How to manage a mixed-ability maths lesson

Do not assume that grouping similarly able pupils together is the only way for all pupils to achieve mastery, says Suzanne Terrasse…

Strategies for behaviour management are top of most teachers’ wishlist. How do we keep students engaged, learning and well-behaved all at the same time?

Ofsted requires it, appraisals depend on it, but it can be a challenge – especially in maths. Here’s some tips to help you support and challenge in every lesson.

Mixed tables work best

If, in the interests of differentiation, you think it will be easier to plan with a top table, a middle table and a bottom table – which can only be based on previous attainment and will necessarily therefore limit potential – you are setting up most of your class for demotivation and lack of progress from the start.

Even very young children know when they have been put on the ‘low ability’ table, and this affects their self-esteem dramatically. It is far better, in subjects like maths, to group advanced learners with their struggling peers.

Advanced learners will model correct thinking, encourage discussion of concepts and deepen their own understanding as they explain to their less confident peers.

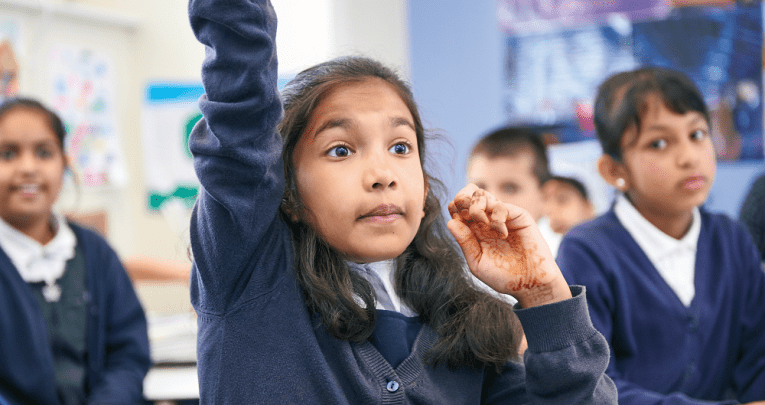

Ask the right questions

Open-ended questioning helps pupil engagement. We all know that to enable pupils to progress in English, especially to deepen their understanding and analytical abilities, we need to ask the ‘who, why, how, where’ questions. Maths is no different.

Asking the following questions, which support the development of metacognitive skills, allows active learning to take place:

- How does this work?

- Who can find a way to…?

- Is that right?

- Is there another way to do this?

The pupils are all working on discovering a method to solve a problem, and, at the same time, they are appraising the method a peer has discovered. This maintains a high level of concentration in pupils for much longer as they are actively engaged and interested in the process. Pupils love marking each other’s work, and this is no different.

As maths mastery expert Ban Har says: ‘We agree to listen to our friends, but we do not necessarily agree to agree with them!’ Critical thinking is thus developed and, without much teacher effort, better classroom behaviour for most students will be achieved.

Pace is crucial

Small children cannot concentrate for extended periods. Some studies estimate that listening time should be limited to a child’s chronological age plus one. So, a five-year-old child can concentrate for up to six minutes at a time. A lesson should include plenty of time for exploration, discovery and playing with concepts.

Breaking down a lesson into component parts will greatly assist behaviour, as pupils remain engaged and learning throughout the lesson. Presenting a topic through questioning engages pupils and helps them develop creative and critical thinking as they come up with multiple methods to solve a problem, and then assess whether these are valid.

Children can debate their solutions with the rest of the class, led by the teacher’s questioning, before working in small groups or pairs to play with the concepts introduced and explore textbook examples under the guidance of the teacher.

Next, they can write about what they’ve learnt in their maths journals, becoming maths storytellers in the process and deepening their understanding of the ideas explored.

Finally, children can work individually in their workbooks, to practise what they’ve learnt, working at their own pace, to grapple with a range of differentiated problems which support learning and push the limits of their understanding.

Trending

Organise your resources

A well-organised classroom is a boon to teachers. Small children (and bigger ones too!) often struggle to locate resources quickly, bring them back to the table, set them up and get on with the task in hand.

A folder or basket arrangement where each pupil, or pair of pupils, has their own folder or basket of frequently used resources, already set up before each lesson, together with the relevant textbook, maths journal and workbook, can save much time and fuss.

Think about the pairings. Do not assume that grouping similarly able pupils together is the only way for all pupils to achieve mastery. A more creative pairing, considering different abilities, concentration levels and personalities, can be far more effective.

Both students can learn from each other and often, a calmer classroom will ensue as a student who is more able mathematically learns from a calmer and more expressive peer and vice-versa.

Noise isn’t always bad

It is often perceived that a noisy classroom is out of control. This is not always the case. Constructive noise is a sign of debate, of the productive exchange of ideas and confident learners.

The test should be whether the noise stops when the teacher is ready to move the class on. If it does, then there is no problem with noise. Within the classroom of an effective teacher, pupils will spend much of their time discussing the work, comparing solutions and working in small groups.

Of course, the teacher will be circulating to monitor and assess the level of learning that is taking place, inputting where necessary to keep students on track, to extend or to support.

Notes from the chalkface

Alex Laurie and Emily Downing from St James’ C of E Primary School, Enfield, discuss their approach to behaviour in the maths classroom…

We sit our children in mixed ability groups of four. This allows for more mathematical conversation which, in turn, moves children forward in their learning. Groups of six can be daunting to struggling or shy learners and, especially in Y1, the tables are simply too big for the children to engage in conversations as a table, so they choose, instead, to talk only to their partner which limits the opportunity for deepening understanding.

Storing resources can be a struggle. We have found using ‘maths boxes’ for each table extremely useful. Inside we put textbooks, concrete manipulatives and a range of other resources such as number lines and blank diagrams. Throughout the year as we learn new concepts and use new resources we add to or remove from the box appropriately. This means children have access to a range of resources to support their learning throughout the lesson.

Our maths lessons can be loud, and messy! We encourage the children to use a variety of different resources and refer to their textbooks throughout the lesson. They are excited to discuss new concepts and the volume in the classroom can quickly increase. However, to maintain control it is important to have a quick tidy up routine. We assign monitors to assist in this. It is also important to have a class signal (we use a rocket noise) that indicates it is now time to listen to the teacher.

Suzanne Terrasse is commissioning editor at Maths – No Problem! (@mathsnoproblem), producer of the only textbook on the DfE’s list of recommended textbooks for schools on the maths mastery programme. It was also named Education Publisher of 2017 by the Independent Publishers Guild.