Reading for pleasure – How to cultivate a passion for books

Want to instil a genuine love for reading in your students? Here are some practical and inspiring ways to make it happen…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Embarking on a journey to inspire more reading for pleasure in your classroom and beyond? You’re in the right place…

Engaging activities to celebrate reading

Meera Chudasama sets out a series of engaging classroom activities designed to both celebrate reading, and harness the enthusiasms of those for whom the printed word can present a struggle…

Ten minutes of reading

Use blending strategies, whereby audiobooks and other media are combined with the written word. Consider using a broader selection of written forms of reading in your teaching practice.

Students can sometimes find comfort in listening to audiobooks. Try showing them how there’s space for both verbal and written storytelling.

Some of you may already be embedding ten minutes of independent or class reading at the start of your lessons. One way of making this exercise more effective is to immediately follow the reading time itself with some short questions posed to the class. For example…

- Who has read a good introduction to a character?

- Can someone read a favourite part of their book out loud? Tell us why this is your favourite part.

- Has anyone noticed a plot twist, flashback or flash-forward?

Asking specific questions like this, which help to embed knowledge of language and structural features, will soon get students embedding that same language within their thinking.

It should also enable students to start recognising certain literary techniques, and transfer that skill back into the work you set them in class.

You can start to establish links between your own class reader to any books the students might be choosing to read themselves.

If you’re studying foreshadowing, for example, ask students, ‘Have you used foreshadowing in your own story? What impact does it have?’

‘Five seconds’ game

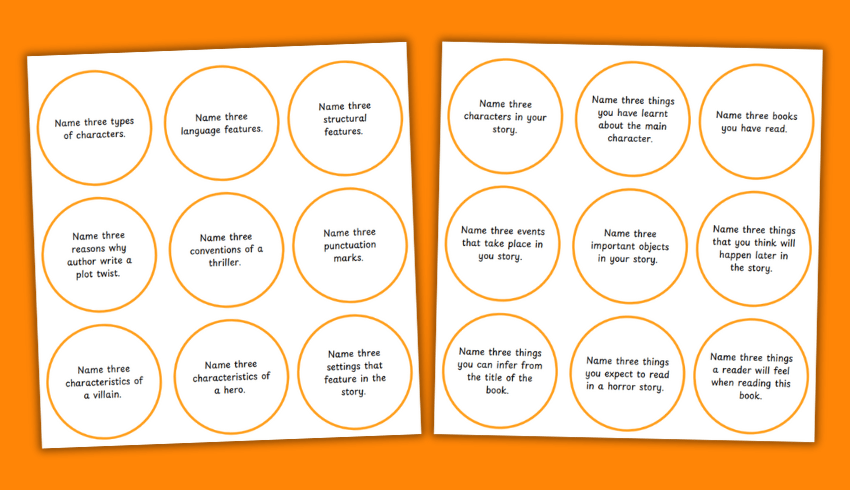

Suitable for pairs or groups, this activity is a great tool for retrieval practice. It can support students in connecting ideas between stories they’re listening to in their own time and those that they’re reading in the classroom.

Follow the steps below and use the accompanying download to organise this game as a starter activity or plenary – it can always be tweaked, amended or even developed further to suit the needs of your class.

Step 1: Download our worksheet featuring ‘Name 3’ prompts. Give each pair/group a pile of ‘Name 3…’ cards.

Step 2: One member of the group picks a card and proceeds to ‘name 3…’ varieties of whatever the card specifies within five seconds. If they run out of time, their partner or another member of the group has a go.

Step 3: Instruct the students to keep a running tally of points, with one point earned per correct suggestion as prompted by the card.

You could introduce an additional incentive by drawing up a class leaderboard.

Tutor reading challenge

This works best with larger groups or as a class activity. The aim of reading during tutor time is to ultimately increase the enjoyment students get from reading – so dedicate one tutor session per week to reading a short story to the group purely for the purposes of pleasure, and not for analysis.

Read the story aloud to model good reading. Be careful to check your intonation and understanding of the punctuation ahead of time. Two good stories to use for this are Lamb to the Slaughter by Roald Dahl and The Red Room by H.G. Wells.

Pause at key moments of the story to ask students questions, such as:

- What happened here?

