Classroom behaviour – Why banning ‘fidget toys’ can do more harm than good

Debby Elley explains why classroom bans on fidget items can sometimes prevent students from making important progress

- by Debby Elley

You might be reading this article in the hope that it outlines some useful interventions you can use to help your students with SEND. There are times, however, when you can foster success simply by doing nothing.

Sounds like music to the ears, right? Nevertheless, there can be certain situations where students remain calm and focused due to the actions of teachers who simply know when to leave well alone.

Mental overload

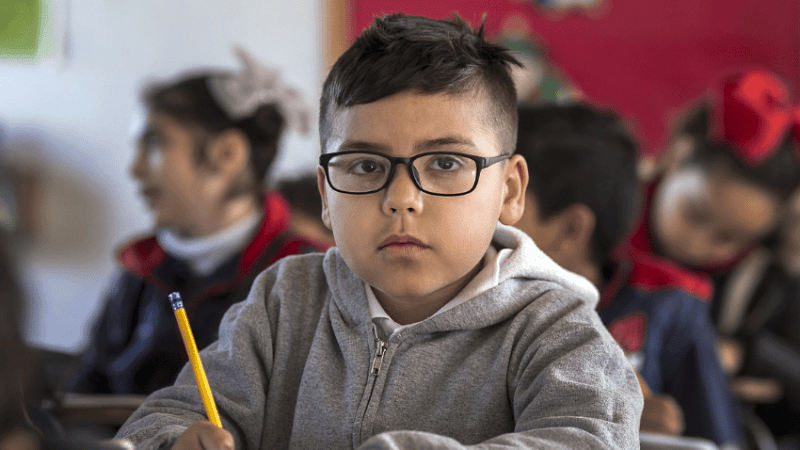

Take, for example, what we’ll call here the ‘habit’ of fiddling and twiddling with things. It’s a behaviour you may notice far more among autistic students, but please don’t assume it means they’re not properly listening to you. If anything, it’s more likely to be the opposite. Rather than distracting them from the lesson, some students’ fidget toys may in fact be the very coping mechanism that enables them to be attentive.

Autistic youngsters have highly reactive nervous systems. Their brains are constantly busy processing information that the rest of us can easily ignore as ‘background data’. Trying to then attend to auditory information at the same time is no walk in the park if you have autism.

The mental overload caused by trying to focus on a lone voice in a busy classroom can overspill into physical movement. How can you stay in your seat and continue to be polite whilst all this is happening to you? The answer is that you find something to fiddle with.

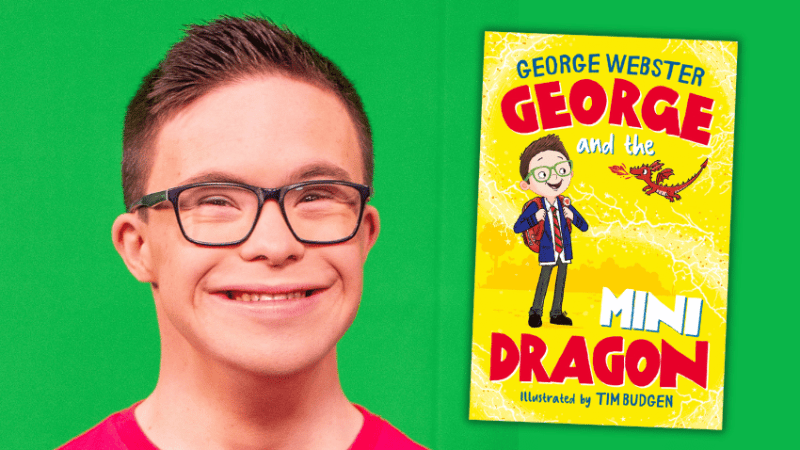

My autistic son Bobby, aged 18 and currently attending university, is now able to put into words the kind of insights he couldn’t express when he was in his early teens. “I’ve found that I can’t keep still, and need something to fiddle with,” he says. “My body is highly irritable sometimes, but having a fidget helps to calm me physically, so that I can focus mentally.

“Things like ‘simple dimples’ and fidget spinners can be really useful for work, because they can help you focus when you’re thinking about something. It matters that your hands are latched onto something when your brain is busy processing. It gives you a sense of calmness. It means you don’t have to rotate chairs or tap desks.”

Brain regulation

In specialist schools, where students can find focusing on tasks extremely difficult, occupational therapists will often timetable calming, physical activities ahead of lessons with heavy cognitive demands.

