GCSE English Literature – Best 2025 revision aids for your students

Help students prepare for this half of the English exam with this collection of useful tips and tools…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Navigating the vast sea of GCSE English Literature resources can be daunting. Here we’ve curated the best revision aids to empower your students and enhance their understanding and performance. Here’s a useful video for starters…

GCSE English Literature revision resources

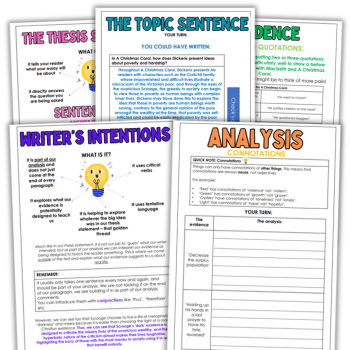

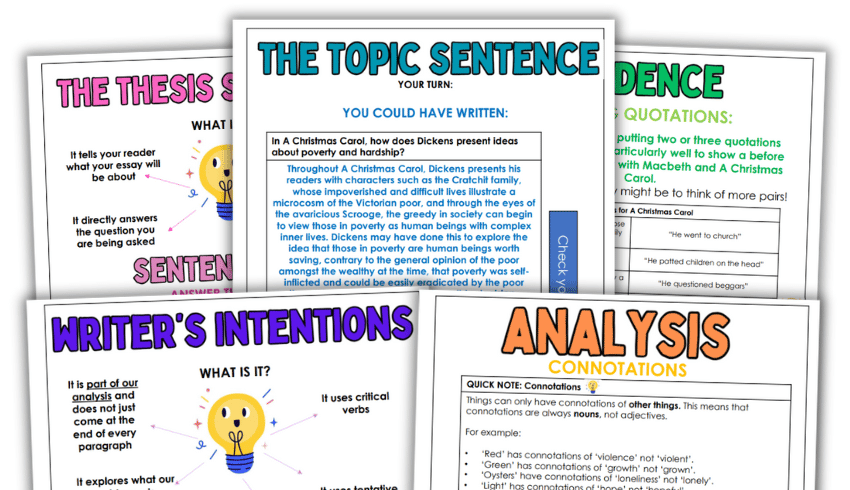

Complete essay writing guide

This free essay writing booklet is a step-by-step guide for GCSE students. It focuses on building strong arguments, analysing texts effectively and using evidence to support ideas.

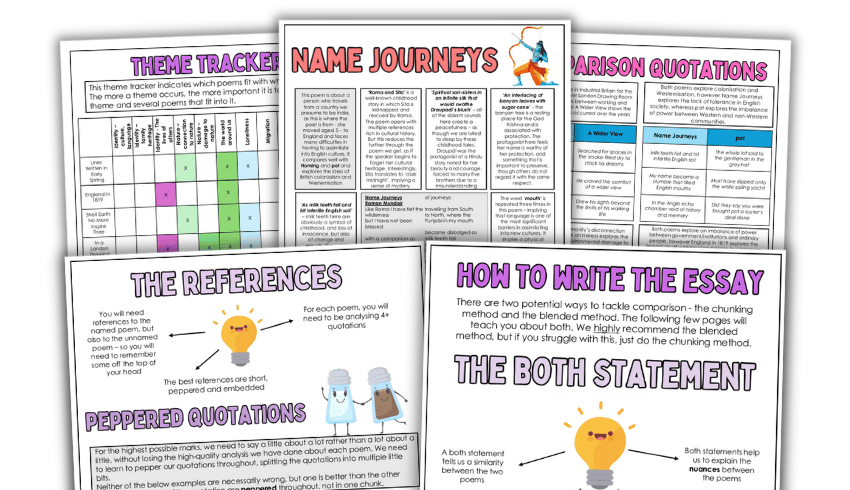

Worlds and Lives poetry revision guide

This free teacher-made Worlds and Lives poetry anthology ultimate revision guide provides everything students need for effective revision.

