GCSE English Language revision – Best 2025 resources and ideas for teachers

Help prepare your Year 11s as best as possible by easing any exam pressure with helpful study tools…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

It’s that time of year again. You want to help students with their GCSE English Language revision, without piling on the pressure.

If you can help them to revise in a way that doesn’t feel like a non-stop conveyor belt of information passing in one ear and out the other, you’ve made a decent start.

We’ve rounded up a selection of tips, tricks, games, worksheets to help with this year’s English language GCSE paper. Check them out to see if anything might help your class study more effectively and efficiently.

(We also have revision resources for GCSE English Literature.)

JUMP TO A SECTION:

- Classroom resources

- Getting students to revise

- Run a ‘lecture style’ intervention programme

- More GCSE English revision techniques

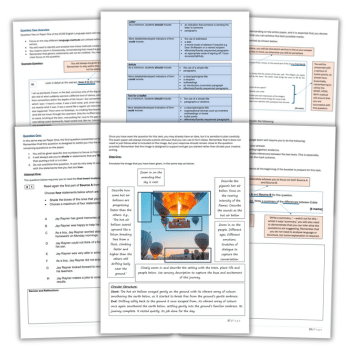

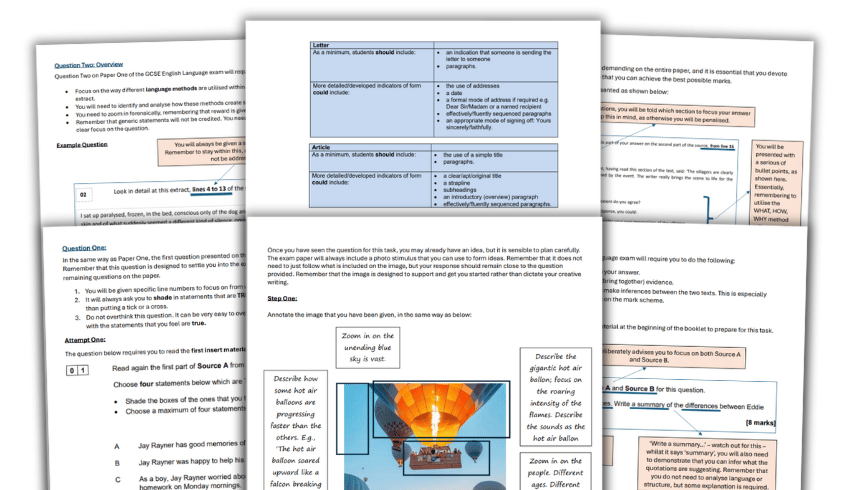

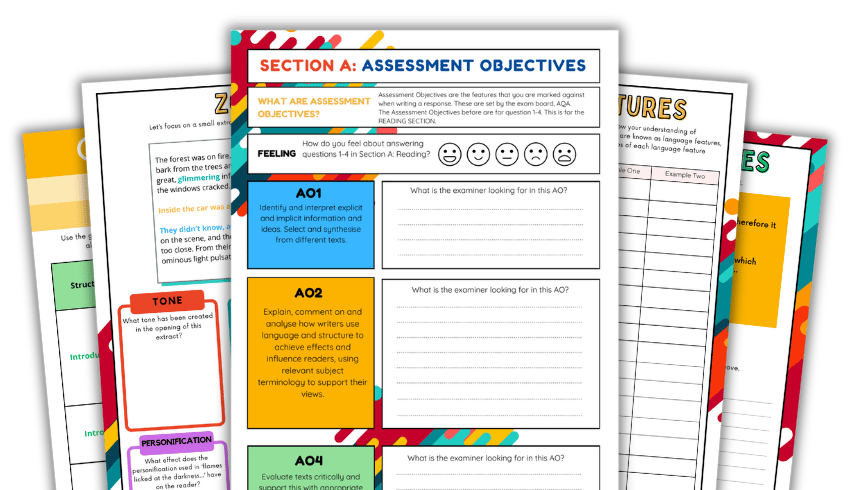

AQA English Language revision booklets

These free AQA English Language revision booklets contain structure guidance for Paper 1 and Paper 2. They also contain overviews of all questions, with advice and exemplar responses, plus practice questions for students to have a go at.

