Women in STEM – Smashing stereotypes and upping participation in schools

Why are there so few women in STEM, and what, if anything, can teachers do about it? We investigate, with the help of current teachers and STEM experts…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

When talking about women in STEM, education consultant Christina Astin often asks people to close their eyes and picture an engineer. If you do it now, what do you see? A hard hat and hi-vis jacket? Heavy machinery? An older white male?

Hopefully not. But attempt a Google Images search for ‘engineer’ and you’ll quickly see how strong the stereotypes out there still are. It’s a similar story for the terms ‘scientist’, ‘technician’ or ‘mathematician’.

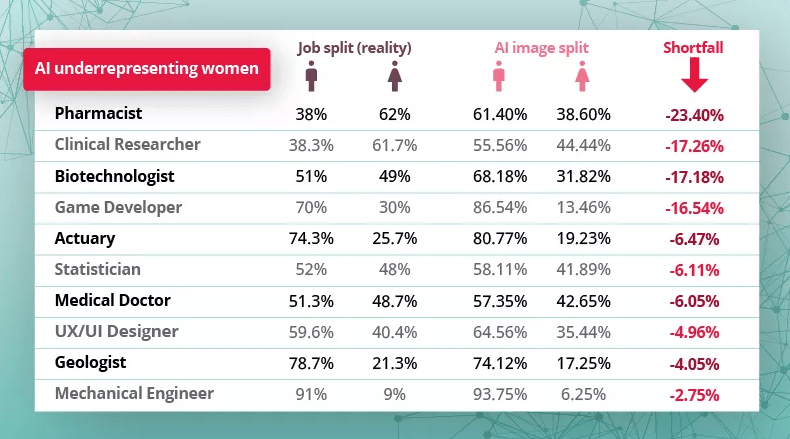

In fact, analysis has revealed that AI image generators are also potentially reinforcing stereotypes by underrepresenting women in STEM.

A report from EngineeringUK reveals that 115,000 more girls need to take maths or physics A Level to balance out the male students studying for engineering and technology degrees.

We know that the proportion of girls choosing A Level STEM subjects has remained stubbornly low for decades. So low that it would take 250 years at current rates to attain gender parity in physics alone.

So why hasn’t this changed? Does it even matter? And what, in any case, can teachers do about it? We investigate, with the help of current teachers and STEM experts…

- STEM resources for teachers

- Where are the missing 115,000 female students?

- How one head of science smashed STEM stereotypes

- How Doncaster University Technical College increased female participation in STEM

- Identifying girls’ potential at a younger age

- Highlighting female role models to encourage girls into STEM

What does women in STEM mean?

“Women in STEM” refers to the presence, participation and advancement of women in fields related to STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics).

How many women are in STEM?

In 2021, only 18% of first-year undergraduates in engineering and technology were female. Women made up just 16.5% of the engineering workforce.

The picture is slightly better for STEM as a whole, with women accounting for 26% of the STEM workforce.

Only 23% of students studying A-level physics are girls, a proportion that hasn’t changed much in 20 years.

STEM resources for teachers

How to encourage girls in STEM

Learn how to start a STEM club for girls, identify girls with STEM potential and encourage girls to participate in STEM and coding with this free CPD pack.

Women in STEM role model resources

Help engage girls in STEM subjects, explore inspirational women in STEM role models and create your own STEM hero with these free resources from QuestFriendz.

More women in STEM resources for teachers

- People Like Us is an online teaching resource that uses film and interactive activities to highlight role models who overcame challenges at home or school before ultimately finding fulfilling jobs in STEM industries.

- The Infinity Game is a quiz-based resource that can raise awareness among students of physics-related careers they might not have previously considered.

- The Institute of Physics has partnered with UCL, Kings College London and the University Council of Modern Languages to create the Gender Action award programme and resource library

- STEMgirls club provides an opportunity for girls to explore STEM careers through weekly, engaging and fun STEM club challenges

- Share videos on platforms such as ClickView about female STEM role models to humanise their stories

- Forces of Nature: The Women Who Changed Science is an ideal resource for KS3 and KS4 science and STEM students. The Matilda Effect, a novel about a girl who loves science but experiences sexism, is great for KS2.

Where are the missing 115,000 female students?

