National Storytelling Week 2025 – UK teaching ideas & resources

Find out about National Storytelling Week in February and get ideas for celebrating in your school…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

“Once upon a time, in classrooms near and far, teachers searched for the perfect way to spark their pupils’ imaginations.” To celebrate National Storytelling Week, we’ve gathered a treasure trove of resources to help every child step into the magic of a story…

What is National Storytelling Week?

National Storytelling Week is an annual celebration of the power of sharing stories. It was created by the Society for Storytelling in 2000.

This year, National Literacy Trust has created the theme ‘Reimagine your world’ for its activities and resources, with the aim of helping children craft extraordinary stories from ordinary places.

When is National Storytelling Week?

National Storytelling Week 2025 takes place between 1st-9th February.

National Storytelling Week resources

Official resources

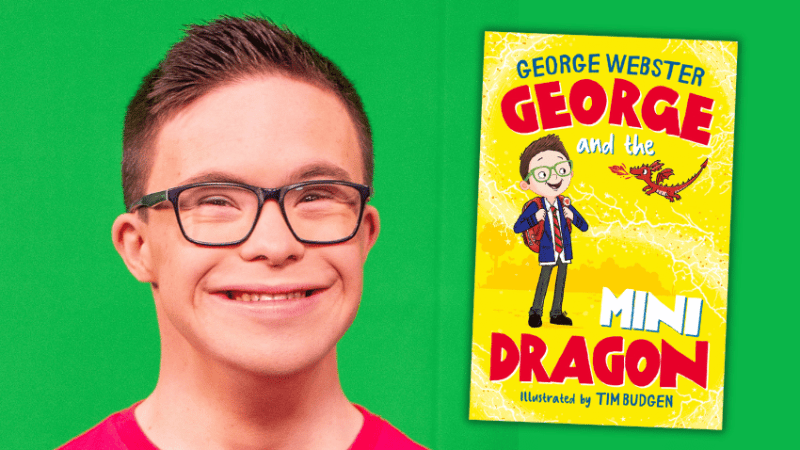

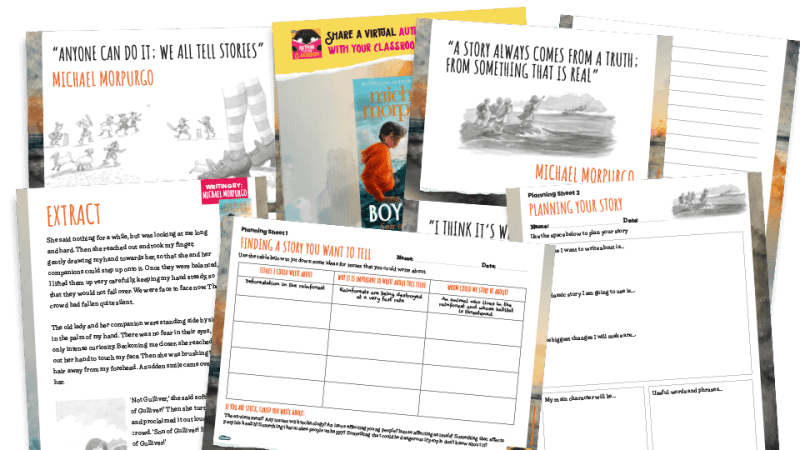

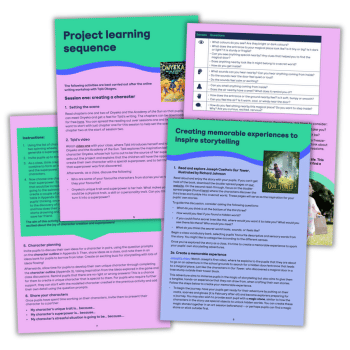

Sign up for a free interactive, online writing workshop with an expert storyteller. There’s Joseph Coelho for KS1, Tọlá Okogwu for KS2 and Steven Camden for KS3.

The workshops are accompanied by short story writing resources to promote a love of writing and storytelling, in a way that also meets national curriculum requirements for writing. Check out the Key Stage 1, Key Stage 2 and Key Stage 3 resources.

At the end of the week, students can submit their writing for the chance to be published in a National Storytelling Week Anthology and receive individual feedback on their work from Amazon.

Storytelling from other perspectives

Storytelling with intertwining versions of the same events can inspire imagination and creative thinking and challenge pupils to think beyond beginning, middle and end.

In this lesson plan, perfect for National Storytelling Week, pupils learn how to develop character and motive and try out new strategies for mapping out stories.

Storytelling cards for oral composition

Use this storytelling cards resource from literacy resources website Plazoom to fire up pupils’ imaginations and support them to orally compose stories based on fairy tales.

The storytelling cards include examples of characters, settings and objects that pupils can use to create new stories.

Story writing lesson plan

Immerse pupils in a spot of imaginary world-building during National Storytelling Week and watch their fiction writing flourish with this free KS2 lesson plan.

It’s designed to immerse your pupils in the art of world-building, generating an instant and unique starting point for their own pieces of writing.

Try Helicopter Stories

In this free PDF, find out how to use Helicopter Stories in your classroom – an exercise whereby children write a short story and proceed to act it out.

Transform your storytelling with ‘three teacher voices’

Use National Storytelling Week to discover the power of telling a story using three different voices: teacher-facilitator, teacher-narrator and teacher-in-role, explains teacher Tim Taylor…

Recently I was working with children new to Reception. They were, as you can imagine, excited about the novelty of being in school and were eager to make new friends and explore the lovely new space they found themselves in.

I knew from experience that keeping them focused on one task, even for a short time, was going to be a challenge, so whatever I did, it had better be interesting.

