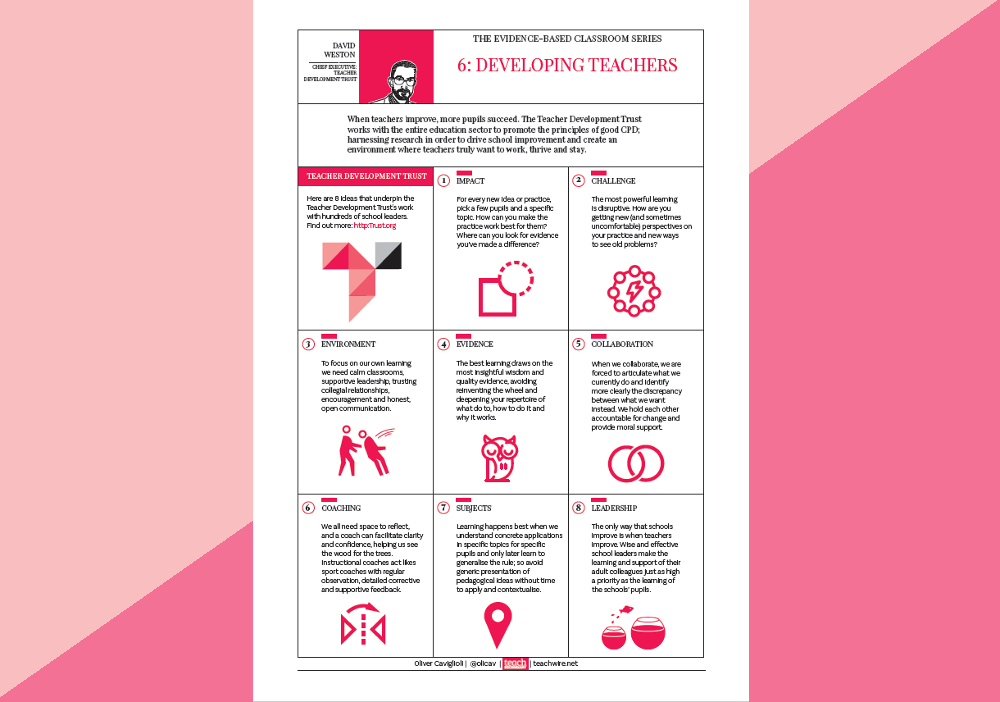

CPD for teachers – How to successfully unlock its power

Explore real CPD challenges and read expert advice from practising teachers about how to get the most out of your professional development…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

When it comes to CPD for teachers, there are lots of strategies you can try to enhance colleagues’ teaching skills and help them advance their careers…

Involve staff in the setting of development objectives

As expectations around CPD for teachers continue to evolve, Denise Inwood looks at how schools can adopt a more collaborative approach to their staff development…

Schools are rapidly moving away from one-off annual performance reviews linked to data-informed objectives, and towards a much more supportive and developmental approach.

This prompts the question – what can be done to give teachers more ownership of their professional development, and become more actively involved in how it’s planned?

Maintaining an ongoing dialogue throughout the year between a teacher and an assigned reviewer is one option that will likely result in a positive change to how teachers view their CPD – so how can you get the most out of it?

1. Tailor CPD to both teachers and the wider school

Teachers should begin by thinking about their existing experience, knowledge and needs. Are there any current or persistent challenges they wish to address? Anything that impacts upon their work on a daily basis? How might overcoming these challenges connect to their longer term career objectives?

Teachers should carefully consider how their personal objectives align to whole school plans. Ideally, professional development will connect teachers’ individual professional needs with wider school priorities, making this an important point to raise in discussions with their reviewer.

2. Ensure objectives are clear

Much has been written on how to set particular development objectives. The acronym ‘SMART’ largely captures the best advice, in that these objectives should be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Time-focused. In this way, professional development objectives can be presented with greater clarity and clearer success criteria, making them easier to review at a later stage.

3. Set achievable goals

Good CPD for teachers should reflect the different ways in which we grow and develop professionally on a day by day basis. Teachers should set aside time for regular check-ins with their reviewer throughout the year. Break up long-term goals – which can seem daunting – into smaller, more incremental milestones that are achievable and valuable in and of themselves.

