Autism Acceptance Month – Best 2025 ideas and teaching resources

Take part in Autism Acceptance Month at your school and raise money for a great cause…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Embark on a journey of inclusivity by celebrating Autism Acceptance Month in your school. Here we’ve rounded up a treasure trove of resources and invaluable advice to help you create an environment that celebrates neurodiversity in the classroom…

Jump to a section:

- Autism Acceptance Week teaching resources

- How to help autistic children manage stress

- Advice for working with autistic children

- AI tools for supporting autistic students

- Make PE lessons better for autistic pupils

- Why it’s OK for kids to ask about neurodivergence

What is Autism Acceptance Month?

Formerly known as Autism Awareness Week, Autism Acceptance Month aims to raise funds for the National Autistic Society. This money is used to support some of the 700,000 autistic people in the UK.

Money raised during Autism Acceptance Month goes to delivering plans to transform society into one that works for autistic people.

When is Autism Acceptance Month?

Autism Acceptance Month 2025 takes place during the month of April.

Autism Acceptance Month teaching resources

Great ways to help autistic pupils

This free eight-part series will give you practical advice for helping the autistic children in your class, not just during Autism Acceptance Month but all year long. There’s advice for helping autistic pupils to open up, how to make your school less threatening to autistic pupils and more.

Official resources and fundraising

If you plan to raise money for Autism Acceptance Month, join in with an official Spectrum Colour Walk or fundraise in your own way. Ideas for taking part include:

- hosting a colour quiz

- wearing a different colour each day

- having a rainbow-themed bake sale

- making meals featuring only one colour

- having a crazy hair day or fancy dress day

- hosting a colouring competition or art day

Download Autism Acceptance Month fundraising resources including posters, quizzes and more from the official website.

Elsewhere on the National Autistic Society website you’ll find lots of education resources, including Understanding autism online training. You can also sign up to an autism practice education newsletter.

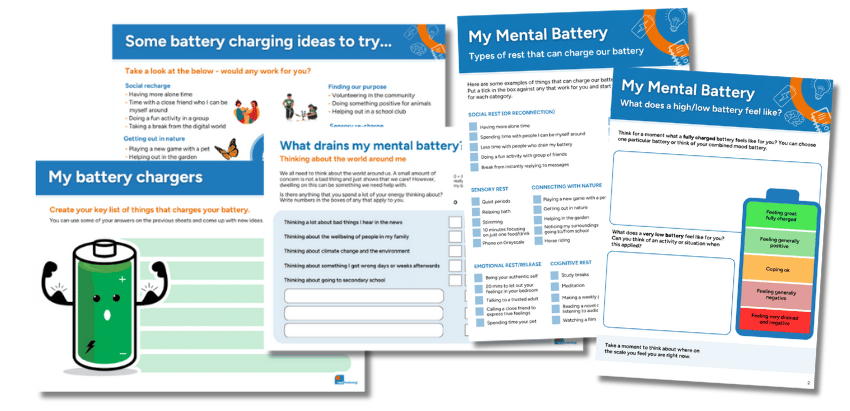

Recharging your mental battery

Psychologists Maja Toudal and Dr. Tony Attwood developed the concept of ‘energy accounting’ to help autistic people understand and manage their mental and emotional energy.

Building on this principle, these free mental health worksheets support autistic children and young people in recognising what drains and replenishes their energy.

With tailored versions for primary (Year 5+) and secondary (Year 8+), they encourage reflection on daily challenges and restorative activities, offering practical strategies to support emotional wellbeing.

Social skills lesson plan

Learn how to bring autistic children together in a structured, interesting task that will help them learn to get along together, celebrate their skills and help them learn new ones. Download the lesson plan for free and use it during Autism Acceptance Month.

