Retrieval practice in the classroom – Boost long-term knowledge retention with this powerful learning strategy

Use these retrieval practice examples, activities, templates and ideas to help students recall previously taught information…

- by Teachwire

What is retrieval practice?

Retrieval practice is a “simple research-based teaching strategy” that involves students retrieving and bringing information to mind. The challenge of remembering this information produces durable long-term learning.

In this episode of The Cult of Pedagogy podcast, Jennifer Gonzalez speaks to Pooja Agarwal about what retrieval practice is and how you can start incorporating it into your classroom right away.

JUMP TO A SECTION

- How to boost information recall in the classroom

- Retrieval practice examples

- Retrieval practice activities

- Kate Jones retrieval practice templates

- More retrieval practice teaching methods

- Using retrieval practice as a revision tool

How to boost information recall in the classroom

If your pupils struggle to recall yesterday’s lesson, prompt them to retrieve information from memory by embedding regular quizzes into your curriculum design, with these ideas from Jon Hutchinson, director of training and development at the Reach Foundation…

Back in the 1880s, when Hermann Ebbinghaus measured the rate that which information is lost after initially learning it, the conclusions were clear: everybody forgets things unless they revisit that information regularly.

“Everybody forgets things unless they revisit that information regularly”

These results have since been repeated in multiple contexts and under a huge variety of conditions.

In the classroom, this means that we shouldn’t be entirely surprised (or cross) by our pupils struggling to recall their initial learning from yesterday’s lesson. Indeed, it is an inevitable and perfectly natural part of the learning process.

Our job is to interrupt this forgetting, by using effective strategies to prompt children to retrieve information from memory.

Embed multiple-choice quizzes into your classroom practice

It is for this reason that, as part of our curriculum design at Reach Academy Feltham, we have embedded regular multiple-choice tests and quizzes into our curriculum design to help us reap the benefits of retrieval practice.

Aside from Ebbinghaus, our decisions have been influenced by more recent research into retrieval practice, spearheaded by professorial power couple Robert and Elizabeth Bjork (very much the Beyoncé and Jay-Z of the cognitive science world).

Retrieval strength and storage strength

They suggest that any information tucked away in our memory can be measured in two ways.

First, there is the speed at which you can recall some fact or skill: the ‘retrieval strength’.

Second, we can consider how well connected and robust the knowledge is – known as ‘storage strength’.

New information which is not linked to anything else stored in your long-term memory will have a low retrieval strength, as well as a low storage strength.

This is the reason that they write the hotel room number on your card when checking in: you will probably forget it.

By the end of the week, the retrieval strength of your hotel room number will have increased, by regularly having to recall it. However, the storage strength is likely to remain low; you probably won’t be able to recall it in a year or two.

Other information – perhaps the name of a child in your class back at primary school – could have a high storage strength (they are connected to tonnes of other memories) but a low retrieval strength (what was their name again? Patrick? Peter?).

Finally, information can have both high retrieval and high storage strength. An example might be the name of your current best friend.

This, of course, is what we are aiming for in what we teach. And based on what we know about how memory works, we think that the testing effect is an indispensable tool to achieve it.

Retrieval practice examples

We can capitalise on this in lessons in a few different ways. First, always begin a lesson with retrieval practice – a short quiz, including five, multiple-choice questions of previously learnt material.

Beginning with a retrieval practice technique ensures a calm, focused and motivational start to the lesson.

Let’s take an example. In the first lesson of our unit on Roman Britain, the class learn about how Romulus killed his brother to found the city.

Within that lesson, there will be some key facts that we don’t want the children to forget. So the very first thing that we do at the start of the next lesson is ask all children to answer the question, “According to myth, who founded Rome?”

These quizzes have no stakes. That is to say, we don’t collect any scores, and we don’t tell children off or express disappointment if they get a question wrong. That is not the purpose.

Instead, what we are trying to do is deliberately interrupt the forgetting curve. It is better to think of this regular quizzing as a student learning event in itself, as opposed to an assessment.

“What we are trying to do is deliberately interrupt the forgetting curve”

It doesn’t really matter whether the children get the question right or wrong; they benefit either way from this effective learning technique.

