Curriculum and assessment review – Becky Francis review explained

The government’s sweeping review of the curriculum and assessment system is making waves – and rightly so, but what will the changes mean for teachers?

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

We look at what the government’s big curriculum and assessment review, including what’s being said so far, why it matters, and what changes might be coming…

Table of contents

What is the curriculum and assessment review?

What should teachers expect from the curriculum and assessment review? Teacher Toby Marshall investigates…

More than ten years have passed since the government last looked at the National Curriculum. The current Labour administration has initiated a curriculum and assessment review, headed up by Professor Becky Francis.

The government published an interim report in March 2025. This comprises an independent review of the current curriculum and assessment system in England, with statistical analysis.

Who is Professor Becky Francis?

Professor Becky Francis CBE is chief executive of the Education Endowment Foundation. She was previously director of the UCL Institute of Education. She has also held senior roles at King’s College London and the RSA. Francis has also been an advisor to the Parliamentary Education Select Committee.

At a recent education conference, Francis made clear that in her view, “Subject-specific knowledge remains the best investment we have to secure the education young people need in a world of rapid technological and social change”. The interim report reiterates this point.

What’s been said so far?

Evolution, not revolution

Early indications seem to suggest that the revised curriculum may entail more incremental changes than we’ve seen before.

I particularly welcome the proposed commitment to ‘Evolution, not revolution’, and the stated intention to maintain intellectual standards through a number of important qualifications.

As a film studies teacher, I think placing a greater emphasis on the arts would be a great idea. Study of the arts is, of course, academic – but it’s practical too.

‘Relevant’

At the same time, however, there’s talk of the curriculum and assessment review aiming to make the curriculum ‘more relevant’ to young people.

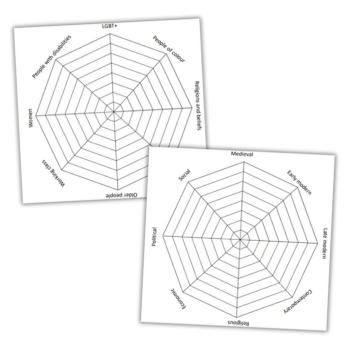

My concern is that the government could use ‘relevance’ as a criteria for narrowing the scope of our academic ambition for the young – especially when the very terms of reference state that the new curriculum should be “Inclusive, reflecting the issues and diversities of our society and ensuring that all young people are represented.”

Surely a key purpose of any school curriculum is to do precisely the opposite? It should introduce the next generation to people and places they haven’t previously encountered, and whose lives and experiences are radically different to their own.

History has shown that the National Curriculum is at its most effective when unencumbered by bureaucracy, and when the valuing of knowledge is placed front and centre. Let’s hope that the government agrees.

Toby Marshall is an A Level film studies teacher and member of the Academy of Ideas Education Forum.

What should the new curriculum contain?

This curriculum and assessment review gives the government an important opportunity to raise outcomes for children across England, argues primary headteacher Marc Hayes…

Why is a high-quality curriculum so important?

We can never be certain what our pupils’ futures will look like. But we can be absolutely sure that their ability to respond to the challenges they face will be based on the knowledge they acquire at school. .

For this knowledge to be secure, children need clear, structured curriculum sequences that focus on the critical content of each subject.

With strong foundations in this core knowledge, we can empower all our children to construct the deep, rich, and interconnected schema to which they are all entitled.

What’s wrong with the current curriculum?

Among the most common complaints about the national curriculum are that there are too many subjects, too much content, and not enough time to teach it all.

Debating the first two complaints will likely form an important part of the government’s curriculum and assessment review.

But whatever the form of the next national curriculum, schools will still face the challenges and limitations imposed by the length of the school day, weeks, terms, and years.

There is a stark irony that the national curriculum in England has too much content, despite most subjects’ programmes of study covering less than two sides of A4.

Whilst the lack of specificity has offered important opportunities for curriculum innovation, in many cases it has perpetuated the use of a topic-based approach to curriculum planning.

Children ‘do’ the Romans in history, or volcanoes in geography. But what they learn is not always easy to connect to existing schema. This reduces both the content’s relevance and its ability to stick.

When content struggles to be more than a list of facts related to a topic’s name, curriculum sequences can yield poor returns on the time and resources invested in teaching and learning.

Children can quickly become overloaded with seemingly disconnected information and, consequently, fail to commit the content to long-term memory.

Trending

What opportunities does a new curriculum present?

By pursuing Tim Oates’ initial aim of teaching “fewer things in greater depth” and using principles of cognitive science for curriculum design, we have a wonderful opportunity to refine the national curriculum and improve outcomes for all our children.

Reforming the national curriculum presents an opportunity to specify the key content and concepts that children should learn to make progress in each subject.

The vagueness of the current programmes of study can easily cause schools to overload their individual curriculums.

Although teachers widely consider spaced repetition a powerful pedagogical tool, it is difficult to put its potential into effect when teaching sequences – with all good intentions to deliver progress and ensure coverage – that continuously introduce new content.

