Children reading – How we redesigned our approach to school books

Claire Jones reveals how her primary developed a consistent whole-school approach to reading that will prepare pupils for university…

- by Claire Jones

Overhauling the way we taught reading had been on our school development plan for a long time, but other things became a priority and it kept on getting pushed further down the list.

Our end-of-KS2 results have been above the national average for many years and children were reading, so change didn’t seem urgent.

But at the start of 2019, after attending a session at Blackpool Research School on whole-school implementation, I started thinking more about my vision for reading and had discussions with my headteacher around the topic.

As a large school in Blackpool, the most deprived seaside town in the UK, we faced many barriers, but we never put a lid on our children’s abilities to learn.

Around this time, the Literacy Trust conducted some research in Blackpool and identified that in 2019, only 71% of pupils reached the expected level in communication and language at age five, compared with a national average of 82%.

It also found that as many as 32% of underprivileged children in Blackpool left primary school unable to read well.

We knew that the children in our school start significantly below where they should be in terms of speaking, listening and language development.

As a result, it was time to refocus on what our vision for reading was.

It’s all very well saying that reading was on our school development plan, but what was it that we wanted to change? We knew why we had to have it as a focus, but needed a clear whole-school picture.

The Education Endowment Foundation’s ‘Putting evidence to work’ guidance report was a really useful starting point for implementing change.

It breaks the process down into four stages: explore, prepare, deliver, sustain.

Reading for pleasure and reading & writing

At the time I was teaching in Y4 and identified that while we were using texts in literacy, we weren’t giving children opportunities to read a book without having to keep stopping and analysing it.

Teachers read to children but it wasn’t consistent across year groups and books were seldom finished.

In addition, time in literacy lessons was often spent analysing a text with few writing skills being taught. This became increasingly evident when I looked at work in pupils’ books and talked to children about links in the curriculum.

We carried out a staff survey, asking questions about how often teachers read to their class and which text types they chose. We also surveyed pupils and asked then if they enjoyed reading, which types of texts they liked and if they read at home.

We found the Open University’s whole-school development resources really useful during this stage.

Whole-school reading

After spending time in classrooms and holding discussions with teachers, it was clear that we didn’t have a consistent whole-school approach to reading.

A lot of time in Y6 was dedicated to teaching comprehension and preparing for SATs.

Some year groups did reading carousel activities – planning so many differentiated activities took a toll on teachers’ workloads. They would often give groups of children ‘holding’ activities to keep them busy while offering very little challenge.

In addition, different year group teachers were asking different types of reading comprehension questions: some used the ‘VIPERS’ approach (vocabulary, inference, prediction, explanation, retrieval, summarise), while others used different approaches they’d found online.

It was clear we were lacking consistency, clarity, challenge and a clear vision. The surveys we ran made it clear that staff were desperate to improve in these areas.

National curriculum KS1/2 reading

In the national curriculum, the programmes of study for reading at KS1 and 2 consist of two dimensions: word reading and comprehension (both listening and reading).

Skilled word reading involves both the speedy working out of the pronunciation of unfamiliar printed words (decoding) and the speedy recognition of familiar printed words.

Underpinning both is the understanding that the letters on the page represent the sounds in spoken words. This is why phonics needs to be emphasised in the early teaching of reading to beginners (unskilled readers) when they start school.

Good reading comprehension draws on linguistic knowledge (vocabulary and grammar, in particular) and knowledge of the world.

Comprehension skills develop through pupils’ experience of high-quality discussion with teachers, as well as from reading and discussing a range of stories, poems and non-fiction.

Trending

Reading fiction and non-fiction

All pupils must be encouraged to read widely across both fiction and non-fiction to develop their knowledge of themselves and the world in which they live, to establish an appreciation and love of reading, and to gain knowledge across the curriculum.

Reading widely and often increases pupils’ vocabulary because they encounter words they would rarely hear or use in everyday speech. Reading also feeds pupils’ imagination and opens up a treasure-house of wonder and joy for curious young minds.

Redesigning our reading curriculum

I started off by reading the Education Endowment Foundation’s guidance reports on literacy in EYFS, KS1 and KS2. I also found the following three books incredibly useful:

- Reading Reconsidered by Doug Lemov

- Closing the Reading Gap by Alex Quigley

- Hooked on Books by Jane Considine

At the start of lockdown I was fortunate to join one of teacher Ashley Booth’s Zoom sessions on whole-school reading. This was a real ‘lightbulb moment’. Everything Ashley said summed up the findings from our ‘exploring’ stage.

As a result I was able to go away and start redesigning our reading curriculum.

Our vision was to prepare pupils for university and college, where they’ll mostly be reading non-fiction articles.

We worked backwards from there, identifying what we needed to teach our pupils and which skills we needed to equip them with.

This Seuss line proved particularly inspirational:

The more that you read, the more things you will know. The more that you learn, the more places you’ll go.

We decided that reading needed a dedicated, non-negotiable space in the daily timetable.

Distinct reading and literacy lessons

In addition, we decided that reading lessons would be separate to literacy lessons, with word reading and comprehension taught in the former, and writing skills taught in the latter.

Every day, each teacher would read to their class for 15 minutes without any interruptions – just simply modelling ‘how to read’. In KS2, we planned for reading to take place after break between 10.30am and 11.15am, followed by literacy until lunch at 12.15pm.

But what texts would pupils read? We wanted to challenge our children so classic texts were an obvious choice, but when we set about designing a whole-school reading spine that teachers would use to select their class novel, we realised that most of the texts we’d considered were written by white British authors.

We didn’t feel this would prepare our children to be global citizens.

In his book Reading Reconsidered, Doug Lemov says that children should have access to five types of text in order to read with confidence. These are complex beyond a lexical level and demand more from the reader than other types of books.

What school books to teach

To fit our school’s context and our pupils needs, we adapted his suggestions, enabling us to include a more diverse range of text types.

As many staff are avid readers, we were able to identify many books to include, and also used Scott Evans’ The Reader Teacher website for ideas.

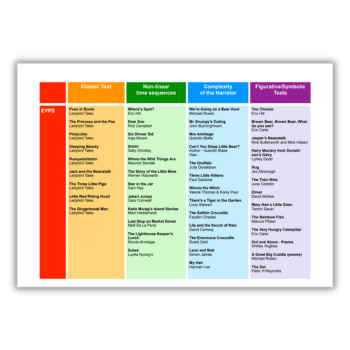

Our reading spine uses four text types:

Classic texts

This involves texts that are over 50 years old and feature vocabulary and syntax that is vastly different and typically more complex than texts written today.

This means you can spend your science lesson practising scientific skills rather than researching. During the reading lesson pupils used their comprehension skills to answer VIPERS questions.

Examples:

Examples include:

Examples include: