Leadership in schools – What does it take to be excellent?

How you can develop your own leadership skills and develop junior colleagues’ abilities to one day lead others themselves…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

What does it take to demonstrate excellent leadership in schools? Experienced leaders ponder this question, and offer advice for creating the next generation of SLT…

How to make a leader

Rob Crowther contemplates the professional development, self-reflection and practical steps needed to advance from the classroom into school leadership…

My original reason for seeking out a leadership role was that I could do more for the kids at our school than I was already.

I believed I could achieve better outcomes by providing learning and teaching environments that genuinely supported them, their teachers and the community. That’s remained the case ever since.

For me, everything always comes back to that one kid who’s sat on their chair in front of you. Every decision you make as an educator will have an effect on that child – from how you work with your faculty, to your interactions with parents and the wider school community.

“Everything always comes back to that one kid who’s sat on their chair in front of you”

It all impacts upon them, to one extent or another.

The infallibility fallacy

Earlier in my career, while working at a school in Jakarta, Indonesia, we had a principal who was incredibly humble. He had an easy ability to laugh at himself and never took himself too seriously.

If he ever got something wrong, he’d be quick to acknowledge it. I’d already worked in a number of leadership roles by that point. However, this turned out to be a huge point of learning for me.

Up to then, I’d always felt that you needed to be virtually infallible when holding a leadership role.

What I learned then, and have taken with me ever since, is that the more you show you’re not infallible, the stronger your relationships with people will be.

You can remain open to new ways of thinking, sometimes not be in possession of all the answers, and be liable to occasionally get things wrong.

“The more you show you’re not infallible, the stronger your relationships with people will be”

Navigating the storm

I don’t use Twitter/X all that regularly now. However, at one time, I used it quite frequently and came to see it as a kind of ‘bitesize’ form of personal development.

I’d often print out advice I’d seen via Twitter on my wall, one of which remains there to this day. It’s a note that says, ‘Bring students into your calm – don’t let don’t let them bring you into their storm.’

I’ve since shared that with our faculty and parents. It’s gone on to become something of a mantra for the school. Remain calm, find a way through the storm, give the storm time to blow out, and then take it forward.

“Bring students into your calm – don’t let don’t let them bring you into their storm”

Ongoing professional development remains hugely important for me. A large part of my professional development this past year has involved making connections at various conferences and events.

However, I’m also finding now that newer, less traditional and more targeted professional development opportunities – ones which enable you to rapidly put things into practice – are becoming extremely valuable.

Vision and values

To those interested in making the move into leadership themselves, I’d advise firstly seeking out good development opportunities. Learn from others and find good mentors.

My philosophy has always been that when somebody asks me to do something – ‘Can you just do this?’ – I’ll generally answer ‘yes’. I’ll then figure out the details afterwards, learning what’s required in the process.

Act on every available opportunity to assume more responsibility and to lead. Also, involve yourself in any opportunities to take students on trips. It’s incredibly important that you get to know them.

“Learn from others and find good mentors”

The extent to which you can connect with students will always come through very clearly when assuming new roles, be it at your current school or any others. Because we’re ultimately in the business of educating young people – and you need to know who they are.

Be curious and be resilient. Get to know who you are as an individual. Finally, try to align your goals, vision and values with those schools you actively want to for work for.

When applying for job roles, I won’t cast a wide net. Instead, I’ll identify those schools I believe are aligned with my vision and values, and the rules to which I subscribe.

I’ve stayed at ACS Cobbham since 2016 because I’m closely aligned with the school’s vision and the values we have. It’s a place where I’d want my own children to be educated.

Rob Crowther is Head of School at ACS Cobham.

Your staff’s hidden talents (and how to find them)

Ed Carlin looks at how school leaders can develop their junior colleagues’ abilities to one day lead others themselves…

From the laying of its foundations, to the first building blocks and final structural supports, every outstanding school will foster leadership at all levels.

There are many ways of building leadership potential among school staff. My aim here is to outline those key strategies that will provide the pathways and opportunities your staff and pupils need in order to really flourish.

