Teaching to the test – Are we even teaching at all?

Teaching to the test alone will do your students few favours, warns John Lawson – but some drilling can go a long way…

- by John Lawson

- Former teacher, governor, author & owner of tutoring service Visit website

Should we ever ‘teach to the test’? Absolutely! Should we be solely teaching to the test? Absolutely not.

I’d never have passed my GCSEs without combining studying outside the box with specific prepping for tests. My seminary professors, on the other hand, were rock-solid Romantics who never knowingly tailored lessons to the dictates of the day’s exam questions – which created needless anxiety and stress for their students.

Only by seeking out and studying past papers myself did I learn how to connect parables of the Kingdom (from Matthew’s Gospel only) to Catholic social teachings or specific papal encyclicals. Yes, I wanted to be ‘saved’ – but I also wanted a degree.

Demystifying the papers

Exam skills will often determine students’ final grades, and therefore merit serious scrutiny. There’s a telling observation in David Lodge’s 1975 novel Changing Places. The character of Professor Swallow is tinkering with and polishing exams that “Mix easy questions on obscure authors with obscure questions on easy authors.”

Now, as it was then, too many examiners delight in fashioning cryptic clues for their exam papers, rather than clear, unambiguous questions.

So long as exam questions remain rendered in awkward prose and are closed, rather than approachable and open, it’s up to teachers to assist their students in demystifying these all-important exam papers that will so profoundly shape their futures.

If teaching to the test advocates consistently help their students to achieve outstanding examination results, then they deserve our respect.

I’ll stop being a ‘teaching to the test’ teacher myself once we regularly award stellar grades to those students who appreciate art for art’s sake, and when principals, parents, and pupils no longer stress so much over results.

Trim the fat

I remember once being assigned an A Level class on church history because my HoD couldn’t settle on how to teach 2,000 years of history over the course of 35 lessons. The answer? Trim the fat! (though yes, this is admittedly more difficult to do with some subjects compared to others.)

Far from being an act of vandalism, this streamlining process is actually the realist’s pathway to sanity and success. When exam boards overload those courses, get creative. I recently went through ten years’ worth of past papers and soon identified eight topics that would invariably appear:

- leadership

- heresies

- the fall of Rome

- The Council of Chalcedon

- St Thomas Aquinas

- the Reformation

- the Renaissance

- Vatican II

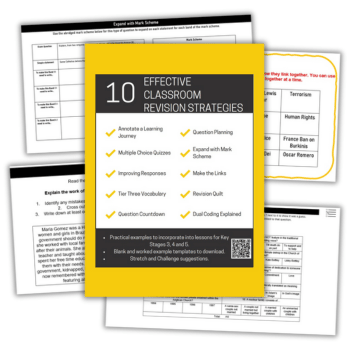

I taught all of these topics comprehensively, and ensured students knew of their centrality to our understanding of historical Christianity – which will be why examiners routinely highlighted them. We didn’t do mock exams, though, since testing isn’t teaching. Instead, I dissected 20 exam questions over the course of four revision lessons, in effect teaching students how to examine the examiners. That’s a vital life skill, and as added bonus, seven of those aforementioned topics came up.

That same year I’d read 40 books on church history within eight months, feeling confident afterwards that I was among the country’s best read and most energised RE teachers.

The students’ enthusiasm for this exercise reassured me that I’d managed to convey an engaging narrative, which subsequently helped them better understand the crucial distinctions between the Jesus of History and the Christ of faith. Throughout the course, I’d focused on when and how the Church had succeeded, and when it had failed to be a spiritual force for good. That was the guiding question that informed everything.

The source and the summit

The greatest failure we can indulge is to let the tail wag the dog, and regard exam certificates as both the source and summit of our students’ lives. Because there’s much, much more to education than that.

A grounding in MFL will enable students to communicate with others whose native culture and tongue are sources of immense pride and identity. Aspiring mathematicians should acquire abiding respect for a universal language that has, and continues to dramatically transform all our lives. Theology teaches us the supreme importance of the language of love.

When we refuse to care for others, we merely make noises that ultimately hurt everyone. A God who engenders fire and brimstone rather than unconditional love is unworthy of our worship. God’s greatest gift to the world was intelligence – and I refuse to leave mine unboxed.

Every subject has a universal eminence that goes far beyond mere grades. If we allow a soulless focus on tests alone to dominate and discourage us from independent thought, then we’re no longer educating.

John Lawson is a former secondary teacher. He now serves as a foundation governor while running a tutoring service. He is author of the book The Successful (Less Stressful) Student (Outskirts Press, £11.95). Find out more at prep4successnow.wordpress.com or follow @johninpompano.