English Language Paper 1 revision booklet

This free, 70-page, teacher-made AQA English Language Paper 1 booklet will help your students revise each question on this particular paper. Its bright and appealing design will appeal to your pupils. We also have an AQA English Literature Paper 1 revision resource.

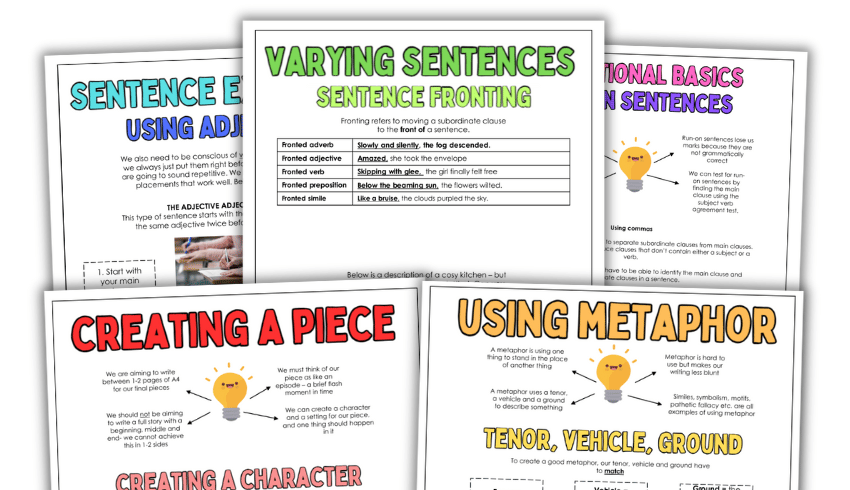

Practical guide to creative writing

This free 33-page GCSE English creative writing booklet will help secondary students develop their skills by focusing on the technical and stylistic aspects of fiction writing.

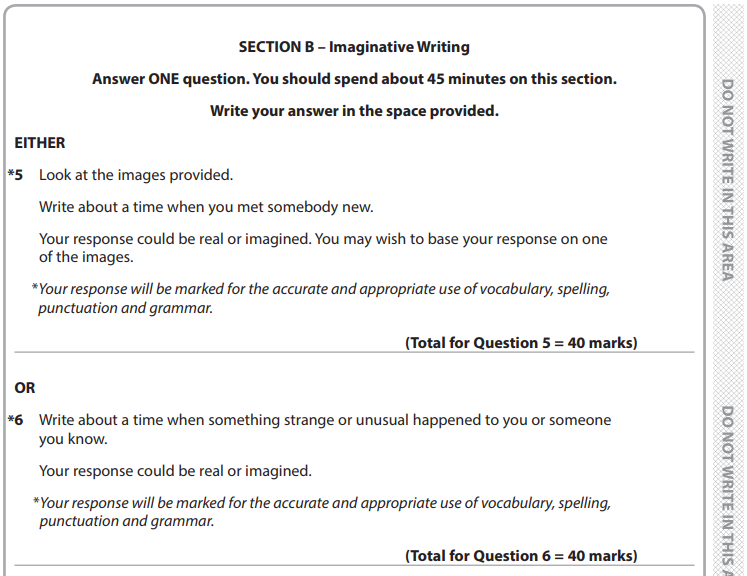

Past papers for GCSE English Language revision

Just as we included them in our roundup of GCSE English literature revision resources it makes sense to start with past papers.

Whichever exam board your school uses, you’ll find old papers at Revision World.

