English as an additional language – How to ease EAL struggles

Hundreds of thousands of children arrive in our schools without the language they need. But training up young interpreters can provide the skills to support them…

- by Fiona Harris

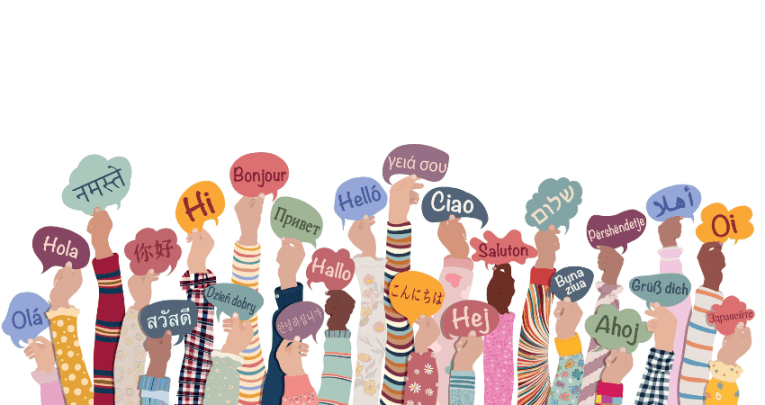

Hola! Buna ziua! Salama! Merhaba! Feeling lost? You’re not the only one. This is what every day can be like for children with English as an additional language (EAL).

Have you ever arrived at an exotic holiday location only to find yourself struggling to understand the locals or unable to ask where the toilets are?

Ever looked down at a menu to realise you haven’t a clue what any of the items are?

Arriving in a new country can of course be exciting. But for many it can be a daunting experience – particularly when we don’t speak a common language.

So how can we help those arriving in our classrooms with little or no English?

Teaching EAL

There are currently 1.6 million children in England who speak English as an additional language (EAL) (DfE 2021). Many of these have arrived with little or no spoken or written English.

How we welcome, support and teach these children is vital to their wellbeing. But it’s also important for their social and academic journey through school and later life.

Our city-centre school in the bustling heart of Cambridge has over 160 EAL children. And staff and pupils speak a total of over 36 different languages!

We welcome new pupils from across the globe every year, and have recently adopted a new approach to easing the transition into an English-speaking school.

Young interpreters

We have introduced a scheme training up a group of ‘young interpreters’ with the skills to support new children arriving with little or no English.

After being given a brief summary of the role, which includes being paired up with a younger child to help interpret, play games and introduce English vocabulary, an entire Y4 class were desperate to apply for the job.

They filled out a formal application form, to be one of these esteemed young interpreters.

The scheme is run by a member of staff who trains up the group. Not all the young interpreters are bilingual, and importantly they do not replace professional interpreters or bilingual staff.

They are, however, totally enthusiastic and overwhelmingly eager to help!

The young interpreters are paired up and then ‘buddied’ with a younger child who speaks the same mother tongue as at least one of the interpreters. This means that someone has a common language with the new child. This isn’t always possible, but we try!

Trending

Each young interpreter receives training on how to play with younger EAL learners. This includes how to do a tour of the school for new or prospective children and their parents; and how to use resources such as language picture cards to communicate with other children who are new to English.

I don’t know about you, but I do love a bit of ‘branded’ clothing that identifies a group I belong to.

The young interpreters are no different; they have identity badges and are fundraising for caps to wear to distinguish them and their role in the school.

This motivates the helpers to live up to their role of facilitating positive play, communication and integration across all cultures and languages in the school.

Supporting children with EAL

This scheme is reciprocal in its nature. EAL children welcomed into the school and able to speak their own language with another pupil. But the young interpreters are also empowered with the life-long skills to help others.

One young interpreter told me: “I’ve learned that you need to be kind to the children, and let them play what they want to play.”

Another reported that the younger children with English as an additional language had “made friends and have started learning more English words.”

It’s not all plain sailing though. The Y4 children are paired with those in Early Years or Reception, which is a considerable age gap and can cause some conflict.

But pupils are learning how to communicate. One Y4 admitted that “it’s not as easy as it sounds, but I’ve learned how to cooperate with younger children.”

Even during the early stages of its implementation, we have found that the scheme has already begun to support early learners with their language, communication and play.

These are incredible skills to learn, and the programme is an amazing opportunity to bridge the language gap, welcome new learners into our community and develop lasting cross-cultural friendships.

You can learn more about schemes in your area by searching ‘young interpreters’.

Fiona Harris is a teacher at St Matthew’s Primary School, Cambridge.