Questioning – 20+ strategies to encourage deep thinking

You might ask over a million questions over the course of your teaching career, but which types of questions are most effective?

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Teachers are professional question askers. Using questioning in our classrooms is a common strategy for getting our students to engage in critical thinking and self-reflection, and to become active participants in their own learning.

Indeed, questions are the tool in our toolkits that arguably do most to help activate the vital transfer of knowledge to support the teaching and learning process. We spend an estimated 40% of our classroom time in this question-response mode.

We ask roughly three questions a minute, 600 a day and 100,000 a year. So, if you’ve been teaching for ten years or so, then you’ve probably asked a million questions. Enquiring about the best way to question, then, is probably one of the best things we can ask.

Questions are an important cog in the assessment process. This is because the questions we ask and the answers these generate will often determine what we must do to close knowledge gaps. The verbal feedback we give, along with any follow-up ‘probing’ questions, are also key.

“If you’ve been teaching for ten years or so, then you’ve probably asked a million questions”

In far too many cases, we ask questions that have little impact on deep thinking and learning. The most worrying thing about this is that if we conduct it effectively, questioning can be one of the most powerful tools in our teaching armoury.

If we can question more effectively, the impact on learning is significant. So let’s explore different strategies that you can use to increase the quality and effectiveness of your questioning and bring about deeper thinking in your classroom…

- Understanding diagnostic questions

- Cumulative knowledge quizzes

- Open-response questions

- Reflective questions

- 15 more questioning strategies to try

- Why you should employ a ‘hands-down’ approach to questioning

- 16 instant feedback questions to turbocharge student progress

- Five core powerful questioning principles to adopt

Understanding diagnostic questions

You can design diagnostic questions to:

- assess students’ prior knowledge

- identify misconceptions

- gauge pupils’ understanding of a particular topic of study

They’re a powerful tool for both teachers and students to understand where they stand in their learning journey.

One way you can use diagnostic questions is at the beginning of a lesson, as part of a ‘do now’ activity. The questions you conceive for ‘do now’ activities will typically be low-stakes recall queries. These activate prior knowledge, and help you to check for understanding before teaching new information.

Examples of diagnostic questions in action

For example, imagine you’re getting ready to teach a Y8 class a new unit on hazards in geography. You want to check if your students have remembered some of the key processes that cause hazards to occur. You’ll then build on this knowledge to look at the formation of a tsunami.

Using diagnostic questions in this scenario will be important for you to determine if you need to reteach the foundation knowledge before diving into the next part of the curriculum.

The knowledge you gain from asking these low-stakes questions should help you tailor instruction to meet the needs of your students. Here’s some examples of diagnostic questions you might include:

- Which crust is denser – continental or oceanic?

- When one crust moves underneath another, this is known as…?

These two diagnostic questions will help you check students’ prior understanding before moving on to the main information you want them to learn in this lesson. You may also want to use some ‘do now’ questions to check for common misconceptions in your subject.

Here’s another example of diagnostic questions in action, as told by Geoff Petty, author of How to Teach Even Better: An Evidence-Based Approach.

You’ve just taught pupils how to calculate the area of rectangles and squares in maths. You put the following statements up on a screen and begin by asking pupils which of these statements are true and which are false:

- Area is length x height for a rectangle

- 2 metres x 2 metres is ‘2 square metres’

- For a square, area is twice the length of one side

- Area is measured in units of length, such as centimetres or metres

- For a rectangle, the area is always a bigger number than that for its perimeter

- Area is the two-dimensional space occupied by a shape, in square units

You’ll notice that there are some common misconceptions in these statements (the second one, for example). You should design these statements to stretch students, but not too much.

Because there are six statements here, the chances of a pupil guessing correctly which are true and which are not is one in 64 – not likely! Here is the procedure you can use with these statements:

- Pupils work alone to decide which statements are true and which are false

- Students then discuss their answers with a peer, exploring disagreements

- You take each statement in turn and ask pupils to display their thinking by putting their thumbs up if they agree or thumbs down if they disagree. Children all display their thumbs at the same time

You can scan the thumbs and use this feedback in several ways. If all pupils have the answer correct, skip to the next statement. If there is disagreement, start a class discussion. For example, ask, “Paul, why do you think point two is correct? Mohammed, why don’t you agree?”.