4. Understand the impact

Teachers should look to capture evidence of their professional learning and reflect on how it has impacted upon their teaching practice. A teacher should regularly review their development objectives and progress towards attaining them – just as they would with a student in their class.

Be aware that ‘professional development’ doesn’t necessarily always equate to formal qualifications or external training; it could just as easily involve reading articles, having discussions with colleagues or observing lessons.

Denise Inwood is founder and CEO of BlueSky Education – an online platform used by teachers in more than 40 countries worldwide, to enable them to support their professional learning and objectives and link them to a school’s strategic goals. Find out more at blueskyeducation.co.uk.

How to create powerful teams

The key to your school’s success may be right in front of you, says deputy headteacher Sam Crome…

We invest tremendous amounts of effort and resource into creating the best schools and workplaces that we can. Thousands of hours are spent on curriculum planning, continuing professional development, and pedagogical understanding. These are worthy uses of our time.

But what if we’ve been missing a vital component of improvement and purpose? What if something we do already, many times a half term, is being underutilised?

Every school is full of teams. They have different functions, meet at different intervals, and have the potential to be improved in numerous ways. We can turbocharge huge aspects of school life by helping our staff teams to thrive together.

Key principles of teaming

There are many principles of teaming that we know can contribute to high-performing, thriving teams. In my experience, some of the most applicable and well-evidenced are:

- A clear, shared vision, purpose, and set of values

- High levels of belonging, psychological safety, and trust

- Ambitious, clear team goals

- Crystal-clear role clarity, mental models, and systems

- A culture of evaluation and debriefing

- Commitment to learning and development

Of course these could sound idealistic, and somewhat divorced from the hectic reality of primary schools. After all, staff are members of many teams, and have few opportunities to contribute to them beyond their allocated meeting time. The good news, though, is that small teams making small changes can create impressive results.

So, let’s turn our attention to how primary school teams can practically harness their potential, even amidst packed schedules and teachers wearing many hats.

Communication

Thriving teams agree how they will communicate, and codify this for both convenience and clarity. When, and how often, does the team leader send out communications? Does the team use email for discussion and queries, or is a shared system, such as those found on Microsoft or Google packages, the best place to communicate?

Infrastructure and resources

The team should ensure that all resources are easy to find, relevant for their work, are high quality, and are centralised to the point where it reduces workload and allows members to stay on track with their core work (with room to adapt, if required).

Collaborative planning time and an agreed approach to centralisation can improve the team’s resources, cohesion, and the quality of learning and teaching.

Learning

The best teams learn together; they view one of their core functions as being to grow and improve as a group. This permeates the way they meet, their CPD programme, and the way they help each other in day-to-day interactions through using a coaching approach and exhibiting helpful behaviours.

Learning as a team improves expertise, which in turn improves processes, but, beyond that, it helps bind the team together in a powerful shared experience. Team debriefing can have a 20 to 25 per cent improvement on team effectiveness, so team learning opportunities should involve reviewing processes.

Meetings

In a small team, you might only get one chance of a meeting per half term, or even term. The agenda needs to be shared in advance, and the items should link to the team’s core purpose and mission.

Try to get admin and most logistical items covered out of the meeting time, so that meetings can be used for meaningful discussion, sharing of expertise, and collaborative work.

Follow up the meeting with actions and resources, so that ongoing work is frictionless until the next meeting. Every minute counts for team meetings.

Following these four measures of teamwork will result in your team making the most of its time together, with clear methods of working, clarity over communication, and purposeful meetings that are packed with learning and discussion.

There is plenty more that can be done, but this foundation will help your primary teams begin to build into cohesive groups who embrace coming together, and get fantastic results.

Sam Crome is a school leader, currently a deputy headteacher and director of education for a multi-academy trust in Surrey. His book The Power of Teams: How to create and lead thriving school teams is out now.

Share your CPD with an inter-school partnership

Thomas Forbes looks at what we can gain when teachers and leaders start thinking more creatively about their inter-school partnerships…

Whether united by being in the same MAT or not, different schools in the same area can stand to learn a lot from how their counterparts operate.

Sometimes, however, the idea of sharing practice between schools can be contentious. If the benefits are generally widely accepted, why the hesitancy?

Well, the reality is that as organisations – and even as individuals – we can be (rightly) wary regarding the ownership of ideas and wider questions concerning intellectual property. The process of inter-school collaboration can itself be logistically daunting.

