Reading comprehension KS2 – Ultimate resource guide for Years 3-6

Make sure your pupils have all the reading comprehension skills they need with these worksheets, lessons, activities and more…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Unlock the potential of young minds with our ultimate reading comprehension guide, featuring the best worksheets and resources tailored for Years 3, 4, 5, and 6.

(If you teach Year 1 or Year 2, check out our round-up of the best KS1 reading comprehension resources. If you teach KS3, we’ve also got worksheet packs for Year 7 and Year 8.)

KS2 reading comprehension resources

Non-fiction and fiction worksheets

These engaging, free comprehension worksheets for Y1-6 cover fiction and non-fiction. Each high-quality comprehension text is followed by eight pages of questions.

Real Comprehension curriculum programme for Years 1-6

Real Comprehension is a unique, whole-school reading comprehension programme from Plazoom, designed to develop sophisticated skills of inference and retrieval. It builds rich vocabularies and encourages the identification of themes and comparison between texts from Years 1 to 6.

Access 54 original fiction, non-fiction and poetry texts by published children’s authors – all age appropriate, thematically linked, and fully annotated for ease of teaching.

Free Beano comprehension worksheets

This free comic book comprehension resource is great for reluctant readers and more fluent pupils alike, helping children become familiar with narrative structures.

It includes three Beano comic strips, three reading comprehension question worksheets, comic puzzles for working on narrative sequences and a blank comic template.

Reading comprehension worksheets

No matter what book you’re reading in class, use these free worksheets from Oxford University Press to track what’s happening in the plot, new words you come across and characters’ emotions, attributes and relationships.

Classic texts KS2 reading comprehension packs

These reading challenge mats from literacy resources website Plazoom provide a quick burst of comprehension practice, ideal for morning work, a short reading session or even sparking an interest in a classic text.

Each mat contains a brief extract from a classic text. There’s a range of reading challenge questions focusing on the key reading skills of inference, information retrieval and the use of language.

- Pack 1: The Invisible Man, A Christmas Carol, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

- Pack 2: Kidnapped, Oliver Twist, The Time Machine

- Pack 3: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Dracula, The Hound of the Baskervilles

- Pack 4: 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Gulliver’s Travels, Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe

- Pack 5: The Jungle Book, The Railway Children, Doctor Doolittle

- Pack 6: The Wizard of Oz, Five Children and It, The Wind in the Willows

- Pack 7: Treasure Island, Great Expectations, The War of the Worlds

National Literacy Trust resources

If you’re looking to brush up on your knowledge of reading comprehension strategies, these four free handouts from the National Literacy Trust will prove useful. They cover discussion exercises to try with KS2, different definitions of reading comprehension, a further reading guide and a breakdown of national curriculum reading comprehension objectives.

KS2 fiction and non-fiction question cards

These comprehension cards from Plazoom give example questions to develop a range of comprehension skills when reading fiction and non-fiction texts. This includes:

- understanding vocabulary

- retrieving information

- sequencing events

- making inferences based on what is said and done

- predicting what might happen next

- encouraging positive discussions

Use them in one-to-one reading sessions, group guided or whole class reading sessions. Click here for the fiction cards and here for the non-fiction cards.

Year 3 and Year 4 reading comprehension

Year 3 Marie Curie reading comprehension

This free Year 3 reading comprehension resource includes a Marie Curie fact file from Whizz Pop Bang magazine, plus two question sheets, one for lower-ability pupils and one for higher-ability pupils.

Reading comprehension non-fiction texts

These free Year 4 comprehension worksheets are all about the structure of non-fiction texts. There’s a short text for pupils to read, all about outer space, plus activities to complete.

Reading comprehension fiction worksheets

Each of these Unlocking Inference units from literacy resources website Plazoom focus on a different story, and are designed to support you in your teaching of inference and vocabulary.

They feature extracts which have been annotated with running questions to help you check that children are creating accurate images in their minds, and to clarify their literal understanding (including of key vocabulary) – an essential step towards them making reasoned inferences as they read.

The resources focus on famous stories, including Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Peter Pan.

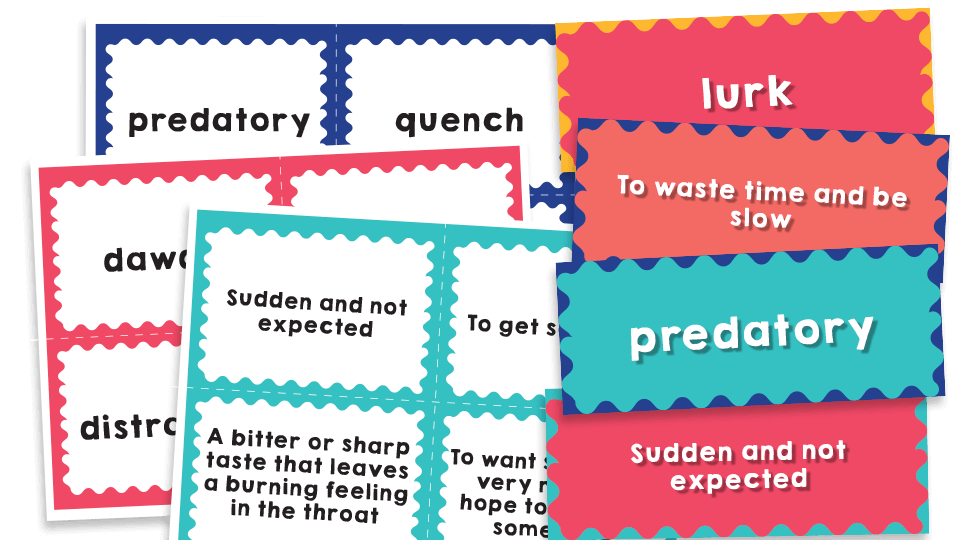

Tier 2 reading comprehension worksheets and vocabulary cards

Tier 2 words are ones which children might encounter in text but are less likely to use in everyday conversation. As these words are often unfamiliar to children, they can sometimes act as a barrier to reading.

