School rules – How to get buy-in from pupils

A group of teachers talk about school rules, how they have (or have not) implemented them, and how to get that all-important student buy-in…

- by Teachwire

Take a look at some fresh approaches to school rules that can help you to transform your classroom dynamics…

Getting school rules buy-in from students

Help pupils understand the why behind school rules with this advice from author, teacher and trainer Sue Cowley…

Why do schools have rules?

We need children to follow school rules so that they can learn in a calm, safe environment, and so that we can teach them effectively.

If children are talking when you are speaking, how can they hear what is being said? If children are out of their seats running around the room, how can they focus on learning?

But helping children learn to behave properly is also a vital life skill. We want our children to behave well in their wider lives, as well as in school. And for this to happen, we need more than systems to control behaviour.

We must help children understand the why behind school rules and help them develop the empathy that’s at the heart of ‘good behaviour’.

Rewards and sanctions

Many schools have a system of rewards and sanctions as part of their behaviour policy. This can be useful for controlling the majority of issues, but it can run into problems when it comes to exploring motivation.

“We must help children understand the why behind school rules”

Think about the messages we send children when we ask that they work and behave well, in return for an extrinsic reward. Similarly, think about the messages we send when we insist they don’t misbehave, for fear of receiving a consequence.

Are we suggesting, even if subconsciously, that the only reason for good behaviour is to receive a treat? Is the main reason for not misbehaving to avoid a sanction, or is there more to it than this?

Resolving poor behaviour

As soon as we step away from a straightforward ‘training’ approach to behaviour, the questions become far more complex. It’s fairly straightforward to apply rewards and consequences, in the hope of creating a climate for good behaviour.

“Are we suggesting, even if subconsciously, that the only reason for good behaviour is to receive a treat?”

It’s much more difficult to think about the reasons behind poor behaviour, and what we might do to resolve them. We know from the statistics that many children excluded for difficult behaviour have SEND.

Clearly there’s a link between the difficulty these children have in accessing learning, and the behaviour that we experience. Those children from chaotic home backgrounds often lack the role models they need.

If a child hears his parents swearing, or sees them becoming confrontational in the face of difficulty, this is the model they may bring into school. Teachers becomes an important example of what ‘good behaviour’ looks like.

The more explicit we make the model we offer, the better placed our children will be to replicate it.

- Talk about the why behind your school rules. When you need children to listen or work silently, give a reason. If you insist a child returns to their seat, outline why it’s necessary for learning in this situation.

- Chat about the emotions other children feel when a peer behaves badly towards them. Why might some behaviour upset or anger others? Read stories to develop pupils’ empathy, particularly ones that explore how a character’s behaviour impacts on others.

- Talk about the moral code you are trying to create as a community of learners. Why is it important for children and adults to behave in this way? What does it mean for the learning that happens and the way we feel in school?

- Explain your own emotions around behaviour. Show children how you’re able to control your instinctive responses to stressful situations. Help them learn to do this too. If you make a mistake, be explicit about it and talk about how you solved it. Don’t be afraid to apologise if your behaviour doesn’t live up to the model you want to present.

- Talk about how learning is closely linked to behaviour. Stress the importance of focus, concentration and effort. Show how learning links to the wider world, and the kind of long-term benefits it offers. Show children that the main ‘why’ behind good behaviour is a positive not a negative – it is the pleasure and joy that learning brings.

Class rules worksheet pack

Use the activities in this KS2 class rules pack from Plazoom at the start of a new academic year to discuss rules in the classroom and develop pupils’ oracy skills. There’s also a similar classroom rules pack for Key Stage 1.

Embedding new school rules in five steps

- Cover your classroom rules display. Tell students they have 2 minutes in silence to write the rules down exactly as they’re written on the now concealed display. It doesn’t actually matter if they can’t remember the precise wording; what matters is that they’re trying to remember the wording, and thus really thinking about what the rules are.

- Students share their written responses with a partner.

- Ask a student to read what they’ve written for rule 1, then uncover rule 1 on the display. Thanks to steps 1 and 2, our student will be invested in finding out its exact wording. Repeat this approach until all rules are displayed, with students correcting their work along the way.

- Ask the question, “Which of these rules is the one that will help you learn best in this classroom?” Allow students 30 seconds of thinking time, followed by 2 or 3 minutes of writing time. All written answers must include the word ‘because’.

- Students share their pair work; you then select two or three pairs who will read their responses out to the class. Praise any pro-learning or pro-social points, and drill down for deeper thinking if needed. Finish by crisply moving on to the next part of the lesson.

Robin Launder is a behaviour management consultant and speaker; find more tips in his weekly Better Behaviour online course. Visit behaviourbuddy.co.uk

Swapping ‘school rules’ for ‘terms and conditions’

What would happen if all incoming students were invited to sign a contract clearly outlining certain T&Cs, asks deputy headteacher Ed Carlin…

What happens at your school when a student causes persistent disruption? Normally staff seek to correct the student, reprimanding them and outlining the ‘consequences’ that their behaviour will have.

