Working memory – Why schools should pay attention to it

Working memory plays a crucial role in learning. Here’s how to identify and support children with working memory challenges…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

A child who has working memory issues may do less well in things like reading, writing, and maths. The good news is that there is a lot that we can do, once we know what signs to look for…

What is working memory?

The most important ability children develop for learning is their ‘working memory’. If you’re not already familiar with the term, it describes when we hold onto / store information in our head for a short period of time (i.e. seconds) and use or process this information in some way.

How common are working memory issues?

A government-funded study of over 3,000 students found that 10% of students have working memory problems that lead to learning difficulties in the classroom. That’s around three children in a class of 30.

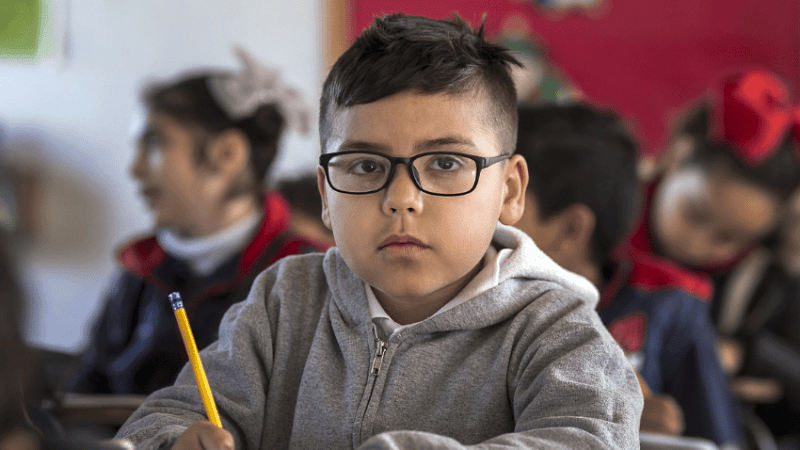

Common working memory problems that children show in the classroom include:

- forgetting instructions

- losing their place in an activity

- raising their hand but forgetting what they want to say

- struggling to cope with tasks involving simultaneous processing and storage

- abandoning activities without completing them

Students considered by their teachers to have problematic behaviours are more likely to have low working memory scores and hence achieve low grades.

Students who display problematic behaviour associated with working memory issues will not necessarily have low IQ scores. Indeed, many can have average IQ scores.

It’s working memory overload that leads to the behaviours. Their loss of focus in tasks can make them appear inattentive and distracted to others.

Why does working memory matter?

Working memory is important for a variety of activities at school. This includes complex subjects such as reading comprehension, mental arithmetic and word problems, to simple tasks like copying from the board and navigating around school.

Without support, a student with working memory issues will struggle to catch up with their peers. A study with high schoolers found that teenagers diagnosed with working memory problems were still performing very poorly in school compared to their peers two years later.

Is working memory the same as IQ?

Working memory is not the same as IQ. A child can have working memory issues and a very high IQ, or the other way round.

Working memory is an accurate predictor of learning from kindergarten to college because it measures potential to learn. This is opposed to what a pupil has already learned.

In contrast, other measurements like school tests and IQ tests measure knowledge that children have already learned.

If students do well in one of these tests, it’s because they know the information we’re testing them on. Likewise, many aspects of IQ tests also measure knowledge that we have built up.

A commonly used measure of IQ is a vocabulary test. If they know the definition of a word like ‘bicycle’ or ‘police,’ then they will likely get a higher IQ score.

If they don’t know the definitions of these words, or perhaps don’t articulate them well, this will be reflected in a lower score.

In this way, IQ tests essentially measure how much students know, and how well they can articulate this knowledge.

How are dyslexia and working memory linked?

Pupils on the dyslexia spectrum are easy to spot. They tend to think faster than they can read, write, spell and get their ideas down on paper.

Another common marked difference in competency involves a a pupil’s age/ability-appropriate verbal or perceptual reasoning coming up against unexpected issues relating to their working memory and processing speed. Brock and Fernette Eide highlight this in their 2011 book The Dyslexic Advantage.

