The Story of the Nile – History and geography for Key Stage 2

The rich history of Egypt is inseparable from its geographical relationship to the world’s longest river – it’s not all mummies and pharaohs

“The history of good farming land is the history of the world.” One of the most spectacular pieces of natural evidence in support of this notion is the link between Egypt and the River Nile. If you look at satellite images of the country taken during the day you’ll see an arm of green running north through the surrounding desert, up towards the Mediterranean where it fans out at the delta. By night, you’ll see the electric lights of modern civilisation illuminating the whole thing. The banks of the Nile and its delta have provided most Egyptians with a place to live, from 4,000 years ago to present day.

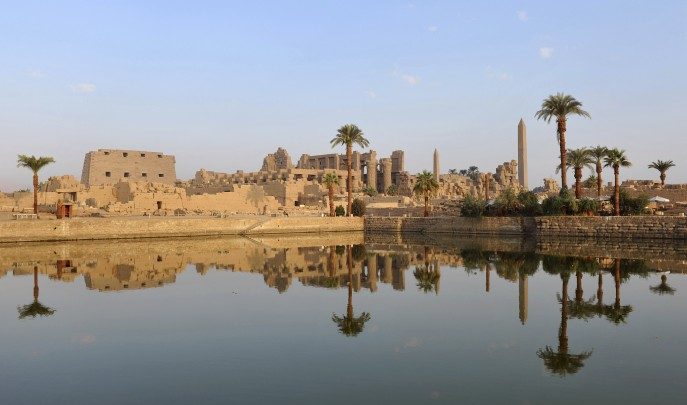

Ancient Egypt, by far the most popular choice for the KS2 history ‘ancient civilisation’ option, has a fascinating history of culture, technology and warfare, and it’s a history that’s inseparable from the country’s geography. The nation’s entire wealth – which allows a rich ruling class to develop – depends solely on the Nile. The annual floods bring down silt and water into the narrow strips of land each side of the river, fertilising the earth. No floods means drought, which means starvation. Something that, sadly, has been clearly illustrated throughout Egyptian history. The country has seen dramatic historical and geographical changes in the past, as well as in more recent times. While the Egyptian civilisation we typically study only begins to appear around 3500 BC, recent information suggests the first Egyptians appeared in a savannah grassland environment. There’s evidence of cattle, giraffes and other grassland species living in areas that are now desert, due to rain patterns starting to shift around 5000 BC. This made the Nile and its floods even more vital. Records also suggest that just over four millennia ago the region was hit by a drought that spanned several decades, leading to the end of the Old Kingdom (circa 2686 BC-circa 2181 BC). (Some sources even suggest that people were forced to measures as extreme as eating their own children.) Events like these are ideal for helping pupils understand why climate matters so much, and how biomes and vegetation belts are in constant change, in turn affecting land use and human development. While Ofsted is placing ever more emphasis on subjects and subject knowledge rather than topic work, topics can still be of great use – as long as the subject learning objectives are clearly highlighted within them. A study of Ancient Egypt is the perfect way to show that historical and geographical knowledge and skills can supplement each other, extending learning and understanding in both subjects, and here’s how.

Building knowledge

First, try to find out which crops were grown by Ancient Egyptians, and which are grown today. A trip round a local supermarket might find potatoes from Egypt and, at certain times of the year, various fruit and vegetables. Are the ‘food miles’ involved getting them here any different from Ancient Egypt selling grain to countries around the Mediterranean Sea? What technology did the Ancient Egyptians develop to lift water from the Nile into their fields? Who invented the shaduf and when? Is it still used today? We know Egyptians used mass labour to build pyramids and temples; did they also work together to build irrigation channels and drainage ditches? That requires a lot of coordination. Who organised this? And what does that tell us about Ancient Egypt? When were the first Suez canals built? (Some sources suggest around 1900 BC. The modern canal was opened in 1869 AD). History is often as much about continuity, and repeating patterns, as it is about change and ‘progress’. If we look at transport, we’ll see much of Egypt’s wealth has always come from trading goods with the Mediterranean world, but also upriver, further south into Africa. The natural flow of the current aids travel to the mouth of the river and the sea, and the prevailing winds help sail boats return upstream. So the Nile is doubly important – as a source of water for agriculture and as a route for trade.

Contexts for learning

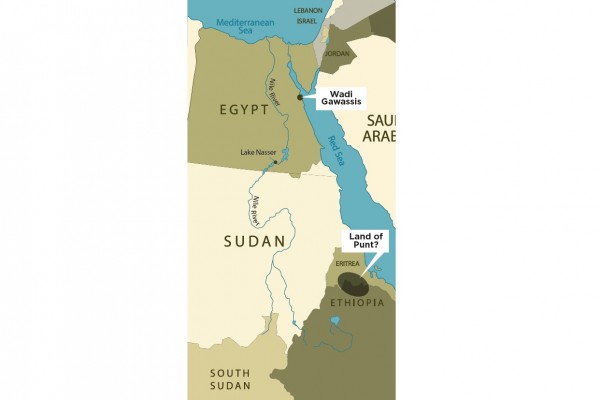

Any study of Ancient Egypt really does start with the River Nile. Where does the Nile rise? Where does it end? Which countries does it flow through? This gives us a link into discovering the names and locations of major countries, rivers and cities – even Khartoum and Lake Victoria: a focus for our locational knowledge. By the end of Key Stage 2, pupils are expected to know the names and location of major countries, cities, mountains and rivers. Where else in the curriculum might they get the opportunity to do this for Africa? If we use the great female pharaoh Hatshepsut and her expedition to Punt around 1473 BC (see map, below) we have a context in which to study the geography of the region, as well as the history.

No-one knows where Punt was, but most historians think it was in Ethiopia or Eritrea. Some think it was Yemen or Arabia. No-one is absolutely sure. We do know that it had goods the Egyptians wanted – ebony and ivory, leopard skins and ostrich feathers from the African interior; and frankincense and myrrh, cinnamon, baboons and monkeys from Punt. Myrrh was very important for incense, for temple rituals. One expedition to Punt is said to have brought back 20,000 bundles of myrrh. Monkeys were important too – Egyptian farmers trained monkeys to climb trees and throw ripe fruit down to them! Egypt exchanged these goods for gold, papyrus, linen, grain, and glass. It was a lucrative business. By starting with Egypt’s geography and moving on to its history, or interlacing the two, both the history of Ancient Egypt and the geography of Africa and the Mediterranean are studied in context, and enriched. Egypt doesn’t solely have to be about pyramids, pharoahs and mummies – most people were (and many still are) farmers, whose prosperity depends on the Nile and its flooding. There are some great opportunities here for cross-curricular planning, and for enquiries that enhance meaning without taking us away from learning outcomes which are explicitly geographical or explicitly historical.

Go with the flow

Following the Nile’s story from the ancient to modern world… We might also look at contemporary issues about dam-building in the upper Nile, which takes us into physical and human processes. We know the Nile was critical for Ancient Egypt, but which countries use the water today – for irrigation, for hydroelectric power and for transport? Why does it, and other rivers for that matter, flood? Why does it flood in the summer? How long does it take rainfall in the mountains in the interior of Africa to travel downriver to Egypt? What is the link between rainfall and river flow? And why does the Nile not flood as much today? What have people done to limit floods: are there lessons there for flood defences in Britain?

Ben Ballin is a primary geography and global learning consultant, and co-author of The Mediterranean for the RGS-IBG. Alf Wilkinson is a freelance consultant and former history teacher. He is a member of the Historical Association’s primary committee.