Maths anxiety – Strategies to boost pupils’ confidence

These simple changes can have a positive impact on students suffering from maths anxiety…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Maths anxiety is a deep-rooted societal issue, but educators are perfectly positioned to make a positive difference...

We’ve all observed them in maths lessons. The student who struggles to settle, seems distracted or disengaged while protesting that the subject is, ‘Booooooring…’. The learner who finds it difficult to answer questions on the spot and opts for the easiest answers every time. The student who rarely ever hands their homework on time – if at all.

And then there are the friends, colleagues and parents who are always quick to opine, ‘I hate maths. Dreadful subject. I’m terrible at it…’.

You know those people. You’ve met them. You may even, whisper it, be one yourself.

This anti-maths mindset is a stifling one that restricts the potential of children, young people and adults everywhere. But it often masks a far deeper issue – that of maths anxiety.

The good news is that there are some simple changes we can all try and make, at both a whole-school and classroom level, which will undoubtedly have a positive impact. More importantly, they are all examples of good practice anyway, regardless of the pupil or subject.

What is maths anxiety?

The term ‘maths anxiety’ has been around for about 50 years, yet there is still surprisingly little understanding and training given to it in schools.

The Maths Anxiety Trust defines it as a “negative emotional reaction to mathematics, leading to varying degrees of helplessness, panic and mental disorganisation that arises […] when faced with a mathematical problem.”

Academic Sue Johnston-Wilder defines maths anxiety as “a negative emotional reaction to mathematics that acts as an ‘emotional handbrake’ and holds up progress”.

Research from the Maths Anxiety Trust has shown that 23% of parents have a child who is experiencing maths anxiety. 20% of adults in Britain also experience anxiety when faced with a maths problem.

Another study carried out by Sian Beilock, professor of psychology at the University of Chicago, showed that students start to experience worry and fear about doing maths as early as Key Stage 1.

“Students start to experience worry and fear about doing maths as early as Key Stage 1”

As maths consultant Mike Askew points out, we sometimes underestimate how ‘at risk’ children can feel in maths lessons.

He says, “While a range of opinions on a story might be welcomed in an English lesson, the sense that mathematical offerings are going to be judged on whether or not they are correct can make children anxious about being called on.”

The severity of maths anxiety can range from a feeling of mild tension to experiencing a strong and deep-rooted fear of maths.

How does maths anxiety affect students?

Maths anxiety elicits a fight-or-flight physiological response, although maths-anxious individuals themselves may not actually be aware they are experiencing it.

While we can’t observe the thoughts of our pupils, we can observe their behaviours. Potential characteristics of maths anxiety include:

- avoidant, defiant or ‘lazy’ behaviours

- underachievement or poor achievement

- anger

- frustration

- helplessness

Unfortunately, some teachers will see the symptoms of maths anxiety as indicative of poor behaviour and seek to address them by way of disciplinary solutions, but this can actually compound learner disengagement even further – by making maths feel intimidating, punishing, and simply ‘not for them’.

Maths anxiety doesn’t just affect mathematics achievement levels. Research has repeatedly shown that maths anxiety can have a long-standing negative impact on stress levels, self-esteem, management of finances and social mobility.

- Choose positive words that encourage curiosity and exploration in the subject

- Avoid black-and-white statements that tell learners there is only ‘right’ or ‘wrong’

- Reassure students of the importance of making mistakes when learning new concepts

- Make space for inclusive group discussions in class

- Emphasise the diversity of the subject, its learners and pioneers

- Try to never put a student on the spot in front of others

- Steer clear of punitive language that can trigger a handbrake on learning

- Use real-life, relatable contexts that speak to your students’ experiences

- Invite collaboration with leading maths lovers in your local community and the wider maths sector

- Highlight the universal importance of the subject in your students’ lives – as young people now and adults in future

Maths anxiety and high achievers

Maths anxiety does not discriminate between ages, genders, maths ability or complexity of maths work. It’s definitely not something that just affects lower-ability pupils.

In fact, there appears to be a higher incidence of maths anxiety among average and higher ability pupils – something that is possibly attributable to the risk factors of embarrassment or fear of failure.

Findings published in Math Anxiety, Working Memory and Math Achievement in Early Elementary School show that lower-performing students are not impacted by anxiety, because of the simple techniques they have learned to use over the years, such as counting on their fingers. Therefore, their performance isn’t so markedly affected when they feel under pressure.

What causes maths anxiety?

Risk factors for pupils experiencing maths anxiety include:

- adults passing on their own anxiety

- not experiencing success

- negative experiences (such as public embarrassment or receiving a poor mark)

Time pressures on tasks, and poor quality or inconsistent teaching (such as different methods being used between staff members or between home and school) are other potential causes of maths anxiety.