So what would a truly effective method of sharing practice look like?

An ongoing process

Any serious programme of school improvement should involve at least some element of visiting other schools to see how certain things are ‘done’.

The profession can be broadly accepting of this, especially when seeking to address particular behaviours, or in response to feedback from reviews.

And that’s often as far as it goes. Any notions of sharing and disseminating best practice more generally, in a systematic, long-term way, tend to fade once a solution to that specific problem is found. Which is a tremendous shame.

Encouraging teachers to talk to and learn from each other is arguably one of the most effective and expedient ways there is of developing practice.

“Any serious programme of school improvement should involve at least some element of visiting other schools to see how certain things are ‘done’”

Inter-school training and collaboration therefore can, and should be a key tenet of the reflective process. This is for both schools and individuals.

In fact, there’s a strong case to be made for inter-school training to occupy a meaningful place within school/teacher development and ongoing quality assurance. This is even when there isn’t a specific ‘problem’ to respond to.

Sharing best practice through inter-school training can, after all, present opportunities for improvement and development that might not have even occurred to leaders and staff otherwise.

Embracing this ‘inter-school training’ philosophy can unlock new systems and new ways of thinking – so how can we get there?

Step 1: Personal development days

The operational demands of school life can frequently result in ‘professional development days’ becoming less about development and more about administration.

One tried and tested way of resolving this is to set aside a dedicated PD day for everyone. On this one day, all staff can have the opportunity to go elsewhere and investigate something they feel is going to help them.

This does mean everyone, from SLT down to support staff. My school scheduled a day like this in the middle of a term, right when most other schools would have been having ‘normal’ days. This was to maximise the chances for colleagues to arrange impactful visits to other schools.

Logistically, it will be necessary to allow enough time beforehand for colleagues to arrange school visits that are right for them.

In our case, the subsequent value of this for staff was enormous. Almost everybody returned full of new ideas and solutions for old problems. They’d also established robust foundations for future inter-school training partnerships.

Step 2: Peer review

Moving away from ad hoc arrangements, we’ve seen great value in establishing more formalised peer review support networks involving three or more participants.

These work from the principal down. They can provide regular opportunities for colleagues in the same roles across different schools to swap their insights and expertise, and act as critical friends.

Some LAs have facilitated area-wide peer review systems. However, there’s nothing to stop schools (or indeed individuals) from establishing similar networks themselves. The value they offer is in the sharing of strategy and identifying of patterns. They also help you contextualise what’s taking place within your own school.

These two initial steps can act as a springboard for establishing a culture of openness and shared reflective practice. This can then play a pivotal role in improving both your school’s CPD provision and student outcomes.

Thomas Forbes is a head of history based in the East of England

Don’t overlook the importance of subject-specific training

General purpose CPD for teachers is all well and good. However, don’t neglect the training your staff need to become subject experts, says Daniel Harvey…

Continuing professional development is essential for helping schools and teachers to close the disadvantage gap and ensure that the quality of teaching remains high in the service of student outcomes.

There’s plenty of evidence to show that teachers’ subject knowledge and standard of pedagogy can have a significant positive impact on students’ progress, including the findings of a 2014 paper, ‘What makes great teaching?’.

We need to make teachers and trust and school leaders at all levels aware of those proven practices and processes that will ensure time invested in professional development and practice improvement pays off.

Subject demands

Of course, you can only set aside so much time for professional learning and development. This means that any planned work in this area has to justify the time and resource investment.

Complicating this are many potential pitfalls and barriers to realising improved classroom practice. Time pressures and assessment demands are liable to derail even the most carefully thought-through plans.

School leaders must strike a balance between fulfilling school priorities and providing subject leaders and their teams with sufficient time to improve their planned and taught curriculums.

If senior leaders are using regular curriculum reviews to support curriculum investment, we must afford subject leads the time and resources needed to address those aspects of teaching that will most directly impact students’ standards.

If students are to become experts in their school studies, then their teachers will need to be the very best subject experts.

This won’t happen by accident. Rather, it happens via a careful understanding of the needs of the taught curriculum, and the teachers who are actually teaching it.

Outside influences

Sometimes, there can be the need for some large-scale curriculum change. This might be due to the introduction of a new subject topic, or some change in the way that you need to teach disciplinary knowledge henceforth.

