GCSE history – Help your students think beyond ‘good’ and ‘evil’

Elena Stevens takes issue with the tendency among students to lionise or demonise historical figures, and how this can lead to an oversimplified view of the past…

Perhaps inspired by their experiences of social media, young people seem obsessed with binary notions of ‘good’ and ‘bad’.

Many students appear to be convinced that historical figures can only ever be one or the other, and enthusiastically devise hierarchies of ‘good/ evil’, ‘hero/anti-hero’ and ‘success/failure’ – often on the basis of some gruesome atrocity or outstanding accomplishment.

Essentially, students want to know whether the individuals they’re studying ought to be admired or vilified. Was General Haig the ‘butcher’ or ‘hero’ of the Somme? Should Churchill’s achievements as Prime Minister be celebrated, or his murky imperialism condemned? Was Boudicca a great warrior queen, or the brains behind a brutal ethnic cleansing?

Binary lenses

This dichotomising approach is problematic for a number of reasons. Not only does it flatten much of the complexity that makes history interesting and relevant to us today, but it speaks to a wider tendency amongst young people to view the world through over- simplified, binary lenses.

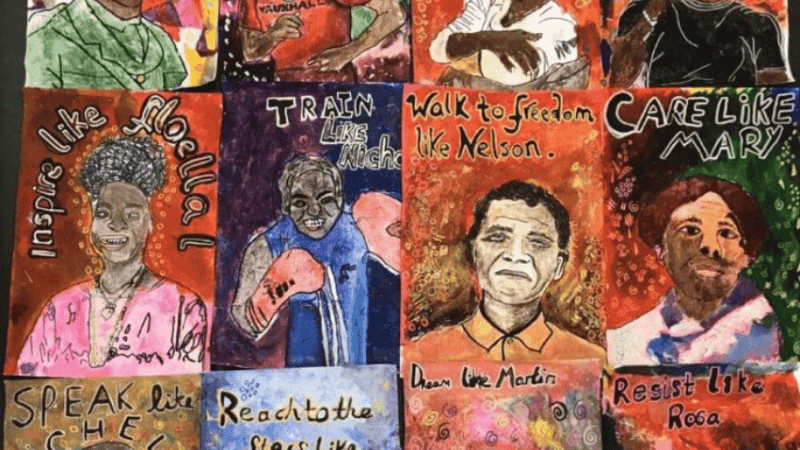

One of the best ways of challenging these ideas is to offer a more holistic view of people from the past, while also encouraging students to explore the experiences of individuals – both well- known and ideally also lesser-known – who they’ve been aware of throughout their lives, rather than simply focusing on the moments for which they are best known.

Take ‘Nelson’s mistress’, for example. Emma Hamilton was one of the 18th century’s most famous women, but a quick Google search gives the impression that Hamilton is a significant figure only by virtue of her affair with ‘naval hero’ Lord Nelson.

In actual fact, Hamilton was an actress, dancer, artist’s model and the originator of the ‘attitudes’ – a performance style in which she imitated ancient Greek statues for her classically-obsessed audiences.

Her story might not fit traditional narratives of historical significance, but I believe it’s important to give students the chance to encounter and consider different aspects of social and cultural history, particularly when exam specifications are so heavily weighted towards political and military history.

More nuance

I would encourage students to chart the ups and downs of Hamilton’s life, in order to help them understand in a more nuanced way someone who was a complex individual, as well as 18th century life and culture more generally.

Students could study the letters a young Emma Hamilton sent to Charles Greville, which reveal an endearing infatuation with the older artist. They might then read excerpts from the diaries of William Hamilton (her antiquarian husband) and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, both of whom waxed lyrical about her ‘attitude’ performances.

Finally, students might consider the rather condescending approach taken by contemporary media, with caricaturists of the time portraying Hamilton as idle, overweight and undeserving of her advanced social position.

