Differentiation done right – How to teach mixed ability MFL lessons

Jennifer Wozniak-Rush breaks down the steps she follows when teaching her MFL lessons to mixed ability classes

At some point in our career, all of us will have heard the words, ‘Mixed ability teaching doesn’t work!’ – or perhaps that closely related phrase, ‘I hate teaching mixed ability classes!’

It’s my belief that we shouldn’t ‘label’ pupils through setting, and that teaching mixed ability classes doesn’t amount to us placing a cap on what pupils might produce. It’s common practice in primary, so why shouldn’t the same apply at secondary?

In my school, we teach mixed ability classes from Y7 right through to Y11. As a result, I’ll spend time carefully examining my seating plan and ensuring that pupils of similar abilities aren’t sitting together.

Instead, I try where possible to seat a ‘high ability’ pupil beside a ‘middle ability’ pupil, and a ‘middle ability’ pupil next to a ‘lower ability’ pupil. This can help facilitate some safe coaching and mixed ability group activities, thus encouraging a climate in which pupils feel able to support one another.

A range of routines

In class sizes of 32, however, it can be easy for some pupils to hide and keep their heads down. Our role as teachers is to ensure every pupil has ample opportunity to contribute in class, and to speak as much as possible in the target language.

I’ll use a range of routines in my MFL lessons – set greetings, a consistent registration procedure, ‘What are we going to learn?…’ announcements, pre- and post-pair work routines – and regularly ask random pupils to contribute to the lesson; something they’re generally confident in doing, given how frequently I call upon them to do so.

Lower ability pupils may give simpler, but accurate answers, while others might offer more complex responses. Over time, the effect of this is to gradually make the language used by all pupils in the room better and more sophisticated.

Naturally, languages are meant to be spoken, but I’m also conscious that some pupils are much more reluctant to put their hands up and have a go. With that in mind, I’ll try to incorporate as many pair work activities into lessons as possible, so that everyone can practise the vocabulary, get involved and hopefully build their confidence in speaking another language.

Teaching to the top

To engage all pupils, it’s important to set the big picture and make language learning meaningful.

At the start of each academic year, I’ll ask my pupils about their interests and what floats their boat, and then use this information when planning lessons. Pupils don’t want to learn about ‘buying souvenirs’, as this isn’t something they’ll tend to do.

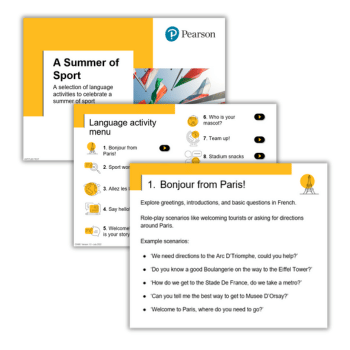

Instead, they’ll want to be able to talk about topics that are relevant to them. We don’t follow a textbook in KS3, which allows us to be more creative and teach topics of greater relevance and interest to our pupils – the internet, for example, or sport, socialising with friends – things they can relate to.

We study a film with all our KS3 classes, and aim to bring in as much culture as possible throughout the year. We try hard to get our pupils demonstrating the skills we’ve taught them, within the context of topics that interest them.

One key benefit I’ve found of mixed ability grouping is that teachers can set the same high expectations and offer the same tasks to all students, regardless of prior attainment. It’s an approach based around ‘teaching to the top’ and having scaffolding in place to help those pupils who need it.

I find it much more effective to ‘teach to the top’ and regularly check what I need to do to make the lesson content accessible for everyone in the class – such as using writing or speaking frames, giving extra guidance or engaging in further discussion.

Scaffolding is key, but let’s not forget that at some point that support will need to be removed so that pupils can work independently.

Questioning and feedback

To me, differentiation in mixed ability settings is best practised via questioning and feedback. Questioning is a hugely powerful tool, particularly in mixed ability MFL settings.

I’ll call upon a range of strategies, such as ‘Cold Calling’ and ‘No-Opt Out’ – both ideas taken from Doug Lemov’s Teach Like a Champion.

Cold Calling tends to be my default mode for most questions, and operates on the basic principle of ‘No hands up!’ I’ll ask questions and then select those pupils I want to answer, thus avoiding the pitfalls that come with hands going up and calling out.

Who I select to respond will be based on my knowledge of the class, and ultimately ensure that all pupils are involved at some point – from those at the front to their peers at the back, alighting on the shy, the confident, the loud, and know-alls as we go.

No Opt-Out is reserved for when a pupil gets an answer wrong, or partially wrong. The teacher turns to another pupil to answer, and then returns to the original pupil to give him or her a chance to offer the correct answer.

This is a useful technique in MFL lessons, as it gives pupils another opportunity to repeat the language.

It also helps avoid the otherwise common occurrence of Y9 pupils responding with, ‘I don’t know!’ – not because they genuinely don’t know, but because they don’t want to speak French – and get away with not giving an answer.

Think, pair, share

When posing more challenging questions, I’ll do a Think Pair Share so that all pupils have an opportunity to think about the question and discuss it with a partner, before I ask pupils at random to share their answers with the class.

This helps to build confidence, since pupils feel reassured by knowing, before the teacher asks them, that their answer in the target language is the same as the person next to them.

It also works well when looking at grammar, on those occasions when you want pupils to work out a grammar structure for themselves, rather than simply explain it to them.

If I want to engage with a larger number of pupils within a lesson, I’ll call upon the ‘ABC technique’. This involves a pupil first giving me an answer in French or Spanish.

I will then ask the class if they agree with the answer given and the language used, and after that, ask who can build on it by either giving extra details in the target language, or a justification for the opinion given.

Following this, I’ll ask if any pupils can challenge, or provide a contrast to the answer that’s been given.

I might ask for an antonym, or request that they change a masculine word for a feminine one, and work out with the class if other words in the sentence will now need to be changed as a result.

As Dylan Wiliam once observed, “Everything works somewhere, and nothing works everywhere.” I’ve found that engaging all pupils depends upon knowing your classes well, and finding those strategies that work best for the pupils you’ve got in front of you.

The best engagement tool

I use mini whiteboards with all of my classes in every lesson. Each pupil at our school brings their own mini whiteboard and marker pen with them to class, though there are a growing number of online services and solutions that can model the functions of whiteboards electronically (including Spiral and Whiteboard.fi, among others).

We use mini whiteboards to:

- Check understanding

- Work on misconceptions

- Check spelling

- Set translation activities

- Write sentences

- Practise grammar

- Illustrate descriptions

- Comment on others’ work

As well as ensuring everyone has to take part, the students’ use of whiteboards enables me to easily spot see any potential misconceptions that I can address there and then, or in my future planning.

For maximum efficiency, I instruct my pupils to only show me their whiteboards when I say so. That way, everyone is given sufficient time to write their answers, and pupils are prevented from copying their classmates.

Jennifer Wozniak-Rush is an assistant headteacher for teaching and learning, and an SLE in MFL.