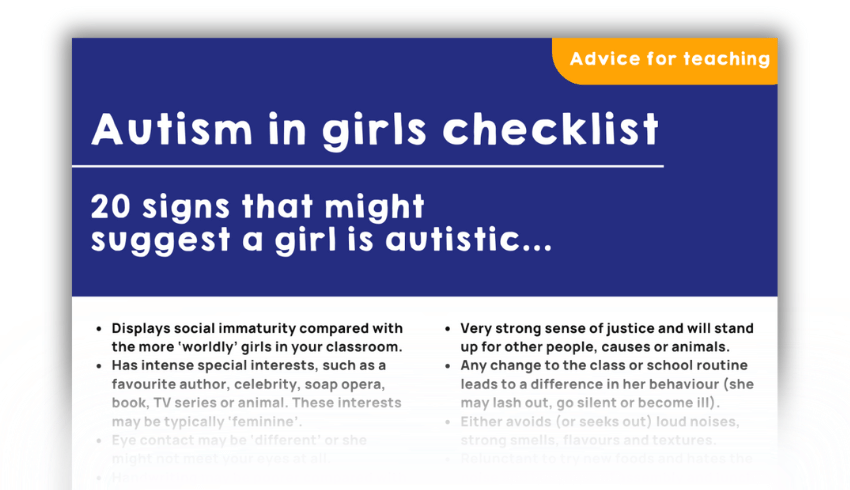

Autism in girls checklist

Signs of autism can often be masked by girls to fit in, feel safe and gain acceptance – but it can take a heavy toll for those on the spectrum. This autism in girls checklist resource for teachers lays out 20 signs that might suggest a girl in your class is autistic.

Blank faces templates

These free printable templates of faces are great for encouraging young children to understand and talk about emotions, develop social awareness and build relationships. Use them with children who might struggle with recognising or interpreting emotions.

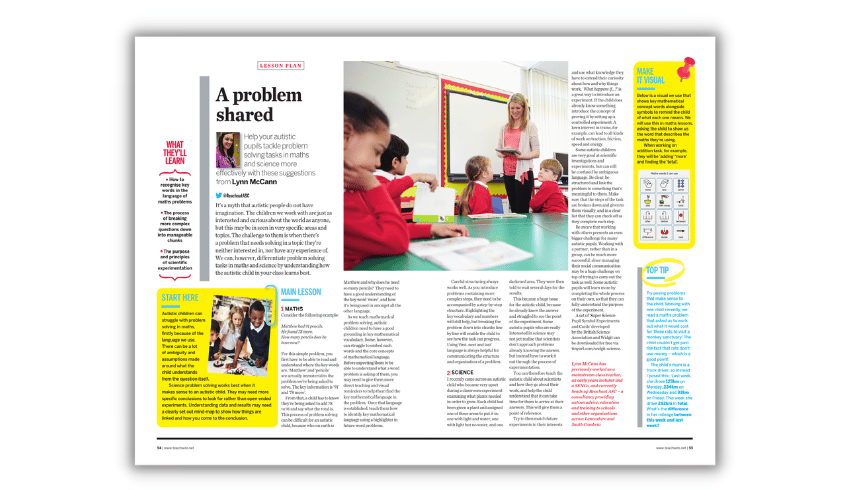

Problem-solving lesson plan

Help the autistic children in your classroom to tackle problem-solving tasks in maths and science with this free lesson plan for Autism Acceptance Month.

Autism Education Trust resources

The Autism Education Trust has a range of education resources on its website, including case studies about good autism practice in schools and advice for creating positive relationships between home and school.

Make storytime more engaging for autistic learners

This short video from Beyond Autism features seven simple ideas about how to help instil a love of reading and make story time engaging and fun.

How to help autistic children manage stress

Pete Wharmby explains why more steps must be taken to improve autistic students’ experience of secondary education…

It’s interesting to me that whenever autistic students are discussed by teachers, SENCOs and even parents, the issue of stress doesn’t come up much. If it does, it’s often in the context of the ‘stress’ these young people cause to ‘us adults’ in the situation.

Yet the reality of being autistic means that autistic students are likely to be extraordinarily stressed, all the time – perhaps in ways that even the most stressed teacher couldn’t comprehend.

I was diagnosed as autistic back in 2017, and have spent my time since then trying to communicate to the world what it’s like to be autistic, and how the world could perhaps meet us halfway and improve our lives.

