Oracy – What it is and the best classroom resources

Improve pupils’ speaking skills by explicitly teaching oracy in the classroom, with these activities, ideas and other teaching resources…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Unlock the power of effective communication and help your pupils become confident and articulate individuals with the best oracy advice and resources from education experts…

What is oracy?

Coined in the 1960s by British researcher and educator Andrew Wilkinson, ‘oracy’ describes the ability to express yourself fluently in speech.

Over the decades, its role in education has become better understood and more highly valued. After all, what better way could there be to demonstrate understanding than the ability to convey an idea clearly to someone else?

It’s the skilful manipulation of words that forms the bedrock of oracy. English lessons, therefore, are the perfect place to teach this skill. However, oracy is important in all subjects, from explaining your reasoning in maths to responding appropriately to an alternative perspective on life in RE.

Oracy covers many different aspects. These range from basic features such as the volume, clarity, pace and tone of the delivery, to broader considerations such as respecting the audience, listening and taking turns.

Then of course there’s choice of words, rhetoric and content, not to mention the ability to organise and explain your ideas verbally.

Why is oracy important in the classroom?

Research points to a number of ways in which high-quality talk underpins all pupils’ development as communicators – socially, emotionally and cognitively.

It also highlights how placing a focus on oracy in mainstream primary schools could be of particular benefit to pupils with SLCN. These students can arrive at primary school without the language they need to communicate, or even think and reason systematically.

Oracy resources

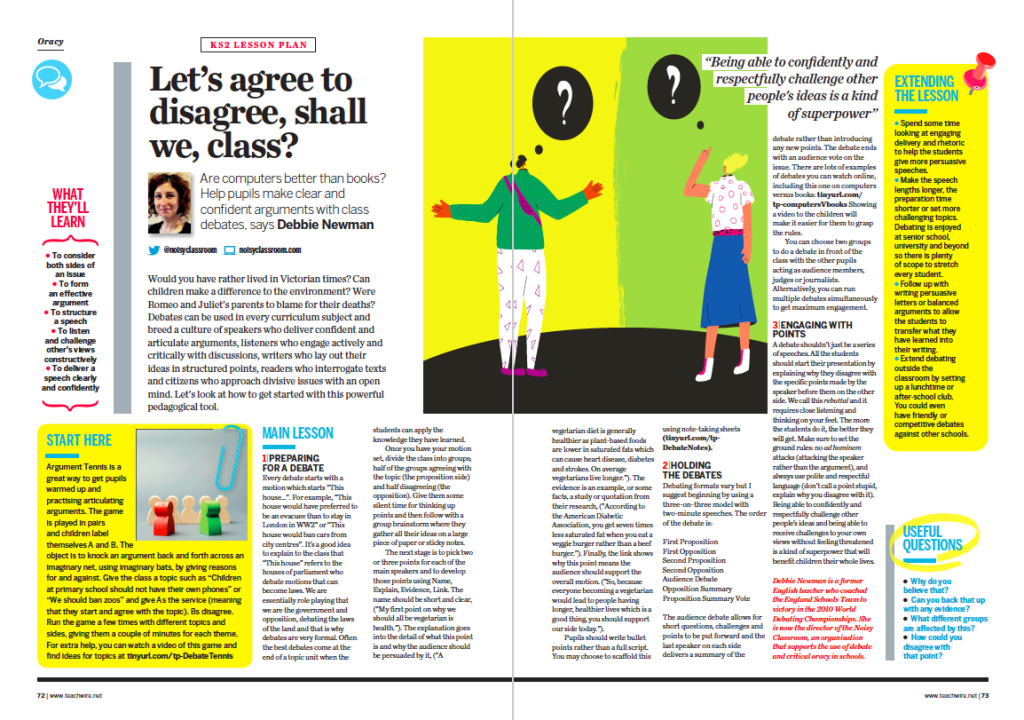

KS2 oracy lesson plan

Are computers better than books? Help pupils make clear and confident arguments with this free KS2 debate lesson plan. Children will learn to consider both sides of an issue and form an effective argument.