Paper 2 Question 3 practice

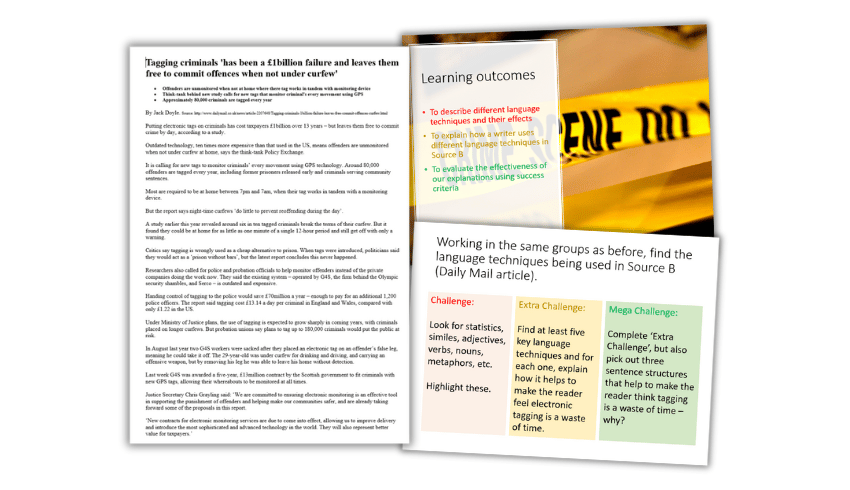

This fully resourced and differentiated lesson helps students to approach AQA English Language Paper 2 Question 3, which focuses on language analysis. The download contains a one-page article and accompanying PowerPoint.

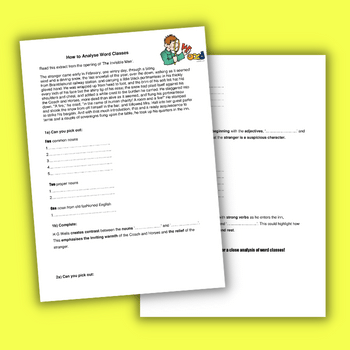

GCSE English Language revision worksheet

This two-page worksheet activity will encourage your GCSE pupils to focus on close analysis at word level.

First you need to read an extract from The Invisible Man by HG Wells, before picking out certain word classes. Then you fill in some incomplete sentences, analysing the author’s language choices.

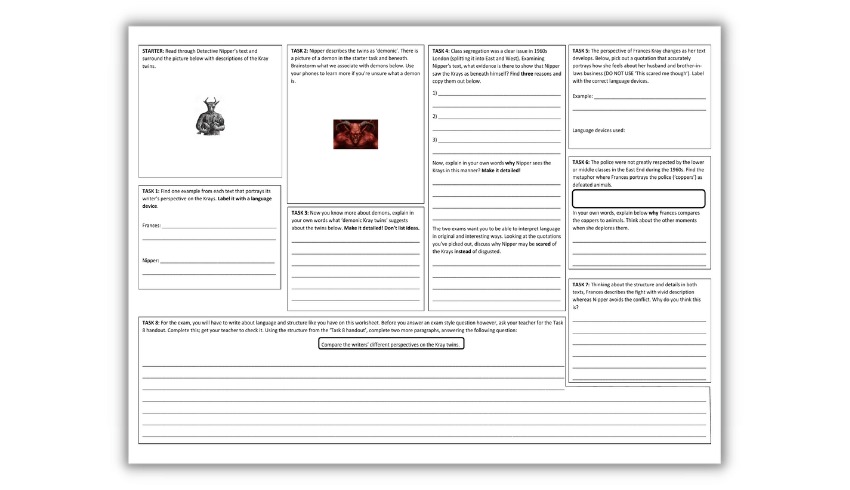

Kray twins lessons

Use this Kray twins Powerpoint, two reading extracts, worksheet and example answer to explore and practise skills for both Paper 1 and Paper 2. There’s enough materials here for three lessons.

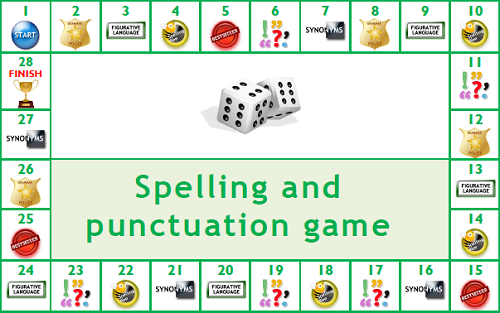

Key terminology recap

This bundle of resources from TeachIt helps students recap key words and terminology for GCSE English Language. Go over important skills for the exam by playing some tried-and-tested games and activities, like this printable language board game.