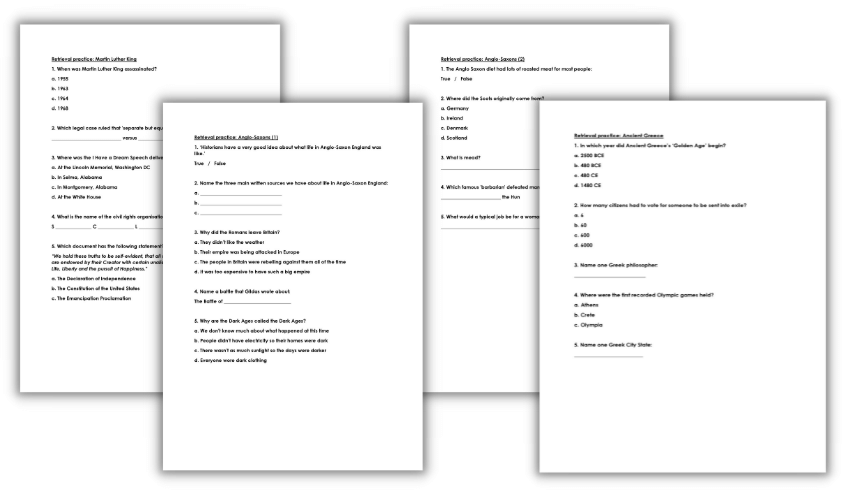

Ancient Greece retrieval practice quiz example

- In what year did Ancient Greece’s ‘Golden Age’ begin?

- 2500 BCE

- 480 BCE

- 480 CE

- 1480 CE

2. How many citizens had to vote for someone to be sent into exile?

- 6

- 60

- 600

- 6000

3. Name one Greek philosopher

4. Where were the first recorded Olympic games held?

- Athens

- Crete

- Olympia

5. Name one Greek City State

Retrieval practice activities

Writing good multiple-choice questions is devilishly difficult. Ours focus on the most important things we want children to remember from previous lessons.

A knowledge organiser is a good learning tool to start from here, as it should include the core information.

I often begin planning a lesson by asking myself, “What are the five things that I want all children to remember by the end of this lesson?” These then become the targets for quiz questions in the following lesson.

“What are the five things that I want all children to remember by the end of this lesson?”

In the example about Roman Britain above, we would include the correct answer (Romulus), but then also add in plausible distractors. These would include Remus, Julius Caesar and Tiberinus (the god who saved Romulus and Remus from the river).

Children rack their brains, circle what they think is the correct answer, then move on to the next question.

A few minutes later, I’ll switch to the next slide which has all of the correct answers on, and pupils can self-mark, correcting anything they got wrong.

While this takes place, I’ll whizz around the classroom and make a note of any common misconceptions. The whole episode takes around five minutes.

So, while quizzing may not be the flashiest or most fashionable classroom activity, there is an abundance of science outlining the learning rewards.

Mistakes to avoid

When I first began using test-enhanced learning I made a few mistakes that reduced the effectiveness of retrieval practice. The first was using funny or wacky answers within the distractors.

Since I very much consider myself to be an as-yet-undiscovered comedian of world-class talent (who is, frankly, wasted on primary school children), I can’t resist popping in a humorous answer to elicit a giggle.

When asking the pupils “Why did Alexander the Great weep?” I’ll want to include an option like, “because the Nando’s in Persia had run out of chicken” (wasted, I tell you).

The problem with adding in these silly options is that they distract children from what you actually want them to remember (that “there were no more worlds to conquer”).

They’ll tell you about how funny it was to think about Alexander having a Nando’s. Some children may not get the joke and actually think Alexander the Great did eat Nando’s.

The correct answer, a wonderful piece of cultural knowledge and a useful window into the success and ambition of the Macedonian King, gets lost somewhere in laughter. The kids just remember Alexander eating a Nando’s.

“Some children may not get the joke and actually think Alexander the Great did eat Nando’s”

The second mistake is to let children look back at their notes. In doing so, we kill the benefits of the testing effect, because children do not have to try and recall from memory; they are just rereading and copying down the answer.

It may seem counterintuitive, but that effortful struggle is exactly what produces the strengthened retrieval in future.

