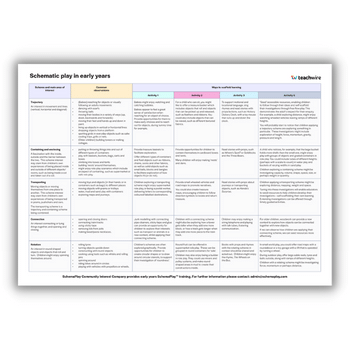

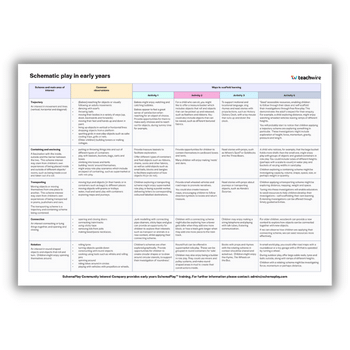

Schematic play in Early Years – What it is and different types explained

When children are absorbed with a high level of involvement, use this to introduce new ideas, consolidate learning and encourage critical thinking, advises Kathy Brodie…

- by Kathy Brodie

- Consultant, trainer, author and founder of Early Years TV Visit website

Read on to discover…

- What schematic play is

- Why schematic play is important for children

- Different types of schematic play

Read in 2-4 minutes…

Schematic play is when children repeatedly practise different ideas or concepts.

There are many forms of both static and dynamic schematic play (see the list at the end of this article for just a few), but by way of an example, a child might be exploring the idea of ‘rotation’ by spinning round outside, drawing circles and spirals, watching the wheels turn on the toy cars or rolling balls.

Initially, these activities may seem to be random, but once you have spotted the fact that they all have a common element – in this case, all are rotational – it is much easier to understand the thinking behind the actions you observe.

Schematic play in early years resource

Learn how to identify common schemes in play, and scaffold children’s learning through activities and play opportunities

Schematic play is characterised by being repeated in many areas of play, from drawings to physical activities, to 3D models and in choice of favourite toy. For early years practitioners, this type of play is very valuable to understand and know about, because it indicates children’s deep-level learning.

When children are exploring their schemas they are usually absorbed, with a high level of involvement. This can be used to introduce new ideas, consolidate learning and encourage critical thinking.

1 | Identifying schemas

Schematic play is play that children are compelled to do. Look out for those activities that really capture their imaginations, where they are fully involved and absorbed. Then really observe it, and try to work out what exactly is it that they find so fascinating.

For example, a boy is mixing paint – is it the swirling round in circles that he likes (rotational), or is he enclosing the whole picture with a box right around the outside of the paper (enclosure)? It could be that he loves painting over the whole picture (enveloping).

2 | Finding evidence

Once you think you have identified schematic play, the next thing to do is to start looking for more evidence of it in other areas of play. Schematic play is most likely to permeate all areas of children’s play, so there may be evidence in a variety of different activities.

For example, in the sand tray, drawings, 3D modelling, and the interests that the children talk about.

3 | Extend their learning

Schematic play usually indicates deep-level learning, because the children have high levels of involvement and are usually strongly motivated to explore their preoccupation. Therefore, providing toys and activities that help children to fully explore their schemas can be highly beneficial.

For example, providing prams, bags, backpacks and diggers, etc. for children who like to ‘transport’ and fabrics, or masking tape and wrapping paper for children who like to ‘envelope’.

Introducing new materials for the children to explore, within their schema, can extend this learning. An example of this might be having small, heavy objects and large, light objects for children to transport.

Trending

4 | Something for everyone

Some toys and activities can inspire a group of children with different schemas. Interlocking train tracks, for example, are good for children with a connection schema (joining things together), a rotation schema (watching the train wheels go around) and a transporting schema (putting things in the train carriages and pushing them around the track).

When you consider the toys and activities that you present from a schematic play perspective, it is much easier to demonstrate how you are supporting children’s individual needs.

5 | Resolving problems

Occasionally some schematic play may be more problematic. If a child is exploring a trajectory schema, this will involve a fascination for items in motion, specifically from one place to another.

This is great when the objects are moving down a ramp, or a football is being kicked outside – but if your child is throwing toys across the room to investigate their trajectory, this may be dangerous.

If that’s the case, you could try to meet the needs of this child by providing safer alternatives, such as using chiffon scarves or going outside and providing a bucket for beanbags to be thrown into.

6 | Work with parents

It can be very useful to share information about schematic play patterns with parents. You can then work together to spot it in action both at home and in your setting.

It may help parents understand their children’s play when it involves transporting, enclosing and enveloping. In addition, encouraging parents to share their own observations, whether this is via a written diary, videos or photos, will help your understanding of the children’s play in a different environment.

7 | Unique children

Not all children will exhibit schematic play. Sometimes children will pass through different schemas in a few days, whilst others may be stuck in a schema for a long time. If you have concerns about your child becoming overly obsessed with an activity or idea, you can start to introduce alternative play patterns.

For example, a rotational schema could be moved on from simple spinning to include up and down motion, using a yo-yo or cars going down a ramp.