Emotional literacy passport PDF

KS1, KS2

Years 1-6

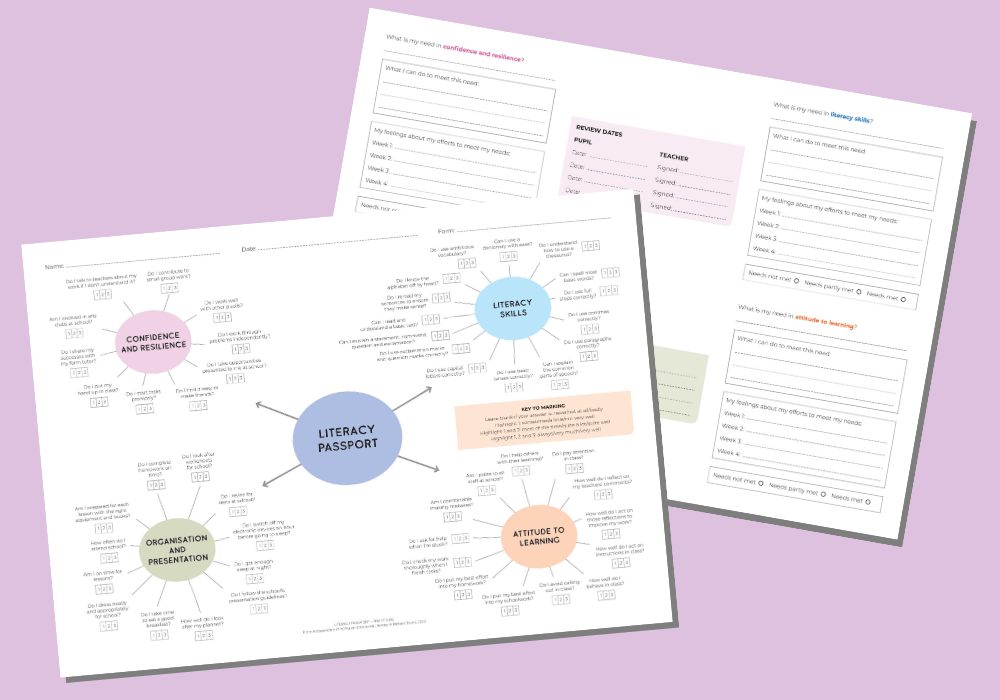

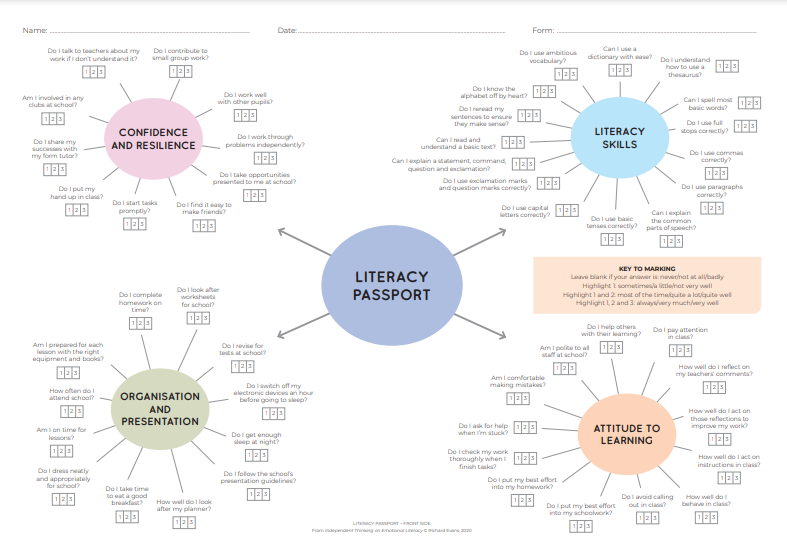

This emotional literacy PDF is a tool designed to promote pupils’ confidence and resilience, their skills of organisation and presentation, and their attitude to their learning – all through improved understanding of themselves.

How to use this emotional literacy resource

This emotional literacy passport is a tool to promote pupils’ confidence and resilience, their skills of organisation and presentation, and their attitude to their learning – all through improved understanding of themselves.

First decide if the emotional literacy passport’s questions chime with what you also sense are the more immediate needs of your pupils – the ones struggling not just with their literacy.

Review each question and decide if you wish to change or delete any, to better suit your pupil. If 50 questions are too many, remove some and keep those of most value. If there are more age-appropriate questions you can ask, adapt them to suit.

Next, arrange a one-on-one meeting with your target pupil. Equip them with a highlighter and invite them to fill out the passport, discussing questions as you go. It’s now your turn to listen and be the learner, and your pupil’s turn to be the teacher.

Given time, space and a little cajoling if necessary, they’ll tell you what it is that prevents them from learning.