Right now, the statistics aren’t good. Autistic people are four times more likely to develop depression, and autistic young people are 28 times more likely to think about, or attempt suicide. Part of that is the result of high levels of unsustainable stress taking its toll across the lifespan.

Unfortunately, this all starts at a young age, and the impact of the school environment can’t be overstated.

It’s so important that secondary schools do all they can to reduce the stress their autistic students experience every day. Luckily, this can be startlingly straightforward – so long as staff have a good understanding of what autism actually is, and are willing to make small changes to the way they run their classrooms.

An exhausting masquerade

Let’s start with where all that stress is coming from. The stress that autistic students typically feel will stem from a variety of sources, three of which we’ll examine here.

“It’s so important that secondary schools do all they can to reduce the stress their autistic students experience every day”

Firstly, autistic sensory sensitivity means that we’re constantly bombarded by unnecessary sensory information that fills our mental bandwidth.

The ticking of clocks, the smell of perfume, busy displays on walls – all contribute to our stress levels rocketing up. To get an insight into how this might feel, imagine trying to work diligently in a nightclub or a busy building site.

We’re also stressed by communication. The way we autistic people communicate is different to the non-autistic. We are direct, clear, unadorned speakers who avoid ambiguity and find eye contact difficult. We don’t tend to notice ‘unwritten rules’ or hierarchies.

Unfortunately, this natural style of ours is almost universally frowned upon by the non-autistic majority, so we learn early on that we must pretend and communicate in the ‘neurotypical’ way.

We call this process ‘masking’ – an intensely exhausting masquerade that we’re forced to endure. Since these communications aren’t natural to us, we struggle, get things wrong and are criticised. All the time.

Finally, we find it difficult to switch tasks in the ways you might be used to. It takes us longer and requires advance warning – rather like how a motorway will signpost junctions far ahead of time.

This is, in part, due to our monotropic brains. We’re great at establishing a deep focus and getting absorbed by tasks, but the payoff is that we need more time when switching to a new task. Something which is obviously very important within a school setting.

All of this, and so much more, can contribute to the extreme stress most autistic students feel. So what can be done?

Sensory audits

One of the first things any school should do for autistic students is what’s called a sensory audit, whereby an individual’s unique sensory profile can be established, since no two autistic people’s sensory experiences are the same.

I’m personally sensitive to sound and touch (including temperature), and have little sensitivity to taste. For other autistic people, these details will be very different.

Knowledge of what’s likely to cause distress is vital when adapting an environment; arranging a chat with the student, their family and friends can help you start to map out where their unique sensitivities lie.

The benefit of this is twofold. Firstly, it allows for reasonable adjustments to be made. Is the student better off sitting by a window with cool air and natural light? Do they struggle with the scratchy fabric of school shirts? Will teachers need to moderate their use of aftershave and room fragrances?

Rather than attempting to apply the same adjustments to every autistic student, make it individualised, and thus more efficient.

Secondly, it means that where adaptations can’t be made, you at least you know that their stress levels are likely to be higher around that sensory input. During a school trip’s coach journeys, for example, it’s near impossible to moderate sound levels.

Allowing a student to use ear defenders is great, but so is simply knowing that this student might be feeling a little fragile after the journey, and speaking with them on arrival to see if they need a quiet spot to sit down for a moment.

Simply knowing is one of the most powerful factors of change in all this. A compassionate, understanding word of support is valuable in and of itself.

Time and space

When it comes to communication, the best way to reduce stress is to streamline the whole process in an effort to avoid stressful overthinking. Communicate with autistic students in the clearest, least ambiguous way you can.

That means avoiding stock phrases, exaggerations and vagueness. Don’t say ‘Write as much as you can,’ as this will create anxiety (‘How much CAN I write?!’). Instead, say ‘Write 20 lines’ or specify a full page.

Don’t tell them off for misbehaving, but state clearly what it is they’ve done wrong and what the consequences will be (and be prepared to justify yourself, since many autistic people abhor injustice).

For older students, put things in writing via email as much as you can and don’t hint at things. State plainly what’s required and when it’s required by. If you actually mean ‘Get it to me tomorrow,’ then say so. Avoid qualifying that with ‘If you can, get it to me tomorrow’.

