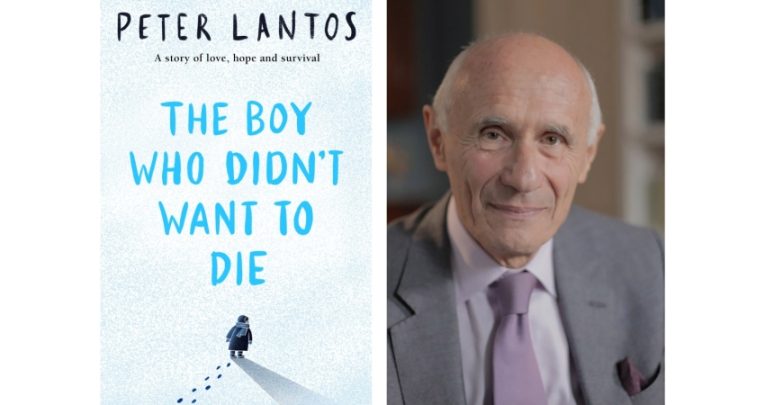

Meet the author – Peter Lantos

A pioneering neuroscientist and Holocaust survivor presents a child’s eye view of one of the darkest episodes in human history

- by Teach Secondary

- Magazine featuring expert advice, inspiring lesson plans and fresh insights

Peter Lantos spent his adult life in the UK, pursuing a highly successful career as a medical researcher specialising in neuroscience, in which he made numerous pioneering contributions to the field of neurodegenerative diseases.

He was also a Holocaust survivor, having been deported with his parents from the Hungarian town of Makó at the age of five and sent to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

Lantos first documented his experiences during this period in a 2006 memoir titled Parallel Lines. His new book, The Boy Who Didn’t Want to Die (Scholastic, £7.99), is a companion piece of sorts, explicitly aimed at younger readers and written from a child’s perspective.

Lantos’ matter-of-fact prose ably captures the puzzlement, imaginative leaps and growing anxieties felt by a young mind when confronted with unimaginable horrors – perhaps seen most acutely in the devastating scenes that recount his father’s death from starvation while the family were interned.

Aside from brief authorial interjections to add historical context, we never leave the headspace of Lantos’ childhood self. For adults, The Boy Who Didn’t Want to Die makes for a poignant read. For its intended audience, it provides an honest, yet accessible and therefore hugely valuable depiction of humanity at its worst.

What was your motivation for writing The Boy Who Didn’t Want to Die?

My generation is the last group of Holocaust survivors. I’m now in my early 80s; I was 5 when we were deported. In a few years’ time, no one will be around to give evidence of what happened. Once we have died, it will just be a fact of history which can be negated.

I felt that telling the story now, for children, leaves an account of what took place. I’ve previously visited schools and colleges to give talks, but with that no longer possible, there will instead be the book.

Was it difficult for you to settle on the book’s narrative voice and sustain it?

It was quite difficult, but once I found the voice, I think it remained reasonably consistent. It’s only when I wanted to point to something – particularly at the beginning and the very end – that I wrote as ‘the writer’ of now, and not ‘the boy’ of then.

I can’t say that writing the book was a happy experience, but it was a satisfactory one. I set out to tell the story as I saw it at the time, as a boy of six. Instead of reflecting on, say, good and evil, I wanted to capture the boy’s sense of surprise and curiosity, and inability to digest the things that he encounters.

How did you personally come to be involved in Holocaust Education?

It started with the publishing of Parallel Lines, which made public an element of my past that even my very close friends of 20 years or more never knew about me. It was around then that I was first approached by schools to give talks, but I was rather reluctant. I don’t like to talk about myself, but I soon realised I had a moral obligation to do so.

Years from now, how would you like to see the history of the Holocaust taught to subsequent generations?

I sometimes feel that the Holocaust is presented as a single isolated event. Instead, it should be embedded in recent history, with students shown how it evolved out of intolerance, discrimination and eventually hate. I’d like to think that people will continue to learn from it – because the more recent examples we’ve seen of other genocides would indicate that those lessons haven’t been learned yet.

For more information, visit peter-lantos.com