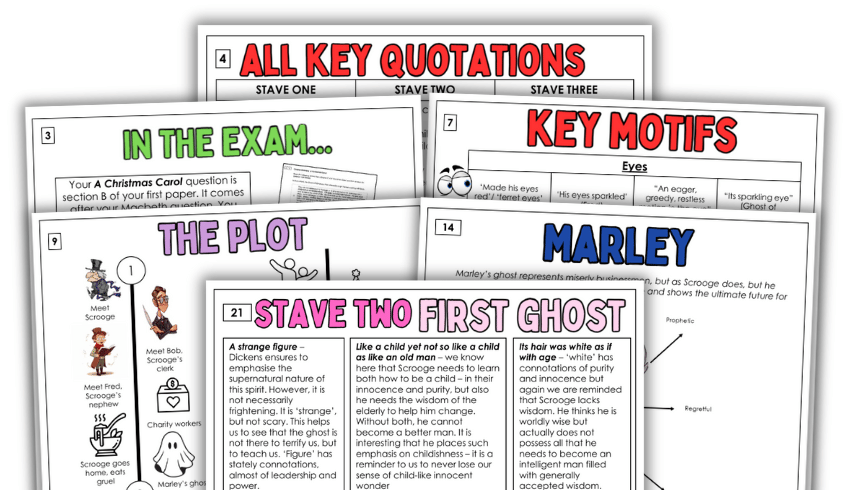

A Christmas Carol revision pack

This free, teacher-made A Christmas Carol revision guide is a detailed and practical resource designed to support you in preparing students for their GCSE English Literature exam.

It provides an in-depth analysis of Charles Dickens’ novella, offering a structured approach to revision and study.