If there is still confusion, you can reteach the point before moving on to the next statement.

Targeted interventions

By posing diagnostic questions in this way, you can pinpoint any misconceptions or misunderstandings that students may have.

The insights gained from asking these types of questions will enable you to more precisely target interventions aimed at addressing these issues. This allows for more effective and responsive teaching.

- Start with the question, “What do I want my students to know?”

- Planning backwards from the answers you’re looking to cultivate allows you to consider the best way to ask your question.

- Remove any barriers to making that question effective. Cross-check with other specialisms to avoid misconceptions and remove unnecessary vocabulary.

- Once you’ve struck question gold, don’t move on. Think about asking that same question in a variety of contexts for differentiation and practice of skills.

- Never forget that questions and answers mean nothing without responses from teachers.

- Nurture a questioning culture. You will know you’ve had an outstanding lesson if you were not the only one asking the questions.

- Thanks to Elisabeth Pugh, curriculum lead for science at Learning by Questions

Cumulative knowledge quizzes

You can use diagnostic questions in the context of cumulative assessment, for both formative and summative purposes. Cumulative knowledge quizzes create an opportunity for you to assess whether students can remember the nuts and bolts of the curriculum you’re teaching.

When drafting diagnostic questions for these kinds of knowledge quizzes, it can be useful to keep the following component structure in mind:

1: Current knowledge

2: Prior knowledge

3: Explicit subject vocabulary

You can base the questions you use in these assessments on two formats – open response and multiple choice. Open questions allow students to respond with greater freedom and in more detail, drawing on their prior knowledge.

Here’s some examples of open-response questions:

- What is urbanisation?

- Why do we use semicolons?

In contrast, closed questions look like this:

- Which of the following is the correct definition of urbanisation?

- Romeo is from the House of Capulet – true or false?

Open-response questions

Open-response questions require pupils to think harder. This is because the lack of plausible answers means they’ll need to recall without any prompts.

However, they do also allow students to demonstrate wider knowledge. This is particularly true when there are multiple options for students to pursue when providing their answers.

You can use multiple-choice questions, on the other hand, to determine common misconceptions by presenting plausible distractors. When devising the diagnostic tests for these assessments, though, your aim should be to create questions that promote more than just the reciting of facts and details about your subject.

The tests ought to provide enough of a challenge that students are prompted to really think. This, in turn provides better insights for you as their teacher. You can then build on these to become more responsive to them in the next part of the learning journey.

Reflective questions

During a lesson you might also want to use reflective questions. These are questions that go beyond the surface level and promote metacognition – the ability to think about one’s thinking.

Reflective questions are often useful when asking students to consider the key points of the lesson just gone. This opportunity for reflection lets students reflect on what they’ve just learnt. At the same time they can consider the areas in which they’re strongest and any areas for further development.

However, asking students to merely reflect on their learning without guidance is likely to be ineffective. This is because students need clear criteria in order to reach an accurate judgement.

This is where the use of success criteria for application tasks can guide reflection. This form of self-assessment will then empower students to take ownership of their own learning and make any necessary improvements.

15 more questioning strategies to try

What’s the question?

This is a simple, five-minute starter activity to get a group talking and confident. You give your class an answer (one word works best) and ask them what the question is. In small groups they come up with as many plausible suggestions as they can.

There can be a competition to see which team has the longest list, to add a sense of rivalry and further engagement.

For example, an answer could be London. The questions could be factual, such as ‘Where is parliament held?’, or personal, eg ‘Where did I visit last Easter?’ Both encourage talking and the sharing of ideas.

Give them cards

First, consider how many questions you will want to ask for a Q and A session. This is likely to be an approximate calculation, as additional questions will flow as student confidence grows and so in turn does the discussion.

Count up the number of students you have. Divide the number of questions by the number of learners, rounding up or down accordingly.

You may think you only have ten questions for a group of 25, in which case just give each student one card and, if appropriate, expand the discussion as you go.

The aim is for the students to get rid of their card(s) and to do this by answering questions. As students respond to a query you take their card away from them. Once they have no cards left they can’t answer any more, but everyone needs to answer something.

