Story mountain – Best story structure worksheets and resources for KS1 and KS2 creative writing

Teach primary children this simple five-stop story structure technique to help them write great fiction, with these activities, ideas and other resources…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Introduce your pupils to the story mountain model and equip them with the tools to craft compelling fiction…

What is Story Mountain?

Story Mountain is one story structure or story map that can be taught to children to help them with creative writing.

As the name suggests, these stories build to a big climax or obstacle that needs to be overcome, before being resolved and ending on the other side of the ‘mountain’.

The five parts are:

- Introduction/Beginning/Exposition

This is the introduction to the world of the story and the main character(s) - Build up/Rising action

These are the events that interrupt this everyday world, a rising tension that leads us to… - Problem/Dilemma/Climax

The main obstacle in the story, whether that’s a big baddie or monster, or just a personal problem like shyness or fear - Resolution/Falling action

What happens after the big climax? Did the character(s) overcome it? How have they/their situation changed? - Ending/Resolution

Telling or implying the moral or meaning of the story as it finishes

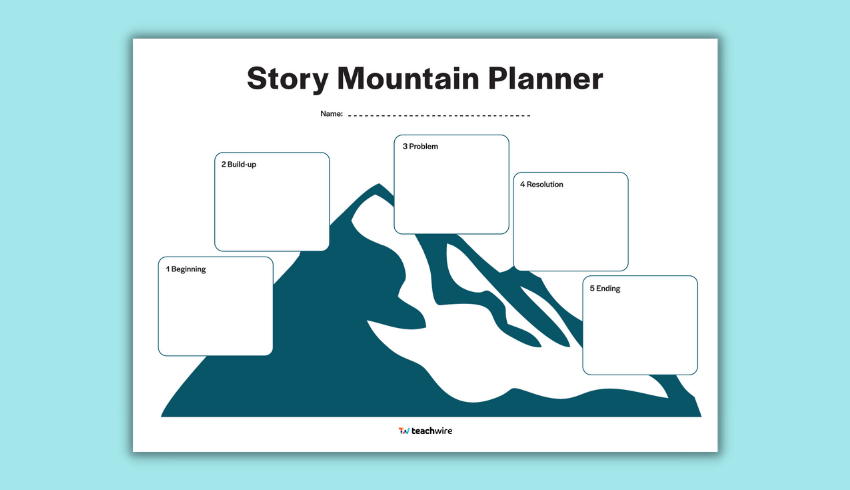

Story mountain template

Want to get straight down to business? Download this free story mountain template.

Story mountain classroom resources

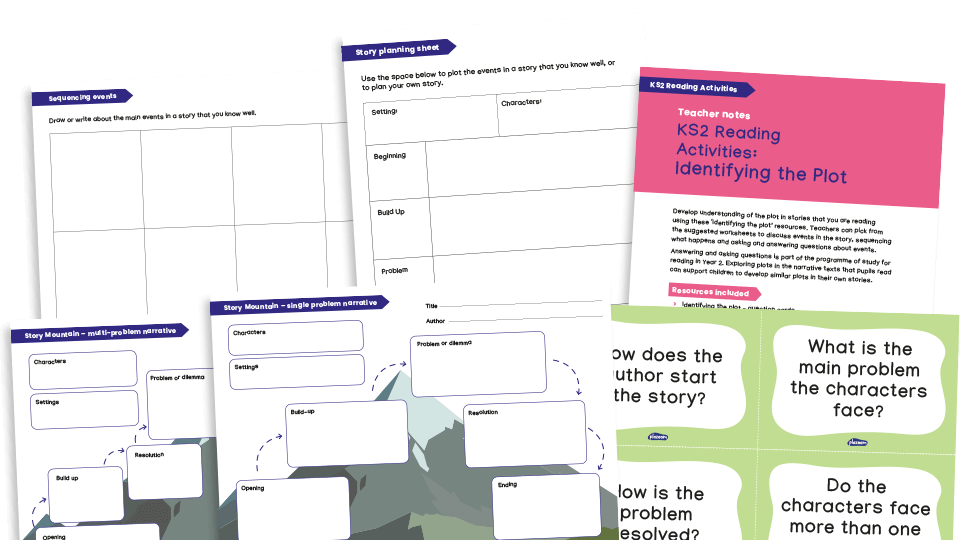

Identifying the plot reading and writing worksheets

Use these plot resources from Plazoom to develop an understanding of the plot in stories you’re reading in school. Pick from the suggested questions to discuss events and sequencing.