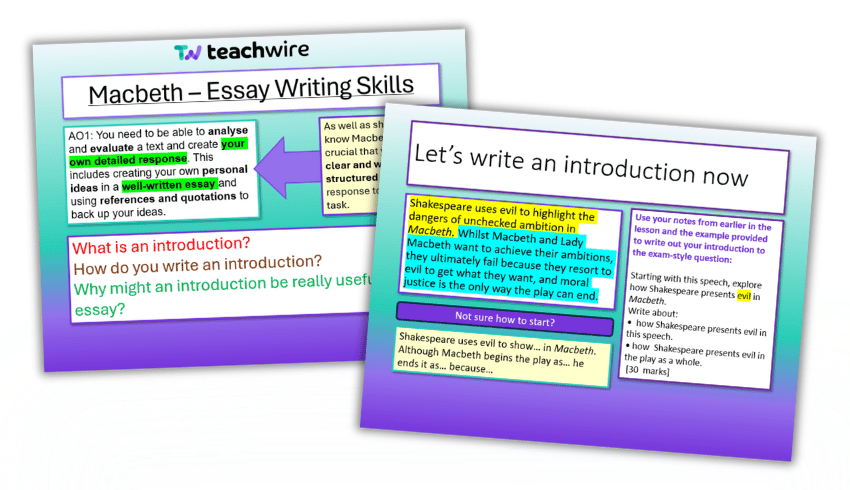

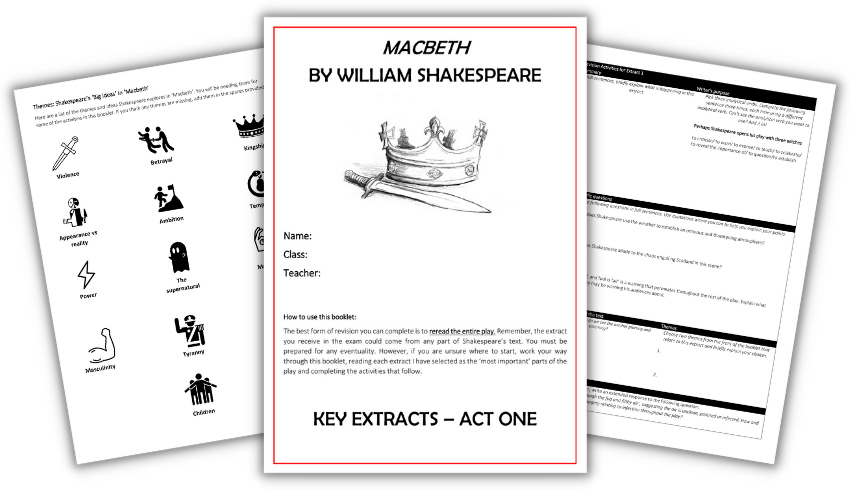

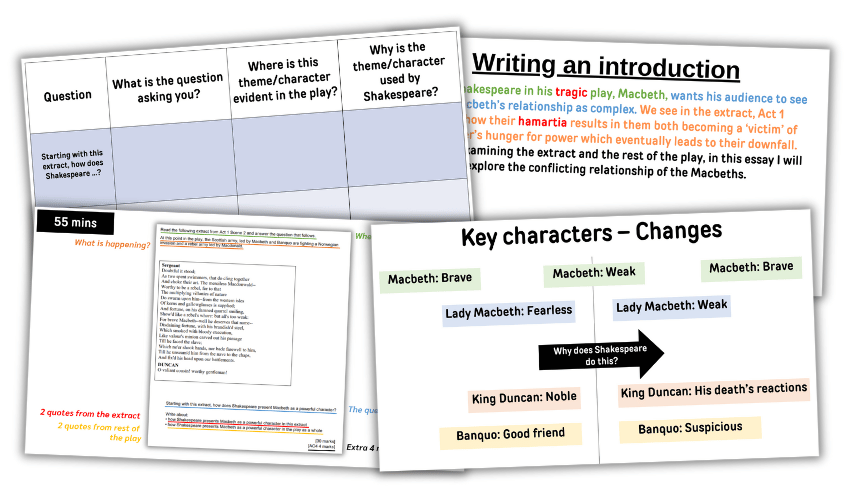

Macbeth essay writing resource

This free, detailed Macbeth essay two-lesson resource pack contains two comprehensive PowerPoints which will support KS4 students in constructing coherent and clear essay structures for an exam-style question.

We also have a free Macbeth revision download which includes 20 lessons’ worth of material, including Powerpoints and supporting resources for each session.

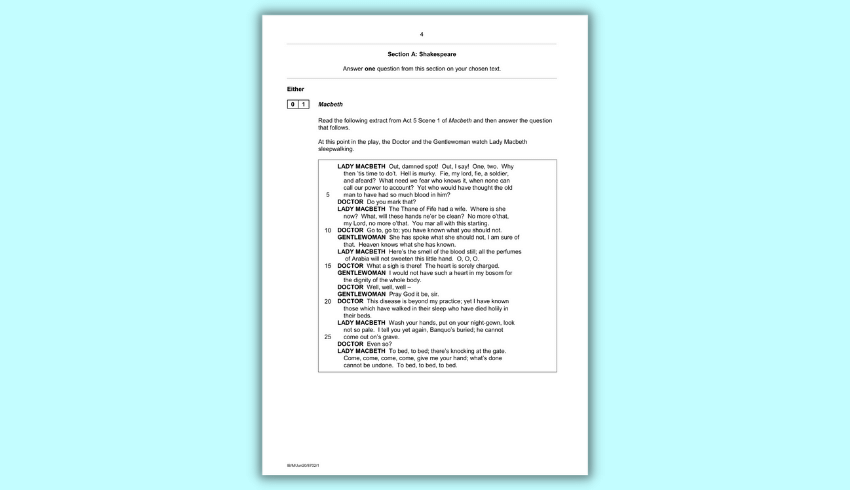

Macbeth/Christmas Carol walkthrough

If you’re preparing students to sit their GCSE English Literature exam, use this free AQA English Literature Paper 1 PowerPoint/PDF to walk through a past paper with them. It focuses on Macbeth and A Christmas Carol.

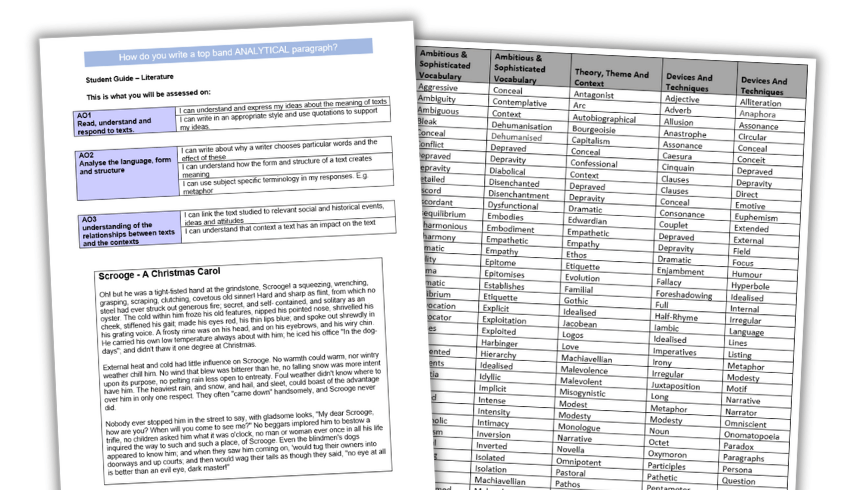

GCSE English Literature quote analysis guide

This free resource is a guide for GCSE English students on how to effectively analyse passages and quotes from texts.

