Practical skills – Let’s end the sidelining of practical knowledge in schools

After decades of neglect, educators and policymakers are belatedly realising just how important – and costly – the teaching of practical knowledge actually is…

When I trained to be a physics teacher in the mid-1990s I never imagined that 25 years later I’d be working from a makeshift classroom at the back of a hair salon, surrounded by sinks and blow-dryers.

I’ve spent the last couple of years out of schools, mainly teaching hairdressing apprentices basic numeracy and literacy for Functional Skills qualifications in a work-based learning setting.

It’s been a privilege, allowing me to meet many fantastic people who, despite struggling with the basics of primary-level learning, possess the acumen and skills needed to run very successful, fast-paced businesses.

And yet, I so often hear these people describe themselves as ‘failures’ at school. When I’ve asked my apprentices what they mean by this, they invariably give an answer along the lines of, “I wasn’t academic. So I’d sometimes get into trouble. I was just good with my hands. So I didn’t leave with many qualifications.”

Practical knowledge versus conceptual knowledge

These conversations have made a deep impression on me, given my classroom background, and I soon came to realise that such narratives contained several PhDs’ worth of research questions.

How can someone spend over a decade in formal education, yet leave barely able to read or multiply? What do we actually mean by the word ‘academic’? Are teachers and students even talking about the same thing?

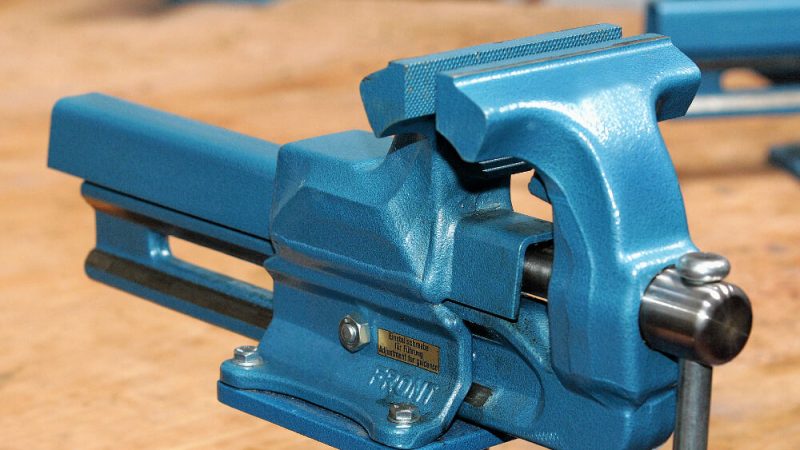

Above all, to what extent is practical knowledge – that ‘being good with one’s hands’ – different from abstract, conceptual and propositional knowledge? Is there enough room for this approach to making sense of the world within the field of academic knowledge?

When I was at school, an O Level in woodwork was a byword for low achievement or lack of intelligence; as if anybody could get one.

Several generations and a global pandemic later, however, the wider culture is now waking up to the importance of practical knowledge, and belatedly realising that the smooth running of society rests at least as much on tradespeople as it does on office drones typing on computers.

Practical knowledge in the curriculum

But there’s a problem, in that it’s also become apparent that practical knowledge isn’t as cheap and easy to acquire as the old jokes led us to believe.

Moreover, whenever the issue is raised, the discussion tends to focus to post-16 further education. I believe the issue warrants attention at an earlier stage, in secondary schools.

Our curriculum has gradually squeezed out room for acquiring the kind of knowledge Michelangelo alluded to when he said, “I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free”.

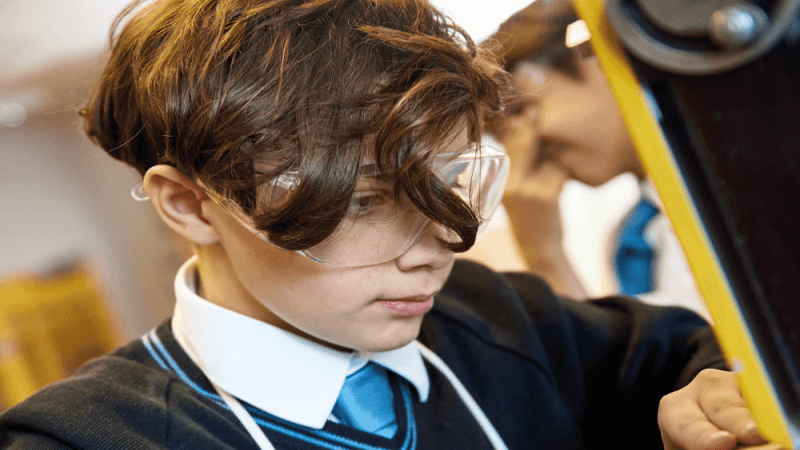

If children aren’t given opportunities to explore the nature of craft in a systematic, disciplined fashion early in secondary education, why should they suddenly be expected to make wise choices about vocational training and education at 16?

