Trauma-informed approach – Supporting a care-experienced child

Taking a trauma-informed approach can create a truly nurturing environment for care-experienced pupils…

- by Stuart Guest

A trauma-informed approach at school means understanding that a child’s early life experiences can have a profound impact on how they view the world around them. This is particularly important for care-experienced children.

New data from the charity Adoption UK has found that almost two-thirds of adoptive parents (61%) say that finding a trauma-aware school would make the biggest positive difference to their family.

Trauma can manifest itself in many ways throughout our lives. However, early life experiences are usually about an event, or series of events, that have overloaded the child’s stress response system.

From birth, our brains are building connections based on our experiences. If, as infants, we are sung to and receive physical affection, our brain develops these connections. This is the world we expect and feel prepared for.

In contrast, a child who has experienced trauma will have built up connections in their brain in response to a world that feels unsafe and unpredictable.

To an infant, going without food, being left in their cot alone for long periods, or living in an environment filled with shouting and aggression can feel life-threatening.

These brain adaptations mean many care-experienced children are primed for danger. Feelings of stress and hypervigilence may remain, even when the child then moves into a safe and nurturing environment.

Encouragingly, trauma-informed practice has become more common in schools. Teacher Tapp reported recently that a third of teachers have now had some form of training. But that still means many have limited awareness, or experience.

As a headteacher, I’ve spent the past 12 years working with my staff to embed a trauma-informed approach in all we do. Most of our work is led by class teachers and support staff throughout the normal school day.

This means that even if your school hasn’t prioritised a trauma-informed approach, you can still apply the thinking within your own class. Here are some suggestions for getting started.

Build your understanding

Developing your own understanding about care-experienced children and the impact of trauma is essential. You may already have a child in your class who is adopted, or currently looked after. It’s useful to reflect on what you’ve learned from being their teacher. What has been rewarding? What has been more professionally challenging?

Care-experienced children often have low self-esteem and confidence, and they find it harder to self-regulate.

Things like turn-taking, sharing, or not shouting, can be areas where they need additional support. These children often require, and deserve, additional attention, support and consideration in our approaches.

Understanding more about the PACE approach can provide a useful lens through which to think about the needs of care-experienced children (see below). This was developed by psychologist Dr Dan Hughes

Understanding of early childhood trauma, and how it impacts children, is critically important if support for children who have suffered is to be effective.

I recently worked with BBC Teach to create a new teacher training resource, Supporting care-experienced children. This provides a good introduction. There are three videos covering some of the key topics, and three animations featuring the real-life experiences of care-experienced children.

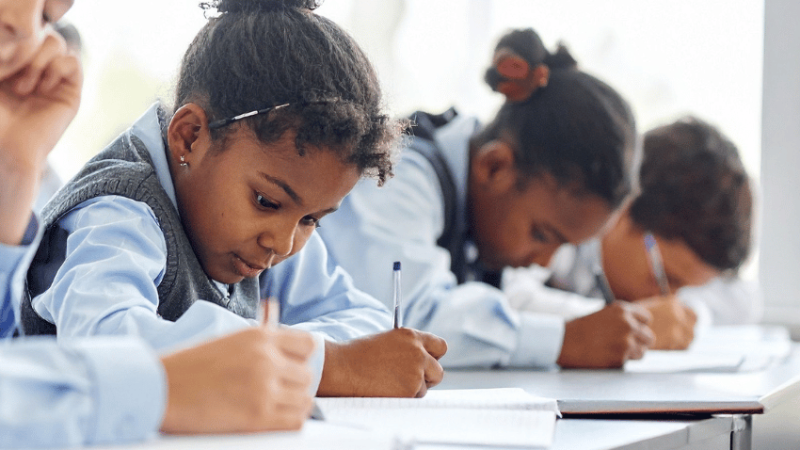

Classroom practice

Care-experienced children can feel shame deeply due to the trauma they have experienced. Something like sharing spelling scores with the whole class, or rewarding children who have good attendance, can trigger a strong shame response.

As teachers we want to praise children’s successes, but this must work for all pupils. Ask yourself, “What does this policy or approach feel like for my most vulnerable children?”

Behaviour charts, and other performance boards, are not helpful in supporting care-experienced children. They often have to work harder just to cope with day-to-day school life. Therefore it’s vital they are not disadvantaged further by policies that are in place.

It may feel daunting to adapt some of the tools you’ve relied on previously to manage your class. My advice is to try a more PACE-like approach. Even starting out with a curiosity sentence stem such as “I’m wondering if…” can make all the difference.

For example, if a child is struggling to focus in class, say to them, “I’ve noticed you are looking around the room a lot today. I’m wondering if you have something else on your mind right now?”. This approach can also help you to find out new information, which can make things better for the child (and you) in the class.

Of course, this doesn’t mean you get rid of rules, expectations and consequences. Boundaries and limits are just as important for care-experienced children as for their peers. For example, having strong routines develops a sense of safety for many children, as they know what will happen.

Consequences for actions need to focus on exploring the impact, building repair, providing support, and helping a child to develop the new skills they need. Ultimately, we want to reduce the likelihood of repeated incidents.

Changing your mindset

Care-experienced children are likely to live with far more stress than other children in your class. That can manifest itself in many ways, including how they behave in class.

Probably, one of the most powerful things you can do as a teacher is to stop thinking a child is being disruptive. Instead, see that a child is struggling. It may feel like they are being deliberately difficult, and a ‘real pain’. However, children rarely act up just for the sake of it; there is usually an underlying reason.

A trauma-informed approach asks:

- What is going on here? Why might this child be struggling now?

- What do I know about this child and their needs?

- What do we need to put in place to support this child and the situation?

Understanding things in advance about what might trigger a child can help you to put in place strategies that can support them.

A trauma-informed approach ensures a child feels supported and that they can rebuild trust in adults. A nurturing and stable environment allows a child who has endured early life trauma to learn how to develop healthy, dependable relationships.

Your classroom may well be the first place a care-experienced child has felt safe. Most importantly, as their teacher, you may be an important trusted adult – even if the child pushes your care away. By adopting a trauma-informed approach, and using PACE, you will be making a huge difference to their chances of success.

The PACE approach

- Playfulness – keep a warm tone and show joy in the classroom. This doesn’t mean having a joke when a serious incident has happened. Rather, it’s about having a day-to-day sense of enjoyment with the children. Take time to think about what your body language and approach communicate to the children, and adapt if necessary.

- Acceptance – acknowledge each child’s needs. Ensure they know you care and that they are a valued member of the class. Accepting the way a child is, and the challenges they may face, helps create a more considered and compassionate response and approach.

- Curiosity – aim to get into the cared-for child’s world and understand where they struggle. What is the trigger, or underlying need, that a behaviour is showing?

- Empathy – see things from the child’s perspective and don’t assume you understand the motives for their actions.

Stuart Guest is headteacher at Colebourne Primary School in the West Midlands. Access the BBC Teach free resource ‘Supporting care-experienced children’.