It uses a passage from A Christmas Carol and includes a number of activities to try in class or at home. There is also a vocabulary list of words to use in analysis.

Analysing song lyrics as unseen poetry

This free unseen poetry GCSE lesson plan involves studying Firework by Katy Perry to support the development of key GCSE skills.

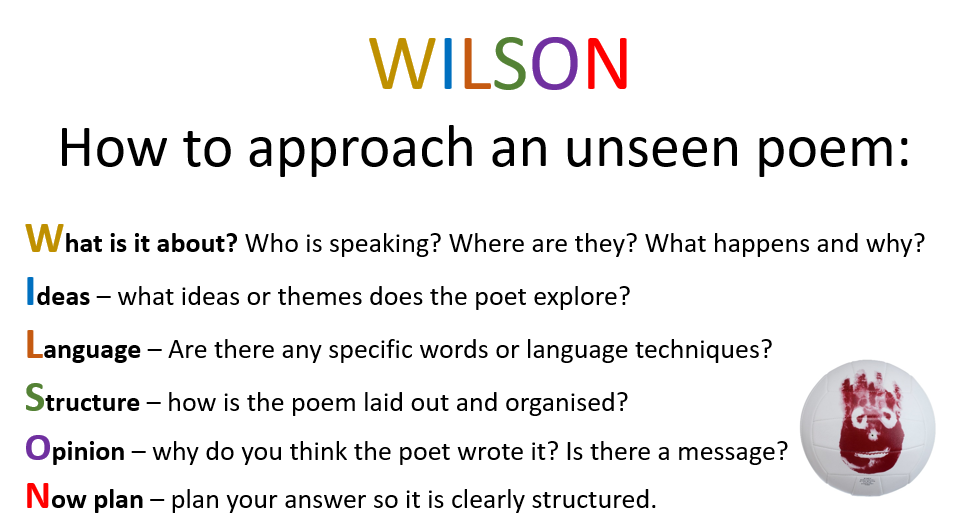

Unseen poetry scheme of work

This free scheme of work from English teacher Toby Grimmett teaches students how to analyse the language, structure and form of unseen poems using differentiated resources and extension tasks.

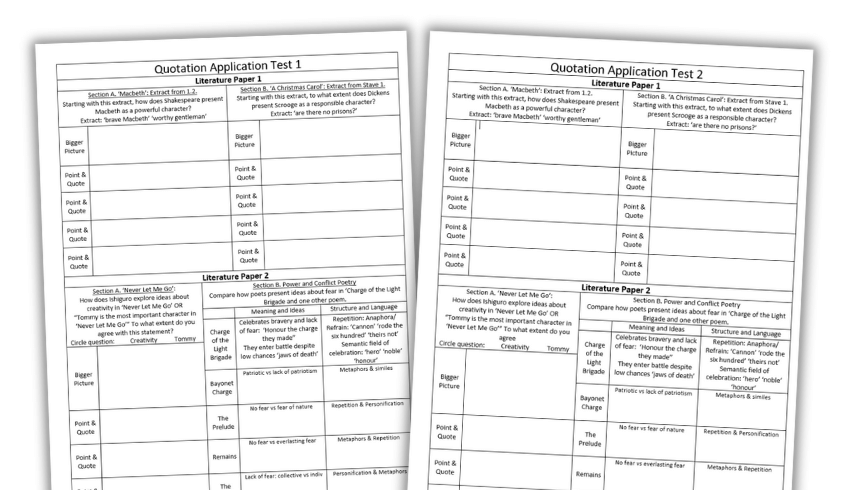

AQA quotation planning tests

This free 15-20 minute activity from English teacher Laura Holder asks students to plan an answer to section A and B of both GCSE English Literature papers.