Kate Jones retrieval practice templates

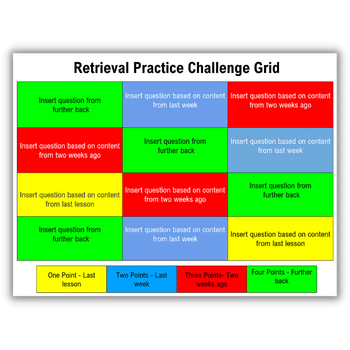

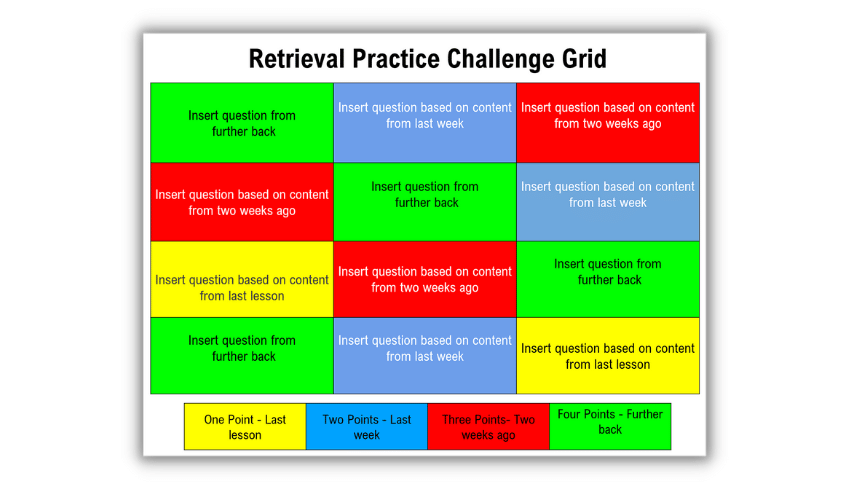

Teacher and author Kate Jones explains how to use her retrieval practice challenge grid at the start of your lesson...

I designed the retrieval practice challenge grid to help you purposefully revisit subject knowledge and content previously studied.

The questions differ based upon when the subject content was taught. The further back this was, the higher the number of points on offer.

I use this approach at the start of a lesson as it includes a wide range of questions that require students to recall information from last lesson, last week and even further back – it’s a simple and efficient way to begin.

Five a day method

We are all familiar with the ‘five a day’ message as it applies to including portions of fruit and/or vegetables as part of our daily routine to stay healthy.

This concept can be applied to the classroom with a twist, focusing on a daily review of five a day to promote healthy retrieval. It could simply be five quiz questions to start the lesson.

Another idea is to have five keywords on the board. Students must define each one or write a paragraph summarising previous learning including all five words. Alternatively, they can create five questions where each keyword is the answer.

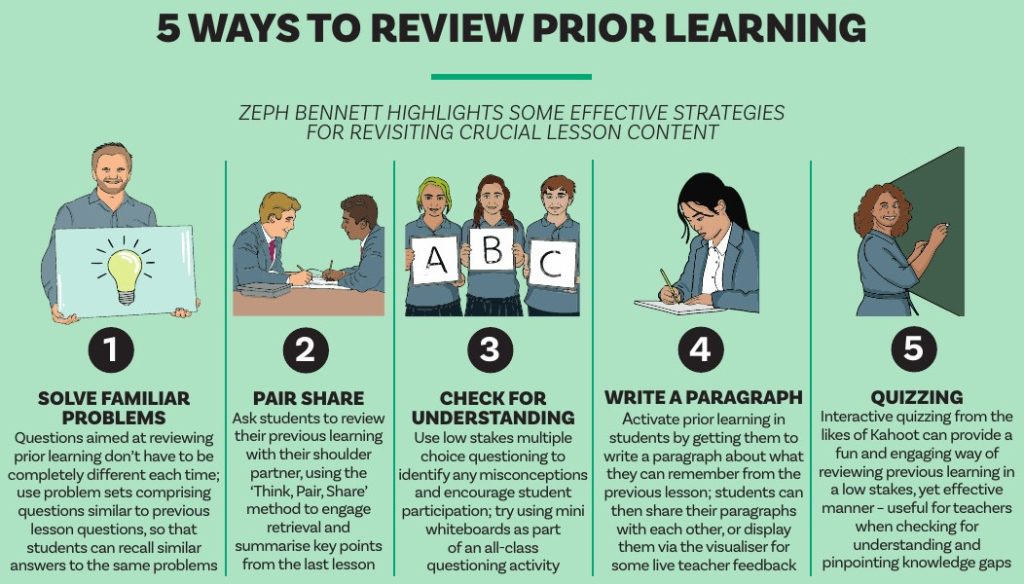

Below you can see examples of teachers using retrieval practice tests in several different ways to encourage effective retrieval practice.

More retrieval practice teaching methods

Make sure your students can actually use the information you’ve spent all that time putting into their heads with these helpful tips from teacher and author Paul Wright…

Recall checks

Look at your scheme of learning for a half term. Decide what the key takeaway concepts or vocabulary are at that time.

Design five to eight questions that help students practise retrieving their knowledge on the topic from memory and applying it to answer the question.

Over the six weeks, continue to cover the same five to eight concepts, theories or terms in your questions, but pose the questions in different ways.