This means the longer you hold your card, the fewer questions will remain, and so your choice of which you answer becomes increasingly limited. This encourages students to get involved from the start and to know that they will have to engage.

Hand out raffle tickets

Another approach is to give students tickets for answering questions, either correctly or for giving it a go. This requires more attention to ensure all students get involved, but works well across a whole session.

At the end of the session, you draw a winner. The more the student has engaged with the lesson, the more tickets they will have, and so a bigger chance of winning a small prize.

Pass the mind-map

This technique allows you to create information-rich pieces across a whole group in a relatively short time. Place students in groups. Twos or threes work best, but it will depend on the size of your class and the number of mind-maps you want to have completed.

You will need several different questions or starting points, one per sheet. Students will pass these between groups, so each mind-map offers something new to consider.

To begin with, students will find it relatively easy to come up with answers, but as the sheets are passed round and other groups have already filled in the most obvious responses already, students will need to go further in their discussions.

They also need to read the mind-maps before adding their own comments to ensure they don’t repeat ideas.

When I do this I then use either use the work as a display or ask students to photograph the information, which they then use as references for their own pieces of work.

Who likes McDonalds?

Many students feel they can’t analyse. They may struggle to break down work into when, why, what and how – but most of them can talk about McDonalds indefinitely…

So start by questioning them on a topic they feel confident about – that doesn’t scare them.

- When did you last go to McDonalds?

- What did you eat?

- Why did you pick that?

- Are they any bits you don’t like?

- What about the gherkins?

- And did you have a meal deal?

- What drink?

- And why did you pick that?

- But what about KFC?

- How do they compare?

Before you know it you have a detailed piece of analysis and a clear demonstration for your students that they do have the skills they need to engage with your subject, too.

Then tell students the subject-based Q and A follows the same process. Do one related to your subject immediately if you can to embed the process and the belief that they can answer questions and talk about a subject effectively within the group.

Randomiser PowerPoint

While Q and A can offer us subtle ways to add differentiation into a session, because you can aim questions at certain students according to their level of ability and engagement, sometimes we can overthink things. We might unintentionally not push those we believe to be weaker.

A randomiser PowerPoint removes you from the process of allocating the questions, selecting the student who is asked to respond for you. This keeps everyone engaged, in the expectation that they will have to answer questions sooner or later.

Some programs offer you the opportunity to mark answers as correct or incorrect, meaning that those who get a question wrong will come up more often until they start answering correctly.

This can have issues if a particularly weak learner is in your class, but if you use it well you can give students a real incentive to be clued up on your subject, ready for whatever questions the process might throw at them.

Thanks to Hannah Day, head of visual arts, media and film at Ludlow College, for the above ideas.

Pause, pause, share

We know from research that the use of a ‘wait time’ after asking a question can increase the amount of thinking time and the level of participation of pupils. A second wait time increases both even further.

A simple way to remember this is Pause, Pause, Share (PPS):

- P – ask a question and pause, without giving or taking an answer.

- P – signal you will take an answer from a targeted pupil, but instead of indicating if the answer is correct, ask the group if it is, or if anyone can expand on it. Now insert a second pause.

- S – take a final answer from a targeted student and share and expand upon it with the group.

Hands down, heads up

The normal ‘hands up’ routine, where you ask a question and any pupil who knows the answer shoots their hand up immediately, is unproductive. It often means the same students are answering over and over again, whilst not allowing time for others to think about the answer.

Instead, try a ‘hands down heads up’ strategy: inform the class that the question you are about to ask requires thinking about and will require everyone to have an answer (not just the usual suspects).

After asking the question, give a sufficient wait time to allow everyone to think through his or her answer. Then use a random name or targeted name strategy to choose who you want to answer the question.

Plan to succeed

Pre-plan your questions, and target them to specific groups of learners to be most effective. An often-quoted example of good practice is that of Japanese teacher planning, where groups of colleagues plan questions together.

The jugyou kenkyuu or ‘lesson study’ allows teachers to pre-plan and discuss deep, probing questions designed to enhance learning.

Central to this concept is that assessment is built into the process of learning and not at the end. Using ‘question plans’ as opposed to a ‘lesson plan’ to structure a lesson prioritises learning above the functional aspects of planning. It ensures learning is prioritised by remaining the key focus.