Revision tool archive

At getrevising.co.uk you can filter through the hefty bank of resources and narrow it down by level, subject, examining body and curriculum area. This means you can get exactly what your class needs.

Study guide

Here’s a handy 17-page PDF guide that takes you through each of the questions on both papers.

Geoff Barton resources

This page from Geoff Barton contains various resources for GCSE English that he has put together from his own teaching over the years. The revision archive includes Handy Revision Hints, ‘Interestingness’ and more.

Online GCSE English Language revision tips

This concise and well-presented revision guide should be well suited to young people’s tastes.

BBC Bitesize

One of the many benefits of the BBC Bitesize site is how well it is laid out. It’s so easy to find everything you need. And you know that it will all be formatted in a way that’s, as the site name suggests, easily digestible.

One of the other benefits is the the wealth of high-quality videos. These can be a great means of digesting information rather than students trying to cram in every note they’ve made, work they’ve done and handout you’ve created over the last year.

So, this video, for example, and its accompanying guide, takes pupils through the influence of poetry and rhyme on modern rap music.

Englishbiz

This set of skills-focused resources lets pupils test their skills at analysing poems, pieces of writing and more. They can also create their own piece.

Getting students to revise

English teacher and author Chris Curtis explains how to get your English students past the old ‘I can already read and write’ fallacy when the time comes for them to revise…

English can be a problematic subject to revise because it is so rich. The most highly motivated and driven students will attend revision sessions, complete practice papers and succeed. However, students in the middle can be very ‘middling’ in their attitude towards revision.

They are the students who, with just a few small changes, could make huge strides in their progress, if only we could get them to revise.

Booklets

What should students revise? How should they revise? These were the two questions we asked ourselves when addressing revision.

Having decided that practice and spaced practice were more important than copious notes, we produced a termly booklet of tasks that made the students practise a skill, or directed students to revise a particular aspect.

“We produced a termly booklet of tasks that made the students practise a skill”

Its contents related to the forthcoming mock exams and consisted of the following (5 of each):

- Romeo and Juliet exam questions

- A Christmas Carol exam questions

- Pages for collecting key quotations

- Tasks related to the reading section of GCSE English Language Paper 1

- Photographs for planning Question 5 on Paper 1

- Sentence structures to copy, imitate and practice

- Banks of words to learn and practise in a sentence

- Mind maps to create

- Spaces for making notes from viewed YouTube videos

- Spaces for the pupils’ own revision notes

We distributed the booklet towards the start of the term, and we didn’t give out any other homework. We explained to students that this booklet was designed to help build good habits in terms of revision and promote the strategy of ‘A little, often’.

On the front of each booklet was a grid, and for each task they completed they ticked off a square. We tracked their work across the term and monitored their progress towards achieving the goal of completing all 50 tasks by the end of the term.

The tasks themselves were largely short activities that didn’t involve the student having to write lengthy pieces or marking on the part of teachers.

We were looking for evidence that the students had engaged with the tasks, rather than producing the swathes of copied-out notes and highlighting that are often a poor proxy of revision.

“We were looking for evidence that the students had engaged with the tasks”

This approach transformed our approach to setting homework and monitoring engagement in the subject. It was particularly helpful for our weakest students, providing a supported, structured approach to revision that generated some excellent results.

Place the emphasis on students

We also changed the way we structured our curriculum.

Previously, in the run-up to the exams we would dedicate entire lessons to specific set texts or elements of the paper. We would break down the lesson schedule and produce a formula to cover what we felt was important:

‘Right, we have ten lessons left – so that’s three lessons for Macbeth, four for A Christmas Carol and two for the language papers…’

We abandoned this approach completely, in favour of placing the emphasis on students from an early stage.

Teachers are naturally kind, and in our kindness we’ll give students safety blankets. It used to be that if they didn’t revise, they would have at least had these last few lessons to help plug the gaps.