Finally, to avoid the stress of instant transitions between tasks, issue plenty of warnings, just like those recognisable to motorway users: ‘Your change of task is approaching in ten minutes, five minutes, 3…2…1…’ Allow the students time and space to switch tasks, or even let them carry on with whatever they’re absorbed in, if you can.

All this is only the beginning. There are a thousand more things I could recommend, but behind them all is the need to understand the autistic experience, and do whatever you can to reduce stress levels.

Just like every other human being on the planet, an autistic student can’t perform at their best when they’re stressed beyond their capacity. Schools are uniquely, if inadvertently designed to create stress for autistic people – so be a safe space in the maelstrom and promote autistic wellbeing.

General ideas for sensory adaptation

- Reduce the number of displays in classrooms

- Provide quiet spaces during break and lunchtimes

- Allow the use of ear defenders

- Allow the use of sunglasses indoors

- Let students write with paper ‘padding’ beneath their work if they feel they need it

- Don’t enforce eye contact – it’s extremely intense for most autistic people, and we hate it!

- Issue targeted advance warnings ahead of fire drills

- Be flexible with school uniform garments that may cause texture and/or temperature difficulties

- Remember that alexithymia can affect some autistic students, who may not be able to identify the source of their discomfort or the effect it is having on them.

- A big part of autistic masking is the perceived need to hide our own discomfort, knowing that no one else will take it seriously. Break that cycle!

Pete Wharmby is an author, speaker and tutor whose books Untypical (2023, HarperCollins) and What I Want to Talk About (2022, Jessica Kingsley Publishers) are available now; for more information, visit petewharmby.com.

Advice for working with autistic children

Lynn McCann from Reachout Autism Support Consultants explains how a tweak to your classroom or daily routine can bring huge learning benefits…

Autism is a lifelong condition and a different way of thinking. It affects boys and girls but often in different ways.

We can’t change an autistic child into one that thinks in a typical way. Instead, we need to understand how they think and build on that to help them learn.

Making your classroom environment simpler can have a calming effect on all children, but especially autistic pupils who are easily overloaded and distracted by the multitude of sensory messages.

They can find it difficult to know what to filter out, and those with hypersensitivities can find a ‘normal’ amount of noise, smell, touch or movement painful.

“Making your classroom environment simpler can have a calming effect on all children, but especially autistic pupils”

Others may need extra movement or other sensory input just to feel grounded in the space they are in. Here’s some ideas that may help:

- Leave clear spaces around whiteboards and between display boards. Try and keep displays simple.

- Make sure that the child’s desk is easily accessible so they don’t need to navigate obstacles or pass lots of other children closely to reach it.

- Check light levels, noise from other rooms and smells. Cut down on things hanging from the ceiling.

- Use table top vocabulary or maths reminders, rather than word or number walls, and only get them out as needed so they are not there all the time.

It’s always best to start with a minimum amount of sensory input and let the child tell you what they can cope with on top of that. As they settle in, involve the autistic child in discussion about what could go on the walls or on their tables.

Think about structure

Autistic children thrive on predictability. However, with preparation and support to understand how to manage the new situation, many autistic children can cope with new things.

It’s the unexpected that is likely to cause great distress for them. Try these ideas:

- Use a visual timetable and encourage the child to use it at every change of activity.

- Do what you say you will do, when you say you’ll do it, as much as possible. Don’t promise things you are unlikely to be able to do.

- Have the equipment the pupil might need easily available and well labelled. Start by putting maths or writing equipment in different coloured bags, for example.

- Use a visual schedule to help autistic pupils learn how to do things by themselves, such as getting ready for PE, packing their bag at the end of the day or tidying up.

- Try not to assume anything. If they are refusing to do something, do they know how to do it?

- Break down work tasks into manageable, clearly explained chunks. Fold a worksheet so only one part can be seen at a time or draw a coloured box around the part they need to do first.

- Use the words ‘first, then, last’ to help the child work through a task. Give them their own copy of a book.