In the pack you get question cards, a sequencing worksheet, a story mountain worksheet, a planning sheet and teacher notes.

Find out more about Plazoom.

Plot Diagram Song

Entertain pupils while introducing the concept of story mountains with this Plot Diagram song which will help students increase their storytelling power and learn the elements of plot.

The song is sung to the tune of ‘Big Rock Candy Mountain’.

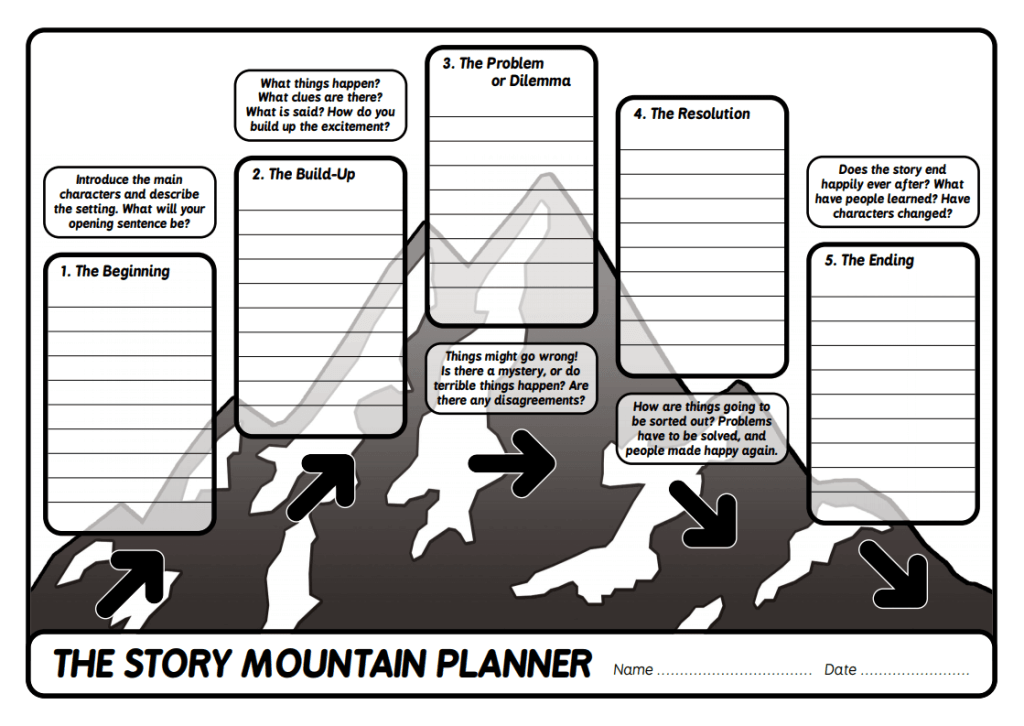

Another story mountain template

This PDF template includes space for children to write key information at each of the five points on Story Mountain. There are also some handy prompts to help them think about what to include.

