British values in schools – Everything you need to know

We break down British values in the classroom: the good, the bad, and how you can create champions of respect and tolerance…

- by Teachwire

What are British values in schools and how should you go about promoting them in your classroom? Join us as we unpack this complex topic and provide you with plenty of examples and ideas…

- What are British values in schools?

- What are the 5 British values in schools?

- How to promote British values in school

- Ofsted and British values

- Examples of embedding British values in your practice

- Case study: Sir John Sherbrooke Junior School, Nottingham

- More resources for teaching British values in schools

- How to model British values through leadership

- Criticisms of British values in schools

What are British values in schools?

In July 2014, the government announced that schools needed to ‘actively promote fundamental British values’. All schools need to have a clear strategy for embedding these values.

The introduction of this new requirement was not without criticism. Some people complained that the term ‘British values’ implied that these values were unique to Britain, implying that Britain was somehow better or more civilised than other countries.

Others worried that the government was asking them to promote stereotypical ideas of what it means to be British or to celebrate Britain’s imperial past.

The requirement to promote fundamental British values links with schools’ statutory duty to demonstrate “due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism”. We know this as the Prevent duty.

What are the 5 British values in schools?

Fundamental British values are defined as:

- Democracy – Understanding how democratic processes work and how the UK uses them to govern

- Individual liberty – Learning about rights, freedoms and responsibilities as individuals within a society

- Rule of law – Exploring the importance of laws in maintaining a safe and fair society, as well as students’ responsibilities within this framework

- Mutual respect/Tolerance of those with different faiths and beliefs – Fostering an environment of mutual respect and tolerance among students of different backgrounds, beliefs, and cultures. (Sometimes people view these as separate values, but they are closely linked.)

How to promote British values in school

Schools need to take care when promoting British values. It’s important to create safe spaces where pupils can discuss complex issues such as citizenship, equality and belonging.

We need to be able to support pupils to become critical thinkers, understand propaganda and persuasion techniques and develop the knowledge and skills to reject stereotypes, prejudice and hate.

Teaching British values in schools won’t entirely prevent radicalisation and extremism. However, it can help you to nurture critical thinkers and active citizens who respect others and challenge prejudice and discrimination.

The following areas of education are good places to embed British values teachings:

- School values and ethos

- English, history, geography, RE, citizenship, PSHE

- Assemblies

- Extra-curricular activities, visitors to school and school trips

- Classroom displays

- Communications with parents and carers

- Anti-bullying and equality initiatives

You may find it useful to appoint a member of SLT to lead on fundamental British values and SMSC and measure impact. This will ensure you embed provision throughout your school.

You have a statutory duty to publish your values and ethos on your website. However, you don’t need to publish a British values statement.

Instead, ensure you have an up-to-date values and ethos statement. Also link to examples of how you promote SMSC development, including promoting fundamental British values.

Ofsted and British values

The school inspection handbook states that in considering a school’s overall effectiveness, Ofsted inspectors must evaluate the effectiveness and impact of the provision for pupils’ spiritual, moral, social and cultural development.

This includes developing pupils’ “acceptance of and engagement with the fundamental British values”.

Examples of embedding British values in your practice

Democracy

- Participate in the UNICEF Rights Respecting School Award programme

- Invite young people to democratically elect a school council

- Ask parents and young people to complete a biannual questionnaire and use the comments to make improvements to the school

How do democracies work? Why do we need a free and enquiring press? Get some help exploring these big questions with this thought-provoking free KS2 democracy lesson plan from Matthew Lane.

Rule of law

- Reinforce the importance of school, class and country laws, as well as rules when dealing with behaviour

- Invite visitors from local police to reinforce young people’s understanding of the responsibilities held by various professions

- Create and reinforce golden rules, playground rules and safety rules within the school

Individual liberty

- Deliver e-safety and PSHE lessons

- Learn about human rights and explore what these mean for young people

- Teach the importance of speaking up about problems and sharing them with a trusted adult

Mutual respect/tolerance

- Join in with Anti-Bullying Week and teach children to value differences in others and themselves and to respect others

- Ensure your behaviour policy is consistent and that young people take responsibility to resolve conflict and repair relationships

- Celebrate events such as Black History Month, LGBT History Month, Disability History Month and Refugee Week

Explore how respect is about how we show our values and learn that it can be shown in a variety of ways, both to people and to the things they value, via this free sports-themed KS2 lesson plan.