- What has happened to [X character]?

- What do you think will happen next?

- How could this happen?

- Why could this happen?

Rather than encouraging analysis, though, what we want to do here is encourage students’ interest in the story first and foremost, while developing their understanding of the story’s characters and events.

If time allows, why not add some drama? Once the story’s been read through, have students assume the roles of the story’s characters and continue the narrative orally.

Reading logbooks

With the aid of just a standard exercise book, we can get students to better organise their thoughts with regards to one or more texts that they’re reading.

Design quick activities that task students with considering different aspects of a story they’ve already read. Each entry can work as a separate homework assignment, encouraging students to participate in a range of reading-related tasks. For example:

- Drawing a map or view of a particular location featured in the story

- A short transcription of what a text message exchange between two of the story’s main characters might look like

- Imagining the social media profile of one of the story’s characters and how their posts would read

30-day reading challenge

You can devise a 30-day challenge for your students, or support them in creating one of their own. It involves giving students 30 small reading tasks to complete over the course of 30 days.

Ensuring that these tasks are kept short and easy to manage will give students the confidence to develop their reading skills.

The 30-day reading challenge is a great way of helping students to develop greater breadth and depth in their regular reading habits. What’s more, you could embed half-termly or termly challenges focused on different genres or specific authors.

However you go about using it, this kind of reading challenge can be effective at targeting the needs of individual students.

Text storyboards

This activity can work in many different ways. For students who love listening to audiobooks, or can often be found gripped by a graphic novel, supporting their comprehension of text with visuals can be a good way of blending reading strategies.

You can trial this technique by using a short story and following the three-step ‘read, pause, draw’ strategy outlined below:

- Read a part of the story

- Pause at a point you feel gives students enough stimulus to draw from

- Draw a frame or picture that encapsulates what they have just read

Here, students are utilising their summary skills via visual means. They can support their drawings by writing their own written summaries immediately beneath, or by directly quoting from the text.

Whichever one they opt for, you’ll be able to keep track of how well they’re comprehending the text. For added challenge, make this a timed activity, or direct students’ attention to an area of particular focus – such as the conventions of Gothic horror, for example.

Meera Chudasama is an English, media and film studies teacher with a passion for design and research, and has developed course content for the Chartered College of Teaching.

6 more ways to boost reading for pleasure

Get your whole school excited about reading with these simple steps…

Get to know your children

In autumn term, share a short survey or take time to talk to pupils to find out what their reading journey has been like so far.

Do they enjoy reading? If so, what genres? What are their favourite books and authors? Do they read at home (with and without adults)? How often do they read outside of the classroom?

By getting to know your children as readers, you can adapt any reading corners you have and find enticing books full of recommendations, tailored to their needs and interests.

Get colleagues excited about reading

Do the teachers, teaching assistants and members of the SLT show themselves as readers? At Steyning Primary we start staff meetings with book recommendations and have a WhatsApp group, Book Buzz, to share thoughts and feedback.

I encourage all adults to follow authors on social media and participate in initiatives like the Reading Agency’s Teaching Reading Challenge.

If you get the adults excited about reading, their enthusiasm filters down to the children.

Think dedicated reading assemblies

We hold dedicated reading assemblies where we share different books and highlight different authors, often linking to key awareness days, such as Anti-Bullying Week, or cover books that reflect our children’s experiences, such as being young carers.

Our children take an active role too. We have ‘Books that made me a reader’ segments where pupils interview a member of staff to find out which books got them excited about reading when they were a child.

And, at the end of the academic year, our Year 6 pupils run the reading assembly, sharing their favourite books from their time at the school.

These assemblies are a fantastic way to create excitement around reading.

Ensure access to books everywhere

Books don’t just have to live in a library or book corner, they can be anywhere – on a table in the corridor, by reception, near the hall or in the playground in a reading shed.

Give your children the opportunity to pick up a book wherever they may be. The more your children are interested in the books you provide, the more they will want to read.

Make this even more engaging by tapping into children’s current interests. For example, every January we offer books related to films they may have watched over Christmas.

In October we celebrate the best poetry books to coincide with National Poetry Day.