Negative thinking patterns and attitudes towards maths, and fears around embarrassment, failure or being judged can also cause maths anxiety.

“Poor quality or inconsistent teaching [is another] potential causes of maths anxiety”

A study published in ‘Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences’ carried out by academics at the University of Chicago revealed that female teachers with maths anxiety can inadvertently fuel the stereotype that boys are better than girls at maths.

In primary schools, where teachers are not always subject specialists, it is easy for their lack of confidence in basic mathematical skills to be passed on to girls.

The study showed that girls’ understanding of maths was ‘significantly worse’ after a year of being taught by a ‘maths-anxious’ teacher. And with the vast majority of primary school teachers being female, this is an important consideration.

How to help students with maths anxiety

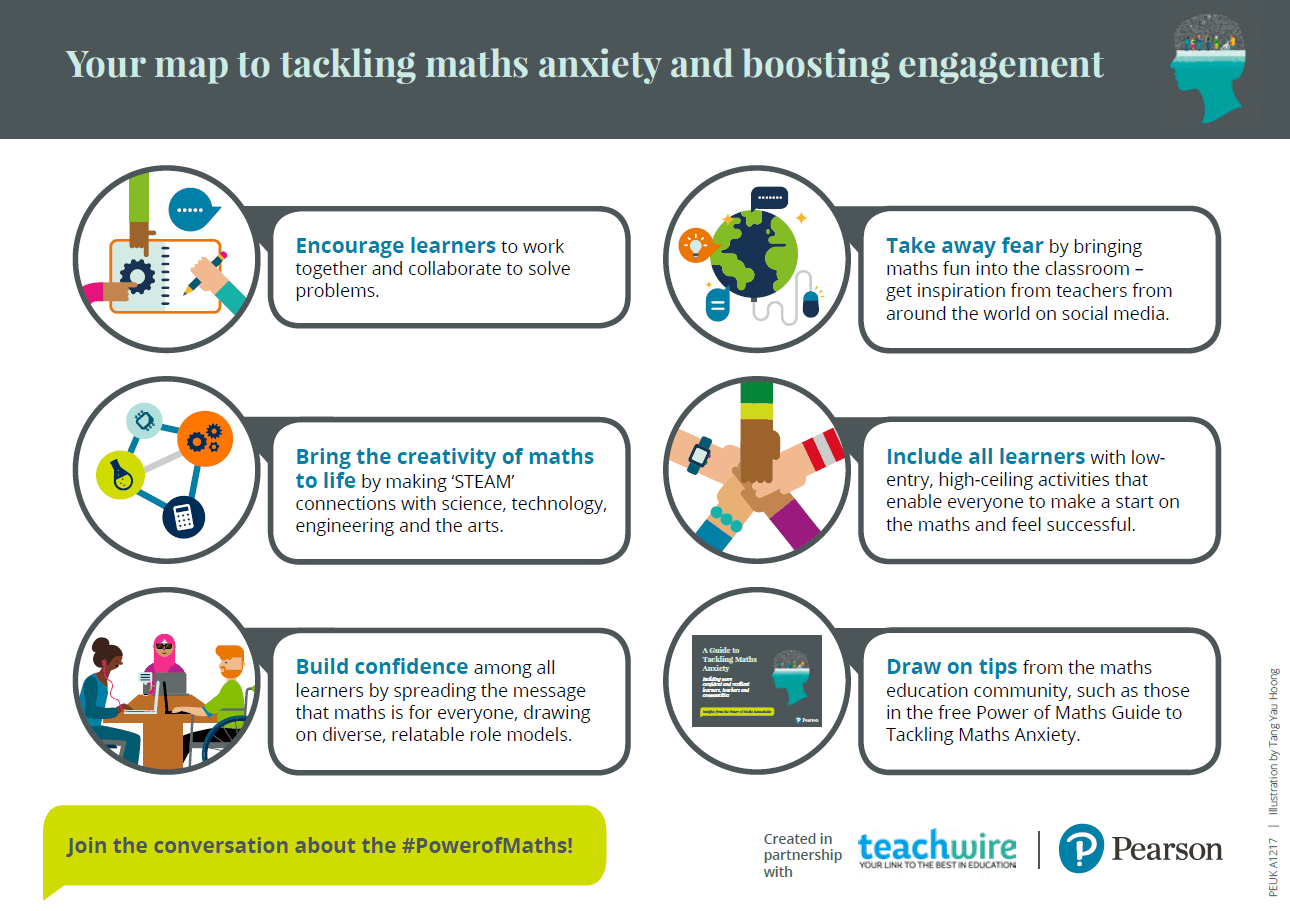

Low threshold, high ceiling activities

Use more ‘low threshold, high ceiling’ activities to consolidate learning or explore new concepts (nrich.org has some good activities and articles relating to this).