Choose from a Year 3 pack and a Year 4 pack, both from literacy resources website Plazoom.

Tier 2 words can be used by children to add more adventurous or formal vocabulary to their writing. The download includes word cards, definition cards, worksheets and answer sheets.

Non-fiction reading comprehension worksheets pack

These packs from literacy resources website Plazoom focus on famous figures in history, Florence Nightingale and Marco Polo.

Each one builds children’s skills of recall and inference, and enhances their vocabulary, and includes a factsheet to work through, as well as an answer sheet.

Find Marco Polo here and Florence Nightingale here.

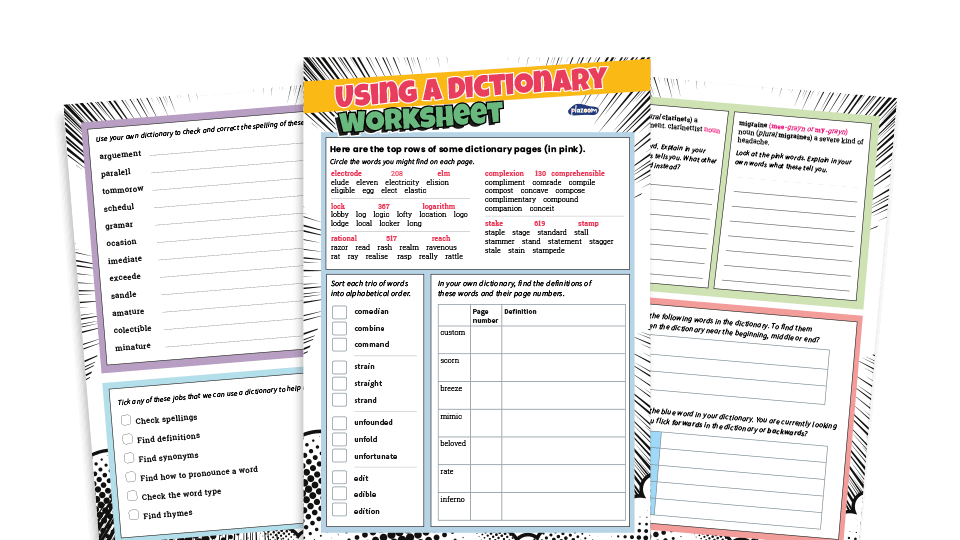

Y3/4 dictionary worksheets

These KS2 dictionary worksheets for Year 3 and 4 from Plazoom support children in learning to use dictionaries to check the meaning of words that they have read; a LKS2 curriculum aim for reading comprehension.

Activities include sorting trios of words into alphabetical order, finding the definitions of words and their page numbers and using your own dictionary to check and correct the spelling of words.

Year 5 and Year 6 reading comprehension

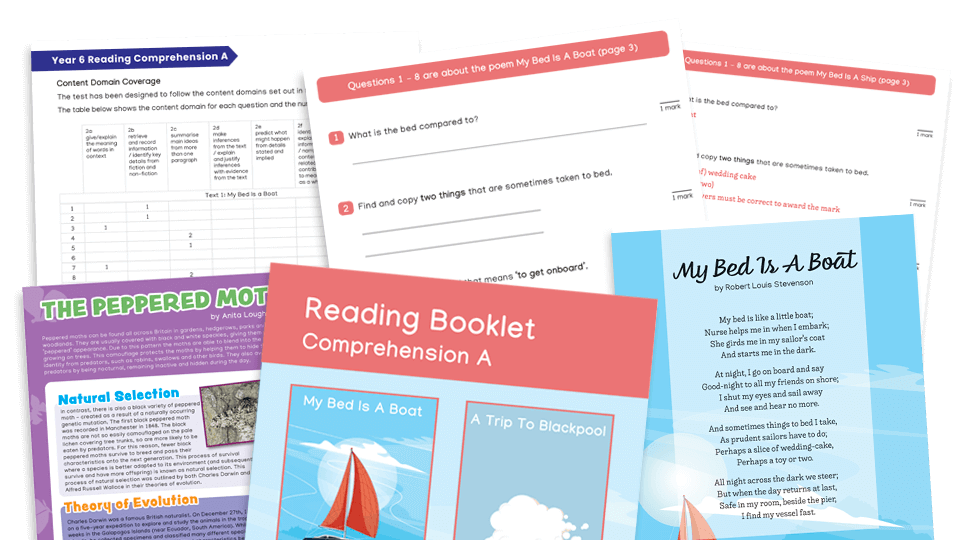

KS2 SATs reading assessment practice pack

Get your Year 6 pupils ready for the SAT reading comprehension test with this free reading comprehension pack. There are three texts in the reading booklet: a classic poem, a non-chronological report and a narrative.