Unseen poetry mock GCSE lesson plan

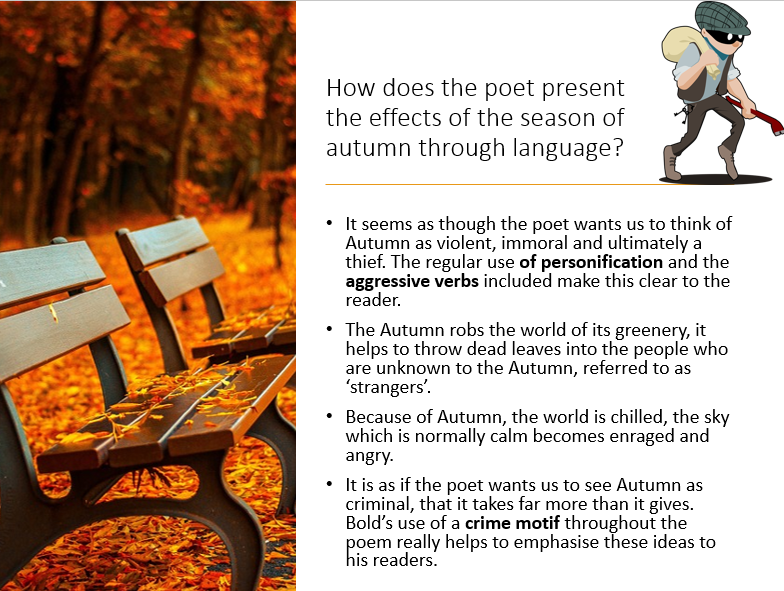

This free, fully differentiated lesson looks at Paper 2-style AQA English Literature unseen poetry questions for ‘Autumn’ by Alan Bold and ‘Today’ by Billy Collins. It’s easily adaptable for other exam questions and exam boards.

GCSE set text resources

We’ve rounded up resources for a number of popular KS4 novels. Check them out at the links below:

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

- Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

- Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

- Animal Farm by George Orwell

- A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

Revision videos

Mr Bruff’s YouTube account has a nice selection of revision videos, covering topics such as avoiding common mistakes, selecting and memorising quotations, looking for patterns and full marks example answers.

Quizlet flashcards

On Quizlet you can look at free expert-verifiied flashcards to help students revise for GCSE English Literature. Simple choose your exam board, text and area of revision.

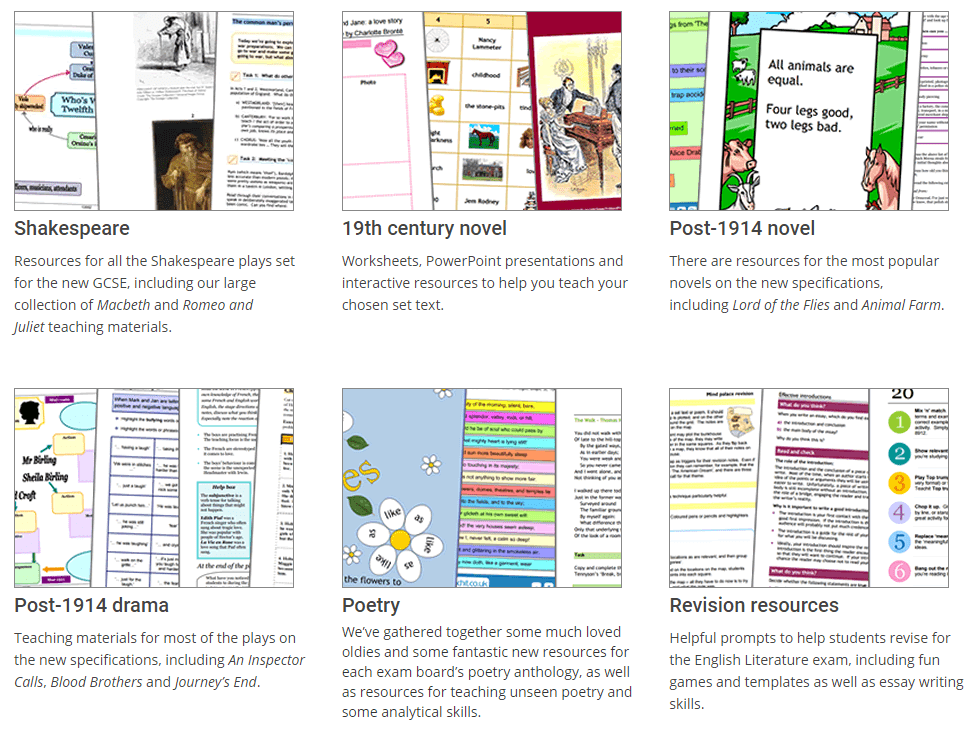

GCSE literature overview

If there’s anything we’ve not covered, there’s plenty more at Teachit English where you’ll find sections on Shakespeare, 19th-century novels, post-1914 novels, post-1914 drama, poetry and other revision resources.