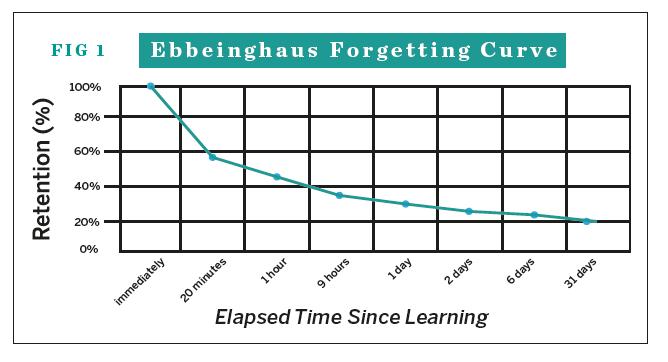

Dyslexic pupils can present as not understanding, when in actual fact they have often forgotten what to do next. In effect, they are ‘quick forgetters’. The challenge is to overcome the ‘forgetting curve’.

The forgetting curve shows how pupils forget 20% of a lesson upon leaving the room and a further 20% during a 20-minute playtime. They can only recall around 33% of the lesson the next day.

That’s one reason why our content-heavy national curriculum is so difficult to cover without applying some research-validated principles to our teaching. It also explains why pupils on the dyslexia spectrum can struggle to show their true ability.

How can you spot working memory issues in children?

The Working Memory Rating Scale (WMRS) is a behavioural rating scale. It helps educators easily identify students with working memory deficits.

It consists of 20 descriptions of behaviours characteristic of children with working memory deficits. Teachers rate how typical each behaviour is of a particular child using a four-point scale:

- 0 (not typical at all)

- 1 (occasionally)

- 2 (fairly typical)

- 3 (very typical)

Since the WMRS focuses solely on working memory-related problems in a single scale, it doesn’t require any training in psychometric assessment prior to use.

It’s valuable not only as a diagnostic screening tool for identifying children at risk of working memory deficits, but also in illustrating both the classroom situations in which working memory failures frequently arise, and the profile of difficulties typically faced by students with working memory issues.

Taking age into account

The scores are normed for each age group, meaning they are representative of typical classroom behaviour for each age group.

For instance, one of the 20 WMRS descriptions is ‘Needs regular reminders of each step in the written task.’ The classroom teacher has to rate how typical this behaviour is of the student. They then compare their score to the manual.

A five-year-old needs more reminders than a ten-year-old. This is reflected in the scoring of the WMRS; the scoring is colour-coded to make it easy to interpret.

A score in the green range, for example, will indicate that it’s unlikely the student has a working memory impairment.

If a student’s score falls in the yellow range, it’s possible that they have a working memory impairment. The recommendation will be that you need to do further assessment.

Scores in the red range indicate the presence of a working memory deficit. In this case, targeted support is recommended.

The WMRS enables teachers to use their knowledge of their students to produce an indicator of how likely it is that a child has a working memory problem. Thus, it provides a valuable first step in detecting possible working memory failures.

How to improve working memory

Brain training

We can train working memory. Brain training is a growing and exciting new area – there’s much evidence of the brain’s plasticity, that it can actually change depending on what we do.

Clinical trials with a working memory training program called Jungle Memory demonstrated improvements in working memory, IQ and learning outcomes.

Mastery learning

Mastery learning is based on the premise that most pupils can learn most things, given enough time and appropriate teaching.

Trending

To that end, learning becomes the constant and time the variable, especially when grooving in key skills, but there’s an opportunity cost involved.

In this case, the ‘cost’ is teaching less content in the early stages. We balance this against the opportunity to teach a little less a little more effectively, safe in the knowledge that we can pick up the pace once children have embedded core skills.

Mastery learning for quick forgetters therefore involves the following principles:

Demonstration of mastery

Each lesson begins with a quick demonstration of mastery. Working with a partner to jot down three important points from the previous lesson, without needing to be told, is a quick demonstration of mastery. This helps bring quick forgetters up to speed.

Each lesson also ends with a demonstration of mastery. This enables teachers to assess the impact of their teaching and sets imperatives for subsequent differentiation and personalisation.

Research has shown that ‘low stakes/no stakes’ quizzes at the end of lessons can double the rate of retention.

Getting pupils to create the questions themselves further increases this impact by harnessing the power of peer tutoring.