Questions have been mapped against the content domains so that you can identify question types and reading curriculum areas that your pupils may need to revisit.

Tier 2 reading comprehension worksheets and vocabulary cards

These resource packs from literacy resources website Plazoom features 48 Tier 2 words for Year 5, and another 48 for Year 6. Challenge children to add more adventurous or formal vocabulary to their writing and use the included worksheets as a reading comprehension activity.

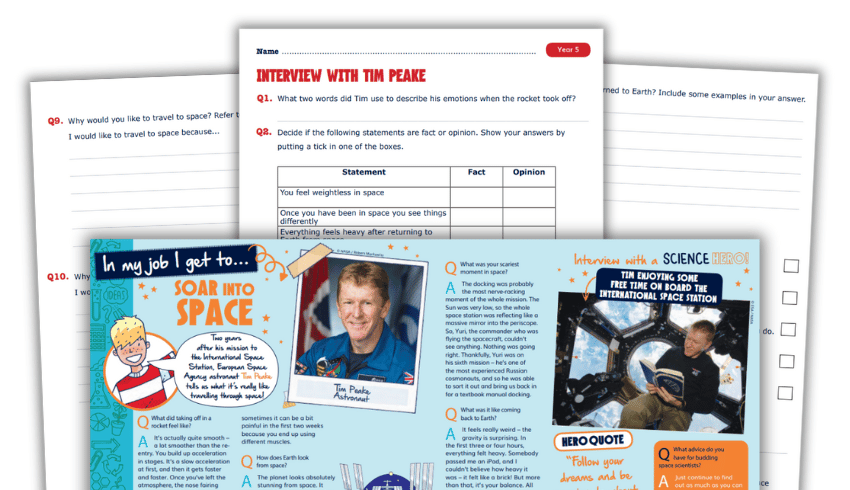

Astronaut interview & differentiated worksheets

This free Year 5 comprehension resource contains an interview with European Space Agency astronaut Tim Peake plus differentiated worksheets for higher- and lower-ability students.

UKS2 reading comprehension worksheets

As above for the Year 3 and 4 versions, these Unlocking Inference units from literacy resources website Plazoom have been designed to support you in your teaching of inference and vocabulary. They’re based on a carefully scaffolded whole-class reading approach, including multiple iterations. This enables all pupils to access even relatively challenging texts.

Each one is based on an extract from a famous story, including Little Women, The Secret Garden and Treasure Island.

UKS2 ‘Jabberwocky’ poetry resources pack

This poetry pack from literacy resources website Plazoom is based around the classic nonsense poem ‘Jabberwocky’ by Lewis Carol. It contains lesson ideas that could be completed over a series of five sessions for Year 5 and Year 6, covering comprehension, vocabulary and composition.

Reading comprehension teaching advice from experts

How I boosted comprehension with song lyrics

Sing your way through SATs with Matt Dix’s guide to using popular music to increase children’s literacy skills…

As a Year 6 teacher, I’ve been thinking long and hard about reading, particularly since the SATS tests have become increasingly more difficult, but also because I want to get better at teaching reading itself. Above all, I want my class to read with greater understanding, to use key reading skills and to persevere through tough texts.

Two things have particularly resonated with me during this period. The first was this blog post by teacher Aidan Severs. I was intrigued by the idea of allowing children to retrieve and record information and look for context clues before the inference itself can really take place.

And secondly, I’ve also been inspired lately to give the guided reading carousel the boot and opt instead for whole-class reading.

Whole-class reading

There’s been much research of late describing the benefits of mixed-ability teaching, as well as whole-class reading. One thing has always annoyed me when collating reading resources, though, is the dreaded reading comprehension!

Much like how an independent writing task doesn’t improve writing, neither does an independent reading comprehension task. This is why more and more practitioners are focusing on key skills in a more organised fashion.

Take Rob Smith’s memorable mnemonic, VIPERS (Vocabulary, Infer, Predict, Explain, Retrieve and Summarise), or Rhoda Wilson’s DERIC (Decode, Explain, Retrieve, Interpret, Choice).

So, with all of this in mind, where exactly did it all take me?

Using lyrics in inference lessons

Well, as a teacher with a huge passion for music of all genres and ages, it occurred to me that the lyrics to many famous songs work as both narratives and poems. I carefully chose ten famous songs and broke each one into four separate reading comprehensions:

- Retrieval and Recording

- Context Clues

- Inference

- Independent Assessment

First, we read the words and annotate them; then listen to the song, learn and sing a chorus or two; and then crack on with the comprehension.

During an inference lesson about the Tom Waits song ‘What’s He Building?’, I had one child using a range of clues to explain how there could be a murderer in the house, while the other child used identical clues to suggest that it was an elf building toys for Santa!

If anything, the lyrics provided an enlightening respite from the mundanity of SATs papers!

All in all, it allowed children to fully engage with a complex song, analyse its contents and then practise key skills either as a whole class, with a mixed-ability partner, or answer some questions independently. They then had the opportunity to answer an assessment of mixed questions on the last day.

