Barry Smith – How Great Yarmouth Charter Academy was turned around

“We’re not miracle workers” says Barry Smith, head of Great Yarmouth Charter Academy; but there are quite a few people, including an Ofsted inspector or two, who would disagree, discovers Helen Mulley…

- by Helen Mulley

- Former editor of Teach Secondary magazine and award-winning podcast host

“I’d advise arriving at 8.15 if possible. It’s when the magic happens!”

I have to confess, my heart wasn’t filled with delight to read this in an email from Barry Smith, head of Great Yarmouth Charter Academy, a few days before I was due to visit his school.

It meant a pre-5am alarm call – but needs must, and so my photographer and I filled our largest travel cups with coffee and made it to the seaside with enough time for a brisk and breezy walk to the water’s edge and back again before presenting ourselves at the academy’s front desk.

All quiet

Even its mother would have to agree that, at first sight, Charter Academy is not the most prepossessing of environments.

Forget fancy, modern glass buildings, shiny logos and cleverly curved staircases – what you get at Barry Smith’s place are boxy classrooms and corridors that have seen many decades of learning, on a site that’s the tighter side of compact (although there’s an impressive-looking new science block currently under construction).

The reception area is functional, and our welcome from the people working there was friendly and helpful… but it was all rather quiet, and even a little bit dull. Where was the magic we’d been promised?

And then a door swung open and Barry Smith walked in. And it began.

“If you don’t like it, there are other schools. You’re not obliged to send your kids here. But if you want them to be looked after, if you want them to be safe, to learn lots and to leave with a good set of results… that’s what we do.”

Barry Smith, headteacher

Meeting Barry Smith

Instantly flooding the space with his presence, and greeting us with a warm, broad Tyneside accent, the headteacher grasped my hand for a wince-inducing shake, before proceeding to take us – at a breakneck pace that we quickly realised was his standard speed of travel – through to where the kids were starting to arrive for a standard Thursday at Great Yarmouth Charter Academy.

“Good morning, sir!” he bellowed cheerfully at the first student we passed – a lanky lad who looked about 15 and should by rights, therefore, have responded in a mumble, chin buried in his chest.

Instead, the teen grinned, and belted out another “Good morning, sir!”, meeting Barry Smith’s outstretched hand with his own, before adding, for our benefit, “Good morning miss, sir; welcome to Charter!”

Chanting Flanders Fields

This exchange was repeated multiple times with a succession of youngsters of all ages as we made our way towards the main hall. Sometimes there would be friendly teasing; other learners were encouraged to straighten ties, or tuck a shirt in more neatly.

One young lady with suspiciously dusky eyelashes was sent to “ask miss for a wet wipe”. And a gaggle of Y7 boys, at Barry Smith’s instruction, chanted In Flanders Fields. Word perfectly. Twice.

“Um, does this happen every morning?” I asked a diminutive Y8 girl wearing an ‘Ambassador’ badge on the lapel of her blazer, while Barry was busy coaxing a smile out of one of her classmates who had arrived with slightly shadowed eyes.

“Yes, miss,” she said, very seriously. “He’s always here.”

Following an exuberant KS3 assembly (more chanting of In Flanders Fields, led from the front by Barry, followed by a rousing rendition of Invictus), and another for KS4 females, in which Barry lectured them off the cuff and with respectful humour for a good 10 minutes or so about the importance of self-belief, hard work and ‘no silly hair extensions’, it was time for lessons to begin.

Call and response

Teaching at Charter is delivered according to a consistent and clearly outlined set of methods. There is no group work; no role play. And, thanks to the ubiquitous use of SLANT (see panel at end of article), along with a minutely managed behaviour policy, no straying off-task for anyone.

I watched an English class, for example, where Y7s were being introduced to A Christmas Carol. “Social criticism is a genre that highlight’s s- p-”, the teacher called out.

Several hands shot up, dead straight, and he chose a pupil to give the answer, which she did, correctly. Then he asked the question again, choosing a different hand. And then again, picking a random pupil without asking for hands. And again, getting the whole class to respond.

“Social criticism is a genre that highlights society’s problems, sir!” they chanted, in unison.

“Sir?” interjected Barry Smith from the doorway. “Could we say, ‘societal problems’, perhaps? Might that sound even better?” Of course, it did.

Swift improvement

“If a school’s going to succeed, there are only two things that matter,” Barry tells me later as we sit in an empty classroom (he hates being in his office, and avoids it at all costs). “Improve teaching, and improve pupil buy-in.

And if you improve teaching, you will improve pupil buy in. Because that’s what you want – classrooms where kids come in, and every lesson they go, ‘I’m good at this’. They leave feeling accomplished.”

Back in 2017, no one would have described Great Yarmouth Charter Academy as a school that was succeeding. Results were through the floor; behaviour was feral; teachers were terrified.

Eventually, the academy was handed over to the Inspiration Trust, whose CEO, Rachel De Souza, tempted Barry Smith away from the already thriving, if somewhat controversial, Michaela Community School – which he had helped to set up three years earlier – to lead it.

Transformed

“I never wanted to be a headteacher in my entire life,” he insists. “I told them, ‘All I know is what really good teaching is, and what really good behaviour is. That’s all I’m interested in. If you let me do that, I’ll do it.’ And they did. As a consequence, the school transformed within a matter of days. Kids who were hiding under the furniture to be safe, are now thriving and flourishing. It’s a lovely, happy school. Staff who were dreading coming to work now love being here.”