- Pictures and written instructions are easier to refer to and remember than verbal instructions. Make them positive and encouraging.

- A workstation is a place to quietly get on with a set of tasks independently, without distractions. Some autistic pupils really benefit from having this space and structure to work with.

Boost inclusion

Social interaction is a two-way process. Working with your class to include and support an autistic child is important. Think about the following:

- Make plans to support your autistic pupil in interacting with his or her peers. This could be by setting up a games group, a buddy system for playtimes or by supporting partner work in class.

- Play and lunchtimes are unstructured times that can be a sensory nightmare. Allow autistic pupils to do things they like and help them find a calm space to refresh their batteries if that’s what they need.

Keep learning

Reading up about autism is helpful for teachers, but don’t assume the child in your class will be just like the ones you read about. My best advice is to get to know your pupil and their strengths, as well as their difficulties.

Don’t feel overwhelmed by what you might not know. Instead, ask for advice or help earlier, rather than later.

Here are some final ideas:

- Work as a team with your TA by planning together so that you both get to know the child well. Ideally you should be teaching the child yourself throughout the week.

- Getting to know the professional working with your autistic pupil and building an excellent relationship with them will bring huge benefits for all.

- Try and remain positive and calm. Behaviour is simply communication – try to ‘read’ what your pupil is trying to tell you.

- Build a good relationship with your pupil’s parents and accept advice and information from them. You’re in this together so find a structured way to communicate that suits you both.

Senior advisory teacher Victoria Honeybourne offers some tips for putting autistic pupils at ease when in school, but outside the classroom…

Pupils on the autism spectrum can find the mainstream classroom environment confusing and challenging, but what about the rest of the setting?

Schools aren’t usually designed for autistic pupils, and shared spaces can be just as difficult to navigate as the classroom itself.

It may not be possible to redesign your entire school, but some simple adjustments can make a big difference.

Differences in perception

Pupils on the autism spectrum can often experience sensitivity to sensory stimuli. They may be over- or under-sensitive to any of the senses – touch, smell, taste, sight or sound.

Complex patterns and colours may appear overwhelming and disorientating, or background noise can appear amplified, making it difficult to concentrate.

In addition, some pupils experience difficulties with proprioception – awareness of where their body is in space. Some may appear clumsy, stand too close or too far away from others, or may ‘hold on’ to walls and furniture to help them move around a room.

All of these differences can increase anxiety and frustration, making it difficult to focus, interact and cope. For many pupils sensory overload is not only uncomfortable but actually painful, and some pupils may go into ‘shutdown’ or ‘meltdown’ as a result.

So how can we make shared spaces more autism-friendly?

Navigating the school

Corridors and open shared spaces can present specific difficulties. With space at a premium in many schools, it can be easy for these areas to become cluttered, crowded and used for multiple purposes.

Define the use of each space. Create different ‘zones’ through colour-coding, clear signs and helpful visuals. Furniture or display boards can also be positioned to create specific areas, such as a cloakroom or silent reading area.

Use natural lighting where possible. It can become a habit to turn lights on when they’re not needed – some autistic pupils can be particularly distressed by fluorescent lighting.

“Create different ‘zones’ through colour-coding, clear signs and helpful visuals”

Low tables and storage boxes can be difficult for children with poor spatial awareness, so keep furniture against the wall to prevent trips and bumps.

Brightly coloured walls brimming with work and posters are a feature of many schools, but can be overwhelming to some autistic pupils. Keep displays tidy, relevant and use neutral background colours.

Narrow corridors can induce anxiety in pupils who are uncomfortable in groups of people. Dismiss one group of pupils at a time, or else introduce a one-way system.

Assemblies and larger gatherings

Larger gatherings can also create anxiety for some pupils. Some children may feel more comfortable at the end of a row or near the back rather than at the centre of a crowd of people. Others may find it difficult to know how close or far away to sit from other pupils.

You could try using masking tape to indicate the distance needed between one row of pupils and another, or have a clear rule (one pupil per carpet tile, for example).

