) in the Hebrew Bible, but the mistranslation stuck when King James wanted to name a book after himself? That Jesus’ original name was Jeshua – he was Jewish so had a Jewish name; or that Mary was Miriam?

These names have been colonised to make them sound more ‘white’. Could we use the authentic names?

Islam

The Shahadah states ‘There is no God but Allah’. So, when teaching Islam, we could simply use the word Allah as opposed to God. And Allah is loving and compassionate, so Islam is a religion of love and compassion.

The new generation may not be impacted by Islamophobia in the same way as the older generation. Yet, many feel the Prevent strategy is biased against Muslims and silences young Muslims in classrooms out of fear of being reported.

Please also be aware that Islam resources are often Sunni bias. Can we include facts about Shia Muslims who pray three times a day, or Sufi Islam which is the mystical branch of the religion?

Buddhism

The word enlightenment is a western term. It’s more authentic to use the word awakening. Buddha wasn’t necessarily a single historical character, either. Rather the word Buddha means ‘one who is awakened’. Like the concept of messiah in Christianity, there were many Buddha throughout history.

I am guilty of teaching more palatable parts of Buddhism like meditation and ignoring the messier parts like the Buddhist persecution of the Muslim Rohninya people in northern Myanmar.

I also wrongly use Buddhism to challenge the criticism that religion is all about believing in things that are commonly thought of as ‘irrational’ (like God and an afterlife). Using the word enlightenment makes Buddhism sound more ‘rational’.

I hope this breaks down some simple, easy-to-apply ways of being more inclusive and representative, and decolonising the RE curriculum so that our teaching can be even more authentic.

Louisa Jane Smith is an RE teacher with more than 20 years of experience. She started The RE Podcast in October 2020 as a free weekly resource for teachers and students of RE. Follow Louisa on Twitter @TheREPodcast1 and see more of her work at therepodcast.co.uk.

How to build a powerful RE curriculum

From storytelling to extended writing, use these tried and tested strategies to put together a truly effective RE curriculum…

RE (religious education) is probably the most variable element of the curriculum across the whole of our education system.

There is little else on the timetable that varies so much in quality, quantity, and content from school to school.

Other subjects are standardised by the outline given in the National Curriculum, but RE appears in only one line, to inform readers that it must be taught in all state schools.

Instead of a National Curriculum there are locally agreed syllabi, a form of curricula-by-committee which, far from being standardised nationally, are different across every local authority (all 333 of them in England).

Broadly speaking, if you are in a local authority school, you are obliged to follow yours. If you are a free school or academy, you have a great deal more freedom over what you choose to teach.

Freedom, of course, sounds brilliant, but if you’re an RE lead or a curriculum lead without a background in theology (and religious studies and philosophy and sociology and anthropology), it can be quite daunting.

If you really are starting from scratch, then it is worth taking a look at some different locally agreed syllabi to get a feel for what a broad and balanced curriculum will look like. (Norfolk is a good place to start.)

I am fortunate (or unfortunate) enough to have a degree in theology and philosophy, and I began my teaching career as a secondary RE teacher.

A few years ago, I moved to the primary sector and have developed an RE curriculum for my school which we’re now going into our third year of teaching.

Religious education in primary schools

RE can, and should, be a powerful subject for our pupils to learn about. Done right, it can open up the world for our children, give them insights into cultures and systems of thought that are different from their own, and make them more curious and well-informed about the world around them.

So, what is it about RE that makes it powerful?

RE takes our students beyond their personal experiences – over the course of a year we can open pupils up to Hindu ideas about life and death, the pilgrimage of Hajj to Mecca, Christian debates about violence and war, and the story of the life of Buddha and what that means to millions of Buddhists today.

The immediate practical applications of this knowledge might seem a bit hazy, but they make the world a richer and more interesting place for children to exist in, by building up an intellectual worldview where different cultures and conflicting ideas sit alongside students’ own.

That is the power of RE.

How to plan a curriculum

1. Take a bird’s-eye view

The first thing you need to do, before anything else, is make a long-term plan. If you’re the RE lead or curriculum lead, then you have the exciting prospect of doing this for the whole school, but if you’re a classroom teacher, then you need to know at least what you’ll be teaching all year.

Everyone will be in a different position here. If you’re working from an existing scheme or a locally agreed syllabus, then you will have units of work ready to go.

If you’re starting from scratch, then this is probably a more daunting prospect, but essential nonetheless.

2. Lay it out

Find the biggest table in your school and get a group of interested folks together to lay out your curriculum.

Write each unit on a note card, then add the five most important ideas in each unit, and then start to lay out your RE curriculum from EYFS all the way through to Year 6.

By doing this, you can begin to see the lines that run through the subject. If we are going to teach Easter in Year 3, have we already introduced ideas like the Gospel, Jesus and sacrifice before that?

Shuffling the cards around will help you think about a sensible sequence for teaching.

3. Break it up

Now we need to take it from the planning table into the classroom. There are so many tools at your disposal to break up the big ideas in RE into interesting, digestible chunks, so here’s a few I’ve used in our curriculum:

- Storytelling – RE is full of stories that tell us something about religious beliefs and what we have in common across human cultures. We can read them, retell them, act them out, summarise them and ask questions about them.

- Reading – be it whole-class guided, paired, echo, or individual reading, RE is a great chance to read and then discuss. It can sometimes be difficult finding accessible texts. I find it useful to rewrite magazine or newspaper articles, or to use Bible stories designed for Sunday school with a bit of an edit to remove their explicitly evangelical overtones.

- Debate – the big ideas in RE, of course, lend themselves to a bit of debate, but it’s worth doing properly. Lay the groundwork, ask what kind of knowledge students need to have before they can come to meaningful opinions on topics, and try to ask what real people in the world believe on these topics, rather than focusing only on what we as teachers may think.

- Writing – across all our foundation subjects, we emphasise the skill of extended writing. Starting in Year 3 we have heavily scaffolded the process of writing paragraphs at the end of each unit. Over the course of KS2, we remove a lot of that scaffolding which means our Year 6s can plan and write some very impressive mini-essays that reflect their engagement with the knowledge they come across in RE.

4. Stick to a format

When it comes to actually doing the planning, it is worth deciding early on what you think will work for your context.

You need to answer some basic questions: how much space will RE have in the timetable? How are you going to assess it? And how do you think lessons will flow?

For the scheme I wrote, we followed other foundation subjects in using booklets and PowerPoints to scaffold lessons.

Teachers have all the key knowledge and examples there in the presentation, and students use the booklet to answer questions and recap knowledge.

In KS1 we began using booklets but found that they didn’t add a huge amount to the lessons, and so now we mostly stick to storytelling, discussion and teacher-led reading.

Deciding on a common format for your planning will mean you get into a good rhythm, where one unit builds on the format and the successes of the last one.

5. Get everyone on board

Take everyone with you when it comes to RE. When you start the planning process, try to find a group of teachers who want to be involved in laying the groundwork.

From there you can spread that enthusiasm outwards through to everyone who will be teaching the subject. CPD is obviously a great place to start, but it can sometimes give the impression that things are being imposed from on high.

Honest discussion with colleagues, no-stakes coaching, listening and acting on feedback are how to get everyone on board.

Subject knowledge is often a big stumbling block to teachers feeling confident in RE, so do the hard work for them: include extra background knowledge in the planning and make suggestions for some short reading – Very Short Introductions from OUP, and Karen Armstrong’s books on religion are good starting points.

Adam Smith is a Year 5 teacher and RE lead at Charles Dickens Primary School in Southwark, London.