Attachment disorder in children – Advice for teachers

Learn about attachment disorder in children and try these supportive classroom strategies to help…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Children with attachment disorder may struggle with trust, emotional regulation and building relationships. This can affect their behaviour, focus and learning. Here’s how to spot it and what you can do to help…

What is attachment disorder?

Attachment disorder refers to difficulties in forming secure emotional bonds with others. It often results from early experiences of neglect, abuse or inconsistent caregiving.

Attachment disorder is not always easy to understand and can be challenging and emotionally draining for the adults working with the child.

However, taking time to invest in building positive relationships with these children means they are more likely to succeed. If you can champion these children, you will be creating a safe, secure and inclusive classroom.

Read more about becoming an attachment-aware school.

Attachment disorder symptoms in children

Many children who have an attachment disorder show both an avoidance of intimacy and extreme attempts to control close relationships coercively.

They may use threatening, angry or menacing behaviours and/or seductive, charming or demanding behaviours.

As close relationships for these children have often led to abuse, fear and hurt (shame and rejection), they can equate closeness with distress or danger. Intimacy becomes something they need to resist.

The closer you try to get to a child with attachment disorder or the more love you show, the more threatening you become.

Vicious cycle

Nevertheless, children with attachment disorder are also often uncomfortable with too much distance from their caregiver.

A vicious cycle often ensues, whereby they draw their caregiver closer through demanding or charming behaviours, only to distance them when they come too close. They then draw their caregiver back in when the distance (physical and/or emotional) becomes too great again.

A child with attachment disorder may demonstrate behaviour that serves to:

- demand attention and a response to their needs

- punish and distance their caregiver

- release pent-up frustration and anger

Diffuse attachments

Other children who have an attachment disorder exhibit diffuse attachments. This is signalled by indiscriminate sociability and a marked inability to exhibit appropriate selective attachments.

These children can appear charming and gregarious. They’re likely to be excessively friendly towards strangers and do not appropriately select an attachment figure if they’re hurt, unwell, frightened or hungry.

Where care arrangements change (for children in foster or adoptive care, for example), children who have an attachment disorder often compulsively re-enact their usual behaviour with their new caregivers.

Like other children, they feel safe and reassured in association with people behaving in predictable and expected ways.

As they expect caregivers to be angry and threatening, or undependable and rejecting, they often behave in a way that encourages similar behaviour in their new caregivers. This confirms their belief systems, which is reassuring. It also perpetuates the cycle.

Their belief systems also tell them that caregivers cannot be trusted or relied upon to understand them and meet their needs.

Affective displays

From the first days of life, children use affective displays, such as crying and smiling, to command the attention of their caregivers. Throughout childhood, children who have an attachment disorder continue to rely on affective displays to:

- assure attention to their needs

- punish and distance their caregivers

- release pent-up anxiety/arousal

Children who have an attachment disorder will often seek to communicate their thoughts, feelings and needs through their behaviour and affective displays, much like a preverbal child.

In addition to smiling and crying, children with attachment disorder may communicate their thoughts, feelings and needs by:

- sulking

- tantrums

- aggression

- destructiveness

- clinginess

- repetitive actions to secure attention (such as turning lights on and off)

As a result of neglectful care and associated mistrust of others, they often do not progress to the stage of articulating their thoughts, feelings, wishes and needs via language. They consider controlling, manipulative behaviours and affective displays to be a more effective strategy.

Colby Pearce is principal psychologist at Secure Start – a private psychology practice based in Adelaide, Australia. He is the author of A Short Introduction to Attachment and Attachment Disorder, Second Edition, published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Trending

Classroom strategies

SEND leader Kate Wells explains how best to deal with children with attachment disorder in your classroom…

Some schools still operate a ‘rewards and sanctions’ behaviour approach, where gaining praise and positive attention from adults are conditional on ‘good’ behaviour.

While this may work for some children, for many it can perpetuate their feelings of low self-worth and shame. This can lead to further negative behaviour and a cycle of conflict that can be hard to get out of.

Try to remember to validate feelings before facts. When a child is upset, frustrated or angry and acts in a negative way, it is easy to go straight to reprimanding the negative behaviour.

If you take time to understand the reason behind it, the child is more likely to feel listened to and you have a greater chance of then addressing and therefore altering the behaviour.

Children with attachment disorder often have feelings of low self-worth and shame. It is really important that as adults we do not further add to this with the language we use.

A child who already feels shame will expect an adult to be cross with them or rejecting of them. Ensuring that a child knows that it is the behaviour, not them, that is unacceptable is vital.

Reduce anxiety

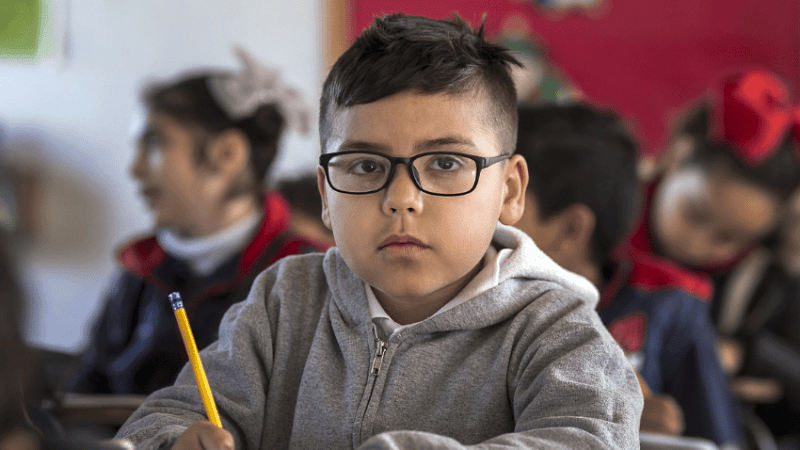

A busy classroom environment can cause anxiety for children with attachment difficulties. Think about the seating in your classroom. Children with attachment disorder often like to be able to see the teacher and scan the classroom easily.

They might prefer to be near a door or with their back to a wall. Unstructured time such as lunchtime can also cause anxiety.

It can be helpful to ensure these times are planned for. Visuals with explicit expectations of what they are expected to do, and what they can expect others to do, can help reduce anxiety.

Attention seeking

Children with attachment disorder may be heavily dependent on having your attention. They may present as clingy, ask seemingly trivial questions or ‘act out’ to get your attention.

Try noticing small things such as a new haircut. Get them to do an important job to help them feel connected to you. Frequently giving small amounts of attention can help alleviate anxiety that you’re going to forget them.

These techniques help build up children’s independence in a way they feel safe and still connected to you.

Quiet time

Build quiet time into your day so children can ‘catch up’ on processing. Having mindfulness activities or providing sensory and movement breaks can be helpful strategies to reduce tension.

Smooth transitions

Transitions can be particularly difficult for those with attachment disorder. This could range from going down the hall to assembly or having a different teacher for the day, to more significant changes such as trips away or moving schools.

Taking time to go through small changes will really help. Larger changes need longer planning, with opportunities for the child to gradually build up their confidence in a new area or with a new trusted adult.

Some secondary schools start transition work in Y6 with taster lessons and immersion weeks. It’s important your pupils know that change, and feeling anxious about it – is OK.

Visuals and social stories can help children become familiar with transitions and validate their feelings about changes.

Partnership working between home and school and within the school setting is imperative to the success of children with attachment disorder.

Having handovers between adults and involving children in plans will ensure better joined-up working and smoother transitions.

Kate Wells is deputy head at KnowleDGE Learning Centre and a local leader in education for SEND.