“Larger gatherings can also create anxiety for some pupils”

Visuals can also be helpful to give all pupils some clear guidelines (eg ‘When queueing, the person in front should be an arm’s length away’). Space out rows of chairs so that pupils do not feel squashed.

Remember too that some pupils on the autism spectrum may be particularly sensitive to noise. If a video or music is playing, they might be more comfortable sitting further from the stage or away from speakers.

Trending

Social times

Morning breaks and lunch hours are often cited as times of difficulty for autistic pupils, typically due to the lack of structure and emphasis on socialising.

Structured activities and games led by an adult may help some pupils understand how to participate.

Create a space (indoors or on the playground) for arts, crafts and toys. This will allow autistic pupils to engage in an individual activity while still being in the company of others, reducing their feelings of isolation and loneliness while removing the anxiety of having to interact.

Buddy benches may also be beneficial. Provide a bench where any child can sit when they would like to join in with others or are feeling lonely.

“Structured activities and games led by an adult may help some pupils understand how to participate”

Other pupils can be encouraged to keep an eye out and help those sitting on the bench to take part in whatever they’re doing.

Clear zones can be helpful on the playground. Signpost which areas are for running, which are for ball games, where toys can be played with and other similarly zoned activities.

Some autistic pupils will need to spend social times alone; the interactions of lessons can be enough for them, and they’ll require ‘alone time’ in order to recover.

Provide quiet spaces which are kept quiet and peaceful. Allowing any pupil to make use of these whenever they need to will reduce any stigma that might become attached to them.

Mealtimes

Dining halls can be especially difficult due to the mass of smells, people, noises, tastes, textures and movement that children will encounter in them. A child with heightened senses might be able to hear every crunch and every rustle of a crisp packet as loudly as their own!

Devising clear dining hall routines for lining up and eating can be helpful, as can providing quieter areas.

Adjustments of this type to the wider school environment will typically help many pupils, not just those on the autism spectrum. As pupils become older, encourage them to take more responsibility for developing their own individual coping strategies for their personal needs.

This will empower them to be able to cope independently with secondary school and subsequently everyday life.

Victoria Honeybourne is a senior advisory teacher, writer and trainer, and has a diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome. She is the author of Educating and Supporting Girls with Asperger’s and Autism.

AI tools for supporting autistic students

Sarah Haythornthwaite, go-to-market director at RM Technology recommends some AI tools to help support your autistic students…

Opening up opportunities for students with autism requires the development of a supportive learning environment that can adapt to their needs.

You may have previously lacked the technological resources to build this environment, but the emergence of accessible AI tools is changing this.

From data-driven analysis to personalised instruction and support, AI is quickly becoming the most effective tool in a teacher’s arsenal to help autistic students.

Understanding how to deploy these tools productively in the classroom can give students the support they need to realise their full potential.

Giving students the right tools

AI education tools, such as CognitiveBotics, offer AI-powered assistive technology to create and run lesson plans tailored to individual children’s needs. This ensures targeted skill development that you can then supplement.

Other tools, such as Facesay, support autistic students with emotional learning. This software uses interactive games to help those who struggle with recognising different emotions.

Microsoft Reflect, which is a free tool for Microsoft users, allows you to easily set up regular check-ins for students. The Feelings Monster, which lives within the Microsoft educational app, can assist you in understanding what students are feeling in your classroom. It helps students with autism build their emotional intelligence.

For schools which use Google for Education, there is a wide range of materials available online which can help you understand how to customise learning tools to create an inclusive learning environment.

Helping autistic students find their voice

Whether an autistic student is verbal, nonverbal, or somewhere in between, they may need your help and encouragement to find their voice.

AI tools, such as ChatGPT and Gemini, can give students a way to find the right words to express their, thoughts, emotions, and needs without judgment or pressure.

The user-friendly nature of these popular platforms makes them accessible to most people, including those with nonverbal autism. They can leverage the chat service to perform a variety of tasks and act as a communication partner in the classroom.

Sarah Haythornthwaite is go-to-market director at RM Technology, which creates innovative technology solutions for all students, including those with SEN. Sarah is also a trustee of the Autism Education Trust and a fundraiser for her local inclusive football team.