And yet the student knows that the consequences are, at best, pretty unrealistic. The adult knows that the child knows this. Everyone moves forward a with a little less respect for each other and the system as a whole.

Alternative to school rules

To be clear, I’m not suggesting here that we don’t challenge negative behaviour in our schools. Of course we do. We should – we must. But let me present a possible alternative.

Where else in our society are we confronted with this notion of ‘rules’ in such a blunt way? Outside of sports (and possibly board games), young people will rarely enter spaces and be immediately welcomed with the message, ‘In this place, the rules are as follows…’.

It just feels so dated and irrelevant. This is especially true when compared to most of the situations and places that young people will typically experience in their lives outside school.

Yet when they’re in spaces where certain rules very much apply – a leisure centre, say, or a train station – they’ll tend to not behave in the same negative manner which might see from them in schools. Why is that? I believe it’s because they’re intrinsically aware of how to behave, based on the context of the space they happen to be in.

What we must therefore do is aspire to a culture of purpose in our schools. This is one where we regularly share with our students what they’re there for in the first place – namely to:

- learn

- develop skills

- gain qualifications under the guidance and support of trained professionals

Playing it safe

This way, everybody knows what they’re playing for. Issues begin to arise, however, when school leaders become so fixated on specific policy, rules and regulations that young people start failing to see the relevance of them.

Countless times throughout my teaching career I’ve heard young people express frustrations and complaints, and raise what I’ve always felt to be fair questions. ‘Why do we have to wear a uniform but staff don’t?’. ‘Why do teachers shout at us when we do something wrong, but nobody’s allowed to shout at them?’.

I tend to play it safe and answer such questions with the usual excuses – ‘It’s different for staff’ or ‘They’re older and able to make better judgements’.

Although, in my heart of hearts, I know there are times when those reasons don’t apply. In fact, much of the inappropriate behaviour I’ve dealt with as a school leader has often been down to negative behaviour from staff, and the mishandling of situations that ought to have been fairly straightforward to address.

“Much of the inappropriate behaviour I’ve dealt with has often been down to negative behaviour from staff”

I’m now getting to the point where I think we need to challenge – by which I mean really challenge – the rules we impose upon our students, and rethink those so-called ‘consequences’ that we’ll use as justifications for our actions.

Mutual agreements

Young people deserve to have a school experience that reflects the realities they’ll subsequently go on to face over the course of their lives.

Of course, we should continue teaching our students how to be respectful. We should also teach them how to make the most of the learning experiences we’re providing for them.

But isn’t it time we gave up the disproportionate consequences they’ll often face for failing to wear a school tie, or walking the wrong way down a one-way corridor?

If we want students to gain a better understanding why they should be in school, what it can offer them and provide reassurance that what they’re being taught is both relevant worthwhile, then what are we missing? Not rules, but terms and conditions.

‘T&Cs’ are used by manufacturers, publishers, venue operators and countless other organisations to set out what they see as a reasonable agreement between them and their buyers or service users.

Let’s apply that model to a school. Imagine what would happen if all incoming students were invited to sign a contract clearly outlining certain T&Cs, with responsible adults present.

Having entered into an agreement, there would be far less room for confusion, inconsistency and complaints between staff and students when behavioural issues arise.

After all, your teaching and support staff will have all agreed to a set of negotiated, fair and relevant T&Cs when appointed to their roles. Why not require students to do the same?

“There would be far less room for confusion, inconsistency and complaints between staff and students”

Nationwide issue

Right now, it’s becoming impossible to ignore the huge impact that negative student behaviour is having on our teachers. It’s a nationwide issue, and one that appears to be only getting worse.

I can’t tell you how often I’ve been in meetings where a parent or carer has said something to the effect of ‘How do you do it? I couldn’t work in a school – it would drive me mad!’.

At the same time, I can’t help wondering if many of the problems we’re having are the direct result of an unrealistic, dated and intractable system of school rules that must be obeyed. These cause confusion and conflict for everyone involved, right from the onset.

Ed Carlin is a deputy headteacher at a Scottish secondary school. He has worked in education for 15 years.

The class with just two rules

Want your pupils to lead their learning? Then get the heck out the way, says teacher and ex-Navy officer Matthew Lane…