Curriculum reform is an opportunity to identify which concepts are critical at specific points in children’s learning, and to suggest how teachers can revisit them in different contexts in each subject.

What about sequencing?

The sequencing of the curriculum also makes a huge difference to children’s learning. When we talk about conceptual development, we are describing how children’s schema grows over time.

Multiple examples of the same concept in different contexts, such as the water cycle in geography or nutrition in science, have the potential to grow deep and interconnected schemata when new learning is deliberately connected to prior understanding.

Reforming the curriculum to prioritise content linked to the essential concepts of each subject would provide teachers with increased clarity about what to teach.

Guidance on the examples to use and the order in which to introduce them would support pupils in making significant and ambitious progress.

Quality over quantity

Identifying the building blocks of each subject, and designing the roadmap from novice to expert, requires substantial subject knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge from curriculum designers. It requires an understanding of the content, its connections, and the way knowledge is constructed.

This poses an incredible – and often insurmountable – burden on teachers that is felt strongly across the sector.

While retaining some opportunity for curriculum innovation is important, so too is the need to collaborate with subject experts. This will mean any reforms to the national curriculum are evidence-informed. It will also ensure that specifications focus on the key concepts in each subject.

High-quality resources

The government also has an opportunity to support teachers by investing in high-quality curriculum materials to accompany the implementation of any reforms.

Non-statutory textbooks, crafted in consultation with both subject experts and teaching specialists (and with the principles of cognitive science in mind) could provide a minimum offering for pupils across the country, especially in schools that may lack the necessary tools or expertise.

Such a resource would save significant time across the sector, reducing teacher workload while enhancing teaching and learning.

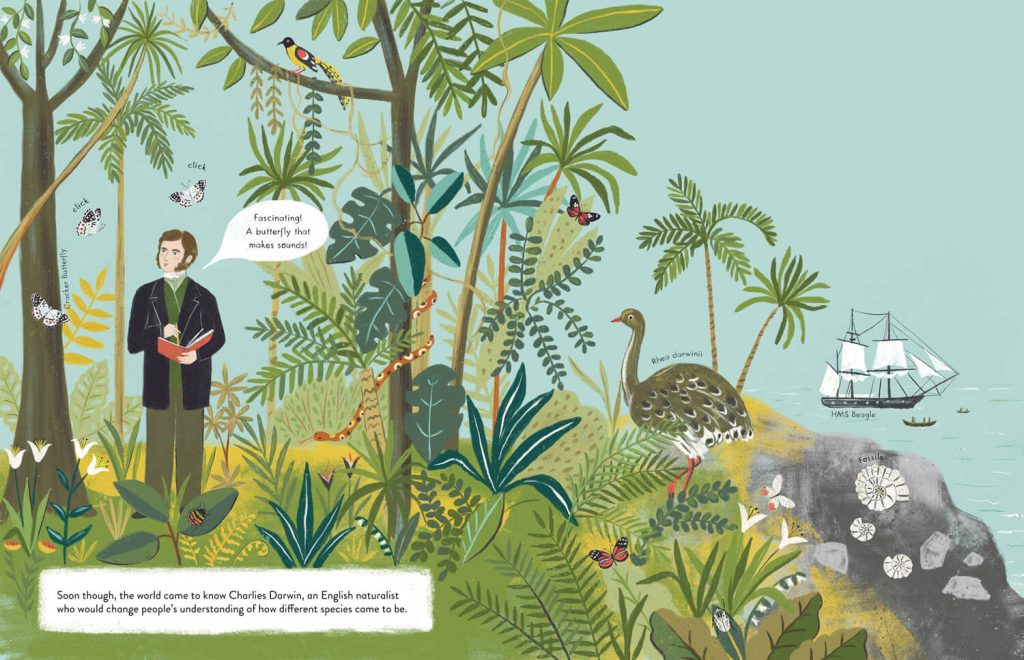

Another opportunity to support primary teachers in particular would be the commissioning of high-quality picture books to reinforce curriculum knowledge.

Dan Willingham speaks of the psychological privilege of stories. There is an increasing number of wonderful texts, such as Sabina Rodeva’s On the Origin of Species, which present complex information in accessible and appealing narratives.

Whilst this collection is growing, such resources can be difficult to source. They also do not always align with the programmes of study.

Specially commissioned texts, which harness the power of story and are directly linked to statutory outcomes, would be a gift not only for primary subject leaders and teachers, but for children across the country.

Marc Hayes is headteacher at Horsforth Newlaithes in Leeds. Follow him on X at @mrmarchayes.

Will children have a say?

The Youth Shadow Panel, a group of young people and youth organisations, is leading its own version of the government’s curriculum and assessment review.

The panel released its interim report in February 2025. This summarised its call for evidence and outlined young people’s thoughts on the education system.

Findings included the following:

- Overreliance on exams causes stress for many students

- Learning should be more relevant to life, more inclusive and more interactive/practical

- Climate, environment and nature education is lacking