Review your funding options

We all know that books can be costly and school budgets are getting smaller. Approach your PTA and see if they can provide funding to purchase new books and look into applying for grants.

Our local bookshop started a scheme where community members could purchase books for the school library.

Consider running a second-hand book sale, selling off unwanted stock to raise funds for new books.

Celebrate reading all year round

Think about events that are taking place nationally. Are there books that support that area or topic, whether it’s fiction, non-fiction or newspaper articles?

Highlight different reading materials at key moments such as Black History Month and World Book Day.

At the same time, promote external and internal reading competitions as they’re a great way to build excitement across the school.

Leia Sands is the librarian at Steyning C of E Primary School and Swiss Gardens Primary School. Steyning Primary recently won the Peter Usborne School Library of the Year Award at the School Library Association Awards.

How a good library can turn students into bibliophiles

School librarian Lucas Maxwell recounts he got students at Glenthorne High School to fall in love with reading…

Here at Glenthorne High School we have a huge mix of over 1,700 students spanning ages 11 to 19. To me, as someone originally from rural Canada, this seems massive.

I previously worked over there in a public library when my British wife and I both opted to relocate to the UK. I started working at the school 10 years ago. They’ve been super supportive ever since – to an extent that I’d say is quite rare. When budgets are tight, the school library will often be one of the first things to be cut, but not here.

Complete freedom

I can still clearly remember how the headteacher introduced me to the rest of the staff when I first started: “This is Lucas Maxwell, our new librarian, and he’s going to make everybody in this school fall in love with reading.”

He and the rest of the school leadership had a very clear idea of what they wanted my role to involve. They were prepared to grant me complete freedom in how I went about fulfilling what they expected of me.

Initially, the library provision occupied just one relatively small room. However, two years after I joined, the school embarked on building a brand new library, which was amazing. My colleague and I were even able to play a part in planning it.

Our library is one of the first things visitors notice when they first enter the school. It’s a large, fully open space with plenty of natural light and bookshelves lining the walls. There are lots of movable shelves and other furniture towards the centre.

That’s because from day one, I wanted the space to be used for other activities in addition to reading and studying. This includes open mic performances, which we put on in partnership with the music department.

These kinds of external activities can be good for bringing in students who might traditionally have never thought to use the school library.

We prefer to think of it as more than a traditional library space. It’s a space our students can feel some ownership over.

Fortnightly library lessons

From my own investigations, I’ve found that the national proportion of students who say they enjoy reading for pleasure outside of school hovers around 3 in 10.

The sample sizes were admittedly smaller, and didn’t include every student in the school. However, from carrying out some anonymised internal surveys of our students’ attitudes towards reading, I’ve found their ‘reading for pleasure’ rate to be much higher, at around 7 or 8 out of 10.

That’s in large part due to the importance the school’s senior leadership attaches to literacy. KS3 groups attend fortnightly library lessons. This effectively deliver me a ready audience to whom I can promote the benefits of reading.

That translates into consistently high rates of borrowing. Boys actually borrow books more often than girls. However, I’d concede that’s mostly due to the huge popularity of our Manga and comic books collection.

Welcoming and engaging

We’ve worked hard to make the library a welcoming and engaging space. There’s plenty of soft seating, plus beanbag chairs in our dedicated Manga area that regularly plays host to small crowds. Somewhat selfishly, I’ve always kept in mind the kind of things that 11-year-old me would have wanted to see and do in my school’s library space – musical performances, a film club, a Dungeons & Dragons club, just lots of stuff.

On a more serious note, my role also includes an element of teaching students research skills, aspects of digital citizenship, how to identify disinformation and similar topics.

Those are all areas I’ve actively volunteered to assist with. This is essentially based on my own fears as to how the future is currently looking in terms of our media and communications landscape.

Kids are often much more savvy than we give them credit for. However, they can still be quite naïve in some other important ways.

Reliving the pressure

The latest Ofsted framework talks about reading for pleasure, and the need to establish cultures of reading within school classrooms. Yet without even knowing the half of it, I’m very conscious of just how difficult the workload is for teachers right now.

Much of the work we do in Glenthorne High School’s library are duties that my colleague and I have created for ourselves. This is a good thing – we want to do this stuff, and our teaching colleagues want us to as well.