Use wicked questions

Questions deliberately designed to provoke thinking whilst demonstrating evidence of learning and deeper understanding are sometimes known as wicked questions. They are used to used to challenge assumptions that may not be sustainable. These are questions:

- where there is more than one answer

- that deliberately provoke or divide opinion

- that may present a paradox

Examples include:

- Is there more love than hate in the world?

- Is it okay to bully a bully?

- If your brain were to be put into another person’s skull, and vice versa, which person would be you?

- Does charity simply increase the need for charities?

Thank you to David Spendlove for the above ideas. David is author of 100 Ideas for Secondary Teachers: Assessment for Learning.

PPPB

PPPB stands for pose, pause, pounce and bounce. You pose a question. Pause to give thinking time. Pounce the question onto a student of your choosing. Finally, you bounce their response to another student to generate discussion.

To get even greater depth of thought, you can keep the ‘bounce’ stage going as long as you want. You only provide the ‘answer’ (or your view of the answer) after the ‘bounce’ stage.

Pair checking

Students first work individually on a higher-order question, then share their answer with a partner. Each partner gives the other feedback, something positive ‒ WWW (What Went Well) – and something that could be improved – EBI (Even Better If…). You then give the correct answer. At this point, the pairs give each other another EBI.

Pair checking can easily turn into quad checking. This is when a pair shares their answers with another pair using the same feedback process.

Buzz groups

If done right, as the label suggests, these groups create a buzz of industrious conversation. Students work in small groups on a higher-order question. To promote task focus, it’s a good idea to make the question time-limited (and stick to it!).

Following the group discussion stage, take a partial answer from each group:

Can this group tell me one disadvantage arising from the use of fossil fuels? This group, another advantage. Your group, one reason why they continue to be used? Another reason from this group. And lastly, from this group, give me a disadvantage if we stopped using fossil fuels tomorrow.

In the example above, volunteers answer from each group, but it is just as easy for you to nominate a student. If a student thinks that they might have to speak for the group, they are more likely to pay attention because if they don’t, they could let the group down.

Don’t provide the full answer until the end of the whole process. Nomination can happen at the time of group responses (as above) or when you initially set the question. This latter approach is particularly helpful if you have a student who has been coasting (nominate them) or a student who has been too dominant (don’t nominate).

Assertive questioning

This is an extension of buzz groups, but the difference is that once teams have given their answer, they then have to come up with a class-wide consensus answer.

As the teacher, take a critical role, pointing out differences and inconsistencies in group responses, bouncing responses from one group to another, and playing devil’s advocate if necessary. Only give your answer once a consensus has been reached.

Assertive questioning is high in student participation, provides plenty of thinking time and discussion, and is excellent for higher-order questions.

Thanks to Robin Launder for the above ideas. Find Robin at behaviourbuddy.co.uk and follow him on twitter at @behaviourbuddy.

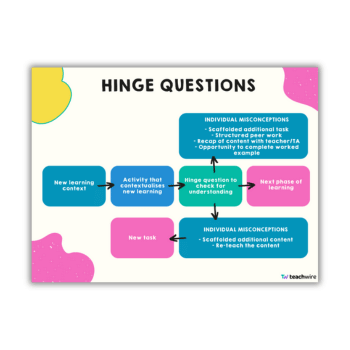

Hinge questions

Deciding whether something has been learnt to the required level can be done through some effectively placed hinge questions.

Hinge questioning lets you decide the direction of the learning – focus your hinge question(s) around key concepts, ideas or skills to check if the class is ready to move on, or if you’ll need to recover parts of the learning. Read more about hinge questions.

Thanks to Adam Riches, senior leader for teaching and learning, for this idea.

Question basketball

After individual thinking or think pair share, invite a child to share their ideas with the class. It’s here you introduce the ‘basketball’ moment. Encourage other pupils to ask that child a clarification question or statement, such as:

- Can I just check I’ve heard you accurately? Did you say…..?

- I’m not sure what you mean by the word ‘X’. Please can you explain?

- I got lost after the first sentence. Please can you repeat your idea?

In this scenario, this child is the point guard – the player who dribbles the ball up the court to start the play. The challenge is to ensure that all children in the class understand the contribution they have made.