Rather like Maths No Problem, I’m now modelling answers, completing guided questions and then allowing them to complete some questions independently.

All of this is done at snail’s pace, over the course of one week, with one song. This allows for discussion, critical thinking and the constant revisiting of reading strategies.

During the assessment, children also have to circle the correct code which links to a certain reading skill, and then learn the following strategies for each skill, which I have on display if need be.

1 | RR (Retrieval and Recording)

- Skimming

- Scanning

- Underlining key words

- Knowing synonyms of words you are looking for

- Knowing antonyms of words you are looking for

- Copying the word/sentence/phrase accurately

2 | CC (Context Clues)

- Replace the unknown word with a replacement which works

- Look at the rootword for clues

- Identify any prefixes or suffixes

- Knowing synonyms of words you are looking for

- Knowing antonyms of words you are looking for

- Identify articles and other words to give to a clue about the word class

3 | INF (Inference)

- Think what you already know about this subject

- Use two or more clues in the text to come up with a new piece of information

- Consider summarising paragraphs to aid general understanding

- Consider a change of thinking

4 | S (Summary)

- What inferences can I make?

- What is the overall ‘feel’ of the piece?

- Summarise a verse/paragraph in a word or short phrase

- Be general rather than specific

By practising a new skill for 30 minutes each day, I can model answers, use suitable vocabulary for inferences (this emphasises…, this suggests…, assumes…, most likely… etc) and transfer these skills into those mixed-skill reading comprehensions which means children flick from one skill to another without the faintest idea they are doing so.

When our SATs results came in, and with a more-challenging set of cohort data than the previous year, we ended up increasing the number of children making the expected standard by 12%. It may simply be down to 30 minutes of reading every day, but the focus on these key skills can only have helped.

Plus, if you can get your class listening to Iron Maiden, Tom Waits and David Bowie in the space of a few weeks, something’s going well!

Matt Dix is a Year 6 teacher and one-third of Manic Street Teachers, a musical trio that create literacy, maths and science songs and accompanying resources.

How I used Adele’s ‘Hello’ for comprehension

Need to improve comprehension? Then draft in Adele as your TA for the day, says Shareen Mayers…

I was recently given the challenge of improving reading comprehension skills in a school where results were particularly low. I knew I’d need to come up with something creative if I wanted the children to be excited and engaged – but when I first presented pop songs to both the Y6 classes, I’m fairly sure the pupils were confused…

Fortunately, it didn’t take long for the idea to catch on, and reading began to dramatically improve as a result. Indeed, the children soon became keen to show off their new comprehension skills.

You can use the activities I devised for guided/group reading and/or whole-class sessions. If you’d like to try them out with your own class, here’s my quick guide to how you can use pop music to stimulate discussion and add a little fun to reading comprehension lessons…

Getting started

First things first, you need to choose a song to play to the children (a fairly clean one!). My song of choice is Paul Damixie’s remix of Adele’s ‘Hello’, because it has a fast beat and almost certainly makes the class want to dance along.

Hello, can you hear me?

I’m in California dreaming

About who we used to be

When we were younger and free

I’ve forgotten how it felt

Before the world fell at our feet

There’s such a difference between us

And a million miles

After this, you can ask a range of questions to enable pupils to practise their comprehension skills. Bearing in mind that the bold question stems can be adapted for any other songs, these could include:

- According to the text, where is Adele dreaming?

- How many miles apart are they?

- Find and copy one word that means you cannot remember something.

- What is the main message in this section?

Some pupils might even discover that Adele is not actually in California. Despite what a first listen to the lyrics might suggest, the song is not even intended to be about an ex-boyfriend. Adele is actually talking about reconnecting with herself, as she explains in the tweet below:

Deepening oral responses

To really develop pupils’ reading comprehension skills, I like to scaffold their responses so that they’re able to give extended answers to key questions. A simple way of doing this is to use a three-step approach:

- ‘I think that…’ (views)

- ‘Because…’ (evidence from the text)

- ‘This shows/demonstrates…’ (explanation)

Hello, it’s me

I was wondering if after

All these years you’d like to meet

To go over everything

They say time’s supposed to heal ya

But I ain’t done much healing

(At this point the grammar police will be unhappy about the non-Standard English, but this is a good teaching point as it adds to the effect of the song).

I have encouraged pupils to write their answers in standard English, which is a great way of embedding grammar skills.

Key question: Explain why Adele is unhappy using evidence from the text

- I think that she is unhappy

- Because she says she has not done much healing

- This shows that she hasn’t got over whatever upset her

Modelling how to answer these questions is very powerful, because it will ensure pupils are using the text to answer questions, and encourage them to explain and justify their answers.

It is important to note that pupils should not repeat their point in their answers. For example:

- I think that she is unhappy

- Because she says she has not done much healing

- This shows she is unhappy

Encouarge pupils to explain point one, use evidence from the text to justify this and explain what this means.

Apply to a reading comprehension text

Once pupils have practised this orally and are confident with applying this technique to a range of pop songs, film clips or pictures, these skills can be applied to a reading comprehension text. Teachers will therefore be developing pupils’ comprehension skills first, before carrying out written comprehension questions.

Shareen Mayers is an experienced primary school teacher.