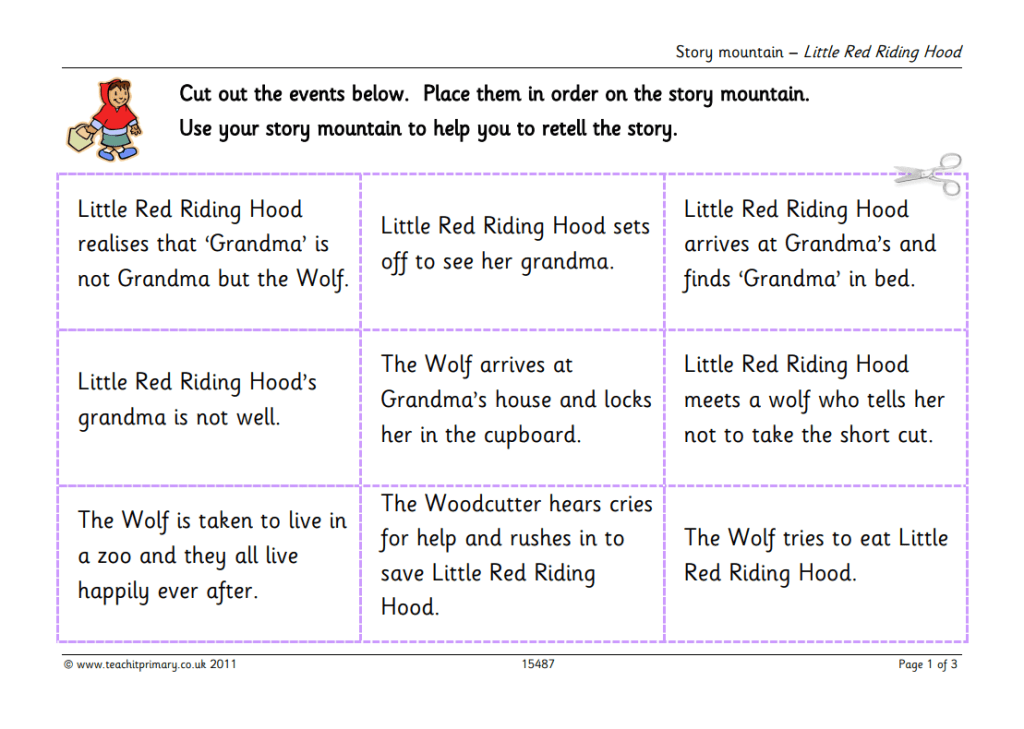

Teach story mountain with Little Red Riding Hood

Introduce the concept of Story Mountain to younger pupils by applying it to a story they should all be familiar with.

This printable KS1 worksheet includes squares to cut out with the key events from Little Red Riding Hood on them. They can then place these on the second sheet – the Story Mountain image. There’s also a third sheet to record key characters, interesting adjectives and time connectives.

You can easily adapt this for other familiar stories too.

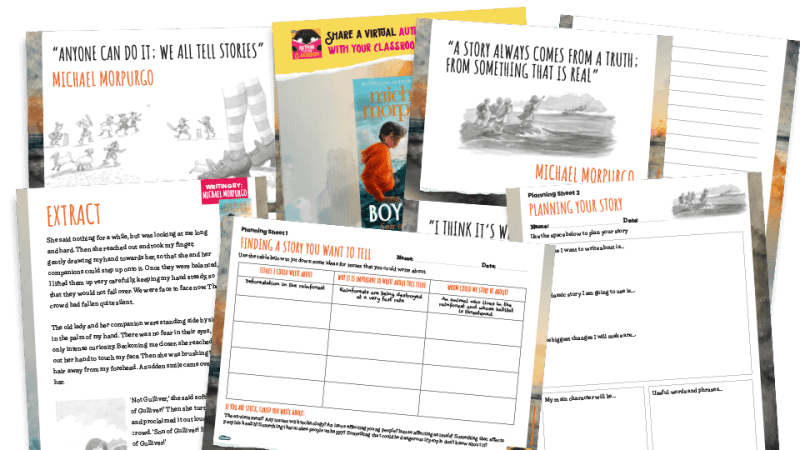

Story writing advice – Author in your Classroom

This brilliant podcast series has been recorded especially for sharing with pupils. Each episode a well-loved children’s author shares writing tips and advice, and there are exclusive resource packs for every episode.

There’s Sam Copeland talking about creating characters, Jamie Littler discussing building fantasy worlds, Struan Murray explaining how to build suspense and more.

A story mountain alternative – circular stories

While Story Mountain exemplifies narratives that rise to a high point before falling back to a conclusion, the language (conflict, climax, resolution, and so on) can be challenging to teach.

Plus, as you’ll no doubt find too, not all of the stories she uses as models for writing necessarily follow this structure.

In Rachel Clarke’s article, she looks into how stories that go round in a circle can teach story structure in a simple and satisfying way.

Alternatives to story mountain

Move away from the standard storytelling model, suggests Stephen Lockyer, and you’ll be amazed at the complex narratives children can produce…

If you were to ask a child in primary school to start a story, most would not have too much difficulty with this.

Story openers tend to be vivid with description, using plenty of adjectives, and painting a fantastic initial picture. Ask them to plot out a more complex tale, however, or even write the ending, and many children become unstuck.