This may well involve several passes of the ball amongst the class. Taking the time to listen and understand in this way can often represent a big shift in classroom dialogue.

Then, once you are satisfied that everyone has understood, invite children to build on the first idea or offer a new idea to help develop the answer to the original question.

Once you have established this key skill with children, you can then further encourage a basketball approach by using strategies such as:

- modelling the process with a small group of children to the whole class

- making a video recording of the classroom dialogue and reviewing it together with pupils

- gradually building a crib sheet of useful questions

- building the basketball approach across your whole curriculum

Thanks to Jennie Pennant, director of GrowLearning, for this idea.

Why you should employ a ‘hands-down’ approach to questioning

Think back to your own days as a pupil in the classroom. If you knew that your teacher was always (and only ever) going to pick people to answer questions with their hands up, then you could quite quickly work out that if you didn’t want to think or participate, you just had to keep your hand down.

Worse still, if, as teacher, you judge whether to move on in your lesson by asking a couple of questions and getting a correct answer from one enthusiastic or knowledgeable student, then your formative assessment can hardly be classed as robust or inclusive of all students.

This is where a ‘hands up’ strategy of questioning really fails in the classroom. It should be your job as teacher to judge what everyone knows about a certain topic, question or problem; not just what a few enthusiastic children want to tell you.

By employing a consistently implemented ‘hands down’ approach to your questioning, all students need to be thinking about the answers to your questions all of the time, in case they are picked to contribute to the classroom discussion.

Thinking time

The reason you ask a question is, of course, because you want an answer. So when a child thrusts their hand in the air enthusiastically the second you’ve asked one, it can be extremely tempting to take a quick answer from them.

This happens far too often. In fact, studies have shown that the average time between asking a question and getting a response in the classroom is less than one second.

“All students need to be thinking about the answers to your questions all of the time”

This presents us with many problems. Firstly, how can anyone give you a well-thought-out answer in less than one second? Secondly, everyone in the class needs time to think about the question that you’ve just posed.

By taking an answer so quickly, you’re depriving the vast majority of pupils any time to think before the answer is given. Allowing for short periods of wait time before you ask a child to contribute an answer makes a significant difference to the quality of answers that you receive.

Dangerous ramifications

Through his significant and extensive work on formative assessment over the past two decades, Dylan Wiliam has found that a lack of effective wait time when questioning students leads to a culture of children quickly raising their hand to answer questions. More importantly, teachers only ask for responses from students with their hands up.

This quick-fire culture of rapid questioning means that pupils who don’t want to think don’t have to, because they know that the answer or another question will come along almost immediately.

“By taking an answer so quickly, you’re depriving the vast majority of pupils any time to think”

To lots of students, this signals that there is no point in trying in the first place. They can just sit back and leave the most enthusiastic pupils to answer.

For many children, this approach also minimises the risk of potentially getting an answer wrong in front of their peers.

Therefore, not only is this unproductive questioning the catalyst for a lack of cognitive engagement from many students, but it also has potentially dangerous ramifications for us as teachers if we base our dynamic formative assessment on it.

If questioning is only actively engaging a minority of children in your classroom, then any responses you gain from them are not a good enough sample size to determine the knowledge and understanding of the whole class.

By consistently combining wait time with a new ‘hands down’ approach to your questioning, you can empower yourself to use questioning as a highly effective formative assessment tool. Now you can get a handle on what the whole class knows, rather than just a select few individuals.

You can then use this information to inform your dynamic and responsive teaching strategies.

- Start by explaining to pupils that you’ll be using a hands-down approach from now on. You’ll be in charge of who will be answering the questions, so that means everyone needs to be thinking and listening because they never know who is going to be asked next.

- Make sure you select different children to answer for different reasons. You may want to start with a higher or lower-ability student for a specific reason, or you may choose to target some of your pupil premium students. There’s also the classic reason: “I’ve picked you because I saw you weren’t paying attention.”

- To ensure pupils don’t feel threatened or anxious about being picked, give them a nod or have a quiet word to tell them you are coming to them next. This way they can get themselves mentally prepared, switched on and ready to answer.

Jon Tait is deputy headteacher of a secondary school and author of Teaching Rebooted (Bloomsbury Education). Find him on Twitter at @teamtait.