I asked them to join me on the carpet. Eventually they did. I pulled up one of the classroom chairs. One of the children asked me, “What’s that for?”

I said, “We’re going to start a story in a moment and when I sit on the chair I’m going to be someone in the story. Is that alright?” They shrugged; I took that as a yes and sat on the chair.

Staring in fascination

Immediately I winced and began rubbing my legs. The children looked concerned. I stretched my back and let out a bit of a groan. “Are you OK?” one of them asked. I carried on and began rubbing the joints of my hand and wincing. The children were all now staring in fascination.

I stopped, got off the chair and knelt back on the carpet. “What did you make of that?” I asked. The children started saying I was hurt and unhappy. “Not me,” I said, “I’m fine, it’s the man in the story. What was he doing?”

“Rubbing his legs.” One of the children said. “Yes,” I said, “Why do you think he was doing that?”

“He’s hurt himself!” several shouted out. “Maybe,” I said. “What else did you see?”

This carried on for a bit. The children were now riveted, desperate to find out what was going on. I said, “This time when I sit back on the chair you will hear a bit more, including what the man is thinking.”

Trending

I sat back on the chair and started narrating: “The farm was getting too much for him. He’d lived and worked there all his life, but now his body was starting to ache. ‘Oh,’ he said to himself, ‘there is so much to do. The animals need feeding, the fences need fixing, and now the tractor has broken down! What am I going to do?’”

Once again, I stopped and knelt on the carpet. “What did you hear?” I asked.

Teaching in and out of role

There followed a lively discussion with the children talking about the farmer and the things wrong with the farm.

I said to the children, who had been sitting on the carpet for long enough, “What kind of things do you think there are on the farm?” They suggested cows, sheep, pigs, an old barn and a tractor.

I asked them “Why don’t we draw all the things on the farm? I’ve got some bits of paper here. Draw one thing on a piece of paper and then come and get another. Once we’re ready we can lay them on the carpet.” The children set to work, now busy and focused on a common task.

I don’t have the words to explain what was happening in their heads. It is, I think, extraordinary how even very young children can understand when someone is switching between the real and an imaginary world, representing someone in a story.

I suspect it has something to do with evolution and the way children learnt to make sense of the world around them in the long distant past, interacting with real and imaginary situations through play.

In a Reception class you can see it happening all the time, as well as out in the playground, because it is the primary way children interact and learn.

In the example above I was structuring their innate understanding of play with the use of a strategy called ‘teaching in-and-out of role’, using it to generate interest and to create a context to develop their learning in various ways.

First watching, listening, and using words to describe what they’d seen. Then to make meaning and to contribute to the co-creation of a story, involving a rundown farm in need of repair.

Three storytelling voices

The facilitation of this strategy, which, by the way, is not just for young children, involves using what might be called ‘Three Voices’:

- teacher-facilitator

- teacher-narrator

- teacher-in-role

The teacher-facilitator organises, explains and makes things happen. For example, “When I sit on the chair I’m going to be someone in a story.” And “What did you make of that?”

The teacher-narrator describes events happening inside the story as if they are storytelling: “The farm was getting too much for him. He’d lived and worked there all his life, but now his body was starting to ache.”

The teacher-in-role is a character inside the story: “Oh, there is so much to do. The animals need feeding, the fence needs fixing, and now the tractor has broken down! What am I going to do?”

Generate meaningful activities

By switching between these three ‘voices’ we can make all kinds of exciting things happen in the classroom, create imaginary situations, and use them to generate meaningful activities for learning.

Imagine, for example, the children are back on the carpet looking at the pictures they have created of things on the farm. I carry on:

[Teacher-narrator] “Everywhere he looked the farmer saw jobs that needed doing: feeding the animals, fixing the tractor, mending the roof on the old barn. He knew he needed help.”

[Teacher-facilitator] “Would you like to help?” The children nod, some enthusiastically, some a bit uncertain. “Stand up then.”

[Teacher-in-role] “Oh, you’ve arrived! Thank you so much. There is so much to do! The pigs are getting very hungry, we should start there.”

And so on. Using the ‘three voices’ I can continue to create all kinds of jobs, building a context that develops the children’s knowledge of a farm, as well as generating activities for drawing, labelling, making, talking, listening and working together.

Give it a try – you may just be surprised by how effective a strategy it can be. And how much fun you can have putting it into action.

- Set down an empty chair in front of the class. Explain that the person sitting on the chair is in a story. The class will be able to look at them, talk about them and discuss what’s happening, but the person sitting on the chair won’t be able to hear, see or interact with them.

- Sit on the chair and perform a simple action. Give the class a bit of time to watch, then stand up.

- Ask the class what they saw. Listen to the students’ ideas – pay special attention to what they say about the character’s actions.

- Based on the students’ ideas, use the narrator voice to describe the character’s actions. Speak in the past tense, as if describing someone in a story.

- Tell the students you’re going to sit on the chair again. Ask them to think about what might be happening in the story: who the person might be, where they might be, and what might be happening. Sit on the chair and repeat the action.

- Ask the students for their suggestions, keeping it speculative: “It might be … it could … perhaps ….” Ask them for more details to develop their ideas.

- After two or three ideas have been developed, incorporate the students’ ideas and develop a story. Use the narrator voice.

- Finish your storytelling at a point that feels satisfying – this could be a point of tension, or a question left hanging in the air.

Tim Taylor is a teacher, teacher trainer, and author of A Beginner’s Guide to Mantle of the Expert and Try This… Unlocking learning with Imagination, with Viv Aitken.