We’re still seeing too many capable girls turning away from promising STEM careers, warns Christina Astin…

Unfortunately, society still peddles the view that ‘science isn’t for girls’. From toy shops to boardrooms, ‘assertive boy / caring girl’ attitudes are continually reinforced by parents and the media.

This makes it tough for teachers to tackle the stereotypes. The idea that girls simply don’t like physics or ‘hard maths’ perpetuates widespread unconscious bias. The result? Girls feel less free when choosing their A levels.

“The idea that girls simply don’t like physics or ‘hard maths’ perpetuates widespread unconscious bias”

I spoke recently to one GCSE student about participating in science lessons, to which she responded with astonishment. “I’d never put up my hand – it’s unfeminine”, she said.

Is it any wonder that teenage girls are so reluctant to pursue subjects with such a stubborn image problem?

Teenage girls are being put off pursuing careers that will lead to them becoming happy and fulfilled. Yet at the same time, diversity is increasingly good for business.

Companies are keen to employ more women in STEM because they know that a diverse workforce makes them more successful.

Women and other underrepresented groups can bring different perspectives to bear on how a company operates. They can strengthen decision-making at all levels of an organisation.

“Women and other underrepresented groups can bring different perspectives to bear”

For evidence of this, witness the flawed designs of numerous products and functions, from airbags to voice recognition software. Their shortcomings for non-male users have only been belatedly recognised and addressed within recent years.

Moreover, given the enormous challenges we face as a society, we can’t afford to discourage any one group from contributing possible solutions. We urgently need more wind turbine engineers, epidemiologists, meteorologists and others who ‘get’ science.

STEM careers

There is some recent research that should give us hope for the future. We understand far better now what will help to fix the leaky STEM pipeline. And teachers have an important role to play.

“Teachers have an important role to play”

Historically, careers advice has tended to focus on becoming ‘a scientist’, and highlighting what it is that scientists ‘do’. This approach has proved off-putting for many who instinctively equate the term ‘scientist’ with the well-worn societal stereotype of a ‘stale, pale and male’ boffin wearing a white lab coat.

Happily, however, prompted by research carried out by ASPIRES and others, we’re now seeing a greater focus on showing school students that there are many people working in STEM who are actually like them. People who look like them, possess similar traits and enjoy similar interests.

There’s also the fact that teachers tend to be the biggest influence on young people’s subject choices after parents and friends.

We can all do more throughout KS3/4 to encourage girls’ interest in becoming women in STEM, beyond the occasional encouraging remark.

Gender-neutral contexts

All students deserve excellent teachers, of course, but research shows that girls depend even more than boys on teaching quality. Their A Level choices often reflect the confidence they have in their subject teachers.

Attracting and retaining STEM teachers who can have a positive impact in this area is therefore crucial. But, needless to say, that’s harder than ever.

Ofsted’s 2023 science subject report highlights the ways in which students learn best. You can also download a useful tips sheet for more inclusive science teaching from Institute of Physics.

You should also ensure that your schemes of work refer to female scientists and engineers. Draw on examples from a wide variety of gender-neutral contexts.

Be careful, though – tokenistic ‘girl-friendly’ references (e.g., ‘The science of lipstick!’) will be seen as patronising.

Having your science, maths, technology and computer science departments work together as a unified ‘STEM’ team can certainly help in this area. You can potentially save time if teaching orders and methodologies are triangulated.

Unhelpful messages about women in STEM

Many schools set higher entry criteria for post-16 STEM subjects compared to others. This perpetuates the myth that you have to be especially clever to study them.

Once again, this invokes those nerdy stereotypes and potentially puts off girls who don’t identify with them.

Having opportunities to meet inspiring STEM role models, in person or virtually, can be invaluable. Cast your net as widely as possible by seeing whether you can invite any parents, governors, local university staff or alumni working in a STEM role to address or mentor your students.

I was told countless times at parents’ evenings, ‘You don’t look like a physics teacher’ or ‘Of course, I was never any good at science – ha ha!’

Neither are helpful messages for daughters to hear. Though it may well be that parents themselves need further information about the possible pathways into STEM – from technical apprenticeships, to graduate careers.

They may also need friendly guidance on what they can do to help counteract negative stereotypes.