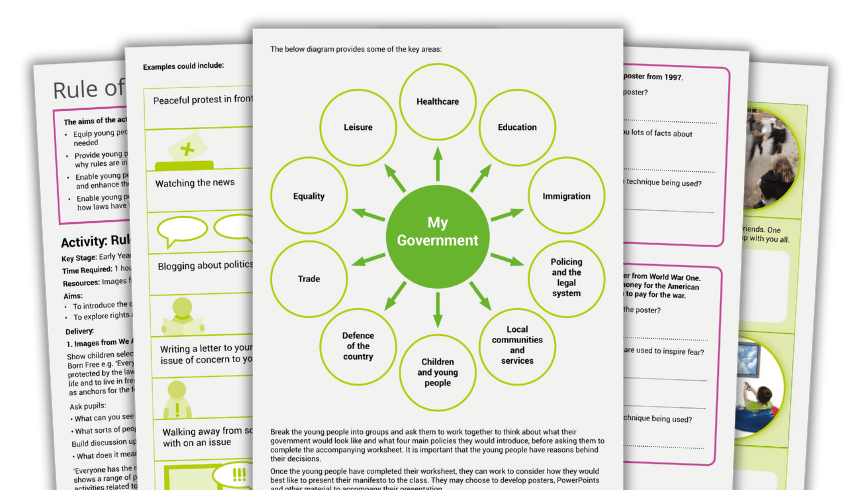

Find lots more ideas for each value in this free downloadable Universal Values booklet.

Case study: Sir John Sherbrooke Junior School, Nottingham

Engaging children with parliamentary process and democracy means teaching British values becomes more than just an exercise in ticking boxes, explains deputy headteacher Sally Maddison…

Walking past Y4 Oak class, the shouts of “Order! Order!” fill the air. No, it’s not a new behaviour management strategy; it’s a whole-class House of Commons-style debate.

The importance of ‘British values’ is one of those vague things we’re told to make a key part of our school life. However, it often ends up as a forced, faded display in some dusty corner of a school corridor. It’s something referred to every so often without fully understanding how to make it totally relevant for the children, especially when it comes to democracy.

I knew there must be a better way to approach teaching democracy – not just when we study ancient Greece. I discovered that by making a few small changes, teaching British values could (and did) become a massively valuable, engaging and enjoyable part of our school life.

As a school, our first step was to turn the school council into our school pupil parliament. This is a simple thing which had a huge impact.

Put it to the vote

Each class has their own MP. They represent their class’s views in meetings and then feed back the outcomes to the children.

To become an MP, the candidates campaign, create a list of ideas and promises – their manifestos – and deliver a ‘why you should vote for me’ speech.

The pupils then fill out individual ballots and vote in secret. We also vote for a school prime minister, from Y6, and they act as the head boy or girl.

The school MPs and PM meet regularly with a member of SLT to discuss their class’s ideas, feedback on previous ‘actions’ discussed, vote on new ideas and even set up in-school petitions for things such as ‘Music on the playground at lunchtime’. Minutes are taken at these meetings and displayed in each classroom.

By explicitly linking what the children are doing to how our actual voting system and parliament work has meant there is a much deeper understanding of elections and why it’s important to vote.

This isn’t too different from the way schools already elect school council representatives, prefects or head boys and girls. But by making these small changes, the children can really articulate what democracy means, why it’s important and use words like ‘campaign’, ‘manifesto’, ‘ballot’ and ‘representative’ in an informed way.

Finding time

Now, having a pupil parliament is all well and good, but how do we make democracy part of our normal curriculum when our timetables are already bursting at the seams?