Problems are resolved with incredible speed, storylines are left loose or ignored – and without a gripping or entrancing narrative, the story writing ends up being filled with shallow detail. Why is this, and how can we tackle it in the classroom?

Character is key

Children tend to grow up learning that there are three types of characters: good ones, bad ones and extras (companions or pets). While this works for simple stories, having just three types limits the intrinsic purpose any of the characters in a story actually have.

Unpicking what makes a character good or bad, or the actual purpose of the extras, helps to flesh out the drive of each player in the narrative.

Trending

For example, why is the Big Bad Wolf really bad? If he was just hungry, why did he keep hunting the pigs? Developing his back story helps define him more effectively.

Vladimir Propp wrote about character types many years ago. Thankfully, not only are the types ageless, they can also be taught effectively from a very young age.

The character types are:

- The Hero

- The Helper

- The Villain

- The False Hero

- The Donor

- The Dispatcher

- The Princess

- The Princess’s Father

Now, clearly not all stories have all these characters, but even taking a simple adventure of a boy and his dog getting lost in the woods, uncovering the character of the dog (is she the helper, sniffing the way out of the woods, or is she the donor, uncovering a horde of food?) encourages the presence of the animal to have a purpose.

With older children, the simple companionship of the dog can help drive a story forward.

The story mountain

We have all experienced this: introduction, problem, resolution/climax. There are several difficulties with the story mountain template, not least that it doesn’t distribute the narrative in a particularly balanced way.

No one wants to read a story where a third of it is an introduction to the character. I use the five minutes/25 pages rule as an example in class; a new TV programme has just five minutes to draw me in, or 25 pages of a novel.

In reality, an introduction should take up the first twelfth of a story at most – we are here for the drama, not the setting! On two pages of A4 lined paper, that’s just the first sixth of a page. Get to the problem as quickly as possible.

This is setting out your stall – preparing your reader for a problem that’s about to happen. If you think that a twelfth is too little, consider books or films you have consumed recently.

Jaws starts with a shark attack; James discovers the giant peach in pages; the wolf gets Grandma at the very start of the story. When plotting, begin with the end in mind.

Almost all stories tell of a character who doesn’t change in a new world, or one who is put into a new world and has to change (meaning a shift from normality, although sometimes it does mean a literal new world).

What is the end goal for our character: escape, transformation, saving, winning the prize? When we have solved their primal motivation, the one base instinct they are trying to resolve, we can then build the plot.

Stay the course

Problems are typically singular on the story mountain – it’s at the peak part, and this is where most stories come unstuck.

To help build up the plot more effectively, teach the children to imagine that it is an assault course that is being designed, rather than a mountain – lots of hurdles and challenges of increasing difficulty.

Think back to the Three Little Pigs story – an easy house (straw), then slightly more difficult (sticks), and then insurmountable (bricks).

By working out all the problems, and building them progressively through the plot, you are removing the story mountain, and replacing it with a saw teeth model, with increasing peaks and troughs as you follow the narrative.

Concurrent storylines

Another helpful strategy is to work out concurrent storylines. Developing these helps to flesh out what is happening.

In the ‘boy in the woods’ adventure, write it out in the centre, plotting out above and below what is happening for the boy’s parents at the same time. When do they notice he is missing? What do they do next? When do they alert the police?

By carrying out this task, you’ll find that the children will want to intersperse their tale with alternative scenes.

The biggest benefit of this is that you end up with converging storylines, and a much more interesting, dynamic story.

- Preparation

Use this to come up with a character set and plot, word bank and scenes. Use stimulus materials like story scoring sheets, photographs, props and maps. The aim should be that the children are raring to go, and desperate to write.

- Writing

Using their assorted support materials, set the children off to write. Avoid using the rabbit hole of dictionaries and thesauruses if you can, as they lock up creativity quicker than a wasp in the classroom. If the children get stuck, write a concurrent scene and return to the main plot.

- Refining

Once written, now is the time to polish the final work. Carry this out by reading the work aloud, identifying any errors and correcting them as they go. Ensure that the drama is well-spaced and managed and that the story works well. Emphasise that it should be the aim of every writer to encourage the reader to be desperate to find out what happens next.

Stephen Lockyer is a teacher and author, living and working in South West London.

Browse more creative writing prompts.