Descriptive writing KS2 – Emma Carroll

Before pen even hits paper, it’s the thinking, planning and wondering that really makes a difference to creative writing lessons, says the author and former teacher…

- by Emma Carroll

‘Oh no, miss, not again!’ Yup, this was the common reaction to my creative writing lessons.

I don’t mind telling you: I’m not proud! Though I loved teaching English for nearly nineteen years, there was a point when I realised I was a writer trapped in a teacher’s body, and no amount of enthusiasm for writing on my part was going to win over the majority of my students.

Yet it wasn’t until I started taking my own writing seriously that I began to see why I’d failed at teaching my students to do the same.

It wasn’t enough to give them just a lesson, a title, a theme. Nor was it right to focus so much on language use, structure, editing their work, when we’d completely ignored the very first part of the writing process.

Warming up

So much of the work in creative writing is done before your pen even touches the page. Ideas need to grow. Worlds must be built.

We have to get know our characters. This takes time. It’s messy. It might involve scribbling notes, drawing mind-maps, listening to music, looking at pictures, reading other stories.

For each book I’ve written, I have notebooks full of this stuff: it’s illegible scrawl, mostly, but it’s also the true starting point for the story I’m trying to create.

These days, as a full-time author, I’m often asked to deliver writing workshops to KS2 children, and I love to do so: it’s one of my favourite parts of the job.

Teachers will ask me to mention editing because it’s an important part of the writing process. But what I’ve learned through my own experience is that editing – and writing – comes later: first, we have to nurture our ideas.

I tell students it’s like warming up for a football match – that to give your best performance, you’ve got to be fully prepared.

‘What’s the title, miss?’ a keen student might ask, pen and ruler poised.

‘There isn’t one,’ I tell them.

‘So what are we going to write?’

‘Nothing yet,’ I’ll say. ‘You’re going to think.’

First, I ask the class to think of their favourite book, and then explain that this choice alone might shape the type of stories they’re drawn to, and therefore more likely to enjoy writing.

Then we’ll consider other personal traits – likes and dislikes, talents, fears and dreams. All these things make us individuals, and will in turn help make our writing unlike anyone else’s.

It’s also worth mentioning that characters in stories will often have traits and quirks that somehow relate – directly or through association – to the author’s own experience.

In other words, YOU are a great resource when it comes to creative writing. Set scenes in your favourite places or in countries you’d like to visit.

Give characters interests or talents that are yours: it makes writing them much more fun.

Words and pictures

Next we look at interesting pictures, images I’ve found online of mysterious-looking places, or of someone who looks as if they’ve a story to tell.

In fact, the task works with any picture, just as long as its intriguing enough to catch your class’s attention. I’ll ask three simple questions:

What type of animal is just out of shot?

Why is the date 13th June important to this person or place?

If you were in this scene what would you hear?

You can extend the questions (or adapt them), change the pictures, add a second picture and ask how it links to the first.

Trending

All the time re-iterate to students that there are no right or wrong answers- they are simply using their imaginations.

Pick a genre

To give the session further focus, I might then nudge students towards a specific genre of writing – in my case, historical fiction, as that’s the genre I write myself.

This can work well if you’re studying a particular period – WW2 for example – since students will already have some knowledge of the period.

Historical fiction is all about creating a world that’s a slightly altered version of our own. It’s not the dry, history-book facts, but the everyday domestic details of what it felt like to be alive at that time; food, clothes, sights, smells, views from the bedroom window, favourite item of clothing, what you’re scared of, what you want more than anything.

In incorporating a genre’s traits and stylistic features, it really can make for better, more sophisticated outcomes than just ‘writing a story’.

World building

By the time students have built up a ‘world’ for their character to exist in – this might include maps, house plans, lists of era appropriate words and phrases – the ‘writing a story’ part feels so much easier.

In fact, it can feel like taking the brake off, as students dive into the worlds they’ve created. At the point where they’re ready to write, they’re invested in their stories.

I’ve seen this stay with them through the editing part, too, because they’re able to see that at each stage their work is improving.

Yes, the process takes time, but the end result is worth it, because the students are surprised – and delighted – in what they’ve achieved.

The very best creative writing comes when you truly connect with a concept. It’s not just about a cognitive understanding of the task. It’s about feeling it, getting a buzz from your best ideas.

All this takes time, space, a bit of digging around, exploring and playing with what gives you inspiration.

I’m sure there’s a baking metaphor for it: the better the prove the better the rise or something. Or maybe I’m just looking forward to the new series of Bake Off a bit too much…

5 quick-fire writing exercises to get students thinking creatively

- Show your class an old black-and-white photo of a person and ask them to tell you three things about it: what’s the person’s name? What are they looking at? What are they hiding in their pocket?

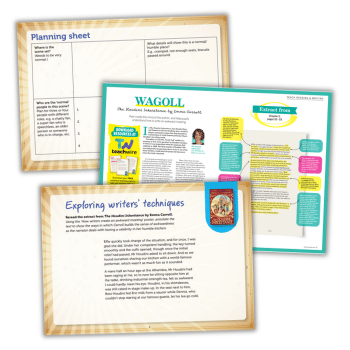

Emma Carroll is a bestselling, award-winning author, with 20 years of teaching experience. Download a WAGOLL resource pack based on Emma’s novel The Houdini Inheritance.