Two illustrative examples from my own subject of science would include, firstly, the introduction of nuclear magnetic resonance in A Level chemistry several years ago. Then there were the changes to how we assess practical work at GCSE level, and what we’d previously called ‘How Science Works.’

Another external influence can be exam/assessment demands and reforms. Almost without fail, some detail related to external exams or assessment will bring about the need for staff to have the appropriate knowledge explained to them by an expert source.

At the same time, they need to understand precisely what these changes are likely to entail for their teaching and planned curriculum years hence.

Secondary teachers can, and should be ready to expect changes in subject specification (though I’m old enough to remember when we would talk about the ‘syllabus’). This will nearly always be accompanied by amends to the assessment that will require informed changes to the curriculum.

Incoming knowledge

Subjects are always evolving. We need to learn and development so we can invest this knowledge into the curriculum. This enables teachers to stay refreshed and connected to their subject. This is how subjects remain relevant.

One subject teacher I know is fond of saying, “The planned and taught curriculum are never finished.” We must invest time in planning and modelling the curriculum. This is so that students can benefit from the very best teaching provided by teachers who are secure in what they’re doing and why (as set out in the aforementioned 2014 white paper).

CPD for teachers can also assume huge importance when staff take on different roles within the taught curriculum. An example of this might be a Y4 teacher moving up to teach Y6 for the first time. Or you might be a secondary teacher stepping up to teach A Level.

When faced with such changes, it’s incumbent upon leaders to ensure that the successors in each instance possess sufficient training and prior development to capably model the new taught curriculum. This is so that students continue to receive the best possible instruction.

External expertise

I’ve been fortunate enough to benefit from external expertise that my department was able to source. I’m a science teacher, and my main expert area is chemistry. However, I’ve spent time working alongside other chemists and biologists to teach the combined science GCSE.

It’s a qualification that requires students to study all three science domains. However, there was a point at which our student outcomes and question level analysis showed weaknesses in students’ work in physics.

Working alongside the Institute of Physics for a sustained period on improving both my own knowledge of concepts such as energy and forces, as well as how best to teach the discipline, eventually resulted in confidence boosts for both myself and my colleagues. We had a more informed approach to our teaching of models based on effective practice.

The below criteria can help you when deciding whether or not to use an external provider of CPD for teachers:

- Is the external provider an expert within their field, and if so, what are their qualifications?

- Can they successfully oversee a process that will apply what they know to the aim of achieving your school’s desired outcomes improvements in practice?

- Does the provider have a past track record of success (especially in similar school contexts)?

- Will the provider be able to cite relevant and robust evidence to back up their guidance?

- Can they provide ongoing support throughout the plan’s implementation?

- Are there any superior alternatives to what the external provider is offering?

Your annual CPD calendar

The best time to embark on your curriculum development planning for the following year is during the month of June. Some schools will task heads of department with reviewing existing plans and provisions. They’ll then identify areas for improvement and devise plans to address these areas.

They’ll subsequently share these reviews with school leaders. This is so that they can plan the following year’s CPD for teachers in a way that balances whole school objectives with subject priorities.

Needless to say, the exam results the school receives during August will need to be carefully assessed and factored in. This is because these may necessitate changes to the plan due to emerging academic priorities.

Ultimately, the undertaking of CPD is a hugely important part of what it means to be a good teacher. Aside from the obvious benefits of improved practice and outcomes, it’s also the case that teachers can and do enjoy being engaged by good quality practice that’s relevant to their role.

Those colleagues within the school who are tasked with planning and leading on CPD for teachers should be mindful that there is an enormous body of evidence out there that supports the implementation of individual team plans. It shows how CPD leads need to attend to the process throughout.

Their role is to set the conditions needed for the CPD to work, and for the progress made by colleagues to be reinforced.

Take it further

- The EEF has produced a concise evidence summary for teachers and school leaders. This explains what’s needed for CPD for teachers to result in new and effective practice

- Thomas Guskey has been researching the field of CPD for decades. His essay ‘Gauge impact with 5 levels of data’ serves as a good introduction to his findings.

- Philippa Cordingley is one of the UK’s leading CPD researchers. She is able to offer plenty of advice on what school leaders should know about leading and implementing effective CPD.