Detailed discussions

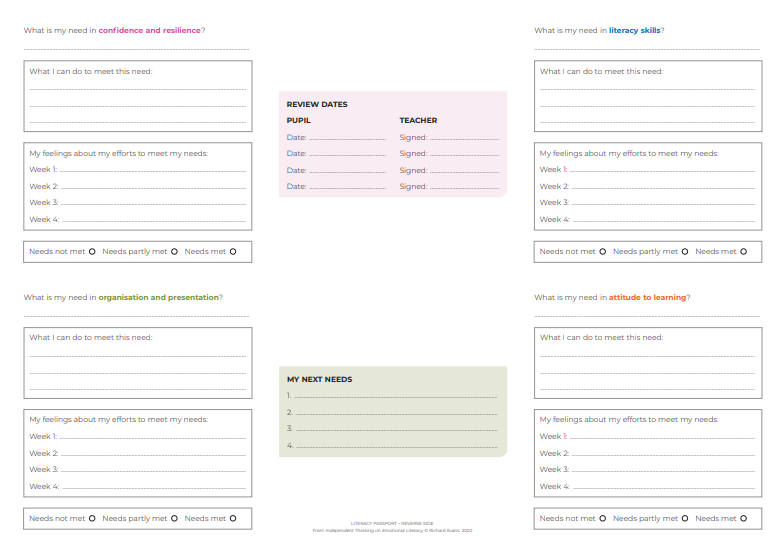

Ask your pupil to circle one question per section – the need they say they would most like to work on – and ask them to transfer it to each of the four ‘What is my need in …’ sections on the second page.

One question at a time, discuss in detail the section entitled ‘What I can do to meet this need?’.

Dig deep for the underlying reasons why this need isn’t being met and help your pupil come up with strategies they can practise to start to change this situation.

For example, for a shy non-contributor in class, can they tell you what it feels like to put their hand up? Are those feelings akin to others they’ve had in life? How have they dealt with those? Can you share what it felt like for you when you were a child, or feels like now?

By both sharing your thoughts, you may then be able to establish ideas together about what might help break the cycle.

For example, your pupil may agree to putting their hand up once a week, at a time when they feel most comfortable, or jotting down answers on a pad of paper instead.

Gradual process

Regardless, it must be their ‘how to’, tailored to their needs, at a pace they’re happy with. It may take several weeks to make even a small amount of progress but the key is, with your help, they’re trying. And with trying, and honest appraisal, comes learning.

Continue to meet once a week to discuss and fill in the ‘Feelings about my efforts to meet my needs’ section.

Listen carefully and reserve any judgement. In fact, even where effort appears minimal and feelings are negative, encourage your pupil to record them.

A ‘proud of myself’ is no more important than a ‘disappointed I forgot’ or even a ‘don’t really care’.

Remind pupils that it’s normal to make a slow start or forget or feel apathetic. But still encourage them to discuss ideas that would help them to make better efforts next week for what is, after all, their chosen need.

For example, can your pupil set aside five minutes at the end of a piece of work to check it? Can they put down technology an hour before bed?

Ask pupils to record the efforts (or otherwise) that they’ve made, the impact, and the feelings they’ve experienced as a result.

Finding time

After week four of your meetings, discuss with your pupil whether their needs are ‘not met’, ‘partly met’ or ‘met’.

Resist the urge to gloss over difficulties or obstacles your pupil may be experiencing. An unmet or partly met need is okay: it’s the process, more than the evaluation, that is of most use to them.

Make these decisions together and have your pupil include any unmet or partly met needs in the section entitled ‘My next needs’.

Complete the list by turning to the front of the passport for pupils to find and circle their next most pressing needs.

You have now completed one round of the passport and are ready for the next, whenever your schedule permits.

This whole process isn’t casually slipped in alongside an average classroom teacher’s job, or that of a TA, mentor, head of year or LSA.

No matter your role, if you work in a school, you’ll be short of time. And this is clearly a process that necessitates time.

But if you believe in the approach – teaching emotional literacy in order that pupils may access reading and writing literacy (and all the other subject skills besides) – then you are the who: the person best placed to identify the pupil, secure the time, listen and cajole, aid and support, listen again, and take your pupil through the process.

Afterwards, instead of just being able to identify nouns and adjectives, pupils should also be able to do the vital things that can lead to so much more than just doing well at school: making friends; getting a good night’s sleep; finding ways to improve a myriad of behavioural issues.

By listening and showing them how, these difficulties don’t need to be an unwelcome companion on pupils’ journeys through school and beyond.

Why is emotional literacy important?

Teaching any given school subject in isolation without pupils also gaining a good handle on their own emotional literacy – what makes them and others tick; how they can adapt themselves for the betterment of both – has limited long-term benefit.

Benefits for literacy teaching

To access literacy teaching so that it sticks and has longevity, it helps if struggling pupils are also feeling more confident and resilient, are reasonably organised, and are able to show a good attitude to their learning.

Their attention to these three sections on the passport will automatically help them to make inroads in literacy, as well as in other disciplines in class.

Accessing literacy teaching is also, of course, about practice: just by discussing, reading and recording thoughts on the passport each week, pupils will be practising key literacy skills.

Furthermore, as part of the literacy skills section, pupils will be developing one such skill at a time. Find resources, work with other teachers and model good examples to help your pupil develop key skills, ranging from remembering the alphabet to using ambitious vocabulary.

In each case, dig deep together to find the root of the blockage and possible solutions: is the middle bit the confusing bit of the alphabet? And if so, would pictorial cues or mnemonics or rhyme and repetition help make it clearer?

As with all of their other chosen needs, reassure pupils that you will be happy to support them as they think up and practise ways, tailored to them, to improve and grow confidence in this area of personal need.

Richard Evans is a secondary teacher with a particular interest in helping pupils who struggle with literacy. Editable versions of the literacy passport and other passports, including a reading one, are available for download when you buy Independent Thinking on Emotional Literacy.