Trust your teachers

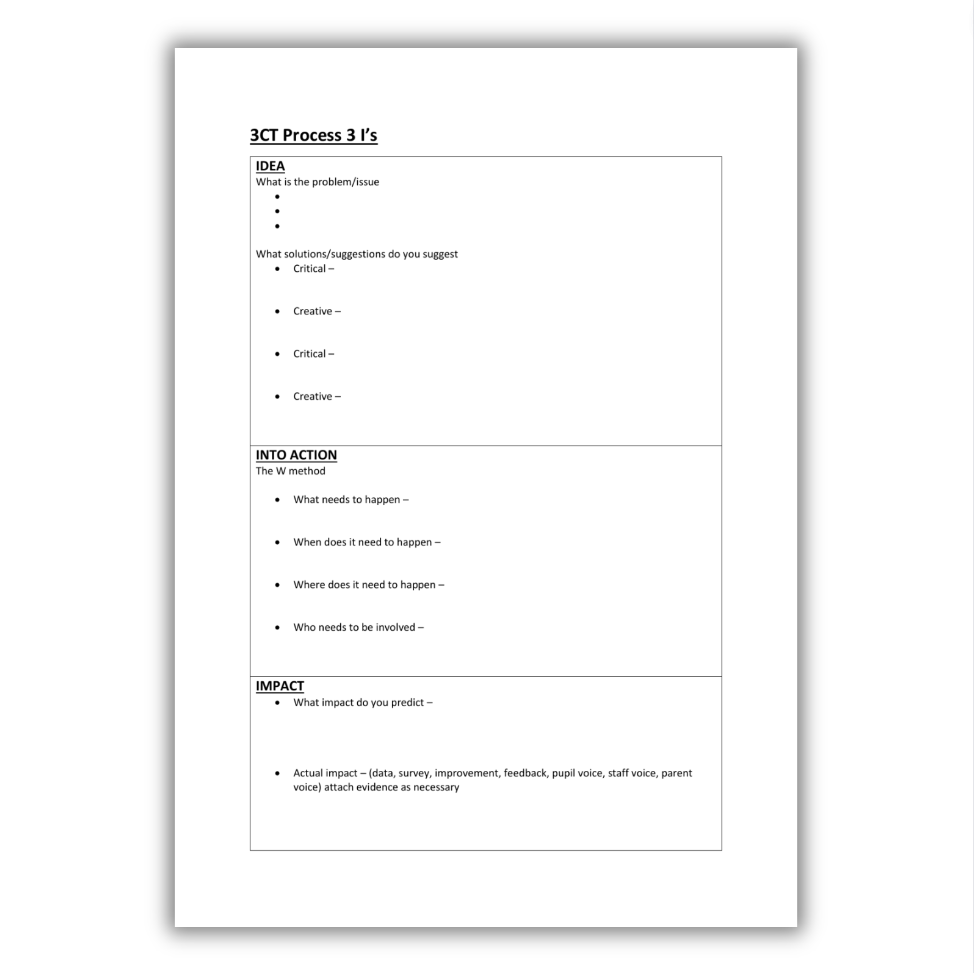

To harness leadership in schools at all levels, we must first develop a sense of intentionality. Make available structured programmes to those wanting to improve their skills and potentially progress to the next level. Provide staff with the right opportunities aligned with the right resources, unprompted, to open the door to more collaborative, critical and creative thinking.

A programme focused on empowering teachers and putting trust in them to take key school priorities forwards – alongside tools for measuring their impact along the way – will provide the confidence and experience needed to lead others, and see school improvements through to their conclusion.

Our schools are peppered with innovative, enterprising and creative staff who possess the ability to bring about transformational change. Too often, however, we confine talented teachers to their classrooms. They’re limited by traditional, yet blinkered approaches to cultivating their leadership skills.

“Our schools are peppered with innovative, enterprising and creative staff”

When it comes to leadership in schools, typically it’s only senior leaders at the helm when it comes to generating ideas for school development and improvement, implementing them and measuring their subsequent impact.

We lose so much talent due to outdated structures entirely reliant on colleagues already in promoted posts leading the school improvement plan.