STEM learning

Schools that are serious about addressing diversity will make gender equality a priority for the whole school. This might involve making it a standing item on every SLT agenda. Or you might appoint a school gender champion to challenge mindsets and monitor school policies.

Each department could in turn critically examine its curriculum, outcomes and language. This is something that’s just as important for boys wanting to choose drama as it is for girls wanting to choose physics.

Don’t be daunted by the scale of the problem. Even small changes of emphasis can have a noticeable impact in schools and help girls make freer, more informed choices regarding their futures.

“Don’t be daunted by the scale of the problem”

Who knows – maybe we can help find those missing 115,000 women in STEM after all.

Christina Astin is a former physics teacher, now education consultant supporting partnerships, science and outreach. She also chairs Planet Possibility – a consortium working to improve diversity in physics. Find out more at astinconsulting.com. Browse a selection of great activities for your STEM Club.

How one head of science smashed STEM stereotypes

When I saw how disengaged girls were with STEM at my school, I had to take action, explains Amy Ryman…

Having spent the week in assemblies advertising the new STEM club for KS4, and emphasising all being welcome, the end of the day arrives. I watch with an increasingly heavy heart the rabble of students crashing into the classroom.

“40 students, that’s amazing!” my second in charge exclaims afterwards. But I can’t help but feel concerned that only two of them were girls.

I was pleased at the turnout. However, I was not going to let anyone miss out on this. After a bit of digging it appeared I was teetering on the tip of an iceberg.

“We don’t get a look in”, said one of the girls. “They’re too loud”, complained another, when I asked them why they hadn’t come. “What about a club of your own… just for girls?” I suggested. “Can there be cake?” wondered another student.

So it was set up for the following week. I warned them there wouldn’t be anything ‘girly’ happening – we’d be covering the same content as the other STEM club.

Sixty girls

Baking cakes at midnight the night before the launch, I wondered how many I should make. Feeling somewhat optimistic, I went for 30. I thought we could always take them to the staffroom if no one turned up.

“What about a club of your own… just for girls?”

Walking down the corridor at the end of the following day, a rather frazzled looking NQT came rushing towards me. “There’s a big group of girls outside your classroom, and they won’t move along,” she told me.

“They said they are waiting for you!”. I started to smile. To my absolute amazement, when I arrived at the door there were 30 girls waiting to get in. And that was only Year 9.

By the time we started, 60 girls were crammed into the classroom, sharing the cakes one between two!

‘Weird, in a good way’

During the weeks that followed, the girls kept coming back (even without cake). They told us how it felt at last to have a club they could feel ‘comfortable’ in, with the opportunity to ‘make mistakes and it be OK’, and to ‘bring art and science together, which is weird, but in a good way’.

That term the girls designed and built prototypes of devices to help others. One group came up with a simple distiller which could be used in the developing world, to help clean the water from stagnant pools.

Another group worked on a female-friendly Duke of Edinburgh backpack, and there was also my favourite innovation, washable sanitary products for homeless women.

“They told us how it felt at last to have a club they could feel ‘comfortable’ in”

It was in that classroom the idea of STEMgirls Club was born. STEMgirls Club is aimed at 14 to 16-year-olds and consists of ten sessions per term delivered by a teacher at the school and resourced by STEMgirls Club. Staff are equipped with materials that engage the girls in the vanities of engineering and link to engineering careers.

Activities range from designing prosthetic limbs for landmine victims in Uganda, to designing devices and coding them to alert people with disabilities when, for example, their bath has run enough.

Their own words

Although it is still early days, we’ve already been getting some great feedback. “Ever since I was really young, I’d been brought up in an environment where I was constantly taught and told that women are and always will be inferior to men because they simply just don’t ‘have it in them’. And I believed it,” said one participant.

“But then STEM club became a sort of big thing and I thought ‘hmmm, might as well’. If I’m being honest, I thought that STEMgirls would be really girly and cheesy so I wasn’t that interested but I gave it a go anyway and I was really wrong. We do all sorts of cool things like making prosthetic limbs and now I’m starting learn and embrace lots of new skills I never thought I had in me!”