- Subject associations can provide cost-effective ways of implementing subject-specific CPD for teachers. They offer considerable help and expertise to teams that have been tasked with implementing a CPD development plan.

Daniel Harvey is a GCSE and A Level science teacher. He is also lead on behaviour, pastoral and school culture at an inner city academy.

Go back to basics with DRIVE

Ed Carlin believes the profession should zero in on the fundamentals of teaching and learning – and has just the tool to help…

Imagine the following scenario. While out on his latest driving lesson, little Liam is getting increasingly frustrated.

His instructor’s a really nice guy, often sharing stories that make Liam’s driving lessons all the more interesting and memorable. The trouble is, it’s now Liam’s third lesson with Mr Stevenson, and he still doesn’t understand how to engage the clutch.

Liam desperately looks to Mr Stevenson to ask for instruction. Sadly, he’s met with yet another pearl of wisdom from his guide: “Liam, learning to use a clutch is a bit like music. Pedal in and pedal out, all in harmony with the beat. Rhythm, Liam my boy! Rhythm…”

By now, Liam’s sat through dozens of stories, anecdotes and observations, while Mr Stevenson seems to have lost all sense of purpose. Liam is 55 quid down, yet barely able to back out of driveways. Still, ask him about Mr Stevenson’s holiday to Cyprus, and he could probably give you a blow-by-blow account…

Getting from A to B

Our students depend on us to utilise our expertise, knowledge and agency to deliver the best possible learning experiences and outcomes, because they know only too well that there’s an endpoint. Irrespective of whatever the latest learning trends are, their learning journey will inevitably end with some form of assessment or test.

Returning to Liam, he has enough money to cover 10 lessons with Mr Stevenson. He’s anxious about the driving test he’ll sit in a matter of weeks, and has lost all faith in his teacher. The highly knowledgeable Mr Stevenson will doubtless continue to be pleasant company – yet he simply can’t teach, due to him having no concept of planning, implementation and practice. Liam will fail his test. It won’t be his fault.

It’s my belief that we’re wasting far too much time in our schools promoting the notional advantages of rapport, personality and entertainment.

Yes, we must foster authentic and meaningful relationships with the students in our care. However, in my experience, the very best relationships are built on students having faith in their teachers to get them from point A to point B successfully. That’s sustainable rapport.

Introducing DRIVE

Let me therefore introduce you to DRIVE – a creation of mine several years in the making which, at first glance, may seem at odds with the profession’s current trajectory.

DRIVE is a learning and teaching programme that’s all about stripping things back, and restoring a lost sense of purpose to our classrooms.

As we desperately claw at imaginative learning activities, and spend ever more time on ‘getting to know our students’, we move further away from the job at hand – that of teaching excellent lessons, every time. Mr Stevenson had 10 lessons to get Liam through. If Liam was your child, how would you want each minute of those remaining lessons to be spent?

Even the most experienced practising teachers need training from time to time. Hence the existence of career-long professional learning which – if it’s to be successful, at least – will have learning and teaching at its core.

That’s where DRIVE comes in. It’s a structured framework, designed to improve the quality of teaching and learning within a school, that’s built around five key components – Development, Research, Impact, Validate, and Evaluate. Each one plays a crucial role in enhancing both the educational experience for students, and professional development processes for teaching staff.

How it works

Let’s drill down into each element, with illustrative examples of how the programme can be put into action.

1. Development

(Lesson planning and observation cycle)

Teachers engage in a continuous cycle of lesson planning, delivery and observation. This includes creating detailed lesson plans with clear learning intentions and success criteria, while ensuring the use of differentiated activities to promote inclusion and implementing effective classroom management strategies.

2. Research

(CLPL, CPD, leadership)

Teachers participate in continuous professional learning (CPL) and continuous professional development (CPD) opportunities to enhance their teaching skills. They also take on leadership roles within the school, such as mentorship or leading workshops, to share their knowledge and expertise with colleagues.

3. Impact

(Attainment and achievement; experiences and outcomes)

The programme emphasises the assessment of student attainment and achievement. Teachers regularly evaluate student progress not just in terms of grades, but also in terms of their overall learning experience. This includes assessing the impact of teaching strategies on students’ engagement, understanding and enjoyment of the learning being provided.

