Paul Dix – Behaviour advice for teachers, with scripts

Learn how to balance strictness with kindness and discover six ways that you can improve the way you relate to your students…

- by Paul Dix

Hear from children’s behaviour expert Paul Dix about how to balance strictness with kindness and how to be emotionally consistent in your classroom…

Who is Paul Dix?

Paul Dix is a children’s behaviour expert, bestselling author of the When The Adults Change… series and creator of the online Behaviour Change programme for schools. His latest book, When the Parents Change, Everything Changes, is available now. Visit Paul Dix’s website at whentheadultschange.com.

How to balance strictness with kindness

Paul Dix explains how to balance the strictness needed for behavioural rules to be established, with the kindness that ensures students will want to follow them…

Strict teachers in the common imagination are terrifying beasts. Physically imposing, gratuitously loud and generally terrifying. Trunchbull doesn’t do relationships, the Demon Headmaster likes control too much and Professor Snape don’t play.

In real teaching, strict is good. Being nasty with it is not. It’s a fine line for some. You can be strict whilst being kind, and you can be strict while being relational. Just don’t be strict and be a dick with it.

Consistency of response

Nitpicking and overcontrolling through a million unnecessary rules does nobody any good. Micromanaging humans never goes well. Just think about your own autonomy at work.

If you want to be strict and utterly reasonable you need to centre your behaviour work around three simple rules and what we know works – a properly consistent response.

Maintaining a consistency of response from all adults working with children and young people is critical. It’s important enough to put every other strategy into a firm second place, so it makes sense to plan it and agree on it.

Not, mind you, so that all human empathy is sucked from teaching, or so that multiple spreadsheets of responses can be produced by the spreadsheet people.

Plan it so that it is strict and kind, and it will be. Allow everyone to improvise their own responses to poor behaviour, and the variables will kill your consistency stone dead.

Gaps will appear, and those students who like to take advantage of such gaps will be encouraged. It’s the gaps between adults that allows, and can even foster poor behaviour.

Lack of clarity, lack of agreement and lack of consistency are sweet treats for the impulsive ones.

- What you say matters, and what you say in those tricky situations matters most of all. Your tone and physical language also matter, of course – but which words work best?

- • Use ‘I’ve noticed…’ when correcting poor behaviour, or recognising those going over and above. That way, there is no judgement or blame assumed.

- • Try saying the words, ‘I hear what you are saying, and yet…’ to direct conversations back to where they need to be

- • A positive segue from a difficult conversation can be to say, ‘It is important that we remember our rule about Respect – thank you for listening so well, that is how we do it here.

Take-up time

That’s why you need a simple plan for the wobbly moments. All adults with the same consistency. A tight and kind response.

Imagine the impact of that on the behaviour of your class or school, just for the next 30 days. It would be transformational. Behaviour would be as much about the team as the individual, as it should be.

If you can embed a consistency that makes it impossible to put a cigarette paper between the response of one adult and the next, that transformation will last.

None of this needs to be oppressive. You can have a well-structured intervention script for when a child is repeatedly disruptive, a plan in each classroom that’s designed to support (not simply to sanction), and language that seeks to encourage, not condemn.

The speed at which warnings and reminders can be delivered by a frustrated adult is incredible. Poor behaviour tempts us into an unnecessarily urgent emotional response, when what’s really needed is ‘take-up time’ between conversations – time for the irritated, seething and/or embarrassed student to recover, time for you to catch up with those who have been on it from the start, and time for you to breathe.

The minute we need

Standing over a child and demanding that they immediately comply might feel like the right thing to do in the moment, but there are always consequences – and not just for the child.

Take-up time slows escalation, protects pride and minimises disruption. It ensures that students are never cornered.

Often, a reminder or a warning of poor behaviour is just bare. It might be given across a crowded room, or incidentally and not be underlined.

Better instead to deliver it privately, with one minute of your time, because that investment of a minute now could save a great deal of time later.

The minute is a check-in to make sure that they understand the task. That they’re sitting where they can focus. That they can calm their other thoughts. It’s the minute all of us need when we wobble.

Done gently, it’s always seen as fair and kind. It’s a relational minute that the student will remember, even if things don’t go the way you want: ‘I know, you checked in with me too, I’m sorry, but…’

Whatever the outcome, your behaviour starts to have an effect. You’re paying currency into the emotional bank, even when things are difficult. That matters.

Unexpected moments

Even with the best planning, we can be blindsided. You might have given perfect private reminders and warnings, but they didn’t quite land, and now the student decides to escalate.

The third time you intervene will be the last time that the student gets to be in control of what happens. After that point, you’ll decide if they move within the room or need to move out of it.

It might be tempting to deliver the third intervention a little more harshly. Almost as a threat to what might happen: ‘If you don’t stop doing that RIGHT NOW, I will have to have you removed by the gnarled deputy head with the shiny suit and thousand-yard stare…’

Instead of reaching for the panic button, try reminding the student of their previous good behaviour. I know that sounds counter-intuitive, but it works.