“After joining STEM club I realised how important me being a female interested in physics and maths could be to the real world,” commented another. “I realised I could be someone who could change the way we live in the world. In the future I want to take physics and maths A Level, because of the club’.

Safe environment

Studies have shown that girls take time, and require a lot of questions to be answered, before embarking on a particular career path. STEMgirls club, running over the year, is designed to nurture and allow time and the positive role models required for young women to explore these questions in a safe and unthreatening environment.

Participating schools are also invited to visit STEM businesses, be visited by female STEM role models and have first-hand links with STEM businesses providing opportunities for work experience, apprenticeships and post-graduate positions.

Of course in the long run these girls will need to learn how to adjust to working in what is likely initially to be a predominantly male environment. However, STEMgirls club has started to address gender stereotyping in the classroom more generally.

The boys in the school see their female peers in a different light now, raising the girls’ profile and throwing up questions about unconscious gender bias in our teaching; which has in turn led to teacher training on how not to reinforce gender stereotyping.

- Set up a girls-only club

- Be mindful of the images you use in your teaching resources – try to include an equal number of female and male examples

- Try not to use gendered language when referring to jobs and careers in STEM

- Actively seek out diverse teachers for your team – and in any case, invite positive female role models to your school

Amy Ryman is head of science at Harris City Academy Crystal Palace. If you would like to know more about STEMgirls club or want to join the movement, visit stemgirlsclub.com.

How Doncaster University Technical College increased female participation in STEM

The GCSE science curriculum currently mentions 20 male scientists and not a single woman, reflecting society’s wider disinterest in female leaders in this area.

This invisibility can make female students feel they’re not welcome, since their achievements likely won’t be recognised, or that this simply isn’t an appropriate career for them to follow.

Schools can help rectify this by shining a light on how the achievements of notable female inventors, physicists, engineers and biologists have shaped the world.

Schools can also consider their internal role models. At Doncaster UTC, for example, both curriculum directors for science and engineering are female.

Career options

Many students don’t appreciate how many doors a STEM qualification can open. Some assume that engineering students are destined to be car mechanics, or that computer science students have to become IT technicians, but this couldn’t be further from the truth.

Trending

In reality, STEM qualifications can lead to a veritable smorgasbord of careers, ranging from research, management and sales roles, to jobs within the medical sector or aeronautics industry.

Once aware of the exciting and multifaceted STEM career options potentially at their fingertips, students will be more inclined to explore them further.

“Many students don’t appreciate how many doors a STEM qualification can open”

Schools can also help change the androcentric narrative. Traditionally, STEM subjects are discussed and taught through an androcentric lens, revolving around traditionally ‘masculine’ topics, such as cars, rockets, construction, finance and explosions.

This fuels outdated stereotypes, and risks making STEM seem uninviting to those many individuals who can’t relate to said topics.

STEM is about so much more. It spans renewable energy creation and development, architectural structures (both new and ancient), interface design, logos and branding.

By rethinking the androcentric narrative, we can encourage many more students to embrace STEM subjects.

Work with parents

Gender stereotypes are powerful and persistent but by working with parents, we can break the mould and ensure that today’s young people can realise their potential in STEM careers, regardless of gender.

With strong familial support, female students are much more likely to flourish in STEM subjects.

Schools can help by sharing curriculum developments with parents via newsletters, highlighting notable female STEM professionals and perhaps passing on messages from those professionals that will help widen students’ understanding of the field they work in.

There’s a need for significant changes in the way STEM is taught in schools, and we’re proud to be leading that change.

Doncaster UTC is currently working with other schools across the Brighter Futures Learning Partnership Trust, sharing our gender-balanced resources and best practice.

I hope the strategies that emerge will help more schools tackle STEM stereotypes on a much wider scale. Schools have a responsibility to give all students the best opportunities possible. For us, that starts with tackling the STEM gender gap in our classrooms.

Garath Rawson is the principal at Doncaster University Technical College; for more information, visit doncasterutc.co.uk or follow @doncaster_utc.

Identifying girls’ potential at a younger age

When I was studying engineering at university I was one of seven women in a class of 120. In the intervening years, as women have entered the professions, business and politics in ever increasing numbers, it would have been reasonable to expect engineering to undergo a similar transformation. But it hasn’t.