Weekly topical debates

First News is a weekly newspaper for young audiences, covering global headlines and empowering children with an understanding of the world in which they are growing up.

Every Tuesday, over at Plazoom there is a free #TopicalTuesdays resource to download, containing a news clipping from First News and a worksheet of related activities to try in your classroom, including an oral debate guide with question prompts.

Past topics include everything from climate change and charity stunts to teacher shortages and the school concrete crisis.

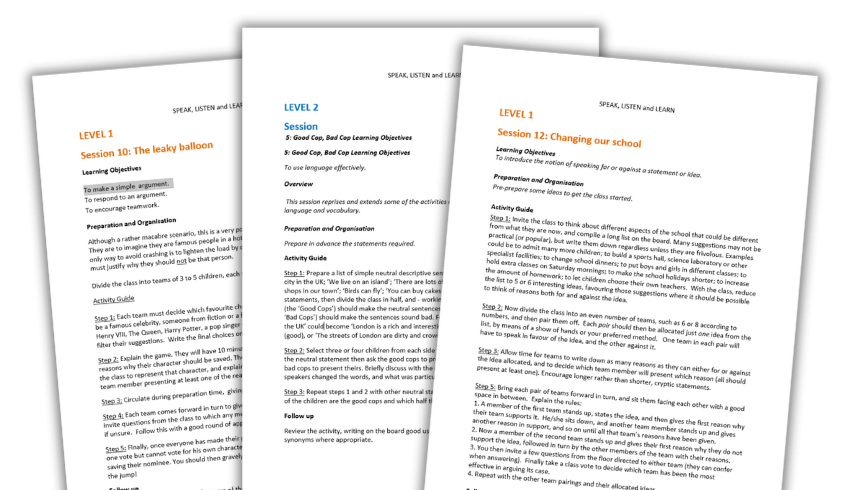

Three speaking and listening activities

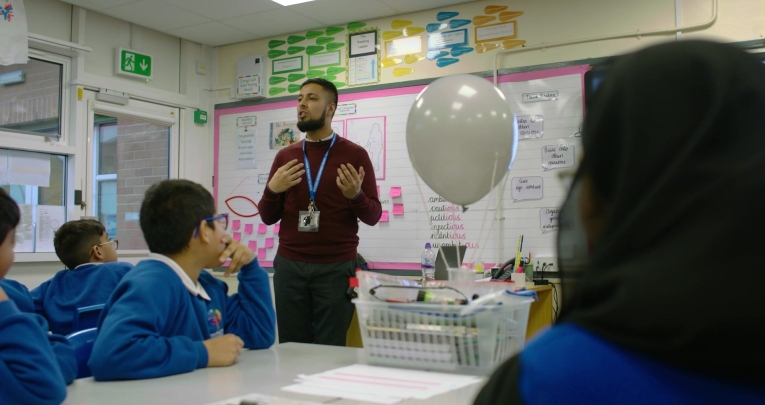

These three activity ideas will improve children’s listening and speaking skills, self-confidence and motivation to learn. There’s a leaky balloon thought experiment, a school improvement debate and a ‘Good cop, bad cop’ presentation activity.

KS3 zombie oracy lesson

This free KS3 lesson plan uses zombies as a hook. Learners will have the opportunity to read and discuss texts – including written, visual and moving image texts – from a range of sources.

Oracy in Action programme

Oracy in Action is a complete oracy programme for primary schools, enabling you to deliver a sequenced, evidence-based speaking and listening intervention across your school.

It’s designed to be a ‘grab-and-go’ programme that you can deploy throughout your school with minimal additional workload. Find out more and download the first lesson plan for free.

Voice 21 resources

Voice 21 is a UK-based organisation set up by staff from School 21, a free school in Stratford, London. The school has pioneered a curriculum model that places oral literacy at the heart of everything it does.

School 21’s oracy approach helped them secure a glowing Ofsted report in 2014, with inspectors commenting on its pupils’, “extraordinary skills in listening, speaking and questioning.”

