Caliban from The Tempest – Key quotes explained

Using these lines highlighted by Helen Mears, students can draw intriguing parallels between the stories of master and slave in The Tempest…

- by Helen Mears

- English teacher and British Shakespeare Association education committee member

Unlock the deeper meanings behind Caliban’s powerful lines from The Tempest and transform how students engage with this Shakespeare play…

Who is Caliban from The Tempest?

Caliban from The Tempest by William Shakespeare is Prospero’s put-upon slave. We sometimes think of him as a comic Shakespearean character. However, there is an interesting depth to his story.

In many ways we can see it as mirroring that of Prospero, someone unfairly usurped from a position of power.

Caliban is one of Shakespeare’s code-switchers – veering between the plosive, monosyllabic insults he throws at Prospero and Trinculo, and the beautiful verse he uses when extolling the virtues of ‘his’ island.

This may suggest an inner nobility, while hinting that he’s the island’s rightful ruler.

Is Caliban a victim?

We can see Caliban from The Tempest as a victim because Prospero oppresses and enslaves him when he colonises the island. We can interpret his rebellious behaviour as a response to the loss of his freedom and mistreatment.

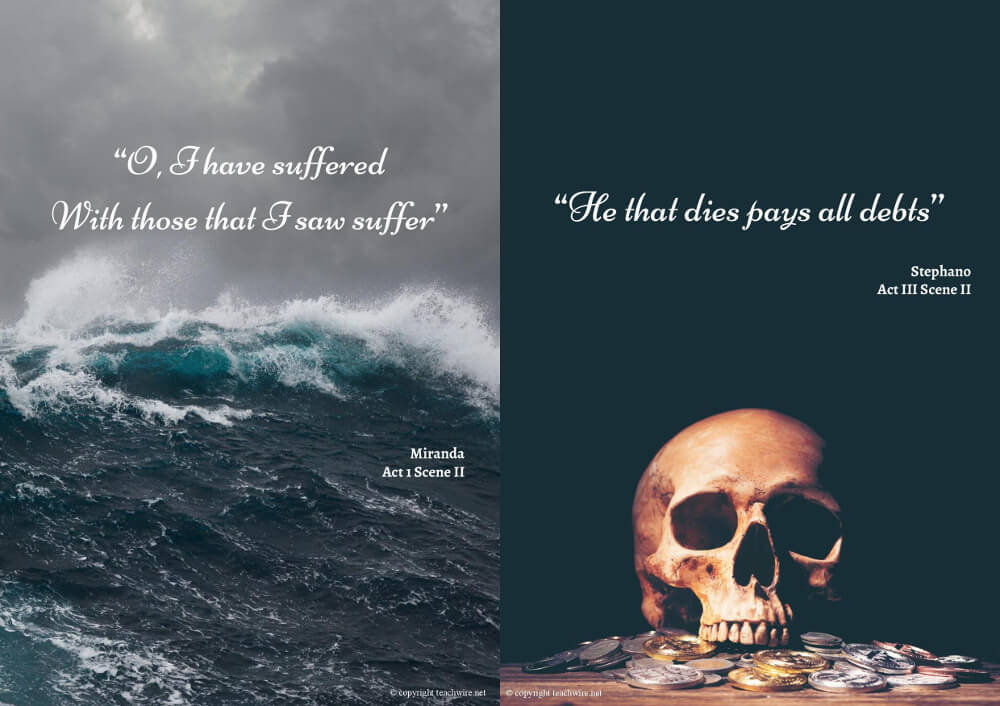

The Tempest teaching resources

Key quote posters and worksheet

This free download contains ten posters featuring key quotes from The Tempest, plus a worksheet with these quotes on for students to make notes on as you read through the play.