If Ofsted and the wider DfE mean what they say about wanting schools to hit literacy targets and observe frameworks, then the best way of ensuring that is to let schools hire individuals like me.

Yes, that will mean putting money aside. However, I see part of my role as helping to relive some of that pressure. We have this beautiful space, freedom to try things out, and the time and space needed to create a sustainable culture of reading – which is what the DfE has said it wants.

Demanding that function from teachers runs the risk of it becoming a ‘tick box’ exercise. This is not because building a culture of reading is something teachers don’t care about. It’s more because they simply lack the time and mental capacity to take on any more.

Creating moments

A key way in which we’ve encouraged students’ interest in wider reading is to arrange in-school author visits.

For over 10 years, I’ve curated a social media presence for the school’s library. This promotes reading for pleasure and we regularly tag authors and publishers. This has built something of an audience in the process. It took a while, but our social media interactions ultimately got me on some publishers’ radars.

We also have a website where students can read reviews of books we have in the library and submit reviews of their own via the school’s VLE.

Just publishing those short, single-paragraph book reviews of books led to publishers getting in touch and offering us review copies of books. That then gave way to approaches along the lines of ‘We have an author who’d like to promote their book, would you like them to visit your school?’

Many of the author visits we have now will stem from me having DMed them on social media with an invitation to visit us. If they say yes, the arrangements then proceed through their official channels.

That said, I’m not sure I’d recommend that others follow this somewhat scattershot and improvised approach, even though it has worked. It helps a lot that I’m now in the position of being able to draw on a large pool of contacts built up over time.

Arranging those author visits, opening up the library space, the lessons that take place here – it’s all about creating moments in which everybody can get involved and become invested. What we’ve tried to do is make reading, and all the activities that surround it, a whole school concern.

Anatomy of an author visit

Promotion

Reiteration

I’ll then pass form tutors a copy of the presentation slide I used in the assembly, along with a short accompanying speech I’ve written that they can then deliver. I’ll always aim to make the process of reminding students as easy as possible, in a way that hopefully no one finds condescending.

Messaging

The week before, I’ll be sure to outline the details of the visit and what the arrangements will be to parents in an email. I’ll bring the event up again during any library lessons in the run-up to the event. The PowerPoint slide will now be displayed on several large presentation screens around the school.

Organisation

When the day itself finally arrives, all teachers and parents will receive a final email reminder from me before I start to assemble the year group in the main hall. Much as we might like to host author visits in the library, there isn’t the space in there to accommodate all the numbers.

Logistics

I’ll carefully time the duration of the event so that the start of that day’s morning break or lunchtime falls directly afterwards. Students will enter the hall and proceed to have a full hour’s audience with the author. Teachers are present at all times to supervise behaviour and maintain calm.

Recap

If we find ourselves with 20 minutes or more spare at the end, I’ll try to gather the Y8s that make up our small podcasting team. I’ll help them interview the author for a future podcast. We’ll then share the podcast around the school afterwards.

Lucas Maxwell is the librarian at Glenthorne High School

More award-winning reading for pleasure ideas

Funnies, feelies, and rivers: how two UK teachers successfully encouraged their pupils to take an interest in books…

What do you know about your current class as readers? Do you know more about their decoding and comprehension skills than their attitudes, preferences, and taste in books? Does this lead to imbalanced provision, with reading instruction pushing reading for pleasure to the side-lines?

We cannot and should not measure children’s pleasure in reading. But we can and must develop our knowledge of their:

- identities as readers

- diverse personal interests

- reading networks (or lack of them)

- home practices

Research reveals that knowledge of individual readers positively impacts on teachers’ classroom practices. It builds reader-to-reader connections between adults and children and helps nurture a love of reading.

Can you list the reading behaviours, attitudes, and networks of the less engaged readers in your KS1/2 class?

Do you have enough strategies and research-informed approaches to find out more?

Let’s explore some examples from the winners of the annual Farshore Reading for Pleasure Teacher Awards. This was in association with the UKLA and the Open University.

The winning teachers got to know their young readers, honoured their interests and enhanced their engagement.

Research via surveys

Georgie Lax from Starcross in Devon, winner of the Experienced Teacher Award 2021, wanted to find out about her Year 1 children’s reading interests.