The best questions to ask to support children’s reading comprehension

Ascertaining children’s understanding of a text shouldn’t feel like pulling teeth, nor should it require it. Just get creative with effective questioning, say Nikki Gamble and Camilla Garafolo…

It’s hard to imagine a reading lesson where you wouldn’t ask questions to find out what children understand about a text. But since the 1970s, research has shown that asking too many questions without giving the reader time to formulate their own questions or process their thinking can inhibit, rather than support, comprehension.

There are, however, steps you can take to make sure your questioning is effective. You can help children formulate their own questions and give them opportunities to pursue the answers.

You can use your questions to respond to pupils’ ideas – to structure and scaffold their thinking so that they come to a deeper understanding of the text. And you can ask appropriate questions before, during and after reading, which develops comprehension more effectively than only asking questions afterwards.

In Richmond, teachers have been taking part in the Developing Excellence in Reading project and reviewing how questions and alternative prompts are used in their classrooms.

What follows are three of the strategies that have proved particularly effective when it comes to improving reading comprehension.

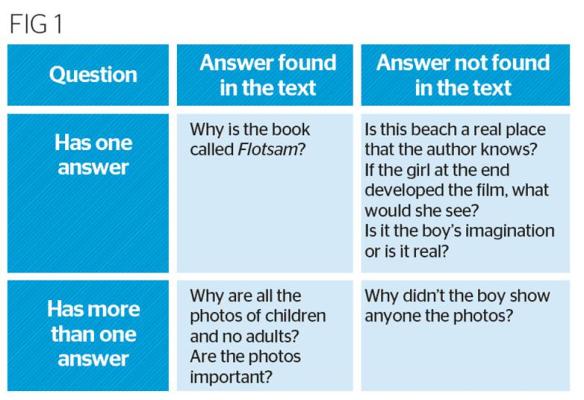

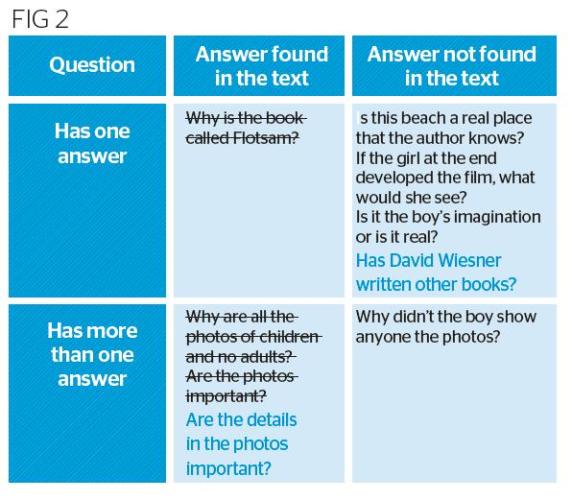

1 | Use question organisers

These help children analyse their own questions. For example, the question quadrant below illustrates how a group of Year 5 children organised their thoughts after reading David Wiesner’s wordless picture book, Flotsam.

Following a first read-through, they wrote questions about the things that interested or puzzled them and then mapped them onto the grid. (For younger classes, the quadrant may be too complicated. If so, simply use a ‘question organiser’ with two columns – ‘Questions that have one answer’ and ‘Questions that have more than one answer’.)

Initially, the teacher modelled the process, helping the children decide where their questions should be placed and then they completed the task independently in groups.

Working document

When they had finished, the teacher reflected with them. How easy was it to place the questions? Were some more difficult than others? Why?

When the children returned to the text for a second reading, there were ‘pennydrop’ moments as they found answers to their own questions.

At the end of the session, the teacher asked the group to cross through any questions they had been able to answer.

She also asked them whether any new questions had emerged. She wrote these on the grid using a different colour to distinguish them from the first set.

The quadrant had become a useful working document charting the progress of the pupils’ thinking.

Simpler version

One year 4 teacher thought the Question Quadrant was too complex for her class and came up with a solution to simplify the process. She decided to use one large question organiser for the whole class, which she divided into two columns.

The pupils wrote questions on post-it notes and placed these on the organiser. As they read further, they returned to it and removed the questions that they had answered. As the class read further, they added new questions as they arose.

Once your class has filled out a question quadrant or organiser, reflect on which questions will be easiest to answer. See if any question has potential for framing a subsequent guided reading session, or could be pursued as a homework task.

2 | Have a Quescussion

Encourage pupils to question as they read by having a discussion entirely conducted through questions. This technique is called a ‘Quescussion’. Paul Bidwell at the University of Saskatchewan developed this idea.

Quescussions are usually short, around two to five minutes, and involve the class calling out questions, and only questions. It allows many students to make brief contributions without interventions from the teacher.

The rules

You just set out the subject (or in this case, text) to explore, and let them raise any questions that will help them to analyse and gain a deeper understanding of the topic. There are only a few simple rules, so pupils quickly get the idea:

- The discussion can only contain questions (they can be asked without the need to raise hands)

- A pupil who asks a question must wait until at least four other questions have been asked before asking another

- The teacher may stop the Quescussion to help the pupils think about the type of questions they are asking. They may be encouraged to ask more open-ended questions eg Why? How?

- If a statement is made instead of a question the whole class will shout STATEMENT! (Rhetorical questions that are thinly-veiled statements should also be policed by the class.)