Tasks that are perceived as a ‘low threat’ by pupils, due to their simple, accessible nature, allow all children to engage. The ‘high ceiling’ allows pupils to explore the topic as far as they are able to. Pace can be set by the pupil themselves and progressing through the activity is self-motivating.

Everybody working on the same activity reduces that ‘comparison’ and ‘ranking’ ethos that can take place among children.

Utilise edtech

Delivering maths through an edtech platform that uses images, encourages pupils to make informed ‘guesses’ and makes it fun when the answer isn’t exactly right, can instil a joy of mathematics that could remain with them throughout the rest of their lives.

Use pupil and teacher questionnaires

Questionnaires for students and teachers can be useful tools for understanding the cause and scale of maths anxiety in your own context.

Re-run the questionnaire at intervals to monitor the issue, indicating the success of any initiatives and informing new strategies.

Surveys can range from simply asking students to anonymously rate their anxiety when they are asked a maths question from 1–10, to more detailed questions for staff.

Intoduce the growth zone model

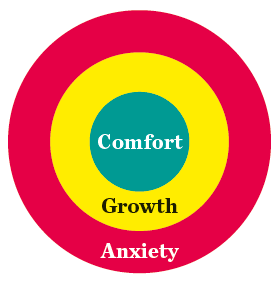

The growth zone model

The Growth Zone Model by Lugalia et al (2013) gives a framework for learners to name and communicate their feelings, helping to reduce anxiety and build resilience.

- The comfort zone: Learners work on familiar tasks independently, building their self-confidence and providing opportunities for practice and automaticity

- The growth zone: New learning happens here, it’s safe to make mistakes, get stuck, require support, and find activities challenging and tiring

- The anxiety zone: Here, what is being asked is not within the learner’s reach at that moment. The learner starts to experience threat rather than challenge, stress increases, cognition decreases, and little or no useful learning takes place

Directly introduce students to the framework and encourage them to use their own words to describe their feelings when faced with different situations, such as feeling challenged or comfortable with maths activities.

Students can then place an object on the colours of the model to indicate their emotions. This will help them to be more aware of their emotional responses and allows you to better understand when to challenge learners in the ‘comfort zone’ with a question or support learners in the ‘anxiety zone’.

Embedding this model supports students to effectively manage their emotional response to learning maths from the start and position them to confidently tackle high-stakes exams in later years.

Try the relaxation response

When students are anxious, healthy learning cannot take place. The aim should instead turn to reducing the anxiety as quickly and supportively as possible through a targeted one-to-one intervention or by giving students space to take a break, go for a walk or listen to calming music.

Developed by Dr Herbert Benson in 2000, the ‘relaxation response’ is seen as a quick, effective way to switch off the brain’s ‘fight or flight response’ by engaging the parasympathetic nervous system and returning the learner to a calm state.

“When students are anxious, healthy learning cannot take place”

Encouage students to regulate their emotions when they begin to feel anxious by focusing on their breathing, surrounding sounds or the repetition of a well-chosen word, for instance ‘calm’ or ‘joy’.

Trending

As the student repeats their chosen word, in time with their breathing (if possible), they’ll be able to clear their mind and return to thinking effectively by consciously drawing on this technique.

Showcase the relevance of maths

Bringing the creativity and maths in real life elements of the subject to the fore is helpful in reducing students’ maths anxiety.

That way, lessons become relevant and engaging, conjuring a sense of exploration and curiosity rather than just ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ answers.

As a class, try calculating the probabilities of one reality show contestant winning out over the others. Calculate star salaries, analyse follower counts, predict audience growth trends over time.

Mathematicians regularly work in groups to explore concepts and challenges. Encouraging more teamwork in classrooms can generate creative thinking and engagement with the subject as it promotes vital 21st-century skills, including collaborative problem-solving, as well as mathematical discussion.

To make this a reality, consider the following questions as you plan lessons:

- Would students benefit from more thinking time to feel confident in their answers?

- Is there an opportunity to build in collaboration?

- How could students be grouped to best enable rich discussion?

- Have I included real-life examples that are relevant to my class?

Partner with others to celebrate diversity

Partner with external organisations and maths leaders that promote engagement within STEM, like the Association for Black and Minority Ethnic Engineers or Stemettes.

Celebrate the diversity of people who love and use maths, focusing on individuals who are excelling and breaking down maths barriers, or who paved the way in years gone by.

Invite your learners to see that mathematics is not only open to people ‘like them,’ but could actually help them thrive in later life.