Make PE lessons better for autistic pupils

Special needs teacher and author Adele Devine shares some advice for opening up gym classes and team games to students on the autism spectrum…

You arrive at work and are handed a dirty, smelly PE kit. “Get dressed and be on the field in five minutes!” You try to protest, but get shouted at. Maybe it’s rugby, rounders or hockey? It’s raining and your head’s starting to ache. You weren’t expecting this.

How would you feel? The school day can be a social minefield for a student on the autism spectrum. Anxieties from noises, unexpected changes, smells and social pressures can all cause genuine pain, and adding a PE lesson may feel like we’re rubbing salt in the wound.

Just think of the obstacles that autistic learners can expect to face in PE. In addition to overwhelming anxiety, there will be the need to put on different clothes in the environment of a changing room, which can present issues with regards to their personal space and body confidence.

Throughout the lesson, they may feel a near constant uncertainty over where to stand, what to do and what’s happening next.

Then, after all that, come the PE activities themselves and all that they entail – choosing teams, the way team games can highlight a child’s lack of coordination (which will be made even worse if the child has a tendency to perfectionism) and the general lack of order.

With that in mind, here are 10 supports that can go a long way towards making PE lessons more inclusive for students with autism.

First impressions

Set aside specific areas for warm-up activities. Seeing a big ball to bounce on, equipment for practising balance skills or a goal for shooting baskets will mean the student can immediately see there’s something they can go and do.

Create an atmosphere where there’s clear order, and establish rules so that students know when it’s time to stop and listen. Rules and order make things feel safe.

Changing rooms

Changing for PE may trigger anxieties. Providing a set space so that personal belongings can be kept in order can make a massive difference.

Could changing be staggered to avoid the rush? A visual schedule may help prompt students on what to do next. Do they know why it’s important to change for PE?

A Social Story (see carolgraysocialstories.com) may help explain this in a non-threatening, factual way.

Time

Sometimes all the autistic student needs is time to process and adjust to the environment. Allow some time at the start of the session before any demands are placed.

Be aware that they may take a little longer to process when you speak to them. Use their name to gain their attention and keep language quite simple. A visual sand timer or clock display may help those who find PE activities difficult to endure.

Routine

The unexpected can trigger anxiety. A set routine will allow the student to know that there’s predictability and order to your session.

Start with setting out fun things to explore, then have the same warm-up, followed by an activity and a similar cool-down at the end. The more the student with autism gets to know a pattern, the safer and happier they’ll feel.

Schedules

Providing a visual schedule to break down the stages of the session can make a huge difference. You don’t need to go cutting out pictures and laminating – try using large flipcharts or dry wipe boards and breaking the lesson down into three or four sections, with stick figures showing what students will do.

Cross things out as you go. Think how we count down the stops on the train. Knowing helps…

Visuals

A visual can let the students to see exactly what you’re trying to explain. It’s a point of reference they can refer back to if they don’t process as quickly.

Visuals reduce the need for lots of verbal instructions; it can be easier to tolerate instruction from a visual than from a teacher.

Space

When discussing this article with our PE specialist Amy Harwood, the first of her many useful suggestions was “Floor spots”.

She always carries multi-coloured rubber floor marking spots, since they help to show students exactly where they need to be, providing an instant visual for many different types of activity.

Support

Find out about the individual student. What are their motivators? What will they find challenging? Observe and set them up to succeed.

Don’t allow the choosing of teams – this is a cruel tradition which can only cause social discomfort. Why not select teams in different ways? Maybe one week do it by the benches the students have sat on; another week, number them ‘1, 2, 3, 4’ or hand out differently coloured bibs.

Breaking things down

Providing a visual breakdown can make things less overwhelming. Skills develop in stages, so before playing tennis they must first learn to throw and catch, handle the racket and hit balls served to them.

Set things up so that there are opportunities for students to practice discreet skills. Without a visual breakdown the student may feel frustrated that they’re not instantly perfect and give up.

Praise

All students respond to praise. It’s an essential and easy way of providing positive feedback, showing that the student is on track and building their self-esteem.