English literature past papers

Looking at previous papers is an essential part of preparing for exams, so whether you want to look over some in class or direct students towards them to look at at home, you’ll find AQA, Edexcel, WJEC, OCR, Eduqas, Pearson and CIE tests at Revision World.

Nic Worgan’s GCSE revision

Nic Worgan has a whole host great literature-based videos on her YouTube channel that are well worth checking out. There’s the above video on unseen poetry, plus key quote quizzes for GCSE texts like Jekyll and Hyde, An Inspector Calls and various Shakespeare plays.

How to banish GCSE English Literature exam fears

Eradicate those pre-exam fears plaguing your students with this advice from English teacher Jennifer Hampton…

If a certain type of exam response has become a threatening behemoth, break it down. Learn a set of quotations in class around a specific theme or character, perhaps with the aid of mini whiteboards, pair talk, timed conditions and/or buckets of praise.

A set of short quotations firmly lodged in students’ heads equals a win, and with every win we feel more successful, more empowered and less afraid.

We practise a similar approach when it comes to verbs that explain effect (‘emphasises’, ‘highlights’, ‘reinforces’, ‘creates’ etc.) and phrases relating to social and historical context.

We can do it with adjectives that describe character, or indeed many aspects of the complex responses our students will be required to give in the exam.

Active revision modelling

Beware those pretty notebooks and flashcards that haven’t yet become grubby through continual handling and flipping.

It’s worth reflecting on how many of our students see their studies and exam preparation as a solitary, inactive and ultimately passive activity.

I myself now know that the hours I spent studying for both GCSE and A Level exams could have been utilised so much more productively had I known just how ineffective my 1am note copying sessions really were.

As Pie Corbett – the brilliant teacher, trainer and poet behind Talk For Writing – says,‘If you can’t say it, you can’t write it’. That’s certainly something I need to consider more in my own practice.

Emphasise to your students that their beautifully neat notes are next to useless unless they’re also kept securely in their heads.

Immersion and joy

All of us will have different opinions on the texts we teach, the selections we’ve made and the factors governing those choices.

We need to recognise that at some point, we have to acknowledge the value and worth offered by even our most loathed set texts.

Select the best chapter, best act or best online poetry reading of the texts in question, and then just read and/or listen to them – potentially for the duration of a whole lesson.

Invite your students to identify their own favourite lines, or pick out a work’s most humorous moments or haunting sentences.

Try to recapture that moment when your fresh-faced Y10 students were first presented with a text’s then-new words, long before assessments, mocks and feedback began to eat away at its appeal.

Relax, immerse and do your best to help everyone enjoy those well-written texts as if PETER paragraphs had never been invented.

Pair writing

How can we turn the demands of assessment objectives on responses inside out? One way is to outline what these actually are, and ask students to co-write a single response. Two brains, one paragraph/essay.

By doing this, we’re not only facilitating the exposure of different writing styles and different interpretations, but also different sets of notes.

Needless to say, this is an activity in which students will need be matched carefully, and for which ground rules will need to be laid down.

Both students must physically contribute to the actual writing. Both sets of notes/resources will need to be accessible, and both should actually understand what it is they’re writing.

Once the activity is complete, invite your students to look back over their responses and take the best phrases and ideas from both.

Yes, it can take practice and monitoring to get this right, but even the inevitable minor disagreements between partners will help to develop their knowledge and expression.

Tentative language

‘Could’, ‘maybe’, ‘possibly’, ‘perhaps’; such tentative language (often heavily demanded at undergraduate and Master’s level) can give nervous students a renewed sense of confidence, especially when faced with previously unseen texts.

Model sentences that contain these words. Encourage their use in verbal responses during class discussion.

Explain how they’re frequently employed in academic writing, and emphasise how they can raise the intellectual bar of our writing while also, fabulously, giving us an insurance policy if we’re perhaps a little bit off.

Comprehension and the basics

As evidence mounts that students’ comprehension skills often aren’t as developed as we think, it’s worth checking to see if they really get it – especially when it comes to unseen poetry.