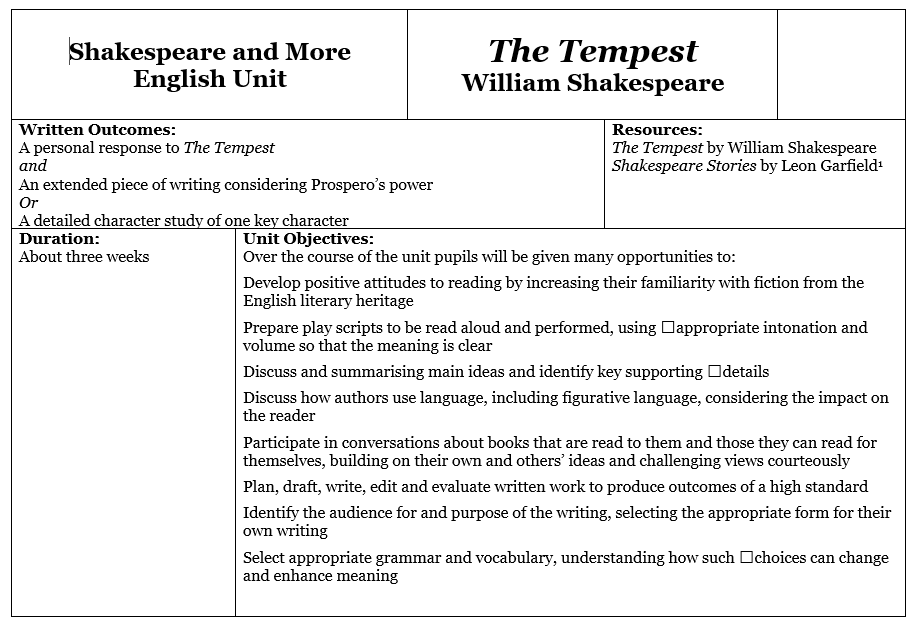

KS2 planning

This free download contains a three-week plan for teaching The Tempest in KS2, with explanatory notes.

Key Caliban quotes from The Tempest

Irony

“This island’s mine by Sycorax my mother,

Which thou tak’st from me.” (Act 1, Scene 2, lines 333-4)

While the play centres around Prospero’s longed-for revenge upon his brother, Antonio, who has usurped him from his position as Duke of Milan, there is an irony to the fact that, having arrived on the island, he himself has displaced Caliban as the lord and master.

Plosive sounds

“All the charms

Of Sycorax, toads, beetles, bats, light on you!” (Act 1, Scene 2, lines 340-1)

This is typical of the angry, insulting language that Caliban uses in talking to Prospero. The hard and plosive sounds of “toads, beetles, bats” reflect the strength of his negative feelings towards the magician and the ill-treatment he receives from him.

Insults

“You taught me language, and my profit on’t

Is I know how to curse.” (Act 1, Scene 2, 363-4)

Caliban expresses his anger at the notion that he has been taught a ‘civilised’ tongue and he uses it only to throw insults at Prospero and Miranda. The irony is that he is also capable of using glorious, poetic language.

Desire for revenge

“These be fine things, and if they be not sprites. That’s a brave god and bears celestial liquor. I will kneel to him.” (Act 2, Scene 2, lines 97-8)

Caliban’s burning desire for revenge is shown by his desperation to align himself with the first humans that he meets. He also briefly slips into prose when he first speaks about them and to them, bringing himself to their linguistic level.

Comic foil

“Hast thou not dropped from heaven?” (Act 2, Scene 2, line 136)

Caliban’s reaction to Stephano and Trinculo is a comic foil to Miranda’s reactions to seeing first Ferdinand and the rest of Alonso’s party towards the end of the play; “I might call him/ A thing divine” (Act 1, Scene 2, lines 418-9).

Parallels

“I say by sorcery he got this isle;

From me he got it. If thy greatness will

Revenge it on him – for I know thou dar’st.” (Act 3, Scene 2, lines 44-6)

This is where Caliban’s comic revenge sub-plot begins to develop. Having made allies of Stephano and Trinculo he now convinces them to assist him in taking revenge for his usurpation.

Although his plot is a parallel to Prospero’s, the native ‘monster’ is punished for his uprising while the titled Prospero is rewarded for turning the tables on those who did to him what he did to Caliban.

As an audience, should we notice this parallel and feel sympathy for the creature that has been enslaved?