Charting the highs and lows of Hamilton’s biography lets students view the broader sweep of this individual’s life, while noting the various influences that acted upon it. Posing questions like ‘At what points in Hamilton’s life did she achieve greatest success?’; ‘Why were things so bad for Hamilton at x point?’ and perhaps even ‘When do you feel most sympathy with Hamilton?’ can help students better appreciate that ordinary lives are characterised by constant fluctuation.

By taking a step back, we can see that no one individual can be deemed simply ‘good/ bad’ or a ‘success/failure’.

The mother of Caribbean carnival

Of course, there are numerous other case studies for which a similar approach might be appropriate; the key is to ensure that there’s sufficient source material around which to build a full historical enquiry.

Trending

Claudia Jones, the ‘mother of Caribbean carnival’, is one such individual who fits the bill. Jones endured significant discrimination as a Trinidadian-born immigrant, before she channelled her frustrations into the campaign for Black rights and representation and eventually established the Notting Hill Carnival in 1959. Her story can be helpful for illustrating the stop-start nature of Black British activism during the mid-20th century.

Similarly, the life of political dissident Aruna Asaf Ali exemplifies the complicated trajectory of the Indian independence movement. French diplomat and cross-dresser, the Chevalier d’Éon, helps us build a more rounded picture of life in pre-revolutionary France. Like those of Hamilton and Jones, these life stories are complex and fundamentally unpredictable, fitting neither the narrative of triumph or disaster.

The limits of humanising

When taking this approach, however, we must avoid building such enquiries around individuals for whom there are no redeeming features. It’s useful to identify the ups and downs in the personal histories of people like Hamilton and Jones, because doing so affords valuable opportunities to emphasise the fleeting nature of perceived successes and failures.

Conversely, it wouldn’t be appropriate to identify evidence of ‘success’ or ‘good’ in the lives of, say, Hitler or Stalin – nor indeed to encourage students to find justification in wider narratives for such individuals’ abhorrent behaviour.

Every year, my students come across photographs of a dashing young Stalin while reading about his penchant for Westerns, and find out that Hitler’s beloved mother died when he was just 18. From these discoveries, some begin to build a case for Stalin having been less than purely evil, or Hitler deserving sympathyfor ‘the things he went through’. This is not the intended outcome of my approach!

I remain confident, though, that by taking a more holistic approach to the study of individuals in the past, we can go some way towards ‘humanising’ the history that we deliver to our students. Exposing young people to these kinds of stories will ultimately encourage them to develop a more complex, nuanced understanding of history.

It will also (hopefully!) serve to challenge some of the problematic dichotomies to which young people cling when it comes to the analysis of human character.

History, humanised

Three lesson activities that can lend a personal dimension to your studies of notable historical individuals…

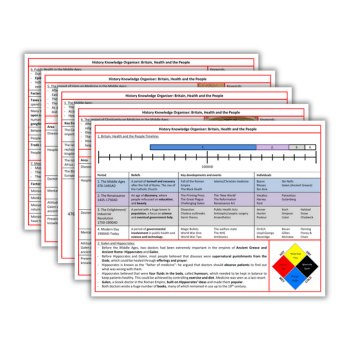

1 The living graph

Students plot episodes from an individual’s life onto a graph with a ‘y’ axis ranging from ‘happy/successful’ at the top to ‘unhappy/ unsuccessful’ at the bottom, and a chronological ‘x’ axis increasing in years from left to right. This allows students to chart the person’s highs and lows over time and analyse the impact of wider contemporary events on their life.

2. Decision-maker

Students consider how they themselves might have responded to the choices faced by those in the past. Present students with a series of dilemmas faced by historical figures and offer various options for dealing with them. How closely do the students’ decisions match those of the individual(s) in question? What factors would they have had to take into account when making their decisions, and how did things change as a result?

3. Counterfactual history

Students consider how the experiences of those in the past might have differed if they had taken a different course of action. Speculate about alternative ‘endings’, reflecting on the possible long-term impact of these imagined realities.

Elena Stevens (@elena_stevens) is a secondary school teacher and history lead; her new book, 40 Ways to Diversify the History Curriculum: A practical handbook is available now (Crown House Publishing, £16.99)