Robert Monk is an OT at the Seashell Trust – a school and college that supports students with profound and complex learning difficulties. He describes how, “Our team of sensory-integration trained OTs work with students to identify sensory strategies, which may include the use of fidget toys and/or twiddles. For some students, this tactile stimulation can help them concentrate and focus on a task.”

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that there will be students with similar sensory needs in mainstream settings. In mainstream schools, teenagers with sensory processing differences often end up having to find their own ways of regulating their busy brains, and a common one tends to be fidget toys.

Incidentally, this isn’t limited to just students with autism. Sensory Processing Disorder is usually part of autism, but stands distinct from it, and will often present in other conditions too. So how can you tell when someone is being genuinely inattentive, or merely fidgeting a little because it helps them to focus?

Personal context

The key to answering that is to understand the personal context – and it’s in these sorts of areas that Education, Health and Care Plans can often overlook crucial information. Getting it right depends on great SENCOs asking students and their families appropriate questions to ensure that any important coping mechanisms are included in their support plans.

What do you find calming when there’s a lot going on? What helps to focus you? Is there anything that’s worked for you in the past? If these self-regulation tools aren’t given attention, then things can, and often will go wrong.

“I get the impression that some teachers see it as more of a distraction,’ says Bobby. “I think it’s because when fidget spinners were popular around 2017, everyone started jumping on the bandwagon. But whereas they may be a distraction for others, they really aren’t for people with autism.”

Trending

A parent who shared her experiences with me and co-author Gareth Morewood for our book Championing Your Autistic Teen at Secondary School told us that her son used to take Blu Tack with him to primary school. She recalled how his fidgeting was occasionally used as a punishment – ‘You can’t have your Blu Tack until you do this piece of work!’ As she recalled, “All the ‘punishment’ did was make him cry, and the work never got done!”

As Gareth often likes to point out, we wouldn’t remove wheelchairs or hearing aids from students, yet we’ll often deny young people their own coping mechanisms through the unintended consequences of wider systems and policies.

I’m therefore hoping that as you read this article, you’re starting to wonder whether your school’s policies support the use of self-regulation tools or encourage a blanket ban on them. If it’s the latter, I’d venture that a rethink might be in order so that your setting can be inclusive, and adhere to that all-important need to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ for your SEND cohort.

Whilst fidget toys can help regulate busy brains, comfort items can be similarly important for reducing anxiety. In my last article for Teach Secondary, I wrote about how anxiety can quickly accumulate for people with autism, who will have difficulty in regulating their emotions when that happens. It’s what I call ‘the double whammy’, and it can lead to very obvious signs of overload.

Comfort items can form part of a raft of strategies to mitigate this risk. A typical comfort item might be a favourite possession from home. Sometimes it can just be an image. Bobby used to have a keyring with laminated photographs of his special interests that he could look at. The photographs would flood his brain with positive, soothing feelings, and drown out some of the ‘noise’ from his otherwise alien surroundings. Comfort items don’t always need to be on show – sometimes just knowing they’re available can make all the difference. Be led by the student.

What about the argument that allowing comfort items and fidget toys in class sets an unhelpful precedent? In my experience, concerns around whether peers will understand this ‘special treatment’ are generally raised by schools where leaders haven’t recognised the need for peer training to reinforce the policy exceptions that sometimes need to be made for students with SEND.

Difficulties will only arise when it hasn’t been explained that fidget toys are as important to some students as wheelchairs might be to others – and that no one would dream of banning wheelchairs on the grounds that they provide certain students with an unfair ‘advantage’ compared to their peers.

Collective solutions

If a fidget or comfort item is genuinely incompatible with the rest of the class being able to focus, enquire about what could be used as a less distracting alternative that performs the same job. The important thing is not to impose your own solution, but to work with families on finding one that suits all of you.

When considering all of this, I’d recommend you ponder one of my favourite quotes from the American poet, Robert Frost: ‘Don’t ever take a fence down until you know why it has been put up.’

When they feel secure, and in their own time, students will gradually reduce their reliance on fidget items. And if they don’t – so what? Inclusion doesn’t happen by making everyone else like us. It happens through accepting that some brains need different conditions in which to learn.

Debby Elley is the co-founder of AuKids magazine and a parent to twin sons, both with autism; Championing Your Autistic Teen at Secondary School, by Debby Elley with Gareth D. Morewood, is available now (£14.99, Jessica Kingsley Publishers). Browse more resources for Autism Acceptance Week, including our autism in girls checklist.