Soothing sibilance

“Be not afeard, the isle is full of noises,

Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not…

…that when I waked

I cried to dream again.” (Act 3, Scene 2, lines 124-132)

This oft-quoted speech reveals that Caliban is capable of beautiful expression. He drops his anger and describes the magical qualities of his beloved island.

In place of the harsh plosives of his insults, this speech is filled with soothing sibilance and dreamy long vowel sounds.

His child-like yearning to sleep again to enjoy the beauty of his dreams should also encourage sympathy towards Caliban, who could be viewed as a precursor of Mary Shelley’s maligned and misunderstood noble savage.

Trending

Caliban’s ending

“I’ll be wise hereafter,

And seek for grace.” (Act 5, Scene 1, lines 292-3)

Caliban leaves the play claiming to have learnt a lesson and become wiser. But what happens to him? Does he go to Milan with Prospero or is he left behind, once again the lord of the island?

Which ending does he deserve? How can he be tied into the contextual background of colonisation and slavery?

Caliban may be a low, laughable ‘monster’, but is he a product of nature or nurture? A study of his character can certainly enrich any analysis of the play.

Why you should teach The Tempest

The Tempest is probably Shakespeare’s last solo authored play. It’s traditionally placed amongst the so-called Problem Plays, and therefore hard to pin down to a single genre.

It tells the story of Prospero, who after being usurped as Duke of Milan by his brother now lives with his daughter Miranda on an isolated island peopled by spirits and Caliban – the only indigenous inhabitant.

He has raised a storm that has left his enemies shipwrecked on the island, and at his mercy.

When should I teach it?

The play could be taught in KS3, but as it’s on the list of Shakespeare plays for GCSE English Literature for both AQA and Edexcel, it could also be taught at KS4.

Teaching The Tempest could be a useful precursor to a study of Romeo and Juliet at GCSE, with Miranda and Ferdinand offering a less dangerous take on teenage romance. There are also links to Macbeth in its supernatural elements.

How should I teach it?

At KS3, teaching of the play can focus more on the relationships than the revenge plot. As well as the aforementioned romance, there’s the father and daughter relationship (a recurring feature of the Problem Plays) between Prospero and Miranda.

This can be interesting to explore – particularly for how Prospero engineers her meetings with Ferdinand as part of his grand plan.

Then there are the master/servant relationships Prospero has with Caliban and the spirit Ariel. There’s much to explore in the exchanges Prospero has with these characters, particularly the ways in which he trades insults with Caliban.

For GCSE students, the revenge plot is a good starting point. It highlights the dichotomy between revenge and forgiveness. It also allows for deeper examination of the parallels between Prospero and Caliban.

We are encouraged to sympathise with Prospero for having been usurped by his brother Antonio, and yet Prospero has himself usurped Caliban as ‘ruler’ of the island.

Why should I teach The Tempest?

Our post-Covid world could potentially give our students a greater understanding of isolation and how it might feel for Prospero and Miranda, trapped as they are on the island.

Studying The Tempest also provides excellent opportunities to study historical performance practices. Written late in Shakespeare’s career, the play was likely intended for performance at the indoor Blackfriars Theatre, which Shakespeare’s Acting Troupe acquired in 1609.

His later plays reflect this change of location, with more intimate staging and a greater use of music and song. The Tempest is one of a few plays in the First Folio to feature contemporary stage directions by the company’s scribe.

How does it link to the rest of the curriculum?

A study of The Tempest will have strong links to history, PSHE and current affairs. Prospero’s reign over the island and displacement of its sole indigenous inhabitant links with issues of colonialism – both at the time it was written and to more recent history.

It raises questions around identity and the master/slave dynamic.

Is Caliban justified in his revenge plot, merely wanting to take back the land he feels was stolen from him? These questions of identity can lead to discussions concerning the Black Lives Matter movement and its resurgence following the murder of George Floyd.

How can I watch it?

The play is frequently performed, and both The Globe and The RSC have recent productions available on DVD. For an introduction for younger students, there’s a CBeebies version.

You can also try the ever-popular Animated Tales version.

Helen Mears is an English teacher who sits on the education committee of the British Shakespeare Association. Follow her on Twitter at @shakesmears. Browse more resources for Shakespeare Week.