Find out more about becoming a Voice 21 Oracy School and joining over 900 other schools that are transforming teaching and learning through talk. You’ll receive training and support to embed oracy deliberately and explicitly in your teaching practice and across your curriculum.

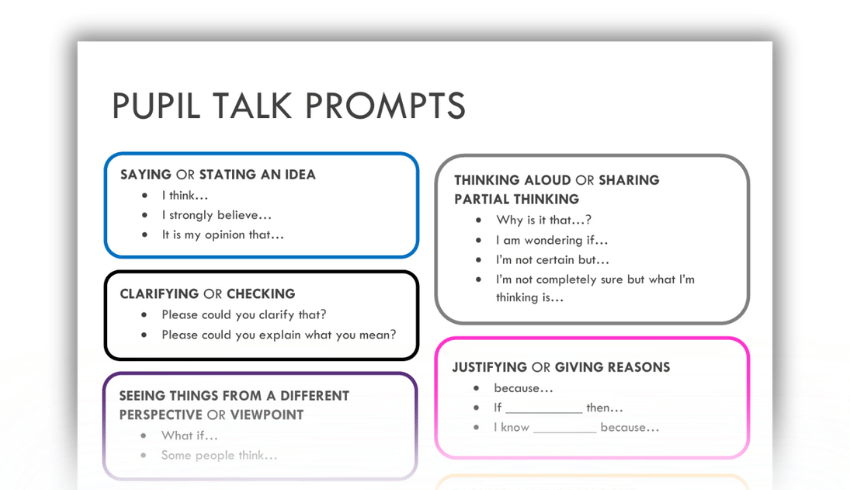

Oracy Cambridge

Oracy Cambridge, based at the University of Cambridge, promotes oracy in schools and in wider society. Find a host of downloadable resources including pupil talk prompts and discussion guidelines.

Seven ways to boost public speaking skills

Help children discover their public-speaking talents with these seven pro-speaker secrets from Graham Shaw that will enhance their confidence and impact.

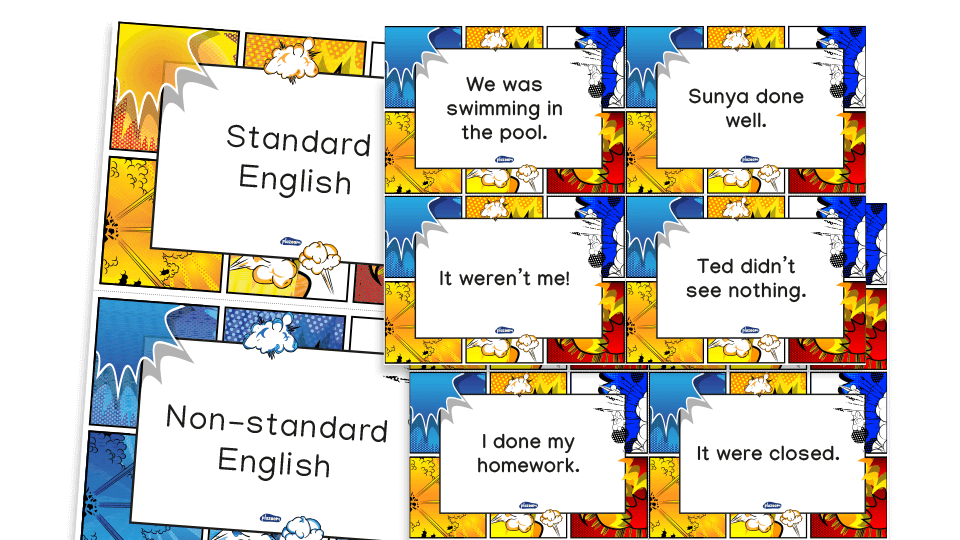

Standard English vs non-standard English

Knowing the differences between standard and non-standard English, formal and informal language, is obviously a key language skill when speaking, whether you’re addressing an audience or speaking one-on-one.

This fun game resource from literacy resources website Plazoom helps pupils get to grips with standard vs non-Standard English.