Through using surveys, observations and discussions, she developed a book corner that better reflected the children’s reading preferences.

Reflecting on the children’s favourite books, Georgie found she could categorise most of these into ‘The Funnies’ or ‘The Feelies’.

‘The Funnies’ were books that provided light relief, laughter and escapism from the unpredictable and often unsettling world of Covid. ‘The Feelies’ were books which could support children’s wellbeing, allowing them to connect and empathise with one another during that time.

In particular, Georgie felt the latter often ‘gave children a voice even when they didn’t have the words themselves’.

This investigation into the children’s favourites not only nudged Georgie to read more herself, and to buy new funnies and feelies, but also led to spontaneous book discussions.

Opportunities to relax

The pupils realised their teacher had read these books too, and was open to chatting about them. The initial survey further revealed that being comfortable when reading mattered to most of the class.

So, Georgie began to give them more opportunities to relax and read in their own preferred ways. Some took their shoes off, others sat on blankets, mats or under tables. Some read with friends, others read alone. Georgie joined in too, occasionally offering hot chocolate and snacks.

Gradually the young learners began to develop increased ownership of their reading time. Georgie noted the care and attention they gave to the new ‘books in common’. She was pleased, much more frequently than before, to hear children asking, “Can I get a book?” when they had finished their work.

She also felt better able to make tailored text recommendations based on children’s personal interests.

In the spring and summer terms, Georgie used the survey again, alongside observations to analyse the children’s changing attitudes to reading. She noted that some pupils expressed increased confidence and were beginning to view themselves as readers.

In responding to individuals’ interests and her class’s views, Georgie made a difference to their engagement.

Reading rivers

Amy Greatrex from Wilford in Trent, winner of the Experienced Teacher Award 2022, specifically wanted to enhance her understanding of a group of Reception children who needed support to develop a positive view of reading.

Amy used a number of strategies to develop a richer understanding of the threads connecting the focus children’s choices.

She observed and recorded their selections when they were exploring books, helped the group complete a reading preferences survey, and invited their parents to create a Reading River with them.

Reading Rivers are visual collages which have been used in research to track teenagers’ reading (Cliff Hodges, 2010) and to help primary pupils reflect on their everyday reading lives (Cremin et al., 2014). Amy developed another version of a Reading River with her own five-year-old.

Gradually, they gathered her daughter’s favourite texts, chatted about each, and photographed the resultant pile spread out like a river on the floor. Amy shared this visual with the focus children’s parents and encouraged them to do likewise.

All reading counts

She emphasised that they should only add texts that their child loved; that all reading counts (noting for instance her daughter’s inclusion of Top Trump cards and the Playmobil catalogue); allowed a long timeframe for completion; and chatted to parents informally about it at pick-up times.

After uploading images onto Tapestry, Amy took time with each child to hear more about their choices. She found that the children were drawn to classic texts, Disney, and superhero books and magazines, and were particularly keen on preschool and toddler books.

Honouring their interest in these texts, Amy altered her read-aloud provision and read from these twice weekly. Additionally, recognising the influence of agency in reading, she offered two choices and invited the children to vote by placing a pebble on their desired book.

Book voting

Book voting triggered considerable talk around preferences and personal interests, and some discreet swapping of pebbles, such was the children’s eagerness for their own choices!

Introducing two tall boxes for the pebbles to sit in, Amy simultaneously created an aura of excitement and mystery about which book would be read that day.

Through finding out about their preferences and explicitly respecting and using these, Amy motivated the children’s engagement and supported their emerging sense of themselves as readers.

In July, her school held a Reading Rivers Day with staff modelling their own rivers on the playground, and each class creating one. These were photographed for their new teacher to build upon.

Learning more about your readers’ likes and dislikes, individually and as a class, and honouring these as Georgie and Amy do, nurtures children’s reading rights.

Their tastes and preferences will change as they encounter different writers and genres, so regularly updating this knowledge is helpful, enabling you to plan, connect and more effectively support young readers’ journeys.

How to get to know your readers

- Observing a few target children is invaluable in capturing a sense of their identities as readers in school. You could watch as they browse and choose texts during reading time, when you read aloud, and when they’re chatting informally with their peers.