Well, it so happened that our reciprocal reading text was the UK parliament primary schools booklet (it’s free from their website so I’d ordered a class set) and the children wanted to know what the word ‘debate’ meant.

This led to a discussion about how the MPs in the House of Commons debate and the kind of things they talk about. I mentioned that one recent debate had been about the sugar tax and suddenly the whole room was filled with shouts of, “It’s not fair,” and, “But I love fizzy pop.” So, the afternoon’s science lesson went out of the window and we held a proper, parliament-style debate.

I was blown away by the children’s enthusiasm, maturity and the wide range of different arguments they came up with.

Meaningful debate

First, the children had to research and think about the pros and cons for each side of the argument. Next, I separated them into two groups – the party in power who were for the sugar tax, and the opposition party who were against.

They were given roles, such as leader, deputy leader and minister for business, and then they sat in rows of chairs facing each other as they do in the House of Commons.

I played the role of the speaker of the house and the children had to stand up if they wished to say something. I referred to each child as ‘the right honourable’ and they were allowed to clap if they agreed with someone’s point, but no booing!

Trending

The results were incredible. These children, who often find it hard to listen, talk in groups effectively and offer detailed reasons in their comprehension answers, were being respectful, thinking about what had been said and giving informed and thought-through responses. Some even went home and watched real parliamentary debates.

By giving the debate a very clear structure, making them stand, not put their hands up and framing it all in the style of the House of Commons, the children were utterly engaged and left with a new understanding of democracy.

We did catch up on that missed science lesson, but more importantly, I’d learnt the power of teaching democracy. Debates like this now form part of our English programme of study, developing the children’s reasoning and oracy skills, as well as their understanding of the democratic process.

In fact, we’re currently setting up a Nottingham Junior Parliament to bring primary children together from different schools across the county and take part in House of Commons-style debates.

Direct engagement

I also discovered that not only can you invite your local MP into school, but you can also request a free visit from a member of the House of Lords. We’ve had two peers in school so far and both times the children have been enthralled.

And did you know that anyone can set up a formal petition to government that can be debated in the House of Commons? As soon as we learned about this, the children and I went on to the parliament petitions website and set one up.

A girl suggested we petition to get more help for children in school with type 1 diabetes, so that’s what we did. Now the children check the petition to see how many votes it has, look at the map to see where people have voted and even try to think up ways to get more votes.

UK Parliament Week

We’ve also taken part in UK Parliament Week, had free workshops in school from the parliament education team and after discovering that you can take school groups around the Houses of Parliament for free (with travel cost subsidies), we’ve also booked for 30 children to visit.

When I first thought about teaching children about the British value of ‘democracy’, I saw it as a one-off lesson to tick a box, but very quickly it became clear that it could become something that not only engages the children in learning about it, but also impacts other areas of their academic and social education.

- Create a school pupil parliament, giving the children the opportunity to campaign and vote.

- Hold House of Commons-style debates about topics that are relevant to the children, such as the start of the school day.

- Invite your local MP or peer into school to talk with and work alongside the children. All their details and email addresses are on the parliament website.

- Visit the Houses of Parliament for free by filling out an application on the education section of their website. Don’t forget to apply for the travel subsidy too.

- Take part in UK Parliament Week. They will send you lots of free resources and you can join in with their live lessons.

Sally Maddison is deputy head of Sir John Sherbrooke Junior School, Nottingham, an SLE and a Shakespeare ambassador for primary schools.

More resources for teaching British values in schools

- Explore the human rights of sexual and gender minority groups

- Right Here, Right Now: Teaching Citizenship Through Human Rights

- Young Citizens resources and lessons suitable for primary school children, exploring political and economic issues

- Games, resources and lesson plans from UK Parliament on democracy, government and voting for Key Stages 2 and 5

- Snopes – an internet reference source for urban legends, folklore, myths, rumours and misinformation

- The National Archives: Bound for Britain – Experiences of Immigration to the UK

- UK Youth Parliament – this provides opportunities for 11-18 year olds to use their voice in a creative way to bring about social change

How to model British values through leadership

James Hempsall OBE explains how you can create the right culture in your school to promote fundamental British ideals through management…

Fundamental British values are things we should constantly model through our leadership and management. The benefits of getting the culture right in your leadership behaviours will permeate throughout your staff team and result in them being integrated and effective within all aspects, including your curriculum.