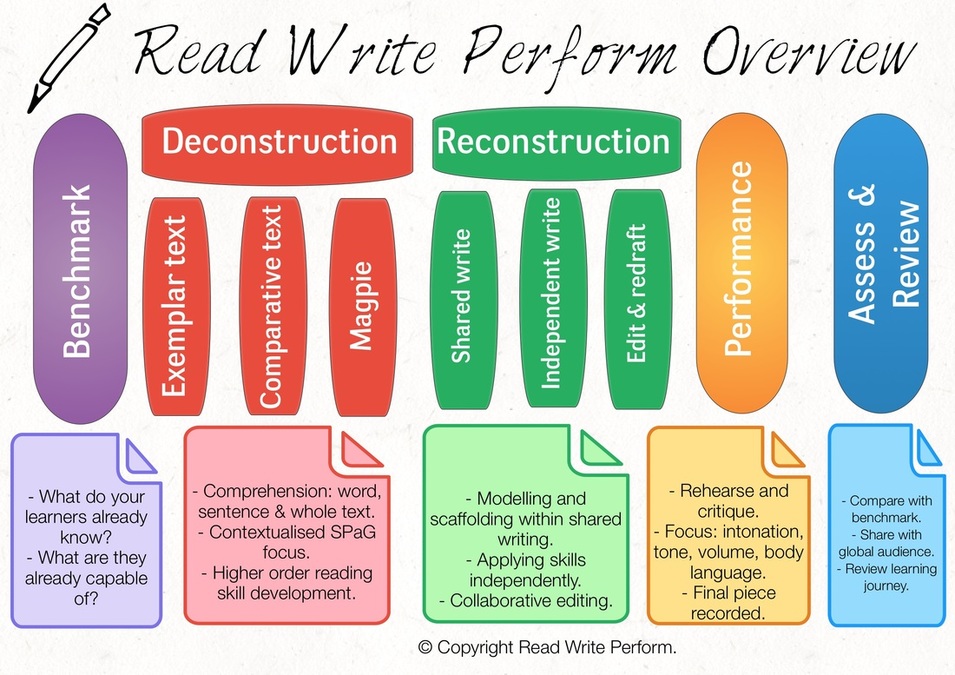

Read Write Perform

Read Write Perform is an engaging approach to teaching English that encourages children to apply what they have learnt in a meaningful and purposeful way in order to embed their learning.

Download resource packs to try it in your school. Each one contains comprehension lessons, writing lessons and performance lessons. The last of these develop reading fluency and improve pupils’ social skills and confidence.

Public speaking activities

Public speaking doesn’t come naturally to everyone, but these fun activities can help students develop the skills they need to succeed.

Using spoken language to explore senses

This KS2 activity uses exploratory learning activities to develop pupils’ spoken language skills. By interacting with a natural environment and taking part in a series of activities that explore their senses, pupils will articulate answers and opinions, give well-structured descriptions and narratives, and participate in discussions.

Easy ways to introduce oracy in primary

By introducing oracy activities on a ‘little and often’ basis, you could have a massive impact on your pupils’ ability to express themselves clearly…

First, set some rules and expectations. For a start, insist on standard English whenever your pupils are talking within a class context. Don’t be afraid to correct them if necessary: “It’s those pencils, not them pencils,” and so on.

That means, of course, that you need to set a good example. Work hard to eradicate any bad habits that you might have developed over the years.

Questions and answers

Make time for short word games as a warm-up activity. There are plenty to choose from, but ones that involve questioning and responding are particularly good for developing oracy skills.

For example, younger pupils love ‘20 questions’ (in which only ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers are allowed) while older ones might enjoy some version of ‘Just a Minute’, the long-running radio game.

A broad vocabulary is an essential part of improving pupils’ life chances. Use oracy activities to help children expand their personal lexicons, perhaps by getting them to explain or define less common words, or even challenging them to include these words in everyday conversation.

Compelling arguments

More interesting speakers make good use of rhetorical devices, such as humour or figurative language. Anyone who has heard a badly-pitched wedding speech will know that using humour effectively is not as easy as it might seem. School can provide a safe space for practising that.