The social commentator David Goodhart addresses some of these themes in his latest book Head, Hand, Heart: the struggle for dignity and status in the 21st century, which we recently discussed at the Academy of Ideas Education Forum (view a film of the discussion here).

Goodhart isn’t an educationalist, and his book is principally a work of sociology. However, it concerns the intersection between different kinds of knowledge and their place in schools and beyond.

It examines the instrumental purposes to which education – particularly higher education is put in our society and the ‘credentialing’ role of exams.

It questions the function of education in creating democratic citizens, and the part played by education in creating a new type of elite – all of which I believe are important issues for those working in schools.

The importance of manual skills

Goodhart’s central claim is that “smart people have become too powerful”. By this, he means that the abilities needed to pass exams and handle information efficiently has become “the gold standard of human esteem”.

Those possessing such aptitudes have subsequently formed a new class – a ‘mass elite’, as he calls it – which is shaping society in its own interests.

For those employed in manual work or the caring professions, it’s another matter entirely. “It is becoming harder to feel satisfaction and self-respect living an ordinary, decent life, especially in the bottom part of the income spectrum,” writes Goodhart.

In the process, secondary education has become largely predicated on getting as many people into university as possible, thus placing a disproportionate focus on the ‘head’ (the cognitive-analytical), to the detriment of ‘hand’ (the practical and somatic) and ‘heart’ (the social).

Those taking non-graduate paths are getting increasingly left behind.

In this way, says Goodhart, one’s educational achievement has become a way of signalling membership of this mass elite, rather than setting a person up for different walks of life.

He warns that we are now reaching a period of ‘peak head’, whereby increasing automation driven by artificial intelligence, combined with an oversupply of the analytically trained, will most likely lead to a collapse in the status of these ‘head workers’.

Curriculum reform

One could read the ‘progressive’ child-centred, discovery-based learning educational theory of the last 40 years as a pro-hand, pro-heart and anti-head, movement, while the school reforms of the 2010 instigated by Michael Gove might be seen as a pro-head, anti-hand reaction.

Goodhart, however, observes the situation as being more complex than this. Progressive education has done little to improve the prospects of those inclined towards the trades, while the caring professions – notably nursing – have seen an increased demand for academic qualification, all of which has taken place against a backdrop of ever swelling numbers of undergraduates.

So what to do? How might we create a more rounded, liberal education that restores the dignity of hand and heart, according equal status to each? This is perhaps where Goodhart’s book is at its weakest, but one interesting proposal he makes is to require for every child to learn at least one practical skill during their secondary education.

He also touches on the difficulties that arise when post-16 vocational education tries to make up for the numeracy and literacy deficits that too often occur earlier on in pupils’ education.

One solution currently being discussed among some educationalists, though Goodhart doesn’t mention it, is for schools to approach the development of numeracy and literacy differently from the rest of the curriculum, by adopting a ‘driving test’ proficiency model of assessment – a system whereby pupils may take tests as often as necessary, which they must pass eventually.

Post-secondary paths for students

Whatever the way forward, there’s much in Goodhart’s diagnosis of our contemporary problems that rings true. Secondary education has somewhat lost its intrinsic purpose, and is too often used as a proxy for other aims.

The urge to routinely send young people to university is neither necessary nor to be desired, either individually or socially. The role this plays in distorting the whole system is worthy of scrutiny.

Moreover, practical and non-abstract knowledge continues to be sidelined in schools, with subjects such as art, music and dance all facing difficulties. Even the practical aspects of science – a core subject, no less – are in decline.

These are issues that should force all sides in the education debate to ask themselves some difficult questions.

Learning as a balanced combination of head, hand and heart is one way of framing the present situation, but the key point is that teachers should continue to think deeply about the wider purpose of what they do, hour-by-hour and day-by-day – and what the wider implications are likely to be for society as a whole.

Gareth Sturdy is a secondary science advisor and teaches mathematics and English to apprentices; he also co-organises the Academy of Ideas Education Forum and can be followed at @stickyphysics.