Yes, teachers are usually given opportunities to make suggestions and potentially join development working groups – but is that enough?

Fertile soil

Imagine instead the shift in mindset we might see when we give an unpromoted teacher a key school priority to lead on and manage.

With the right support and coaching, this could amount to fertile soil in which their true potential will be given the chance to flourish.

Having agreed on the project focus, discuss any barriers that you need to address. This is so you can offset any unnecessary battles along the way. It’s always useful at this stage to follow the ‘W’ method of considering who, what, why, when and where.

Mentors should consider coaching the member of staff prior to meeting. This will help them frame the dialogue. They can focus on what they wish to get out of each conversation with staff they hope to bring on board with their ideas – whatever they may be.

One of the greatest barriers inexperienced leaders can face is having insufficient confidence when holding courageous conversations.

Addressing problem areas and those who might be responsible for them is uncomfortable. But identifying areas for improvement will usually mean that some staff, somewhere, will need to be challenged to accept that change is needed. There can be times when this process is met with resistance.

So what advice should we give to a leader about to shine a light on what’s not working well?

What’s working?

This step is all about timing. Deciding when to meet with a colleague who you need to challenge regarding a particular issue will be pertinent as to whether the project has a successful outcome.

During the meeting itself, you mustn’t direct the conversation in a way that leaves the member of staff feeling chastised or berated.

Focusing in on what’s working well could be a good way of initiating the conversation. But always remember – you’re not exclusively looking to assign fault or apportion blame.

This is merely an opportunity for you to hold a professional and reflective conversation with colleagues about what you, as a school, could be doing better.

The planning process gives rise to the development and predicted impact of the project agreed on by the mentee and mentors.

Having used a forensic approach to planning, by looking inward, outward and forwards a project leader can begin to network and build a team who can contribute to, and implement the action plan.

To lead, support and challenge, this team will be the foundation of all leadership skills developed throughout the course of the project. Which brings us to the essence of this article – commitment over compliance.

Find your goalscorers

I suspect that all of us have experienced the member of staff who signs up for a development group with little to no intention of actually adding any value, or genuinely trying to contribute to the action plan.

This individual may well show up for meetings. They’ll duly nod at appropriate moments to conceal their lack of authentic endeavour.

Yet when the time comes to roll out a specific task, they suddenly become very difficult to track down. This can be to the point where they seem to vanish into thin air – at least for the purposes of my CPD records…

Worse still is when school operates a mandated approach. This is where they expect all staff to be part of one development group or another.

In this instance, our difficult member of staff will likely comply with the demand, but still offer very little in return.

As a project leader, it’s therefore important to quickly identify who will be most effective at securing gains for your team.

After all, it’s better to give the ball to the person who stands a good chance of actually scoring. This is opposed to simply allocating responsibilities based on members’ titles or perceived ‘status’.

Building great teams ultimately means selecting great people – but guess what? Great people are only attracted to great leaders.

In terms of leadership in schools, this means that leaders need to deliver on their vision, purpose and aims if they want to attract people who can in turn deliver on the tasks they’re charged with.

Also, be aware that when someone agrees 100% with a given project’s aims and values, that’s when you get truly unshakable commitment that outperforms compliance every time…

Leadership in schools

In my experience, good leadership in schools is about having the ability to build trust in your followers. Good leaders promote self-belief. They encourage individual team members to contribute to the collective efficacy of the team as a whole.

“Good leaders promote self-belief”

When each member understands the specific role they have to play and feels a healthy sense of accountability, those ambitious plans can quickly turn actions that have visible impact.

By the time a project is in full flow the leader should be fairly hands off, and only called upon when inexperience or unexpected barriers present themselves.

An outstanding leader will have all the mentoring, coaching and collaboration skills to re-empower the team member, identify what the problem might be, and play a part in finding a to the solution.

Great leaders equal great teams – and great teams equal great outcomes.

Ed Carlin is a deputy headteacher at a Scottish secondary school. He has worked in education for 15 years and held teaching roles at schools in Northern Ireland and England.