The problem doesn’t lie in the number of girls taking STEM subjects at GCSE – as many girls as boys study maths and the sciences, and on average they achieve slightly higher grades.

Yet when it comes to A-levels, significantly fewer girls than boys choose to study maths, further maths and physics in particular.

No one seriously thinks that aptitude is the issue. The problem, we are told, is cultural. Various studies claim that girls lack confidence, or role models post-16, or they think that science is ‘uncool’ and ‘nerdy’ and not sufficiently about people, which also conveniently explains why they find medicine attractive.

Any measures that address this cultural imbalance are worthwhile. But are we looking at the problem in the right way?

“No one seriously thinks that aptitude is the issue”

Would it make more sense to focus less on cultural factors post-16 and more on the way we identify and develop scientific ability pre-16?

Perhaps the best way of tackling a gender deficit at the end of school is to accept how much better we could be at recognising scientific potential in both sexes at an earlier age.

If scientific ability were identified sooner, might more students, and many more girls, opt for a STEM career later in life?

The verbal bias

Our education system is heavily biased towards verbal skills. The curriculum and testing regimes place a premium on the ability to grasp word and number sequences, on oracy and literacy.

It is not very good at identifying and developing spatial learners, who tend to think initially in images before converting them into words.

Differences in spatial ability by gender are insignificant and in any case tell us nothing about individual performance.

There is, however, significant correlation between high spatial skills and scientific and engineering ability, according to Project Talent, a 50-year US study of over 400,000 students.

Children who are both highly gifted in spatial and verbal reasoning abilities tend to do well across the board.

But our analysis of GCSE scores in the UK, suggests that those who have high spatial reasoning but poor verbal reasoning scores markedly underperform*.

What is particularly striking is that the gap in exam performance is not confined to English or the humanities. There is also a significant, if less pronounced, divergence in maths and science.

In 2016’s maths GCSE, for instance, 89% of children with good spatial and verbal abilities achieved an A*-B. Conversely, only 52% of those with high spatial intelligence but poor verbal reasoning skills achieved the same, a 37 percentage-point difference.

In physics GCSE, 86% of children with good spatial and verbal abilities achieved an A*-B compared with 58% of their verbally challenged peers. In chemistry and biology the gaps in performance are similar.

Wasted potential

This represents a huge waste of potential. Almost 4 per cent of students in the UK can be classified as having high spatial but poor verbal reasoning abilities – approximately 400,000 children across primary and secondary schools.

There is no intrinsic reason why these children shouldn’t perform well if their spatial ability is accurately identified and their verbal challenges addressed. There are assessments of cognitive abilities that will help and there are strategies schools can employ.

Teachers should understand the techniques that will support the spatial learner, for instance, such as using models and diagrams, allowing children to move and gesture, and talking through real life scenarios and practical examples.

We also need to accept that not all children will do a task in the same way or that there is only one ‘correct’ approach.

Most teachers mirror our education system – they tend to be verbally biased. But they shouldn’t assume that they way they think, and what they find easy or difficult, will be echoed by children.

An inarticulate, low-achieving child may complete intellectual spatial tasks that teachers find difficult with great ease.

It shouldn’t be luck

It’s also not a bad idea to show children how different types of learning strengths can lead to success in certain subjects and careers.

If students, particularly girls, were constantly reminded that good spatial thinking could lead to a bright future in science and engineering, wouldn’t they be more inclined to persevere with STEM subjects?

I was lucky. I had a decent balance of spatial and verbal reasoning skills and went on to a career in engineering at British Aerospace.

But how many women of my generation weren’t so lucky because poor verbal skills hid their innate talent? More importantly, how many are we continuing to miss today?

The annual shortfall of STEM skills in the UK workforce is, according to the Campaign for Science and Engineering, 40,000.

“How many women of my generation weren’t so lucky because poor verbal skills hid their innate talent?”

If we could unlock spatial learners’ scientific potential at an earlier age and engage their incredible talent, perhaps we would have more success persuading girls to stick with science beyond 16. And if we could do that, imagine how much smaller that figure could be.

*The analysis was based on modelling a pool of more than 20,000 secondary school students who completed the Cognitive Abilities Test CAT4 in Years 7 to 9 and GCSEs in 2016.