Alternative dimensions

Challenge learners’ knowledge security by presenting facts from another dimension and asking them to compare these to ours, stating what the equivalent is in our dimension.

For example, say ‘In this universe, the sky is pink. What colour is it in your universe?’

Learners can select the correct answer from memory (higher challenge). Alternatively, you can scaffold the activity by making it multiple-choice.

Try throwing in some questions where the answer is already correct (ie where something is the same in both dimensions) and see if they notice!

Memorise this…

Prepare a three-slide presentation:

- 1 – show things you want the students to remember

- 2 – black screen with a countdown timer in the centre

- 3 – space for items to be written in or revealed

Explain that the students will be given time to look at the first slide and store the information in their minds, without writing anything down.

When the screen goes black, the timer starts. Pupils must write down as much information as they can remember. When the timer ends, reveal the third slide and ask the learners to share what they’re able to recall.

What stuck?

Stand your learners behind their desks a few minutes before the lesson ends. Tell them that you’ll dismiss each person in turn when they can tell you something that has stuck with them in your lesson.

This challenges their short-term recall and allows you to challenge their ability to express knowledge they have retained succinctly.

Be fair and allow one repeat, but students can’t repeat the same thing as the person who spoke before them.

Using retrieval practice as a revision tool

Science teacher Adam Boxer explains that while retrieval practice isn’t the easiest way to revise, it’s definitely the most effective…

As teachers across the UK become more and more evidence-informed, we’re learning to ditch revision games, posters, highlighting, re-reading and mnemonics.

Instead, we’re replacing these with powerful teaching strategies such as frequent retrieval practice and low-stakes quizzing on core material.

“We’re learning to ditch revision games, posters, highlighting, re-reading and mnemonics”

In fact a paradigm shift is occurring around revision itself. We’ve moved away from a system where we teach a sequence of lessons, have a revision lesson and then a test.

Instead, we’re moving towards a system where we remove the revision lesson and replace it with frequent opportunities for retrieval practice built into the main sequence of lessons.

These changes are possible because of how well-researched retrieval practice is. Cognitive scientists have spent decades investigating its use as a memory technique. Though nothing in science is ever beyond question, the positive results across a vast number of studies certainly seem to suggest it’s an effective method.

Discoveries

There are, however, aspects that you might not be aware of. For example, Hungarian researchers tested whether or not retrieval practice could help mitigate the debilitating cognitive effects of being in a high-stress environment.

Psychologists (and teachers!) have known for a long time that a little bit of stress is a good thing in terms of student performance. However, too much stress can be debilitating and hinder performance.

The researchers found that the power of retrieval practice to prepare students for tests held even when they took the tests under extremely stressful conditions.

Another fascinating finding relates to “participant prediction of recall”. Participants in a study used either re-reading or retrieval practice to learn material, but in varying amounts. After they had a set amount of time with these techniques, they were asked to predict how well they thought they would recall that information in a week or so’s time.

Participants who had done the least amount of retrieval practice thought that they would recall the most. Participants who had done the most amount of retrieval practice thought they would recall the least.

As we can probably guess by this point, the results for the actual test showed the exact opposite. So participants who thought they had learned the least, actually learned the most.

Rich rewards

I think the best way to explain this finding is by thinking about the relative difficulty of the two tasks.

Re-reading is, cognitively speaking, easy to do. Reading is easy. When we re-read material we have a voice in our head saying, “Yes, I got that”, no problem.

But there is a difference between understanding something and committing it to long-term memory.

You can probably understand this article very easily, but if you sat a test on it next week would you remember all, or even most, of its details? Probably not.

“When we re-read material we have a voice in our head saying, “Yes, I got that””

To prepare yourself for such a test you would have to expend serious mental effort. And in the short term, it would certainly feel like you weren’t getting anywhere. It would feel painful, slow, and frustrating.

But what if you did put in that effort, and it worked out? What if you persevered through that short-term pain and feeling of frustration? Imagine you really committed yourself to retrieval practice and were duly rewarded in a test.

What would that feel like?

No doubt, you would probably feel quite proud of yourself. You would start to feel competent in whatever subject you had decided to really commit to.

And psychologists point to competence as an incredibly powerful driver of long term motivation. As we get better at things, we start to enjoy them more.

“In the short term, your students will hate retrieval practice”

In the short term, your students will hate retrieval practice. They will hate not knowing an answer or getting things only partially correct. But the science is clear: it works.

If you can build a culture that looks beyond that short-term pain and understands that it’s worth it in the long term, your students will truly fly.