Benefits

One of the benefits is that pupils who may be reluctant to talk feel more comfortable to volunteer a question as they are not in the spotlight.

Quescussions encourage more experimental and creative thinking because they are tentative. The teacher takes on the role of scribe to record the questions. These can then be grouped and organised and presented back to the class for future discussion.

Example

Here’s an example taken from a Year 6 Quescussion about a passage from The Secret Garden. The Quescussion provided an opportunity for the class to ask many questions that are central to understanding the behaviour of character Mary Lennox.

Passage

Mary had liked to look at her mother from a distance and she had thought her very pretty, but as she knew very little of her she could scarcely have been expected to love her or to miss her very much when she was gone.

She did not miss her at all, in fact, and as she was a self-absorbed child she gave her entire thought to herself as she had always done. If she had been older she would no doubt have been very anxious at being left alone in the world, but she was very young, and as she had always been taken care of, she supposed she always would be.

What she thought was that she would like to know if she was going to nice people, who would be polite to her and give her her own way as her Ayah and the other native servants had done?’

Quescussion

- ‘Who is Mary?’

- ‘Where has her mother gone?’

- ‘Has her mother died?’

- ‘Where is her father?’

- ‘How old is Mary?’

- ‘It says she was very young…’ ‘STATEMENT!’

- ‘How young is very young?’

- ‘Why doesn’t she miss her mother?’

- ‘Why is she all alone in the world?’

- ‘Doesn’t she have and brothers or sisters?’

- ‘Does she have any friends?’

- ‘Why is she self-absorbed?’

- ‘What does self-absorbed mean?’

- ‘Why does she only see her mother from a distance?’

- ‘Why is she going away?’

- ‘Where does Mary live?’

- ‘What is an Ayah?’

- ‘Where is this story set?’

- ‘I think it’s set in India’ ‘STATEMENT’

- ‘Is it set in India?’

Have a go by selecting a short text, poem, passage or photograph and organise a Quescussion. Record the questions, then group them into themes, display them, and return to them later – after you have read further.

3 | Make a statement

Asking direct questions isn’t the only way to encourage pupil questioning. Making a statement, especially a declarative one, can often reinvigorate a discussion. Initially, you may need to explain to pupils that statements are an invitation for discussion and are not irrefutable.

When you pose a statement, questions will naturally arise in the discussion that follows. Unlike with questions, where you look for the ‘right’ answer, with declaratives pupils start to question what the statement means, and try to find evidence to either prove or disprove it.

Examples

This is especially the case when you present strong statements, which allow for differing points of view and contention. Here are some examples:

- Memorial by Gary Crewe and Shaun Tan: ‘People’s memories are more important than memorials.’

- The Nightingale and the Rose by Oscar Wilde: ‘Oscar Wilde thinks education is more important than love.’

- Maggie Dooley by Charles Causley: ‘Maggie Dooley is lonely and unloved.’

- The Tunnel by Anthony Browne: ‘The boy is braver than the girl.’

Give groups a number of statements on strips of paper and ask the pupils to determine whether they agree or disagree with the statements, or whether they are undecided. When they have considered all possibilities, they should position the statements on a grid and provide evidence from the text to support their choice.

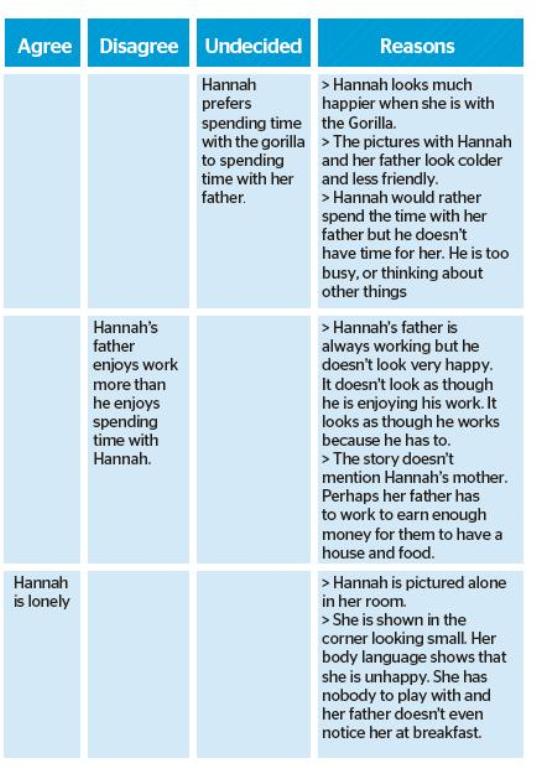

The table below is an example using statements about Anthony Browne’s Gorilla:

Sense of agency

At Barnes Primary School, using a range of strategies has noticeably developed the pupils’ sense of agency in their own learning. Discussions are more animated and purposeful.

One Year 4 child summed up the class’ thinking nicely: “Last year when we read a book, we would read it and then answer some questions set by the teacher. However, now that we get to ask our own questions, I think more about what the book has said and its meaning.”

Or, to use the words of another child, “I think it has helped me with my understanding, because now I stop when I finish a section of my reading, and check that I understand by asking myself questions.”