Much the same is true of rhetorical flourishes. Encourage pupils to use techniques such as similes, metaphors and personification when they are speaking.

Of all the oracy skills, the ability to debate effectively is one of the most useful, because it encompasses so many important aspects, from marshalling ideas and information to ‘reading’ the audience.

Include oral debates as part of the planning and preparation for a persuasion or balanced argument writing unit. Or why not make time for a weekly debate based on current affairs?

Sue Drury is literacy lead at Plazoom, the expert literacy resources website.

Hand signals for dialogue

Use active learning gestures to indicate ‘I agree’, ‘I disagree’ or ‘I’d like to build on…’ Decide on a set of non-verbal signals to indicate thinking during whole-class dialogue. Aim for still, silent signals, which are less likely to be distracting than moving or noisy ones.

Some examples could be:

- Open hand resting on heart – I agree.

- Closed hand on heart – I disagree.

- Thumbs and index fingers make two interlocking circles – I have something to say that connects.

- Index finger up – I have a question.

Using them respectfully

Give pupils opportunities to practise these hand signals before you begin using them in lessons.

Discuss how the timing of hand signals matters, and the pros and cons of showing signals while people are talking. Discuss the possible effects of ‘jumping in’ with a disagreement signal when someone is still making their justification.

It’s essential that your class use hand signals respectfully, and that this fits with your class ethos of respectful listening and positive attitude to learning.

RAG cups

This is a powerful tool for assessment for learning. RAG cups are red, amber and green paper cups that some schools make available to every child in every lesson.

The expectation is that children will continuously reflect on their learning, asking themselves ‘How is my learning going?’ throughout the lesson, and using the cups to signal their current thoughts to the teacher and TA.

The different colours are used to indicate the following opinions:

- Red = ‘I’m stuck’ or ‘I disagree’

- Amber = ‘I’m a bit confused’ or ‘I have a question’

- Green = ‘I understand’, ‘I can teach others’ or ‘I agree’.

Give a set of cups to each child; the cups stay on tables at all times. Tell the class to start each lesson by stacking their cups with green showing. As the lesson progresses, they are responsible for changing the colour to reflect their learning status.

During whole-class learning, if you spot a child on amber or red, pause, and use pupil talk to progress. For example, ask another child, whose cup is showing green, to explain.

(The cups develop accountability as well as oracy – children on green are expected to be able to give peer support.) If you see a lot of amber or red, consider alternative strategies, including different ways to explain.

When pupils are working on their own, if peers notice someone on red, they can provide support: “Are you OK, Emeka? Do you need help?”. Likewise, as adults circulate the room they can quickly notice who needs support: “I see you’re feeling unsure, Amy – why are you on amber?”.

Using them in class

RAG cups are brilliant when pupils present work to the class, as children can change their cups if they spot any errors and then explain and make suggestions for improvements.

They can be used during whole-class or group dialogue too, with children using their cups to signal agreement or disagreement.

Make sure you invest time in this strategy to properly reap the rewards, and be consistent with your expectations. This is about children gaining the habit of reflecting on their learning continuously.

Topsy Page works with schools to develop a culture of high-quality dialogue and reasoning across the curriculum. She is the author of 100 Ideas for Primary Teachers: Oracy.

Does Ofsted care about oracy?

Executive headteacher Anthony David considers the extent to which Ofsted cares about speaking, and what that might mean for teachers…

In April 2021, an Oxford-based think tank, The Centre for Education and Youth, published a report on Ofsted’s reporting of oral skills that largely went under the radar.

It aimed to examine whether students’ oracy skills had been impacted by the pandemic, using prior inspection reports as an evidence base. When those reports were analysed, the picture they painted of speaking was mixed, to say the least.

Oracy is clearly something inspectors are sensitive to, with 54% of the reports mentioning speaking in some form, following a steady increase since 2015. However, the emphasis of oral comments was often lighter in tone than those on core skills.