Sure enough, everywhere I go in the school, I see evidence of contented children, keen to learn. They are confident and friendly; they look me in the eye and speak clearly.

Students tell me repeatedly how there is no bullying here. And the older students, as well as the staff, consistently confirm what Barry says about the state of the place before he took over.

Indeed, the Ofsted inspector who led a no-notice inspection following a spate of media reports about the ‘harsh’ discipline policies at the school, and who was a local chap, described the transformation at the time as ‘miraculous’.

Hard lines

“What we focus on is building a culture of genuine mutual respect,” Barry says. “That means teachers are respected, as well as pupils. All it takes is a leader who has a vision, and is prepared to stick to that vision. We have to be warm and strict. It’s hard to be warm when you’re frightened; our teachers aren’t frightened of the children any more. So they can be warm.”

When I ask about inclusivity, mindful that a FOI request has revealed that over 80 children were removed from Charter’s roll in the first 18 months of the new regime – although in fairness, over the same period, the Y7 intake leapt from 115 to 175 – Barry is clear that the school’s aim is, and has always been, to work for everyone.

“Our grades doubled in the first year,” he points out, “and we’ve just had four kids get 8s and 9s and full scholarships to a local private school – that wouldn’t have happened before.

‘We do loads for those who have EAL, literacy and numeracy needs, SEND. But most of all, we create a culture that’s safe and warm and kind and supportive, and incredibly inclusive.

‘You can’t do much more than that, as an ordinary classroom teacher. We’re not miracle workers, no school is – but we permanently exclude very, very few kids. We do everything we can to keep them in.”

Beyond the headlines

There’s no doubt that Charter Academy is a special place. In fact, I’d go so far as to say it’s like no other secondary school I’ve visited.

And as we left, the sight of a playground full of students, all making their way back to classrooms carrying identical, Charter-branded bags in their right hand, struck me as a perfect illustration of how Barry really managed his ‘miracle’ in Great Yarmouth.

Rules about not only what kind of bag is allowed, but how it must be carried, are what make headlines, with outraged commentators claiming children are being subjected to draconian and unnecessary discipline.

But the truth is, when he arrived, Barry Smith walked into a school where there would regularly be vicious fights over who had the best accessories.

Knocked over

Moreover, smaller pupils (and teachers, for that matter), were regularly being bruised, scratched and even knocked over by bulky rucksacks worn on the backs of clumsy or careless young people, who hadn’t ever been encouraged to think about others as they made their way between classrooms.

Clearly, to address both issues, students needed to learn respect for the possessions and personal space of others, as well as not to judge anyone, including themselves, on the basis of what brands they wear or carry.

You don’t get that shift of culture in a matter of days; but in the meantime, what you can do, is remove the non-human variable that’s contributing to the undesirable behaviour.

With uniform bags, carried in the hand, suddenly, no one is in danger either of being bashed into, or mocked for owning a low-status tote. And that makes it so much easier to work on, and model, the bigger, deeper stuff.

Which – and I defy anyone to deny it – is what really matters to Barry Smith, and what is really changing at Charter.

Pupil voice

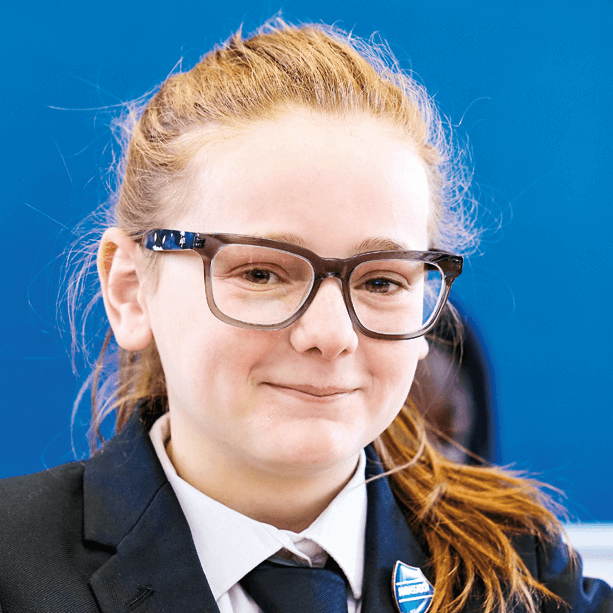

Honey Fox, Y8

“I went to three different primary schools, because of bullying. I got quite behind in maths, because I missed a lot of lessons having to speak to teachers about what was happening. Here, though, there isn’t any bullying. If anything happens, we know we can tell, and it will be sorted, probably within the same day. I speak to my friends, who went to other secondary schools, and their schools aren’t like this one. My favourite subject is PE, which is good, because it fits with the job I want to do. I want to join the police force; probably as a dog handler.”

3 changes that have worked for Charter

- SLANT

A strategy outlined in Teach Like a Champion, by Doug Lemov, the acronym stands for: Sit up; Listen; Answer Questions; Never interrupt; Track the speaker. It’s standard classroom practice at Charter, for all ages, and makes for a learning atmosphere that is calm, focused and orderly, yet has plenty of space for lively interaction and personality. - Sir/miss

Everyone at Charter uses this language to address each other. Teachers to students; children to adults; learners to each other. It’s part of the culture of mutual respect that is crucial to Barry Smith’s vision. - Learning by heart

A poetry pamphlet is given to all students on arrival, and they are expected to learn the contents by heart. Teachers do, too. Learners are regularly encouraged to chant the poems, especially at morning assemblies. It’s partly about cultural capital, partly about the promotion of retention and recall – a feature of all Charter teaching.