Nikki Gamble runs Just Imagine Story Centre. For further information about Developing Excellence in Teaching and Reading 7-14, contact nikki@justimaginestorycentre.

Teaching children who have excellent decoding skills but weak reading comprehension

If our weaker comprehenders neglect key strategies in the moment of reading, they won’t build basic meaning, says Tony Whatmuff…

Class 5W’s joke book is finally finished. It’s the first read-through and everyone has a copy. I scrutinise my four weaker comprehenders as they read the first joke: The worst job I ever had was drilling holes looking for water. It was well boring.

Not a facial muscle twitches. Nearby, however, hilarity erupts, then spreads throughout the class. My four weaker comprehenders look around bewildered.

I know these four children have a good sense of humour, and all of them can read any word I give them (triceratops, dodecahedron, etc), so what is happening? I’ll tell you. They’re reading in a totally different way to my splitting-their-sides children.

Breaking down the issue

In the moment of reading, these four are either neglecting key strategies or experiencing vocabulary and language difficulties. Here’s my best guess at what’s going on with each child…

Jacob: Jacob has OK vocabulary but fails to spot the important words and integrate them together to build meaning (worst job, looking for water, drilling holes, well, boring). He probably hasn’t made the connection between the first and second sentence either.

Unsurprisingly, as Jacob generally struggles to read with understanding, he reads little and may lack knowledge about the genre of joke reading.

Mala: Mala is still developing vocabulary and oral language as she’s only been in the UK three years. She probably fails to understand the dual meanings of key words, such as ‘well’ and ‘boring’.

Abe: Abe was born in the UK but comes from a language-deprived home and has similar vocabulary and oral language issues to Mala.

Mckenzie: Mckenzie has good oral language but is a passive reader who focuses on decoding and fluency rather than accessing his background knowledge about ‘drilling holes’, ‘well’ and ‘boring’, because he doesn’t know it’s important. The knowledge is there, but he’s not accessing it. This means he’s not activating inferences either.

In the moment of reading

These four children illustrate the multiple risk factors associated with weak reading comprehension, despite having excellent decoding skills.

For effective reading comprehension, children need the following:

- Automatic decoding, fluency and reading miles

- Good vocabulary and oral language

- Active strategies in the moment of reading

- Effective after-text strategies to answer questions

A problem in any one of these areas will result in a problem with reading comprehension. But it’s this ‘in the moment of reading’ idea I want to focus on.

Us adults in school are skilled readers, but the price we pay for our expertise is that the strategies we use have become hidden from us because we activate them so automatically.

For example, have you ever read late at night in bed when you’re feeling really tired, then realised when you reach the end of the page that you’ve taken a word in? In this scenario, you’ve been decoding the words but no key strategies in the moment of reading have been activated.

Effective reader strategies

So, what are the strategies effective readers use in the moment of reading? Effective readers:

- Use their background knowledge and make links with the text

- Predict or ask questions and then read on to ‘find out’

- Visualise and use inference

- Notice meaning breakdown and use repair strategies to understand

- Notice very important words, phrases and ideas and put these together to build basic meaning

Do we teach these strategies explicitly? Probably not. We’re all pretty good at asking children questions after reading a text to explore deeper meaning, but if our weaker comprehenders neglect key strategies in the moment of reading, they won’t build basic meaning as they read.

Asking them questions after a text is like trying to build a block of flats on top of a swamp.

Fortunately, it’s possible to model these ‘in the moment’ strategies to a whole class or group, using teacher ‘think aloud’ bubbles on top of text. Use your whiteboard to do this.

Modelling in this way is called ‘read aloud, think aloud’ and makes the elusive process of comprehension more concrete. Children can then practise these strategies on the same or a follow-on text, then share and discuss so that more meaning and enjoyment is gained from a text.

Tony Whatmuff is a trainer and author with 25 years of teaching experience. He is also a consultant on Oxford Reading Buddy, a digital reading service that develops comprehension by coaching and modelling key strategies. Find out more at global.oup.com.

How to explicitly teach reading strategies

Boost pupils’ post-pandemic skills by considering how you explicitly teach the strategies that children need to be successful…

Reading is the key to learning. However, if you’re a struggling reader, loving it can be a real challenge. Right now this is even more important, given that according to the DfE, pupils are on average two months behind in their reading learning as a result of the pandemic. For individual children, learning loss may be even greater, so how can we reverse this trend and ensure every child becomes a good reader?

The first step in improving children’s reading comprehension is to identify the exact level at which they’re reading. A diagnostic assessment and gap analysis will give you the information you need.

Try to get a snapshot of each child’s reading attainment, including decoding, fluency and comprehension, by using key reading skills.

Once your assessments are complete, look for patterns in your gap analysis and plan to address these through teaching and intervention.

Comprehension strategy – book choices

When teaching reading, choice of text is very important. Think about the complexity of decoding, vocabulary and content, and of course, engagement. Try not to just use familiar books, but instead focus on widening children’s reading repertoire by exposing them to different texts.

This is where your knowledge of children’s literature comes in. You could even explore paired texts, such as Beetle Boy and The Beetle Collector’s Handbook by MG Leonard so that children can make connections in their reading.

Cultural capital comprehension exercise

Pupils who struggle to read sometimes need to build their background knowledge and vocabulary. A child with good cultural capital will often have more of the prerequisite knowledge and skill needed to understand what they are reading than a disadvantaged child.