From the start of Y10, we made it clear that there was to be no more plugging of gaps or quick solutions. All students were given a cheap copy of the texts. They were responsible for making annotations in their books and keeping them safe.

“We made it clear that there was to be no more plugging of gaps or quick solutions”

We opted to now focus on the importance of all lessons, since there wouldn’t be another lesson going over the same things again at a later date. If they didn’t take in the material during this lesson, they’d just have to do more work later.

Things also changed in Year 11. Lessons now start with regular questions on all the texts, which serve to highlight gaps and areas for the students to work on – ‘Tom, you need to work on Macbeth; Jasmine, you need to work on your poetry.’

We were working to highlight gaps and direct students towards what they should focus on.

Keep parents in the loop

Do parents know what their children’s revision looks like? Schools throw the word ‘revision’ around with aplomb, but don’t spell out what revision should be and what it should look like to those people best placed to see it in action.

We therefore started regularly emailing parents about revision, beginning with a short email spelling out what students should be revising at that point and what they had been given to help them.

Later, I’d email parents telling them about the mock after the holiday, what it was on and where they could find some supporting resources.

This soon became a regular thing, and made sure that the same messages got home.

It also helped to ensure that some students weren’t pulling the wool over their parents’ eyes. I did have one student tell his mother that ‘revision homework was optional.’ Parents want to help their child, but we need to communicate what things should look like in practice.

“I did have one student tell his mother that ‘revision homework was optional”

Homework and revision are two external factors that are largely out of our control. Turning revision into a public relations event has really helped us and our students.

We are now much clearer about our expectations and what, for us, revision looks like.

Changing attitudes to revision means having a clear vision of revision. All too often, we leave things to chance.

Chris Curtis is author of the book How to Teach English, published by Crown House Publishing. Visit his website at learningfrommymistakesenglish.blogspot.com.

- The date of each exam or mock

- The texts students should be revising or rereading at that time

- Where students can find resources

- What materials you have given students to help them revise

- What revision sessions are available for students

- Details of any revision guides you recommend

Run a ‘lecture-style’ intervention programme

When Rainham Mark Grammar School head of English Mark McDowell decided to implement mini revision lectures in his school, he had no idea how well they would be received…

At my school we decided to offer 12 bespoke lectures for students to attend every Thursday afternoon, from January onwards. They were unashamedly academic in tone.

Two lectures would run, for between 30 and 40 minutes – one for English Literature and one for English Language. They would drill into a facet of the exam paper or area of a text.

Trending

All attendees would leave with a concrete skill or piece of knowledge that they could take with them into the examination. For example:

- The Didactic Tone of Dickens: Exploring the Moral Messages of the Novel

- Develop your understanding of Dickens’ intentions in writing the novel. This will help with context and exploration of authorial intent.

- Apples and Oranges? Comparing Non-fiction Texts across the Centuries

Develop your ability to compare two non-fiction texts 100 plus years apart. This is ideal for Paper 2, Question 4.

Of course, these could be tailored to the context of any particular school.

Planning and preparation

Teacher workload was a key consideration. Six teachers would plan two lectures each; that was it.

I had a wealth of experience in my department (76 years of English teaching experience – including two GCSE examiners, which I was at pains to let the Year 11 cohort know!) and this felt like a logical way to utilise that experience effectively.

In a department meeting, we discussed the areas we felt students needed help with. This is what informed the titles and content of the lectures. Teachers would deliver each lecture twice.

That meant I had 12 weeks of high-quality additional provision planned that could accommodate 60+ students a week. I also gave over one hour of directed department time to the planning of these lectures.

“I had 12 weeks of high-quality additional provision planned that could accommodate 60+ students a week”

How better could I use that time than allowing my department to plan – in some cases collaboratively – a suite of lectures to enhance the subject knowledge and skills of our students? It certainly beat going over data.

The lecture schedule was printed out and given to all Year 11 students as well as being emailed to parents. Posters were put up around the department and I also pushed it at assembly.