- Reading surveys help you to explore pupils’ attitudes, self-confidence and home reading. KS1/2/3 surveys and tools to visualise the results are available.

- 24-hour reads are simple collages of books consumed across 24 hours that reveal children’s real world reading and interests. Do share your own to help highlight diversity.

- ‘Me as a reader’ diagrams can help children reflect on their likes, dislikes and practices, and share them.

- Reading conferences enable you to spend some time with individuals – they are most productive if based on surveys, observations, 24-hour reads, or ‘me as a reader’ diagrams.

Teresa Cremin is a professor of literacy in education at The Open University and a judge of the annual Farshore Reading for Pleasure Awards, run in partnership with the OU and UKLA.

Why I hate the term ‘reading for pleasure’

I want my class to enjoy books, but we need to find a phrase that’s less damaging to the cause, says deputy head Neil Almond…

Reading for pleasure has been a key concept in schools for a very long time. As primary teachers, we all know how important it is for children to read in various areas of their lives.

A National Reading Trust report from 2006 stated the vast wealth of benefits of reading outside of school. These included improved reading attainment and writing ability; better text comprehension and grammar; increased breadth of vocabulary; greater self-confidence as a reader, and many more.

But I really don’t like the term reading for pleasure. Here’s why.

Benefits of reading for pleasure

I think it’s incredibly important to distinguish between being able to read, and wanting to. There are many children (and adults!) who are perfectly capable of reading when they need to, but simply choose not to do so during their own time.

Demonising these decisions risks creating even more problems in developing reading skills, making children feel like they have to be reading at all hours of the day in order to get on in life.

Because of all the benefits it produces, of course we’d all love our pupils to enjoy reading. As teachers, then, we should focus on getting children to be able to read, should the desire arise, rather than trying to force them to genuinely like it before they have the requisite skills.

So how can we implement this in the classroom?

Decoding in reading

One of the most important components of setting pupils up to engage in reading for pleasure is to make the decoding process enjoyable.

It makes sense that children wouldn’t choose to read for pleasure if they found decoding frustrating, and therefore couldn’t move through a book at a reasonable speed.

As teachers, we need to focus on phonics and reading fluency instruction to ensure that our pupils have the skills to read fluently and confidently. This means teaching them to decode words accurately and at speed, so that they can read with ease and enjoyment.

We should be using a range of strategies, such as choral reading and repeated reading, to help children develop their fluency and confidence.

Deep understanding

Another key part of reading for pleasure comes from pupils being able to think deeply about the text, and relate the story to their own experiences.

Whole-class reading activities that facilitate conversations around a book’s themes, motifs, plot, settings and character can pique pupils’ interest in how a story develops.

You can also encourage the children to share their own experiences, and relate them to the themes and ideas represented in the book.

If they’re able to connect with a story, whether that’s through personal similarities with a character; recognising an event or theme that’s occurred in their own lives; or identifying with a particular place or setting, pupils are much more likely to want to engage.

Diverse books

Finally, having a wide range of books to choose from is an essential element in learning to enjoy reading. Let children pick a book themselves, and provide them with the time to apply the deep understanding skills they’ve learned in class.

We also need to make sure we have plenty of diverse books in the classroom. Using eBook libraries such as those offered by Primary Ebooks NOW means that pupils can read (or listen) to a large collection of books and comics at home on any device, and schools do not need to be concerned about whether the book will return, or have to keep buying new copies all the time.

Of course, we need to ensure fair access, but according to Ofcom, nine in 10 children own their own mobile phone by the time they reach the age of 11, so providing access to these libraries and discussing the content that’s there may encourage a few more pupils.

Essentially, the point is that the term ‘reading for pleasure’ can exert too much pressure on young children who genuinely do not enjoy books, whether that’s because they find reading difficult, or they haven’t found the right title for them, yet.

What’s important for us as teachers is to do our jobs and teach our pupils how to read with confidence, so should they decide to pick up a book on their own time, they’ll be fully equipped to enjoy the experience.

Neil Almond is deputy head at a south London school. Follow Neil on Twitter @Mr_AlmondED and see more of his work at nutsaboutteaching.wordpress.com. Browse more reading for pleasure activities.