Try exploring key concepts and vocabulary before reading. For example, with Beetle Boy, you might discuss mystery stories, beetles, insects and museums first. Then you could teach children key vocabulary such as ‘specimen’ and ‘archaeologist’, giving them strategies to unpick unknown vocabulary.

With ‘archaeologist’, for instance, you could explain that ‘-ist’ means ‘somebody who does or makes’ and gather as many examples as you can which share this pattern, discussing their shared meaning.

Critical thinking and cognitive processes

Every good reader has a range of skills and strategies they use to make meaning. By explicitly teaching these, we can support all children to become resilient readers and give them the knowledge needed to comprehend any text they choose to read. But which skills and strategies need to be taught?

The most important skills of a reader are to retrieve information, define vocabulary in context and make inferences. A good reader will also sequence events, summarise content and predict what comes next. They will consider the effect of language, make comparisons and explore relationships.

These aspects of reading need to be taught progressively and regularly. Skills need to be explicitly taught and modelled, including the metacognitive processes we use when reading. For example, when teaching inference, you could introduce the idea of “‘What I read’ + ‘What I know’ + ‘What I think’ = my inference”.

By breaking down the cognitive processes behind reading, you can show children what a good reader does and give them the strategies they need to create meaning, before they practise and apply them using a range of texts, questions and activities.

Teaching reading skills and strategies is a complex process and can be daunting. Reflecting on your subject knowledge is really important and getting to grips with research such as the EEF Literacy Guidance Reports is a great start.

Reading journey

We know that reading for pleasure has a profound effect on children’s ability to understand what they read. We need to encourage a love of reading whenever we can. Children need daily time to read books they want to read. We need to immerse them in reading opportunities and show them reading role models.

By encouraging children to read for pleasure, we help them read more, and the more they read, the better readers they become. For all children to achieve their full potential, schools must consider their whole-school reading curriculum and whether it teaches the skills needed to decode, understand, and enjoy books.

Supporting a child on their reading journey is about so much more than just academic success. The benefits of reading go far beyond this. When we support every child to be a good reader, the benefits will stretch throughout their lives.

Jo Gray and Laura Lodge are authors of Schofield & Sims’ Complete Comprehension and education consultants for One Education. Follow Jo on Twitter at @jo_c_gray and Laura at @lauralodge208.

Turn your students into comprehension ninjas

Use Vocabulary Ninja Andrew Jennings’ ideas to help primary pupils effectively skim, scan and retrieve information…

1 | Effective pre-reading

Prompt children to read with their pencil, meaning that their pencil moves across the page underneath each line as they read it. The benefit of training pupils to do this is that when it comes to underlining a key piece of information, their pencil is already in the correct location – it’s efficient.

2 | Underline key information

If you want pupils to underline key information as they read, they need to know what this means.

Consider the following categories:

- Names of people, places, companies, events, locations, etc

- Dates including days, months, years, times; statistics and numbers including percentages, fractions, amounts, figures, etc

- Words that pupils don’t understand (identifying them may still help pupils answer a question)

- Headings, sub-headings, images and punctuation

These areas can all help direct readers to the correct area of the text when answering a question.

3 | Spot key question words

Teach pupils to spot the key word or phrase in a question. This is a word or phrase that will signpost the pupil where to look in the text to find the answer.

In the following question, the key phrase is ‘Morse code’: ‘How did soldiers effectively use Morse code during the second world war?’.

If pupils have pre-read the text effectively, ‘Morse code’ should be underlined, or they may even remember where it is mentioned.

4 | Skim the text

Skimming a text is like looking at the chapters of a DVD and deciding which section or chapter of the film to start at. We won’t necessarily find the answer, but we hope to locate the correct area of the text and, ideally, the correct paragraph or section.

Ask pupils to first remember whether the information was at the beginning, middle or end. Is there an image or subheading that can signpost pupils to the correct area of the text?

5 | Scan for detail

Scanning is when pupils look at the specific section they’ve identified while skimming with a greater level of scrutiny, possibly looking for a key word or phrase.

Going back to the DVD analogy, this is like watching that specific section or chapter of the film to locate the information we require. Ideally this would be a specific sentence, phrase or word.

6 | Real-world examples

Introduce skimming and scanning by using images, timetables, TV schedules, poems, lists and visual instructions. Search online for ‘hidden word pictures’ and ask pupils to locate specific items, objects or information within them. Add a time limit to increase the fun factor.

7 | In, before and after

Once pupils have found a key word or phrase in a text, train them to read the sentence before, the one containing the key word and the sentence after. Doing this will give pupils a much greater chance of answering comprehension questions successfully.

8 | Simplify sequencing

Teach pupils to allocate a symbol (square, triangle, rectangle, star, cross, for example) to five different statements. Pupils should then find these statements in the text and draw on the corresponding symbol.

Once they’ve done this, it is extremely easy to look at the text and see which symbol comes first, second, third and so on. This is a very effective strategy to help pupils effectively sequence information.

Andrew Jennings is an assistant headteacher. He launched Vocabulary Ninja (@vocabularyninja) in 2017. Comprehension Ninja handbooks are available for Y1-6 (£24.99 each, Bloomsbury).