Additionally, guidelines on lecture etiquette were typed up on the sheet. The students needed to know that rocking up with a bag of Doritos and an energy drink was not going to happen. They were to arrive on time, and behave accordingly.

A flying start

I waited with bated breath. Would they really come in January for revision? Well, yes, they would. It’s early days, but so far the programme seems to have been a real success.

“Would they really come in January for revision?”

We had a full house on the first session. So, a third of our cohort had an additional lecture on either the presentation of women in Macbeth or how to compare two non-fiction texts. I was over the moon.

I’ll hand over the last words to one of our students, Christopher Key (Y11):

“The English Lectures have been a very positive contribution to revision. It is clear from my position as a student that a lot of effort has been put into organising the timetable. The English department has managed to fit in two lectures a week and they will be repeated so you can go to both before the exam.

“The lectures have attracted all levels of ability in the year and even the ‘cool’ students are making an effort to go. What more could you wish for?”

I’ll take that.

More GCSE English revision techniques

English advisor Zoe Enser sets out the practices and strategies that will see your students triumph on exam day…

I’m always quick to move students away from busy and inefficient revision practices, like reading over the text, or using heavy streaks of highlighting without consideration of what said highlighting is for.

Instead, I use regular, short sessions to complete the below activities:

Revision clocks

This involves giving students an outline of a clock, divided into 12 blank segments (A3 size works well). They then add information to the segments, taking five minutes to complete each one (out of the 60 minutes represented by the clock).

This breaks their revision down into manageable chunks.

This activity can work well in any subject, though for English I’ll get the students to complete revision clocks based on key themes, concepts and characters.

It’s important to not cover too wide a topic, or else the completed segments can end up being rather superficial.

I’ll get them to practise doing this in class after modelling the process, so that they can see how it works. I’ll insist that they spend their full allocation of time really thinking hard about the concept, rather than moving on to another topic too quickly.

This is done ‘closed book’, so that they’re encouraged to retrieve as much as possible. Since they’re the ones selecting the information they want to include, they’re drawing on a generative learning process.

Having spent time focusing on the concept, we’ll then look at an exemplar, perhaps developed as part of the learning process, and note where the gaps are.

Flash cards

Similarly useful across a range of different subjects, these are especially handy for internalising bodies of knowledge and key English terminology.

Writing flashcards for specific texts that contain key quotes relating to, say, certain themes and ideas can be a powerful revision process in itself.

You can then couple this with the principles of spaced or distributed practice, getting students to organise the cards into different piles they can return to on different days.

If you can ensure that the information on the cards is indeed stored, you’ll have the makings of something really powerful.

Remember that it’s important for students to see where they’re struggling and where their knowledge gaps are. Allow them to decide which chapters in a text to return to, or what vocabulary they may need to revisit.

“Remember that it’s important for students to see where they’re struggling and where their knowledge gaps are”

Cornell notes

This note-taking system can be a really useful way of helping students organise their revision notes, while also providing them with opportunities to self-test.

It can work particularly well when reading through chapters of a text, watching a Shakespeare play or listening to a lecture.

Students simply divide a page into three sections – notes in a larger main section, key questions or revision topics down one side and an optional space at the bottom for summing up.

The main notes might comprise bullet points, sentences, diagrams and maps or some other generative activity that’s reliant on selecting, organising and integrating information into their schema.

The space at the bottom is there to provide a quick summary that students can use to review key topic information.

If, for example, students were to produce a page of Cornell notes for each poem in a series, chapter of a book or character in a play, they would eventually have their very own home-grown revision booklet, complete with quiz questions at the side of every page for ‘check and answer’ purposes.

Doing this will also let teachers quickly check if there are any misconceptions.