Revisiting content

Ideally, only 15% of a lesson should be new; lessons should re-visit up to 85% of the content, knowledge, skills and concepts from the preceding lesson and continue in that vein.

By teaching less content early on in a Key Stage, schools can ensure that core skills are properly taught, firmly embedded and ready for development later in the syllabus.

From the perspective of quick forgetters, this memory-light approach provides frequent opportunities for re-visiting. ‘Overlearning’ in this way also creates episodic memories based on what’s gone before.

I say, we say, you say

The final principle is to adopt the ‘I say, we say, you say’/‘I do, we do, you do’ mantra, rather than ask “Who can tell me?”.

The former ensures that pupils start with a correct model and get it right first time. Quick forgetters are liable to remember things that they’ve learnt incorrectly and have to be subsequently corrected, such as their spelling of ‘eny’ (any) and ‘thay’ (they).

Rather than attempting to change the habits of a lifetime, it’s better to get everything right first time.

Spaced review

The next step towards empowering quick forgetters is to ensure their learning is checked regularly throughout the lesson.

Spaced review consolidates learning and highlights any problems and misconceptions, giving teachers regular feedback on the impact their teaching is having.

The ideal ‘space’ between each review depends on the attention span of the class and/or individual. There’s a simple formula you can use for this:

Attention span (in minutes) = chronological age + 2

The typical attention span of an eight-year-old will therefore be ten minutes, and so on. Although pupils will appear to concentrate beyond this notional figure, each minute thereafter becomes subject to the law of diminishing returns.

Having begun with a demonstration of mastery from the previous lesson, after every ten minutes or so we will therefore need to inject quick ‘assessment for learning’ activities to check our impact so far.

The feedback from these activities will then determine the direction of the lesson for the class and/or individuals, as it becomes clear that some are ready to move on while others need more time.

Assessment for learning

Dylan Wiliam suggests that formative assessment can double the speed of learning, because it builds on all the principles outlined above.

Using a range of formative strategies helps to gauge the impact of teaching and ensures that we teach the pupils, rather than the lesson.

Example lesson

A 60-minute memory-lite lesson for 13-year old-quick forgetters (with a notional attention span of 15 minutes) might therefore look like this:

Minute 1: Quick demonstration of mastery – three key points from last lesson.

Minute 16: “Tell your neighbour the most important point so far – then share with the table.” Warn some quick forgetters that they’ll be asked to share with the class, but check discreetly that they’ve got a good answer before going public.

Minute 31: ‘Muddiest point’ – pupils work with a partner or their table to identify one thing that isn’t clear. This harnesses the power of peer tutoring; anything which can’t be resolved this way obviously needs re-teaching, so it’s a win-win.

Minute 46: Prepare a quiz question that a teacher might ask.

Minute 59: Quick demonstration of mastery using pupil-generated quiz questions

To reiterate, there’s a cost to working in this way, in that less subject content can be covered during the early months of the year.

However, there’s also an opportunity – what you teach will be remembered much more effectively. The teaching and learning can then accelerate as the year unfolds.

- Check mastery at the beginning and end of lessons.

- Use the ‘attention span rubric’ to chunk more – aim to teach a bit less, a bit more effectively.

- Use a range of ‘assessment for learning’ activities to monitor the impact of your teaching.

- Plan accommodations around ‘dyslexia time’, working on the basis that it will take twice as long to produce half as much.

- Use a ‘hands down’ approach to class questions – allow pupils time to process, take up and think, before telling their partner and then the rest of their table.

- Focus on your quick forgetters by telling them ‘The next question is yours’ – but only ask it after allowing them take up and discussion time, and discreetly checking that the answer will be correct. There should be no putting pupils on the spot for quickfire answers unless the individuals are sufficiently confident.

Thanks to Dr Tracy Packiam Alloway and Neil MacKay for their help with this article.

Dr Tracy Packiam Alloway is a psychologist and author specialising in the research of working memory in the context of ADHD, dyslexia, autism, anxiety, and other difficulties affecting children’s learning. She is the author of How Can I Remember All That? (Jessica Kingsley Publishers).

Neil MacKay is an experienced teacher and freelance consultant and trainer. For more information visit actiondyslexia.co.uk or follow @ActionDyslexia.