How to use a TA effectively in the classroom

Teaching assistants – beloved by teachers, essential in schools. But where, when and how should they be working with pupils?

- by Sara Alston

- SENCo, author and SEND consultant with 35 years of experience Visit website

We’ve all had that feeling: overwhelmed in the classroom, three different groups of children all needing attention at once, becoming frazzled, and then – you remember your teaching assistant. Your saviour. Your blessed knight-in-educational-armour.

The thing is, a TA is expected to perform many roles, often focusing on specific pupils. This means that for much of the time, TAs are often either passive, focused on behaviour management, or absent from the classroom, completing admin tasks or leading interventions.

These tasks detract essential time from TAs providing whole-class support such as using visuals to support children’s understanding of language, focus on learning and access to instructions; supporting with focus and attention and/or sensory needs, including through fidget objects and movement breaks; and acting as an ‘extra pair of eyes’ identifying who is or is not accessing the learning.

In The Inclusive Classroom, Daniel Sobel and I looked at how to promote inclusion by focusing on small tweaks and adaptions that could be implemented throughout five phases of the lesson; effective TA deployment is a key element.

Phase one

Entering the classroom and preparing to learn.

Communicating with your TA when entering the classroom – and the role they play in supporting pupils through this transition – can be problematic due to the fact that many TAs arrive with the children.

A better way to utilise a TA’s expertise would be to have them ‘meeting and greeting’ the children alongside the teacher (saying ‘hello’ and making eye contact supports effective relationships and enables adults to make a quick assessment of children’s wellbeing and readiness to learn); providing a personalised ‘meet and greet‘ for those who need to come in earlier or later than their peers, or complete a set activity to make them feel safe in the classroom; and preparing and reviewing personalised visual or written timetables for children who need them.

Phase two

Delivering instructions and whole-class engagement.

Too often, TA support means that children are taken out for interventions during the delivery of instructions, so they miss this vital part of the lesson.

As a result, they start their independent work at a disadvantage. Alternatively, a TA may need to listen to the teacher’s input to understand learning that they will shortly be expected to teach and differentiate. During this time, a TA could:

- model learning behaviours and strategies;

- support children’s responses to questioning. Oral rehearsal allows a child to ‘practice’ their response before sharing, reducing anxiety so they are more able to focus, listen and contribute ideas;

- use visuals and prompt to support understanding and focus.

Phase three

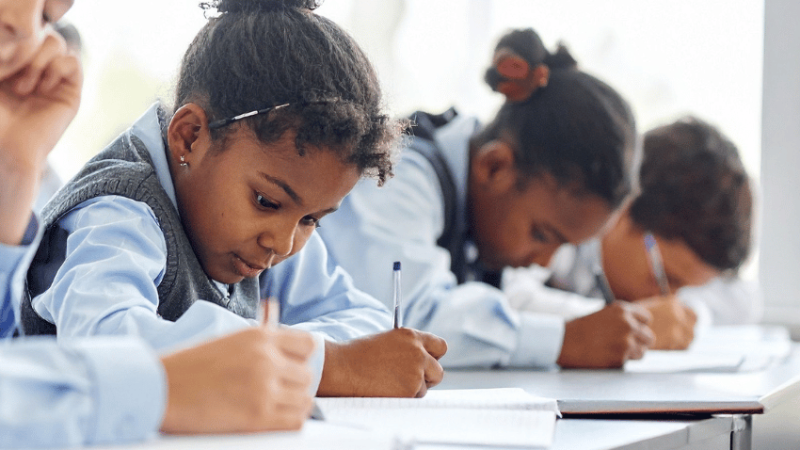

Individuals working as a class.

At this point in the lesson, many TAs ‘take ownership’ of their group – often the less able or those with SEND – and lead their learning. However, this can quickly become a model of ‘segregation’ where the most vulnerable learners are separated from their teacher and their learning is directed and managed by the TA.

Alternative methods of TA deployment include ‘helicopter’ support, where the TA provides a child with a prompted start, models what the child needs to do and scaffolds the first calculation or sentences so the pupil doesn’t face a blank sheet.

Then they can work independently before the TA returns and provides further support in a repeated cycle, rather than the TA being ‘velcroed’ to a child’s side. This promotes the pupil’s independence and enables the TA to work with others.

Another approach is ‘flipped’ support, where the TA roves through the class, while the teacher sits with an individual or group, scaffolding and breaking the task down into short segments.

Where TAs are working with individuals or groups, it is important that they are prompting and scaffolding learning, not simply correcting or providing answers so that children can complete tasks. This could include:

- structured scaffolding of the task – by asking the child what they need to do next and what they already know, the TA can move the student towards greater independence;

- supporting children with the lesson admin, e.g. writing the title or sticking in worksheets so that they can focus on their learning;

- using visual checklists, now and next cards, and task management boards to support children to identify and plot their way through lessons;

- supporting and modelling self-talk so children can identify the stages and structure of their learning;

- the provision of concrete resources and apparatus;

- supporting the use of IT to support children’s recording and reading. Too often an adult either scribes for a child or writes while the child copies. This neither promotes the child’s skills or independence;

- provide encouragement and motivation for children through short-term rewards and ‘live’ marking and feedback.

Phase four

Group working.

It can be easy for adults to take a back seat during group work, but for many children, working with their peers adds a layer of anxiety and difficulty to a task.

Asking them to work with others means managing academic and social learning simultaneously, making both more difficult. Furthermore, being part of a group makes a child’s difficulties more visible to their peers.

This means that the teacher and TA need to be actively involved, by ensuring that children understand that they are part of the group and what their role in it is; facilitating interactions in team or partner work (it is important that adults promote interaction between children and don’t replace it – taking the role as the child’s partner can become a barrier to their inclusion); and providing learned scripts, sentence stems and support for taking turns.

Phase five

The last five minutes.

At the end of the lesson or day, the TA can become so involved in tidying up, preparing resources or moving to the next class that their interactions with children are fleeting and focused on organisational issues. However, support at this point is key to facilitate a child’s readiness for the next phase.

The use of individual time checks and clarifications about the expectations for their work can support children to finish their learning tasks. For this to be successful it is important that the TA and teacher are consistent, so as not to confuse children and undermine each other.

It’s also important to support children to evaluate their learning – many struggle to identify either what they have done well or how they could improve. Lastly, provide individual checklists to help children manage their belongings.

The various key roles of the TA throughout the lesson should be adapted to meet the needs of each class. While the teacher remains in charge, they should be able to swap roles with the TA as needed so that all children receive both focused support and quality teacher time.

But for this to be effective, there needs to be good communication, and the TA needs to be in the room and engaged, rather than completing tasks elsewhere.

Sara Alston is an independent consultant and trainer with SEA Inclusion and Safeguarding, and a practising SENCo. Follow Sara on Twitter @seainclusion