“54% of the reports mentioned speaking in some form”

And while the number of reports referencing oral skills might have grown from 174 in 2015 to 446 in 2018, that’s dwarfed by the total number of Ofsted reports produced each year, which typically amount to ten times that number.

Commentary or judgement?

When it comes to mentions of oracy in key findings, that proportion shrinks even further – from a 2012 peak of 236 reports referencing oracy in their key findings, to just 42 in 2019. It could therefore be argued that Ofsted either isn’t particularly minded towards speaking, or that its inspection process lacks the framework needed to accurately assess oracy in the same way as core subjects.

The latest Ofsted Inspection Handbook references the spoken word as often as reading, deploying a variety of words – including ‘oral’, ‘talk’ and ‘speaking’ – when referring to oracy in varying contexts.

What’s different, though, is that the emphasis is typically on the oral skills of teachers, and how they provide feedback and model language, over how pupils use newly acquired language. With reading, it’s always the child’s capacity that’s being measured.

As such, there’s the risk that any references to oracy skills in Ofsted reports are purely commentary with no particular judgement, whether positive or negative. That said, there seems to be something of pattern in Ofsted reports in that positive comments on oracy typically reflect a teacher’s skill in developing language in the classroom, while negative comments are usually made in reference to resourcing or students’ use of language.

Trending

The spoken word

In this context, it would be easy to conclude that Ofsted aren’t especially minded to assess oral skills – but good schools know that if they want students to be better writers and readers, they need to have experiences that stimulate that.

“It would be easy to conclude that Ofsted aren’t especially minded to assess oral skills”

Students need parameters within which to exercise newly acquired language skills, opportunities to play with words and feel how they sound, and chances to use them in a safe, supportive environment.

Within this context, Ofsted’s interest in the spoken word increases significantly. Much of the Inspection Handbook centres on students being able to speak about their learning experiences. This may well include activities such as organising a campaign or working in support of a charity.

Even book looks have changed, with child conferences and book scrutinies now approached as a single activity. Students bring their books to the inspector and discuss their learning with those books to hand.

What we do know is that overlooking oracy presents a risk for deprived students. Prior to the pandemic, it was thought that students from low-income families heard approximately 30 million fewer words than those from high-income families.

What has yet to be analysed is the diversity, context and opportunities for speaking that higher-income families can access.

The Covid effect

Sadly, from what we’ve been able to observe so far, the pandemic had a significant impact in this area. Students spent prolonged periods during lockdown with little or no access to the kind of casual spoken opportunities that were previously part of everyday life.

Even after they returned to school, students were unable to participate in activities such as singing, performing in class assemblies and shows, or participating in traditional singing games.

Between March 2020 and September 2021, there were significant restrictions on spoken communication. The data we have shows that more than 10% of students continue to miss out on education due to Covid-related absences.

In many ways the situation is worse than ever. The home learning we experienced may have been difficult, but we at least knew that the vast majority of students were accessing learning via remote provision, compared to the current chaotic patchwork of students being in and out of class.

In April 2021, the BBC ran a report highlighting the impacts the pandemic had had on young people’s learning. The list of lost speaking opportunities was stark, spanning a dearth of intergenerational conversations with visiting grandparents or extended family, a lack of social opportunities both in and outside school and fewer chances to practice visual communication, thanks to the wearing of face masks and social distancing.

Long-term impacts

When all this is taken into consideration, we can see that there’s strong anecdotal evidence indicating lower confidence levels among students than might have been expected in the past.

The specialist SLCN firm SpeechLink has estimated that 20% to 25% of Reception pupils will require additional support with their speech.

So far there hasn’t been a similar study examining the speech skills of students at secondary, but my instincts would lead me to suggest that the impact may be just as significant – though the consequences may take years to be felt. There will be some students who manage to bridge the gap, but also a far larger group who won’t.

Key to enriching students’ language and narrowing the spoken word gap is access to resources that focus on language in a safe environment, and give students opportunities to exercise speaking abilities purposefully.

What teachers need to avoid is downplaying students’ adoption of new language. Instead, we should be celebrating the joy to be had in learning new words, and using them to express our ideas and thinking.