16 instant feedback questions to turbocharge student progress

All too often we as teachers spend much more time marking than our students do digesting and acting upon that feedback. Now is the time for change: make the students think, and embrace the struggle that is an essential aspect of improvement.

Below are some examples of questions I like to use in my own marking and feedback:

- How could you have approached this task differently?

- What have you learnt from completing this task?

- When you read this back, what would you have changed to improve it?

- How does this link to the assessment objectives?

- If you look at the assessment framework and consider the level above what you achieved, what one thing would you easily be able to do to move yourself into that grade boundary?

- Can you highlight what you have been successful in; linked to the assessment objectives what would it be?

- Looking back at your work and my feedback, what advice would you give someone starting this task?

- What is your personal highlight in this piece and why?

- Can you choose one small section of this piece of work and rewrite/redraw/redo it to improve it?

- If you could give yourself one target for improvement, linked to the assessment objectives, what would it be?

- If you had to grade this piece of work, using the assessment framework, what grade would you give it and why?

- Is this statement true or false? [Insert a statement to assess the key piece of knowledge you have imparted]

- When you read this piece back, what stands out to you? Why do you think that is?

- What did you not understand or struggle with while completing this work?

- If you had to reorder this piece of work how would you do it and why?

- And in response to any answer the student gives to the above questions… why?

Students are wiser than they, and often we, consider them to be. Always remember that ‘feedback should cause thinking’ (Wiliam) – and if it doesn’t, then what is the use?

Sarah Findlater is a senior leader and an English and media teacher; and the author of Marking and Feedback – part of the Bloomsbury CPD Library Series.

Five core powerful questioning principles to adopt

Sequencing

- Before asking questions, take time to plan out the low to higher-order questions you intend to ask. Aim to work with colleagues in your department to develop these questions during curriculum conversations. Practise using them to build the clarity and confidence that will yield the responses you are looking for.

- During a lesson or series of lessons, consider using a mix of questions, both low and higher order, so they address all cognitive demands while keeping in mind the desired learning outcome. For example, begin with a series of recall questions, like “What is…?” before moving on to questions that require a greater degree of thought, such as “Why might…?”

- Consider pupils’ prior knowledge before devising questions, taking into account how the questions you plan to ask will build on foundation knowledge.

Presenting and framing

- Distribute questions with the aim of involving as many pupils as possible during a question-and-response session. Use different strategies like cold calling, hands up, choral responses and think, pair, share.

- Frontload questions to pupils by explaining what you are expecting from them. This will help build a responsive culture in your classroom. For example, telling them that you are looking for a hand up/hands down or a class vote before asking the question.

- For higher cognitive questions used with application tasks, spend some time unravelling the command of the question and what success would look like before the pupils begin independent practice.

Pausing

- Teachers should demonstrate what ‘wait time’ means by live modelling to pupils during class discussions. For example, when a pupil asks a question, pause before giving a response. This will encourage them to appreciate why pausing between asking and answering a question can help to address non-explanatory responses, and to see the process in action.

- Research indicates that the quality of a response increases when wait time is three seconds or more. With this in mind, teachers should judge whether the pupil will need a shorter or longer time to respond. Base this on the type of question asked. E.g. when asking a pupil a more cognitively demanding question, provide a longer wait time in comparison to asking a knowledge recall question.

Gathering and processing

- Use a mix of questioning strategies to field questions and gather responses from pupils. Be strategic about to whom you ask questions to encourage classroom participation. Remind pupils of the role that oral responses play in the learning process.

- Develop a culture where non-explanatory responses are unacceptable and pupils are encouraged to provide a full answer.

Redirecting

- If a pupil struggles to answer a question, redirect it to another pupil and then return to the original pupil to either clarify or expand on the initial question. Provide a prompt to pupils like, “Take a moment to think back to what we learned last lesson…”

- When using diagnostic quizzes as part of an assessment for learning model, look for common errors across a teaching group. Revisit these in subsequent lessons as part of your daily review or for reteaching a component of the curriculum.

Through the careful implementation of these strategies, you can create the conditions that will promote learning and retention over time.

Michael Chiles is a school leader, principal examiner and author of Powerful Questioning: Strategies for Improving Learning and Retention in the Classroom.