Sarah Haythornthwaite was a lecturer in engineering at the University of the West of England. She is now Director at GL Assessment. Download GL Assessment’s report, ‘Hidden talents: the overlooked children whose poor verbal skills mask potential’.

Highlighting female role models to encourage girls into STEM

Computer engineer Barbie may have been an own goal, but we must find ways to encourage girls into STEM, says John Bolton…

There have been redoubled efforts to promote women in STEM in recent years. In 2013, toy manufacturer Mattel chose to tackle the problem head-on, by releasing a computer engineer Barbie.

The doll was inoffensive enough, with geometric glasses, a Bluetooth headset and a binary code form-fitting T-shirt.

Where they went wrong was in the accompanying book, in which Barbie works on designs for a video game, rather than actually coding it (for that, she says, she’ll need a boy’s help). The book was unceremoniously pulled a while later, never to be seen again.

In fairness, the situation is so dire that any attempt at change has got to be a good thing. A 2017 study found girls as young as six were already more likely to associate high-intellectual ability with boys rather than girls.

Other studies have found it is a lack of confidence – not ability – that discourages women from STEM subjects.

The shortage of women in STEM is not, in my experience, due to a lack of interest. I believe it’s down to a scarcity of encouragement and access.

When I was growing up in the 1980s, my understanding of gender identity came down to this: He-Man for boys, She-Ra for girls. Not much has changed. Toy cars are drones, Barbie is an astronaut and skateboards hover, but the same separation remains.

“The shortage of women in STEM is not, in my experience, due to a lack of interest”

High-tech toys

However, happily, we’re seeing an increasing range of high-tech toys that challenge the old gender boundaries.

Recent years have seen a rise in robotic toys that focus on getting children interested in coding at a younger age: the ‘Code-a-Pillar’ is aimed at children as young as three.

Many of these toys are gender-neutral. They take all manner of forms, from interconnected tiles and cubes that children pieces together like fragments of code, to motorised balls like Sphero, which can be programmed along user-defined paths.

A range like SmartGurlz (billed as coding robots for girls) cleverly demonstrates that promoting tech to young girls can be done without compromising on the tech part.

Toys like these are also great springboards to the kind of block-based coding like Scratch that many primary schools already use.

Role models

As well as appropriate resources, young children (not just girls) need positive female role models.

I’ve seen genuine looks of awe in the classroom when talking about mathematician Ada Lovelace, but for children who are too young to appreciate Lovelace’s genius and spirit, we have to capture their imaginations elsewhere. And it seems Barbie did teach us something, after all.

Consider the book Hello Ruby, brainchild of programmer-turned-children’s author, Linda Liukas. Ruby’s superpower is that she can ‘imagine impossible things’, and her favourite word is ‘why?’.

The book introduces programming concepts without the need for a computer, in a way that’s accessible for even very young children.

Even more recently, we got Little Miss Inventor. In the Mr Men/Little Miss universe, role models for young girls are about as frequently salubrious (Little Misses Brilliant and Brainy) as they are dubious (Little Misses Bossy and Princess).

Little Miss Inventor, however, is a paradigm of resourcefulness and creativity, using her intellect to improve her own life and to help those around her. That, after all, is what STEM is about: coming together and improving the human experience.

After-school club

We too must be role models, and strive to change the way girls view their own abilities. They need the self-efficacy to succeed, so make sure women in STEM are visible. Show them what their forebears have accomplished.

For example, if you’re doing a project on space, make sure you talk about computer scientist Margaret Hamilton just as much as you talk about Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin.

Without her, the moon landing may never have happened. Also consider setting up an after-school or lunchtime STEM club. Code Club, a nationwide scheme, is a useful model with plenty of free resources.

And get the boys involved too. You might be surprised by the extent to which they’re on the same side. For me, Barbie’s brief foray into computer engineering wasn’t wasted.

When discussing women like Ada Lovelace and computer scientist Grace Hopper in the classroom, I’ve found describing Barbie’s book to be equally effective: particularly when I get to the bit about her needing a boy’s help to make her designs into a real game. The loudest gasps always come from the boys!

John Bolton is an education writer with a passion for promoting online safety and increasing girls’ participation in computer science. Follow him on Twitter at @boltonwriter.