Anthony David is an executive headteacher.

Why oracy is a social justice issue

Speech skills aren’t just for future lawyers, entrepreneurs and politicians; they are a secret ingredient to a successful life for all pupils, explains principal teaching fellow, Amanda Corrigan…

As a child from a working-class Glasgow family, words were always mine. My parents left school at 15 to get on with their lives. But they brought us up with books and opinions and lots of talk at home. We had a good vocabulary made up of English and a healthy smattering of Scots.

When I started school, I revelled in further developing these skills and using them to describe my life and my learning. There are many examples of this captured in family tales; my descriptions of the Norway Spruce I hid behind when I was six, or the gory details of the scab on my knee that I shared as my news in Primary 3 (Y2).

I had the words I needed, but, more importantly, adults gave me the space and the encouragement to use them. So when I heard Kier Starmer talking about oracy in 2023, I cheered.

Fighting for your rights

However, I was surprised at the number of journalists who either didn’t know what ‘oracy’ was, or mistakenly reduced it to ‘being able to talk in a way that helps you fit in’. You see, oracy does not only allow young people to debate in school. It’s more than a skill for future lawyers, entrepreneurs and politicians.

Oracy is what will help the children in your class who end up in the criminal justice system to represent themselves well as they explain their circumstances. It is for the children who will have to fight deportation, or for the rights of their brothers and sisters, or for the care their parents need in later life.

“Oracy does not only allow young people to debate in school”

Oracy is a life skill, and is just as much about confidence as about words. It is a social justice issue.

Oracy in the classroom

Back in 2014, the gap in vocabulary use between the richest and poorest children in Scotland at age five was 13 months; my colleagues Edward Sosu and Sue Ellis wrote a report for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation about it.

This marked gap from the outset of a child’s education is unlikely to have improved since Covid. For some children, school is the only place they will encounter a dedicated effort to boost their spoken vocabulary.

Many of you will remember having a word tin when you were learning to read. Mine was an old tobacco tin of my grandpa’s, and helped me add new words to my vocabulary. The books I read now and what I can do with words on paper grew from that tin. It is useful to think of spoken language in your classroom in the same way.

Children build their vocabulary using words. We can teach, explore and practise new, interesting and complicated words in class. When I was a primary school teacher, my classes enjoyed showing off their vocabulary. Even the youngest children could use sophisticated words when they were introduced well.

So, as you embark on your lessons, remember that hidden tin of words that lies deep within each child. As you add to their vocabulary, consider the outcomes of all the children you teach – the good and the bad.

Think about when they might need to use their words to explain their actions, define their emotions and defend themselves, then plan diligently and teach enthusiastically to grow their vocabulary and their confidence to speak.

Amanda Corrigan is principal teaching fellow at The Strathclyde Institute of Education, University of Strathclyde. Follow her on Twitter @ajcorrigan.

Case studies from real primary schools

- Cubitt Town Junior, Tower Hamlet

- Green Lane Primary, Bradford

- Eastwood Primary, Keighley, West Yorkshire

Cubitt Town Junior, Tower Hamlet

“Your children are very well-behaved, but getting them to talk is like getting blood from a stone.” This was the stark feedback from a peer review process with leaders from local schools 18 months ago.

Our children were passive; there simply wasn’t enough meaningful talk in our classrooms. This conclusion, which seems so obvious to us now, set in motion a process of change, the impact of which has taken us by surprise.

Many schools in Tower Hamlets work with a large proportion of children from backgrounds without a high-quality model of spoken English at home.

Unfortunately, with so much to cram into the curriculum and the twin demands of improving results and being ‘Ofsted-ready’, there has been little room for robust teaching of spoken language and communication skills, known increasingly as ‘oracy’.

We came to the conclusion that spoken communication skills were the missing link in our curriculum and decided to promote oracy to have equal standing alongside maths and literacy.

In the middle of the ‘Ofsted window’, this was certainly a risk, but given that we felt it was what our pupils needed, one that we were more than willing to take.