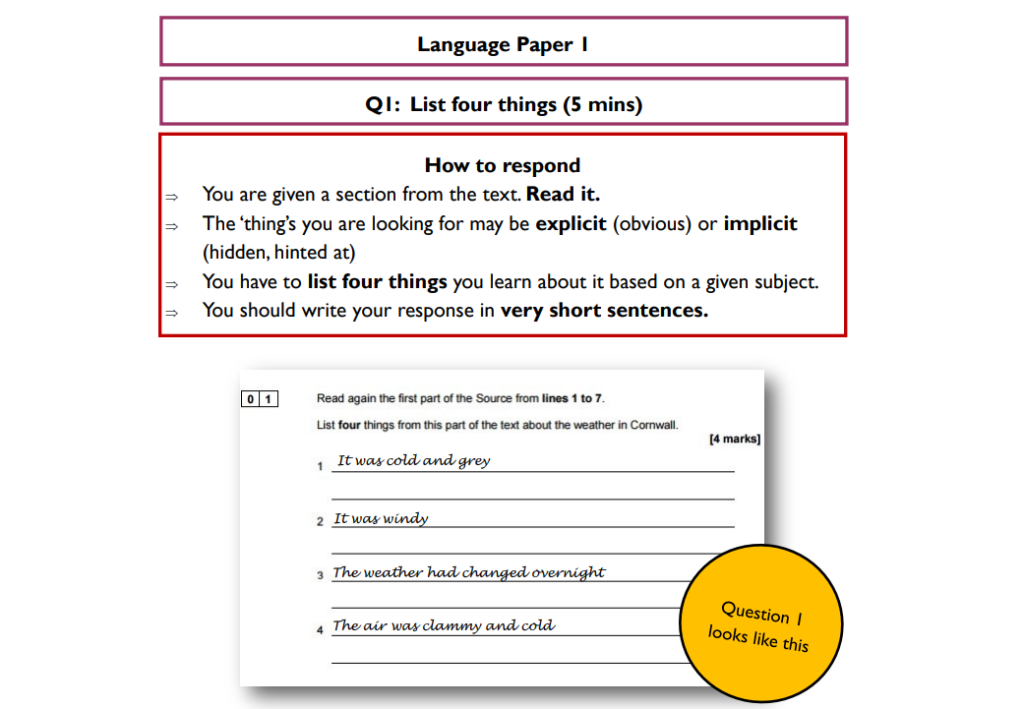

English Language tips

The above revision techniques are easy to apply to literature topics, where there’s a clear body of knowledge to accompany each text, but they can seem less practical for the largely unseen texts and tasks of English language study.

However, language still involves learning specific vocabulary – the structural or rhetorical devices specific to non-fiction texts, for example.

There are also processes when approaching language questions that are quite distinct from essay-style literature responses, which students need to be familiar with.

Self-testing techniques are still very much relevant when it comes to achieving the fluency and agility demanded by language papers in the exam room.

Students should get used to completing deliberate practise tasks for both language and literature topics. They should take the opportunity to read and annotate, plan their responses and answer longer questions as part of their revision.

“Students should get used to completing deliberate practise tasks for both language and literature topics”

It can be useful to turn these into distinct homework tasks and encourage the systematic approaches above, so that they’re able to focus on knowledge and retrieval. This will help them considerably when they come to attempt those longer exam responses that are designed bring their knowledge together.

Whatever they end up doing, your students need to be making sure that information is being retrieved, reconsidered and then stored all over again.

The more they do this, the more they’ll ultimately retain. The more intricate their schema, the more the new information will adhere to the old.

Metacognition

More importantly, good revision relies on elements of metacognition. Students need to be aware of what they have available to them in relation to a text and the knowledge they possess.

They then need to be clear where they may have gaps, and ensure they have the materials – be it lesson notes or revision materials you’ve provided – they need to restudy.

Above all, they must be clear that they’ll need to test themselves repeatedly to ensure this information remains available to them when they need it. Not just tomorrow, or next week, but during the mock, the actual exam in summer and any time after that.

This calls for a careful and systematic approach, and will involve hard work. There are no shortcuts.

“There are no shortcuts”

It doesn’t matter if their revision materials look pretty (unless that makes it more likely that they’ll actually use them). But they will need to be focused, designed for regular practice and able to get the relevant information stored in their heads for life.

Zoe Enser is a specialist advisor for English at The Education People. Download our free Macbeth essay two-lesson resource pack.