See maths as a diverse subject

Some learners may struggle with trigonometry, but have a real aptitude for algebra, geometry or computing and greatly enjoy studying them.

In the same way that we don’t tend to ‘give up on English’ after reading a style of writing we don’t like, we must encourage students to think of maths as a subject that’s constantly in flux, ever-expanding and endlessly surprising.

Playful tasks to boost pupils’ maths confidence

Use these simple, playful tasks from Mike Askew to help children feel less anxious about offering up answers in maths lessons…

What’s my rule?

Choose a mental calculation strategy that you think is within the current level of competency of the class and that could usefully be practised. For example:

- Adding ten

- Doubling

- Rounding up the nearest multiple of ten

Tell the class that you’re thinking of a secret rule to apply to numbers, but that you’re not going to tell them what it is. They have to figure it out by giving you numbers and seeing which result you give them, based on applying your secret rule.

Go round the class asking for numbers, recording the pairs of numbers as a table on the board. For example, if your secret rule is ‘add five’, you might record:

In / Out

3 / 8

7 / 12

57 / 62

Explain that if anyone thinks they know what the rule is, they should indicate this by putting a thumb against their chest.

As well as getting children to offer you further numbers to act on, select pupils with their thumbs up and give them a number to which they have to apply what they think the rule is. If they are correct, add the pair of numbers to the table.

Once many children have thumbs up, invite them to offer numbers to apply the rule to that they think will help everyone figure it out.

Eventually, ask pupils to turn to a neighbour and agree on what they think the rule is. Can they explain what helped them figure it out?

This can be made more challenging by having a simple two-step rule, for example:

- Double and add one

- Add one and double

- Multiply by ten and add two

Above the line

Choose a way of sorting numbers that children should be familiar with. For example:

- Greater than 50 but less than 100

- Even or odd

- Multiples of five

As for ‘What’s my rule?’, explain that you have secretly chosen a rule for sorting numbers. Draw a horizontal line on the board. Children give you numbers and if they fit your rule, write it above the line. If it doesn’t, write it below the line.

Take suggestions from children in turn, recording the numbers above or below the line as appropriate.

Again, once anyone thinks they know what the rule is, they should indicate this with a ‘silent’ thumb. When you choose ‘thumbs up’ children, tell them that you want them to give you a number and they must predict whether it will go above or below the line.

Again, as this progresses, invite those who appear to know what they rule is to offer numbers that they think will help anyone still not sure of the rule.

One of the things that often happens when I first play this in class is that, as it progresses, children begin to assume that they have to provide numbers that are ‘correct’, in the sense of going above the line.

It helps to talk about how you can’t be ‘wrong’ in offering a number, and how, often, the numbers below the line can be more helpful in checking what the rule is than those above it.

Again, this can be made more challenging by having two criteria for sorting, or a slightly less obvious criterion, for example:

- One more than a multiple of three

- A multiple of five between 60 and 120

- A whole number (it can take quite a while before someone suggests a fraction)

Can you make…?

Children each need a set of 0-9 digit cards. Ask pupils to mix up their cards and randomly set aside five of them.

Set various challenges for making numbers that the children have to use their remaining cards to show solutions to, for example:

- A two-digit number between 50 and 100

- An even number less than 75

- A three-digit number with a fewer number of tens than number of ones

- A multiple of three greater than 36

- A number that is a multiple of five and has ten as a factor

Develop it further

This can be developed into having to make a pair of numbers (still from the five remaining cards) that satisfy certain conditions. For example:

- Make two two-digit numbers that when added together have an even answer

- Make two two-digit numbers that sum to more than 70

- Make two two-digit numbers that have a difference of more than 20

- Make a two-digit number and a one-digit number that when multiplied together have a product less than 50

- Make a two-digit number and a one-digit number that when you divide the larger number by the smaller, there will be no remainder

These challenges are helpful for bringing children’s attention to the power of reasoning over working out actual answers.

For example, in looking for two two-digit numbers with a difference of more than 20, children might reason that if they make a number in the 50s, then 20 less than that number is going to be in the 30s, so any number in the 20s or below will satisfy the condition.

Mike Askew is adjunct professor of education at Monash University, Melbourne and a freelance primary maths consultant. Visit his website at mikeaskew.net and follow him on X at @mikeaskew26.

Thank you to the following people for their help with this article:

Brent Hughes is a teacher educator at Matific. Marie Thompson is a qualified teacher and now works in the post-19 education sector. Watch Marie’s maths anxiety webinar via video CPD website The National College.

Alexandra Riley is senior strategy manager for secondary maths at Pearson. Read Pearson’s Guide to Tackling Maths Anxiety. Nicola Woodford-Smith is a maths subject partner for Pearson, having taught maths for 13 years at both GCSE and A Level.