Evidence-Informed Practice in Teaching is Much More than the Latest Educational Fad

Avoid the perils of untested interventions that do more harm than good by embracing research-informed practice, say Dave Harris and Professor John West-Burnham…

“The other side of the social media coin is the ability of some individuals to push their own personal opinion and prejudice”

Evidence-informed practice is the latest trend to hit schools. As with all trends, it is right to be cautious.

However, properly used and understood, it has the potential to make a genuine and positive difference to teachers’ lives, children’s learning and school improvement.

Evidence-informed practice means moving away from one person’s experience or dominant view as the basis for our working policies and procedures, and looking instead for ideas and policies that are based on reliable and trustworthy evidence.

This is almost the same as the changes in medicine over the years – moving from guesswork and supposition to high confidence in both diagnosis and prescription.

Nowadays, no new medicine can be offered to patients unless it passes rigorous testing to ensure that it is safe, effective and, often controversially, financially efficient.

There are a number of reasons why many schools are exploring evidence-based practice as a better way of working.

Firstly, it helps to guide teachers and school leaders when they have to make complex decisions.

Secondly, evidence-based approaches, combined with school-based research, mean that as teachers, we are able to focus our professional learning on actual practice in the classroom with priorities that we ourselves have set.

Thirdly, in these times of economic stringency, evidence-based approaches can help to ensure that we use scarce resources to best effect and in a way that makes the greatest impact on teaching and learning.

Of course, evidence-based working is not limited to education. There has also been a very strong move towards it across the public sector, including in medicine and policing.

Across a range of professions and public services, evidence of what works and what doesn’t via formal trial and error has become a foundation of professional practice.

This helps to avoid us falling into the trap of championing untested interventions that do more harm than good and are wasteful of public and private resources.

Evidence-based practice can take many forms.

For many schools, the most appropriate starting point is to explore the potential of teachers taking significant responsibility for their professional learning by exploring ways of encouraging collaborative research into actual classroom practice.

This approach is often referred to as ‘action research’ or ‘action learning’. The best known version of this is lesson study, where a group of teachers work together to identify an area for development in their pupils’ learning. If you are interested in promoting evidence-based research approaches in your school, a good first step is investigating what types of evidence are currently used in your school.

Trending

For example, have you taken part in research carried out by academics in universities or research organisations? Have teachers at your school carried out research for academic purposes, such as a master’s degree? Do staff members do research into their own practice as a professional development activity?

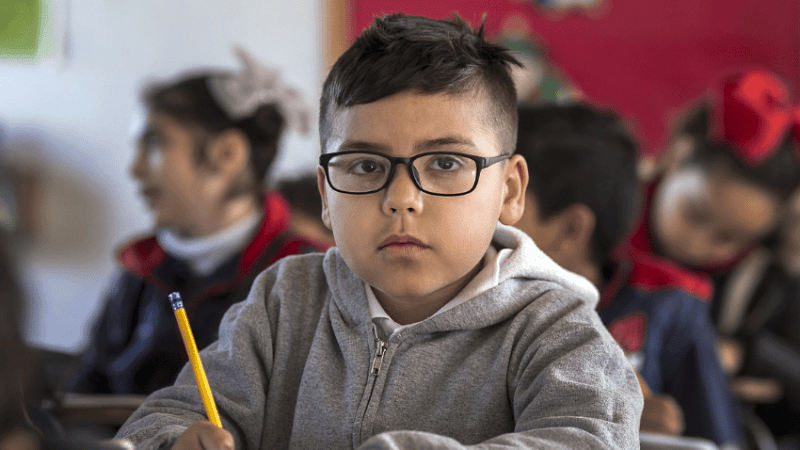

In these times of high stakes accountability, where we all face sustained pressure to secure improvement, reduce resources and ensure our most disadvantaged and vulnerable young people make progress, the case for better levels of sophistication in our decision-making seems unquestionable.

However, there are also real issues to overcome. Do staff have the knowledge and skills required to conduct quality research?

Do you have the appropriate resources, and most importantly, the time to develop a culture of enquiry and analysis in your school.

Here are some examples of areas you could look to improve in your setting with the help of evidence-based practice:

- The accuracy of special needs and specific learning needs diagnoses

- Teaching and learning strategies

- School policies and initiatives

- The suitability of new resources in terms of cost-benefit

Another increasingly popular vehicle for school-based research and practice is social media. This is rapidly becoming a very powerful tool in disseminating ideas and innovative practices.

However, the other side of the social media coin is the ability of some individuals to push their own personal opinion and prejudice, to the detriment of an open approach to differing views. If you want to raise the quality of your school’s approach to research-informed practice, here are some practical ideas to start with:

- Replace traditional course-based CPD with dedicated time and resources to support research (eg lesson study)

- Designate a member of staff as research coordinator and ensure they have access to research publications and have time to manage bids for funding

- Develop links with the staff and library facilities at your local university. Can you secure accreditation of your school-based activities?

- Ensure middle leaders are up-to-date with their subject knowledge and pedagogic research

- Set up a book club for senior leaders where you agree to read and discuss one key text every term

Wherever your school, whoever your staff, it would be crass to assume that you have all the answers, but equally wrong to assume that someone else does.

Put simply, the process of looking at your own practice in detail will help you to begin to make the changes you need in your school.

Be brave and dip a toe in the water of research.

Professor John West-Burnham is director of three academy trusts and an education leadership consultant. Dave Harris worked for over 20 years in school leadership. Together they have authored Leadership Dialogues II: Leadership in Times of Change (£24.99, Crown House Publishing).