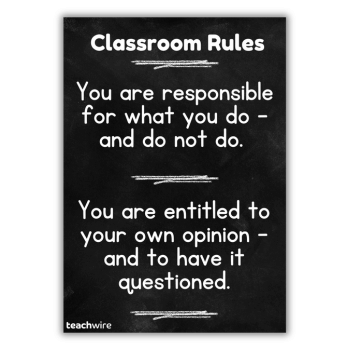

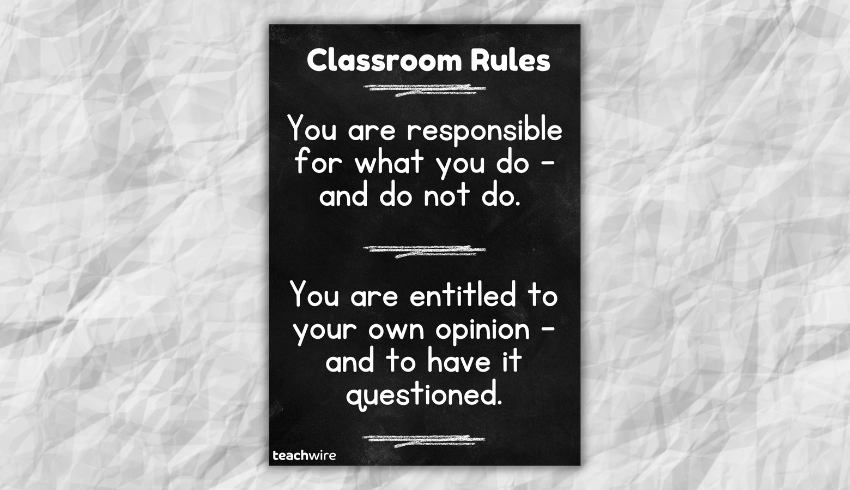

I wanted each child in my classroom to be a leader of their own learning, and a leader within their classroom. To bring this to life, I trialled having just two classroom rules:

- You are responsible for what you do – and do not do.

- You are entitled to your own opinion – and to have it questioned.

Tackling the ‘b’ word

So, what does this look like in the classroom? To begin with, it comes with setting the tone within the first few days of the school year; explaining that we are all leaders and all members of our team.

We discuss leadership, the importance of leading others and holding our team to account. We also discuss how I and the other adults in the room are there to show the way, not to sit behind pushing them forward.

It also means tackling the ‘b’ word: bossy. It is a word I have come to have a near-pathological hatred for. People readily apply it to girls and it devalues the contribution of others. We talk about language and how we talk to others: “Don’t say ‘You’re doing it wrong!’; do say, ‘Have you tried it this way?’”.

We also talk about the expectation that we will all help each other in our learning. I also discuss how we should readily call upon the expertise and experience of others when we need it, regardless of if the person is a boy or girl, friend or not.

If you need help with your learning, you should be ready to ask for it and accept it from whomever is best suited.

Work worth doing

The first rule, about being responsible for yourself, is as much to do with learning as behaviour. As someone smarter than me put it (and I have this on a poster above my desk):

“Far and away the best prize that life has to offer is the chance to work hard at work worth doing.”

Children are accountable for their learning and the learning of those around them. As a class we make time in lessons to celebrate success and – more importantly – discuss what we found challenging. Children in my class have quietly said to me they feel more confident in their learning when they hear one of the ‘smart kids’ saying they found it hard. It builds mutual respect and bonds the class.

Classroom rules poster

It also means you don’t get a blank page at the end of a lesson because a pupil ‘didn’t get it’ and didn’t ask for help. No child can now sit doing nothing if they are stuck. Their peers will ask them why and offer advice. Equally, pupils will challenge others who they asked to help but wouldn’t.

No one gets left behind – the person tries to keep up and the team doesn’t let them stay static.

Being fallible

As the teacher, I hold myself to the same standard. If I feel a lesson was a success, I tell the class why. Equally, if a lesson has gone sideways, I tell the class and explain what we’ll do next time to fix it. Being fallible builds a lasting respect between class and teacher.

I’ve also found that this ethos stamps out low-level disruption and other unacceptable behaviour. If your partner is distracting others or not engaging in the learning, you should be telling them to stop – not putting your hand up and telling a teacher.

If a pupil sees a classmate being unkind to another, I expect them to step in. To paraphrase the oft-misattributed quote: “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good people to do nothing.”

I have taken to not discussing the ‘golden rule’ (do unto others as you would have done unto you) for this reason. While we rightly should expect children to be kind to each other, it doesn’t speak of their responsibility to ensure others are kind to each other as well.

Words have power

Regarding the second rule, about opinions and having them questioned, in this age of social media, fake news and opinion having more credence than fact, the rights and responsibilities of free speech have taken on a new importance.

As a leader, words have power and consequences. Sticks and stones may break your bones, but words will crush the life out of you.

If we’re asking children to support others, their comments and advice need to have integrity. “I thought your writing was very nice” offers no guidance to a partner, nor leads them to what they could do next. If children are going to critique each other’s behaviour, they need to be ready to explain what word or action they disagreed with.

Getting out of the way

If you want children to lead their learning, you need to let them do just that: lead. The best way to do that is get out of the way.

Children need the space and time to find their identity and style as a leader. They need time to learn when to lead and when it is better to follow. Can it go wrong? Of course. Is it worth it for the pay off? Most definitely.

Matthew Lane is a Y6 teacher and religious education lead at Hethersett CEVC Primary in Norfolk. He was formerly a Navy officer. Find him at theteachinglane.co.uk and follow him on Twitter at @mrmjlane.