Comics – How to use them in your classroom

Comics and graphic novels are a much more versatile teaching tool than you might think…

With homegrown comic artists like Jamie Smart flying off the booksellers’ shelves, it’s easy to see that comics and graphic novels, are experiencing a renaissance among readers in primary schools across the UK.

But how can schools harness this excitement for the greatest impact across their curriculum?

Something for everyone

As a starting point, get some comics into class and see what’s out there that interests your group. If you aren’t sure, ask the children. You are likely to have a budding comics fan in your class. They’ll be bursting to share the joy of their reading passion with you!

Comics are a brilliant way to support less engaged readers in developing a love of story and a confidence in independent reading.

Many children find the combination of word and image a satisfying way to access stories independently. However, we shouldn’t limit comics to the less engaged readers. They cover all genres and challenge levels, and should be available to form part of everyone’s reading diet – including teachers’!

With the launch of the government’s latest Reading Framework (July 2023), the importance of a reading for pleasure pedagogy has been placed firmly alongside phonics as a key part of a school’s reading provision.

Building a comics and graphic novel collection as part of your book stock is a great way to start making use of this fun and accessible format.

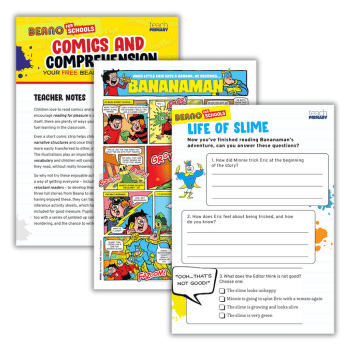

Weekly subscriptions to comics like The Phoenix and Beano are a great way to build excitement in the library or reading corner. They often present great value for money, as children pass them around the class again and again.

From great starter series like Mark Bradley’s Bumble and Snug or Ben Clanton’s Narwhal and Jelly (great for Year 2), right up to complex and heartfelt autobiography like Pedro Martin’s recent publication Mexikid, there is a wide range of titles out there to both entertain and challenge all levels of reader.

Say it loud!

Comics’ reliance on dialogue provides an ideal way to develop a group’s understanding of how you can use well-written dialogue to both develop character and move the action forward in a scene.

Take a look at some famous duos: Calvin and Hobbes, Tintin and Haddock or even Batman and Robin. If you looked only at their dialogue, would you be able to tell who was speaking? How has the author shown each character’s identity in their speech?

This line of questioning can stimulate some powerful discussions and help demystify what ‘good writers’ do.

Alternatively, flip this task and prepare a comics page with the speech balloons blanked out. Ask the group to complete the speech, thinking about both character and what’s happening in each panel. These tasks can be more challenging than you’d expect. They offer a great segue into developing the quality of dialogue in prose writing, too.

A space for silence

In recent years, wordless picture books have grown in use in the primary classroom. We shouldn’t underestimate the importance of developing appreciation of visual literacy and its role in reading and writing. The comic equivalent of a wordless picturebook, the silent comic offers another opportunity to explore the rich offering of visual narratives.

Silent comics can open a world of complex and subtle narratives to a much broader range of children.

Though easier to access, the level of discussion you can garner from visual texts has the potential to be in-depth and high-level. Without the barrier that written words can sometimes create, discussion can focus on the richness of the material, the intent of the creator, and character motivation.

For a starting point, take a look at works such as Gustavo Duarte’s Monsters, or Peter Van Den Ende’s stunning comic The Wanderer. Although they contrast in style, both these titles excel in silent storytelling.

If you’re interested in teaching art using silent comics, Little LICAF’s free downloadable planning for The Wanderer is a great place to start.

The sessions develop approaches to mark making inspired by Van Den Ende’s iconic black and white illustrative style. They build from there to produce a collective artwork based on the story.

Comics in the wider curriculum

Across the curriculum, graphic narratives can be a great tool for both acquiring and demonstrating knowledge. Various studies working with different age groups have shown that material presented in comic form boosts engagement and information retention. This is when compared to reading a standard text.

There are more and more non-fiction comic titles available to support use of the form across the foundation subjects. Titles like Emma Reynolds’ Drawn to Change the World and Mike Barfield and Jess Bradleys’ A Poo, A Gnu and You series are just two examples of using comics to convey complex non-fiction information in an accessible and memorable way.

Writing non-fiction comics in order to demonstrate subject knowledge is another way to challenge a class. Elements of history, science and geography all lend themselves to being depicted in a sequence of words and image.

You may be surprised by how details in the pictures demonstrate subject understanding. For example, children may pick up the wider historical context in the illustrations. Or they might demonstrate the concept of a sequence by displaying progression between panels.

These ideas are just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the possibilities for comics in the primary curriculum.

Comics are a form that covers all genres. They can be silly and anarchic, and deeply poetic. They can present complicated information in an accessible form, or themselves be incredibly complex to make sense of. This versatility and range offers huge potential for educators.

Just for fun

- Comics clubs and dedicated ‘writing for pleasure’ time, either in or outside of school, can provide a great opportunity to nurture reading for pleasure.

- Use comics as a hook to bring groups of children together to collaborate on a creative project. This offers a perfect opportunity to involve children who don’t see themselves as writers, or artists, in the process.

- Embrace children’s exploration of existing characters from their favourite books, games and TV shows. When writing for pleasure, they should have the opportunity to draw from the stories and pastimes they love, to create whatever they wish. There’s no need to start from scratch if they’re feeling overwhelmed by the idea. This freedom to reinvent characters or storylines from existing stories and put them together in inventive mashups is well used throughout the history of comics. It offers another way to break down the barriers that might put children off writing in their own time.

Lucy Starbuck Braidley is the producer and host of Comic Boom – The Comics in Education Podcast and is senior programme manager for Reading for Enjoyment at The National Literacy Trust.