Look at what they’re achieving and show them that you appreciate their efforts and that they’re getting better all the time.

Reward charts may help some students, but not all. Keep smiling, be overly patient and be predictable. Never, ever shout!

Final thoughts

As the retired pro basketball player Michael Jordan once pointed out, “Obstacles don’t have to stop you. If you run into a wall, don’t turn around and give up. Figure out how to climb it, go through it, or work around it.”

We must set our learners with autism up to succeed by pre-empting and providing the supports they may require.

Most importantly, we must build their self esteem and confidence so that they believe in themselves. Reveal their potential and praise them for having a go!

Why it’s OK for kids to ask about neurodivergence

With a little under three years between my boys, the school nursery run with the younger inevitably meant catching sight of the elder in the playground at lunchtime. Always alongside him was his additional support needs worker, who is still such a huge part of our lives today.

But, as we queued for pre-school, we would pull in quite a crowd at the fence. Classmates of my elder son (then six) physically lined up to ask us questions about big brother: Why did he do that thing? Make that noise? Jump that much? Say that phrase? Feel that way?

Far from being annoyed by the many enquiries, I embraced them. Regardless of a particular question and how many times it had been asked by various kids over many, many months, we answered it in the fullest way we could. Every time.

“Far from being annoyed by the many enquiries, I embraced them”

True inclusion

You see, those questions – those answers – are essential if true inclusion is ever to work. In every other sphere of life, we encourage enquiring minds and propagate inquisitiveness and persistence. Yet when it comes to something as vital as teaching kids about their neurodivergent classmates, we all too often get bashful.

If knowledge is power then knowledge denied is surely, what, fear? Perhaps that’s too strong a word. But it’s a sense of incompetence and inadequacy at the very least.

Children, like so many adults, can feel inadequate around their neurodivergent peers. Those like my son, who need something different from those around him if he is to stay regulated, feel safe and be able adequately to function – let alone be his full, vibrant self.

There is, in the education system in the UK, a presumption of mainstream for children with additional needs, even when those needs are pervasive and complex.

Not all the same

Of course, there is a sad history of autistic people being locked up, hidden from society and isolated: how truly unthinkable. But additional needs support is not about binaries, and the way to address the truly horrific way in which autistic people were treated in the past is not simply to assume sameness and throw everybody together to prove we are all equal.

The fact is, we’re not all the same; and so many times, we hear of schools failing neurodivergent children precisely because individual needs are being ignored in the name of misguided ‘inclusion’.

Inclusion is explicitly not about being the same: it’s about recognising individual needs and making all necessary accommodations to allow that person to feel safe, secure and understood.

“Individual needs are being ignored in the name of misguided ‘inclusion’”

A huge part of that involves teaching our neurotypical young people more about their neurodivergent peers and how they can help them.

Let’s not get hung up on the semantics of whether somebody ‘is autistic’ or ‘has autism’, or on the ever-changing terminology that baffles and intimidates the most empathetic, kind people into silence.

OK to ask

The six-year-olds hanging over the school fence, chomping crisps and wiping noses, asked some of the most pertinent questions ever posed to me about my son. They had the right idea: it’s okay just to ask.

Even my younger boy, who has never known anything other than his autistic big brother, still has occasional questions. Yes, even amid his vast, absorbed bank of lived knowledge and overflowing kindness. And it wouldn’t occur to him not to ask.

My elder son has attended a specialist school for the last two years. He needs the extra help and attention, expertise and tailored experience that a special provision offers.

He’ll attend a specialist secondary school and will, most likely, never be in a mainstream classroom again.

But he is understood so much more by the myriad of other children and adults around him in everyday life because of those snatched conversations with kids hanging over the fence.

If true inclusion is the aim, as it should always be, then we have a duty to show children, time and time again, that it’s okay to ask.

Answer their questions: whenever they come, however they come. Child by child, class by class, school by school, lives can be changed forever.

Fiona Carswell is the author of The Boy Who Loves to Lick the Wind, which is out now in hardback (£12.99, Otter-Barry Books).