Values in practice

Democracy

Democracy is all about making decisions together and this helps teams to develop self-confidence and self-awareness. Teams will always be more motivated when involved in the development of ideas and in reaching collaborative decisions that affect them.

Confident leaders and managers let go more than unconfident ones, and this process helps people to work together too. It also allows team members the chance to situate themselves in the organisation, and understand their views are important and valued.

The rule of law

The rule of law is all about understanding codes of practice, being accountable to them and following them. Within this context, it means following policies and procedures, employment law, health and safety and the curriculum.

By being the guardian of the rules of law you demonstrate that your behaviour, and that of everyone else, should be within professional boundaries, and there are consequences if this is not adhered to. This is a massively important principle for safeguarding and child protection.

Individual liberty

Individual liberty allows you and team members to be positive about themselves. Valuing difference, and acknowledging success and everyone’s qualities and contributions is vital. Be the super-praising leader your organisation needs you to be.

The result will be a team that has self-knowledge, -awareness and -esteem. Who knows what your confident team could go on to achieve next? And what a difference it will make to the children in their care. Such feelings are transformational and totally infectious – you’ll see!

Mutual respect

With that positivity comes the ability of you and colleagues to offer mutual respect. Treating others as you would want to be treated yourself. The watchwords here are inclusivity and tolerance, difference and diversity, and reflecting and valuing.

Now, doesn’t that sound like a truly sensible way of using British values to lead and equip your team? This way you can all develop the skills needed to work with children and families so they understand them too.

James Hempsall OBE is director of Hempsall’s training, research and consultancy.

Criticisms of British values in schools

Why ‘British values’ don’t belong in the classroom

A Level film studies teacher Toby Marshall sets out why he thinks education is not the place for propaganda…

The government has, for many years, instructed teachers to promote the ‘British values’ of tolerance, democracy, rule of law and individual liberty. There’s nothing objectionable about those values, but it’s hardly the job of teachers to ‘promote’ them.

For the most part, our job is to educate young people about values, and where time allows, introduce them to those principles by which moral and political decisions might be made. This is best accomplished through basic introductory classes in moral and political philosophy.

Uncritical promotion of any value proposition, whether presented by government or activists, within education is merely an invitation to propagandise. And education is not the place for propaganda.

There needs to be an acceptance, however, that teachers, like any other professional grouping, will include some individuals who get things wrong, for both good and bad reasons. Nobody here is pure. We’re all capable of indoctrinating students inadvertently, even when acting with the best of intentions, and our own acts of indoctrination will always remain invisible to ourselves.

At the same time, we have to bear in mind that indoctrination is miseducation. Any perception that teachers are deliberately miseducating students serves to drain the profession of trust among both parents and wider society.

Intellectual care

If teachers, or indeed the Conservative Party, were to use education for political purposes, it would be a gross abuse of power.

Parents send their children to schools and colleges for an education, not a sermon. For those parents who wish to outsource the moral education of their child, there are ample mosques, temples, churches and synagogues.

However, we should also remember that we live in a democracy. It’s quite right that teachers prepare young people for their future roles as citizens and educate them about politics. They should possess knowledge of the mature, albeit somewhat ramshackle and constitutionally contradictory democracy that they will inherit.

Alongside that, we should be clear that when teachers or the State seek to manipulate young minds and persuade them of the ‘truth’ contained within a particular religious, moral or political perspective, they cross a line. We have a duty of intellectual care.

Definitions of indoctrination vary, of course. For some, it will stem from a teacher’s intent; for others, it can be found in a curriculum’s content selection, or how that material is presented. What ultimately unites them is the sense of adults somewhere abusing their power in order to secure political, moral or religious objectives unrelated to education.