Right at the moment when you land the consequence on the child and they start to protest, you lead with, ‘Do you remember earlier/yesterday/last week, when you worked with so much determination? That is who I need to see today.’

From the child’s perspective, this is an unexpected moment. Conversations don’t usually go like this. Just as their urge to protest the consequence is rising, they’re reminded that they’re better than that.

Trending

That they can and will achieve. That they can find calm and focus in your classroom.

Reminding them of previous good behaviour is easy if you practice positive noticing – then you’ll have lots of ready examples of the good stuff.

Three simple rules

‘Strict’ is about making sure that students follow the rules, so it makes sense for those rules to be made as simple as possible.

No more than three, represented by three words, and referred to in every conversation around behaviour, be it to correct or to praise – the same three pegs that everyone returns to.

They shouldn’t be rules that fall from the mouths of adults and are endlessly repeated on roller banners around the site.

They should be rules that make sense, and can be adapted to any and every situation. You don’t need the false consistency of 50 rules; you need the true consistency of three.

There is a deep consistency to the same three words – Ready, Respectful, Safe – being used consistently, every day, by everyone.

Very quickly, these rules become ‘How we do it here’ and the school culture shifts. Before you know it, parents are using the same rules at home, and relational practice starts to make sense in school and beyond the school gates.

If you want to upgrade your school culture, then being strict is important. Being kind is essential.

How to be an emotionally consistent teacher

Paul Dix suggests six ways that you can improve the way you relate to your students and improve behaviour along the way…

Refine routines

Predictability makes classrooms feel safe and routines are central to this. In lessons, refining routines so they can be triggered quickly and executed deftly is a driver of productivity.

Without refined routines, there is too much improvisation and too much chance of some children losing their way, day after day.

However, remember that there’s a world of difference between teaching positive routines using gentle reinforcement that pupils enjoy and drilling children with micromanaged compliance routines. The latter is more about exerting authority than improving teaching and learning.

Be the unprovokable adult

If you wear your heart on your sleeve you undermine the emotional security you should be nurturing. The direct connection between a child’s behaviour and your own emotional state is obvious. The temptation for any child is to see how they can provoke you.

If you lay out a buffet of adult emotions by saying something like, “Jasmin, if you interrupt me one more time I’m going to explode!”, don’t be surprised if some children want to try everything on the table. The connection between your emotions and their poor behaviour is one that you need to break.

“If you wear your heart on your sleeve you undermine the emotional security you should be nurturing”

Instead, make the connection between their behaviour and the standards you expect in your lesson.

Co-regulate

Self-regulating is difficult, complicated and, for some children, an unrealistic expectation. Putting the punishment away and shifting to support mode is a key skill of an emotionally consistent teacher.

This might be as subtle as gently mirroring physical tension during a conversation or as obvious as lying down next to a child who has taken to the floor in distress.

In moments of crisis, threats of punishment are futile. What children need are adults who are not just regulated but who have a flexible, responsive and adaptable plan.

“In moments of crisis, threats of punishment are futile”

Nurture from the first step

Nurture starts at the school gate and the classroom door, whether that’s a simple greeting, a high five, an elbow bump or a salute.

Accept that on some days you won’t feel like it, but for many young people it is the only positive adult greeting they ever get. The quickest way to kill enthusiasm for meet-and-greets is to force adults to greet children in a certain way. No grown-up needs that level of micromanagement.

The point of it is to make children feel safe, not to make adults feel awkward.

The first beats

After an emotionally regulating meet-and-greet come the first beats of your lesson. As the pupils enter the room, identify – often loudly, sometimes subtly – the behaviour you want to see and acknowledge it.

Bury children in positive affirmations and acknowledgements and the climate of the lesson will begin to take shape. The fastest way to get a class of children to settle is to praise the behaviour you want to encourage.

Don’t do ‘rules day’

The ‘rules lesson’ is ubiquitous in many schools. The idea is to lay out the boundaries from the start so that everyone understands how to behave immediately.

Sounds easy, right? However, you can’t establish consistency in a single lesson any more than you can teach pupils how to behave in a single lesson.

“You can’t establish consistency in a single lesson”

Your students need high expectations, tight routines and essential rules drip-fed over time. Delivering it all at once is as realistic as delivering the entire science curriculum in a double lesson. Break down the rules lesson into smaller pieces and scatter them throughout your teaching in the first two or three weeks.

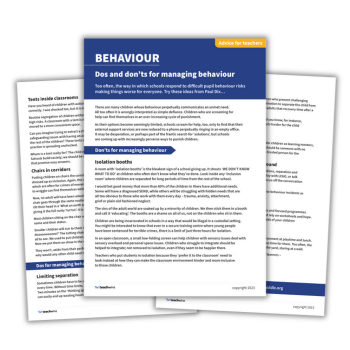

Read more about behaviour management strategies for early years, primary and secondary. Download a free Paul Dix dos and don’ts behaviour resource.