A comprehensive approach

We first developed a comprehensive approach to teaching oracy. We decided that oracy skills should be taught in stand-alone lessons as well as being woven throughout the curriculum.

Every class created discussion guidelines to hang on the wall to model the expectations of talk, including using positive body language, listening intently, taking turns and agreeing and disagreeing politely.

Talk is now scaffolded in a similar way to writing, with sentence stems and word banks to support less confident speakers. Each classroom has an oracy display and we have termly school-wide oracy events such as persuasive speech competitions and poetry slams.

We have also replaced traditional assemblies (which seem not to have changed much since the Victorian times), with dialogic assemblies, carried out in circles.

These are opportunities for children to consider philosophical ideas, debate topical issues or have discussions relating to a range of stimuli. Teachers and additional adults act as facilitators to the discussion and all children are expected to talk, in pairs, trios and to the whole group.

We knew that if we wanted oracy to be successfully embedded within our curriculum, we would need a whole-school approach. We ran two full-staff inset days, and have had numerous staff meetings exploring approaches to teaching oracy.

These included support staff and midday meals supervisors, who had additional training on the language of conflict resolution. A collective consciousness about the importance of talk was beginning to grow.

Spreading the word

Oracy now sits alongside literacy and numeracy as an equal partner in our curriculum. The impact of this change has been dramatic.

Pupil voice surveys point to an increase in confidence, with a significant jump in the percentage of children who identify as ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ confident in speaking to partners, in front of the class and in assemblies.

This mirrors our own observations and those of external visitors, including Ofsted, who have commented on the confidence and impressive spoken language skills of our children. Quite a contrast from the passivity observed a year before.

Word has spread of our success so we launched an Oracy Hub in Tower Hamlets. Over 20 primary schools have signed up for a year of training, sharing practice and raising the profile of oracy education across the borough. Watch this space… or should I say listen?

Nicky Pear is an assistant headteacher and oracy lead at Cubitt Town Junior School in Tower Hamlet.

Green Lane Primary, Bradford

At this school a high number of pupils arrive with SLCN, often because of limited development in a language other than English (meaning these pupils additionally have EAL).

The school’s leadership team consequently sees spoken communication and social interaction as fundamentally important, with one teacher joking that anything else is “icing on the cake”.

Every teacher in the school uses Makaton sign language in their day-to-day interactions with the children because they believe that signing helps to reinforce new and existing language while providing a bedrock for communicating within and across all areas of the curriculum.

The benefit of this approach is not the learning to sign per se, but rather that it helps children communicate with their teachers and peers with greater confidence, and to explore and deepen their understanding of key ideas and concepts during lessons.

This appears to be an effective strategy because it is applied universally. There is an expectation that all teachers and pupils will use it, not just those in need of additional support. (Although the school’s teachers can and will provide additional support if necessary).

Newer staff at the school mentioned that learning to sign could be an intimidating prospect. However, the weekly training sessions held by the school meant they could pick it up quickly.

Eastwood Primary, Keighley, West Yorkshire

Eastwood Primary works with a number of children who present SLCN upon entry. One way in which the teachers support these pupils is by defining and revisiting common ‘ground rules’ for talking and listening. These include, for instance:

- Not interrupting classmates while they are speaking

- Making eye contact when speaking or listening to someone

By bringing oracy to the fore, the pupils become more aware of how they speak to one another. As they move through the school, they therefore become increasingly able to support one another and collaborate in discussing ideas or solving problems.

This helps to ensure that all pupil contributions – including from pupils with SLCN or other additional learning needs – are invited and supported by teachers and other pupils.

Teachers at Eastwood sometimes film parts of their own lessons and watch the footage back with their classes. After reflecting upon their verbal interactions, the pupils sometimes ask to revise their class ground rules.

One teacher told us that her class wanted to place greater emphasis on the importance of inviting and supporting contributions from the quieter members of their groups.

Thanks to Will Millard for the above two case studies. Will is an associate at the policy research and campaigning organisation LKMco and a former English teacher.