4. Validate

(Learning walks, pupil evaluations, lesson observation feedback)

School leaders and administrators conduct learning walks in which they observe classrooms to gain insights into teaching practices. Pupil evaluations involve obtaining feedback from students about their learning experiences. Additionally, lesson observation feedback is used to provide constructive comments and suggestions for improvement.

5. Evaluate

(Sharing good practice, willingness to change, commitment to improvement)

Teachers and faculties regularly come together to share best practice and successes. This collaborative approach fosters a willingness to change and adapt teaching methods to better serve students. Data from evaluations, including lesson observations and pupil feedback, are used to guide decisions and promote continuous improvement.

Stay focused

The overarching goal of the DRIVE Programme is to ensure all learners receive a high quality educational experience. To achieve this, the programme seeks to address various aspects of learning and teaching, including the development of clear and focused learning intentions to guide instructional objectives.

This then leads to the establishing of challenging, inclusive success criteria to measure student progress, alongside the implementation of engaging and relevant lesson starters to help capture student interest. Over time, the use of differentiated learning activities will come to accommodate diverse learning styles, while teachers ensure that lessons maintain an appropriate pace and level of challenge.

At the same time, there will be acknowledgement of students with additional support needs and appropriate support for them put in place, as well as promotion of positive behaviour management strategies to create environments that are conducive to learning. Alongside this will be the adoption of consistent entrance and exit routines for a more structured learning environment, and the provision of appropriate extension work and homework assignments.

At its core, the DRIVE Learning and Teaching Programme is a comprehensive framework designed to foster continuous improvement in learning and teaching, empower staff to collaborate and innovate, and ultimately provide students with a more meaningful and effective educational experience.

All too often, schools can overcomplicate their priorities and development plans. If, however, we can challenge ourselves to remain focused on our core business – learning and teaching – our schools will collectively advance ever closer to the ultimate purpose of delivering engaging and meaningful experiences and positive outcomes for students every lesson, every time.

Rules of the road

As part of the DRIVE programme, teaching staff will be expected to:

- Keep up to date with workshop evaluations and adjust their teaching methods accordingly

- Maintain ongoing professional learning logs to reflect on their development and growth

- Use ‘commitment cards’ as a tool to demonstrate their commitment to their own professional development

- Update their professional learning and development records to inform annual review meetings and set future goals

Faculties will meanwhile be encouraged to:

- Promote the use of DRIVE workshop strategies within their teams to ensure consistency and alignment in teaching practices

- Support and challenge each other to continually enhance teaching and learning practices

- Complete faculty DRIVE evaluation sheets to assess their progress and identify areas for improvement

- Consider pupil evaluations and regularly consult data to evaluate the impact of the teaching and learning strategies within their faculty

Ed Carlin is a deputy headteacher at a Scottish secondary school, having worked in education for 15 years and held teaching roles at schools in Northern Ireland and England.

Why schools get CPD for teachers wrong

As teachers, shouldn’t the process of teaching ourselves better practice come naturally? Alas, that’s not always the case, observes Adam Riches…

We’ve all sat for hours through CPD sessions, but it’s not always hugely clear how much is gained. Balancing the need for professional development and relevancy to staff is a difficult task. Often, the best CPD for teachers is that provided in the right way at the right time – but it’s not always as simple as that.

It’s hardly a secret that CPD for teachers isn’t always done well (nor that the person delivering it isn’t necessarily responsible for that). So what does make for a good CPD session?

1. Relevance

Getting CPD right for everyone in the room is an almost impossible task. Making aspects of the session relevant to all, however, is not. Effective planning and careful considerations should ensure that speakers and leaders alike spend their CPD time wisely.

The most relevant CPD for teachers and support staff will be that which is clear, simple to implement and – most importantly – likely to leave an effect on the learning at your school that can be sustained. Ensuring a tentative balance between research-informed content and context-specific application will make for sessions that are valuable to teachers.

If the content is too research-focused, you run the risk of alienating your context. By the same token, if you focus too much on ‘How we do it here’, you risk of creating a silo effect where staff focus on the how and not the why.

CPD for teachers that promises to help reduce workload is, of course, universally relevant. With the workload issue now firmly on the radars of most leadership teams, it’s worth ensuring that any dedicated CPD time presents teachers with opportunities to develop ways of managing their existing stress and workload, as opposed to merely adding extra things on to an already stuffed ‘to do’ list.