How often have you watched students spot a simile prior to reading the whole poem? Most of us will also have seen the detrimental effects of not truly understanding a text when devising language responses.

Trending

I sometimes wonder if we’ve successfully trained students in identifying language to the detriment of comprehending texts in their entirety, and what they’re actually about.

Equally, when it comes to other studied texts – notably Shakespeare – do students know what’s happening in any given scene and that scene’s purpose?

Sequencing and summarising exercises, quizzes, and ‘true or false’ questioning will help reveal misunderstanding.

Making revision effective

- Take time in lessons to demonstrate self-testing (even the old ‘look, say, cover, write, check’).

- Show students how to map a theme or character via colourful mind-maps, or by using images accompanied by text.

- Remind students that they can use their omnipresent phones to record verbal notes after watching online revision videos, or themselves talking through an essay before writing it.

- Encourage students to test each other, or have a family member step in. It doesn’t matter if nan doesn’t know the novel – give her a list of points on paper, and ask her to make sure you’ve said them all.

Jennifer Hampton (@brightonteacher) is an English teacher, literacy lead and former SLE (literacy). Browse great ideas to help with GCSE English Language revision. Download our AQA English Language Paper 1 ultimate revision booklet.

Planning and writing essays that fully demonstrate understanding

“Why on earth have they included that quote, when this one would clearly have been a much better choice?” Sound familiar? Here’s how students can avoid this and other issues, says Fiona Ritson…

Calling all English teachers: does this sound familiar? You’ve read a GCSE text with your class, and used resources you’ve painstakingly made in order to get them thinking more deeply.

As you go through extracts in the last lesson on Friday afternoon, you ask carefully crafted questions, and note with satisfaction how students shoot their hands up in a flash, like Barry Allen on the run.

You collect a pile of books containing essays, and plonk them in the boot of your car, smiling at the moments of brilliance you expect to see in your students’ work.

Later, back at home, you mark them. And that’s when your world comes to an abrupt stop. What went wrong?

Because what you are seeing doesn’t remotely resemble what you taught – were you even in the room? Why on earth have they included that quote, when this one would clearly have been a much better choice, leading to some fantastic analysis?

Could it be because you didn’t actually prepare them properly for what they needed to do?

All the way

Despite timetable constraints and pressure for schools, I strongly advise reading any GCSE text cover to cover with students.

This may sound obvious – but, blasphemous though many will find it, I’ve heard rumours of schools simply handing out extracts with summaries to bridge the gaps in missing knowledge and content.

However, the only way students will be able to write articulate essays is if they know the text inside out.

Moreover, whether we like it or not, pupils need to understand the exam specification. This doesn’t mean teaching to the test, but they do need to know what to do so that they can move up the levels on a mark scheme. This means recognising the language of that mark scheme.

Each exam board uses the same assessment objectives, but they’re weighted differently across the two papers for each board.

Some need context, some are a comparison, and so on. You and your students should know them inside out.

Plan, plan and plan

For the GCSE English Literature exam, students have to write an articulate essay to an unseen question, sustained over the whole piece, in about 30-60 mins (depending on question/exam board), showing clear understanding of the text and context, all whilst under pressure.

As teachers, we have to prepare them as much as possible. Five minutes planning an essay could ensure students don’t go off track because they’ve lost the question focus.

And teaching how to write effective introductions helps pupils not only to focus the start of the essay, but also to shape the direction and their ideas for the rest of their response.

Students need to consider the question, character or theme, at all times. A literature exam will always consider what the text is about – the actual content and themes or ideas the author is exploring.

The other consideration is how the text is written – so, the techniques used by the author through language, structural features, setting, characters etc.

Key elements to cover

Character

Students need to consider a character from many viewpoints; are they liked/disliked, and why are they important to the novel/plot?

Is there a theme explored through a particular character? How do we feel as a reader towards them? How are they treated by other characters?

And finally, do they change – do they learn anything across the story?

Themes

Learners must understand the themes explored in a text and how they are linked to the characters and storyline, as well as contextual information at the time of writing.

Language

This should be the easiest, the words on the page, but often students move swiftly past words or phrases, focusing on quotes that lead to poor analysis. Students need to look for key words/phrases that answer the question.

I’ve used a simple system for years. When I read the extract I begin to underline words or phrases that jump out at me.