The days of CPD for teachers amounting to whatever information SLT needed to dump on staff and expecting instant results should be a thing of the past. Good CPD sessions are reactive to need, useful for teachers and form a part of the wider school vision.

2. Time

Schools are high pressure environments in which every minute of time is precious. With that in mind, if we want our CPD to be truly effective, we need to think about when the training takes place, and for how long.

Front-loading CPD in PD Days isn’t enough; staff need opportunities to develop their practice all year round. Saying something in a meeting in September, on PD Day, and then expecting to see it done in all classrooms is a non-starter.

You need to plan CPD carefully, and then drip-feed it throughout the year to ensure that staff are able to process, apply, reflect and adjust accordingly.

This process of development is cyclical. Individuals require time in order to effectively implement what you’ve shown them in training sessions.

Morning sessions can be effective in terms of maintaining energy levels and harnessing input. However, a lot of teachers like to prepare in the mornings. Some members of staff may also have family commitments that make it difficult for them to get in early.

Scheduling afternoon sessions that take place after school tends to be the more traditional approach, but that’s where you start to enter the realm of, ‘Are we done yet?. And that’s to say nothing of the battering your colleagues’ energy levels may have taken over the course of the day.

Balance is the key when timing your CPD sessions for maximum effectiveness and efficiency. The sessions themselves ought to be short, sharp and relevant. We’re all hugely economical with our time management when it comes to our classroom teaching. Why should the delivery of our CPD be any different?

3. Speaker(s)

There’s a certain irony in how often current or former education professionals deliver CPD without taking into account any of the research-based theory or advice we know actually makes for good teaching.

Sitting through a session on cognitive load is much more difficult when the speaker pays little heed to the extraneous load of their own information-dense, overwritten slide show presentation!

Effective CPD ought to be based on the same principles that are (or at least should be) in evidence in our classrooms each day. We wouldn’t dream of standing up for two hours and hitting a class with a lecture accompanied by 54 slides, and then expect them to implement what we’ve told them with no modelling or scaffolding. So why would anyone ever think that’s the best way of delivering CPD?

Internal or external?

Then there’s the ongoing debate of whether you should use internal staff or get external speakers in. Having had the privilege of serving in both roles, I can speak from experience when I say that both have their merits and pitfalls. External speakers can reinvigorate staff by presenting new perspectives on familiar ideas. They can propose different approaches to delivery and provide a sense of motivation.

At the same time, however, external speakers will often lack the contextual understanding of school-specific daily routines, styles and methods. Staff may quickly file approaches proven to be hugely effective elsewhere under ‘That won’t work here’. If you’re getting external speakers in, make sure they’ve undertaken the appropriate prep-work of actually getting to know your school first.

Internal speakers, on the other hand, will have an intricate understanding of how the school works. They’ll usually be in a better place to tailor the session content to the school’s context. It can also be advantageous to have existing relationships between speakers and staff who know each other well. This often results in more sustained and honest engagement throughout the session.

This can be a double-edged sword, though. Staff may not value the CPD if they don’t believe in the teacher delivering it. This can be especially true if it’s a member of SLT with a light teaching timetable, and little evidence of them actually implementing the ideas they’re bringing to the table.

If an internal CPD speaker want to be good at what they do, they must be able to exemplify at all times the practice of the ideas and concepts that they’re seeking to deliver.

4. Forward vision

A keen awareness of what your context needs is fundamental to the delivery of effective CPD. You may get this from learning walks, staff reflections or feedback from your heads of department. It doesn’t matter where you get your information from – so long as it’s a true reflection of the climate within the school.

Once you’ve identified those needs, you should marry them up with the school development priorities. That’s when leaders can start thinking about how best to provide their staff CPD, in the most appropriate order and via the most effective structure. Being informed and planning time into timetables for development is important, for both stability and consistency.

That said, leaders must also be adaptable when it comes to their CPD content. There needs to be some degree of flexibility that allows for different responses according to the emerging needs of staff. For that reason, having a firm grasp of your priorities, using that as the bones and then fleshing this out as the year progresses will provide the basis of a good, sustainable CPD plan.

Staff need to see CPD as valuable. Once that mindset is in place, anything’s possible. Showing that you’re prioritising staff by taking CPD seriously can be a huge motivator, and lead to rapid development.

Adam Riches is a teacher, education consultant and writer.