Once I see a pattern, repetition, synonym or even antonym of a previously underlined word I circle it. This means when I get to the end I can quickly see key words/phrases and patterns across the text.

However, regardless of any little tricks they might use, students need to actually analyse the quote/words they’ve picked for meaning!

Techniques

Sometimes we get students to analyse language but for them the technique is an afterthought. Why did an author pick a metaphor or oxymoron at that point, how is that technique effective and, for example, how does the comparison add to overall meaning?

Structure/form

Analysing structure seems to present students with an especial challenge. They need to consider paragraphs, sentence types, punctuation, word order, clause order and how the extract begins and ends.

How does the genre of the text add to meaning or contribute to author’s intent? Does the extract follow a particular character’s thoughts or feelings and if so why; and more importantly, do they change over the extract?

Narrator

Here, students need to look for shifts in tone, subtle choices made by the author that carry as much impact as the words. Who is speaking and why? How does this add to overall meaning?

Setting

Where is the extract or that section set? Why is that important? How does it add to the atmosphere? Does it change the way characters think or feel?

I always advise students to pick around eight to ten quotes from across the extract or whole text covering language, techniques and structure – and remind them constantly that it’s not enough just to include a quote; they need to explain why it’s significant, too!

Finally, of course, students need to finish their essay with a conclusion that summarises the author’s intent covering the question and their initial introduction.

Additional support

For further help and guidance, try the following:

- Read Bringing Words to Life (Isabel L Beck, Margaret G McKeown, Linda Kucan) and Closing the Vocab Gap (Alex Quigley) if you haven’t already. Students need to understand tier 2 language; how to write about it and how to analyse it. They need to signpost their essay making strong connections in the extract or whole text.

- Get yourself on Twitter and find the English community using the #teamenglish hashtag, where teachers up and down the country share resources and their time freely.

- Sign up to Litdrive, a site where English teachers share resources.

Fiona Ritson is an English teacher in the south east of England. Find her on Twitter at @AlwaysLearnWeb.

GCSE English Literature FAQs

What is English Literature GCSE?

English Literature GCSE is a qualification taken by UK secondary students, focusing on the study of literary texts like novels, plays, and poetry. It involves analysing themes, characters and literary techniques and aims to develop critical thinking and writing skills.

How many English Literature GCSE papers are there?

There are two separate English Literature GCSE papers. The themes of each paper depend on which exam board you are with:

- AQA: Shakespeare and the 19th-century novel; Modern texts and poetry

- OCR: Exploring modern and literary heritage texts; Exploring poetry and Shakespeare

- Pearson Edexcel: Shakespeare and post-1914 literature; 19th-century novel and poetry since 1789

- Eduqas: Shakespeare and poetry; Post 19-14 prose/drama, 19th-century prose and unseen poetry

Do you have to retake English Literature GCSE?

It is not compulsory for students to pass GCSE English Literature. However, students must resit GCSE English Language the following November if they did not get a grade 4 or above and are still under 18.

Is English Literature GCSE compulsory?

English Literature GCSE is not a compulsory subject. However, the majority of schools require students to take it. English Language GCSE is compulsory.

How many quotes should you learn for English Literature GCSE?

Exam board Eduqas recommends learning three or four key quotes for each main character and theme.

What books do you study at GCSE English Literature?

What book you study will depend on your particular exam board, but common options include the following:

19th-century novels and prose

- A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

- Great Expectations by Charles Dickens

- Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

- Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

- The Sign of Four by Arthur Conan Doyle

- The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson

- Silas Marner by George Eliot

- War of the Worlds by HG Wells

Modern prose texts

- Coram Boy by Jamila Gavin

- Boys Don’t Cry by Malorie Blackman

- Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe

- Lord of the Flies by William Golding

- The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene

- To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee

- Animal Farm by George Orwell

- Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck

- Anita & Me by Meera Syal

- Woman in Black by Susan Hill

- Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

- Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha by Roddy Doyle

- Heroes by Robert Cormier

- About a Boy by Nick Hornby

- Resistance by Owen Sheers

- I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

- Ash on a Young Man’s Sleeve by Danni Abse

- Oranges are Not the Only Fruit by Jeanette Winterson

- How Many Miles to Babylon? by Jennifer Johnston

- Pigeon English by Stephen Kelman

- Chanda’s Secrets by Allan Stratton

- My Name is Leon by Kit de Waal