British history – Why schools should teach students about hidden and marginalised figures

The past and present are full of inspiring, yet sidelined individuals and groups, writes Shalina Patel – but schools can play an important part in giving them their dues…

You won’t know this about me, but I’ve got a tattoo on my ankle of some flowers, symbolising the bouquets suffragettes would be presented with when they were released from prison for the first time. In short, I’m a suffragette nerd.

So imagine my surprise a few years ago when I learnt there was a prominent suffragette who was not only Indian, but descended from Mughal royalty.

Discovering the existence of Sophia Duleep Singh – someone who looked like me, in a space that I’d always just assumed was white – impacted me significantly.

It also begged the question, who else has been hidden from British history?

What hidden historical figures often have in common is that they will have been marginalised. They will typically be people whose class, gender, sexual orientation, race or disability resulted in them being excluded from the mainstream historical narrative.

‘T’ is for ‘tokenistic’

Intersectionality plays a role here. Embedding diversity, as opposed to simply paying it lip service, isn’t about ‘bolting on’ and running the odd standalone lesson. It requires creating space for these stories to be told – frequently within contexts you probably teach already.

Consider, for example, how textbooks will often frame non-white presence in Britain as starting with the Windrush generation. Instead, try acknowledging the existence of Indian ayahs in Britain from the late 1800s, or the key roles performed by an indentured Chinese workforce during WWI.

Into your Tudor England lessons could be woven the story of black trumpeter John Blanke, who received a wedding gift from Henry VIII.

Many KS3 textbooks concerned with the post-Windrush era tend to frame race relations within an American context.

I doubt that any students will finish KS3 History without knowing who Rosa Parks is, but why not compare her activism to the actions of those involved in the Bristol Bus Boycott of 1963 who were directly inspired by her example?

‘C’ is for change

I’ve seen students embrace this approach. Just as they respond with a resounding ‘Woah!’ when you tell them no one has successfully invaded England since William the Conqueror, their reaction upon hearing about the Ivory Bangle lady is one of excitement.

I’ve seen colleagues react similarly when I’ve delivered a Y9 lesson on Noor Inayat Khan (an undercover agent during WWII who was executed by the Nazis – see main image) to all staff as part of our CPD programme.

Surreal and terrifying though it was to see the usual occupants of my classroom replaced by teaching staff, it was a great way of highlighting directly to teachers just how rewarding sharing such stories can be.

Since that experience, I’ve seen encouraging changes. In English, The Colour Purple replaced The Help, after some reflection within the department that a text centring marginalised voices would provide a truer narrative of race relations during the period.

I was also forwarded a number of student science presentations around ‘inspirational scientists’, one of which focused on a student’s grandfather – a Yugoslavian doctor who worked in a refugee camp during the Bosnian war. You could feel the student’s pride beaming through the screen.

Watching some of my Y11 form perform scenes from Queens of Sheba – a play that viscerally exposes the misogynoir experienced by today’s young black, British women – for their drama GCSE was a powerful and unforgettable experience.

Of course, there’s always more work yet to be done; this is an ongoing process that will see us continue to reflect, improve and scrap as necessary. I don’t believe we’ll ever even ‘finish’ this journey – but acknowledging our need to change is key.

At first glance, it’s ‘easier’ to make curriculum changes like this in history than it is in, say, maths or science. But what about the original pioneers behind various far-reaching theories, or those innovating within different scientific and mathematical fields today?

Witness the ‘Rocket Women’ – sari-clad scientists working at the Indian Space Research Organisation, who played a key role in developing India’s Mars Orbiter mission, Mangalyaan.

The photo of them went viral in 2014 for the way it disrupted the domestic sphere that women like this are so often associated with.

‘D’ is for ‘decolonisation’

Back in June, a BBC news crew came to interview me and my students on the importance of teaching a diverse curriculum.

One area highlighted in the report was the steps we and others are taking to not start teaching black history with slavery, but to also cover the existence of thriving African kingdoms beforehand.

Without providing this context, we surely risk perpetuating the Victorian view of Africa as the ‘dark continent’.

I’ve been a teacher for over a decade and never experienced this level of public interest in the school curriculum before. The term ‘decolonising the curriculum’ has been floating around within academic circles for a while now, but now it’s newsworthy, as seen in the recent debates over statues of historical figures associated with slavery, and the profound questions now being asked of the legacy left by Britain’s slave trade.

I’ve recently led some training through Challenge Partners on what exactly this means for schools, and the questions we need to be asking ourselves in order to reflect on and improve the experience we offer our students.

So, how should you go about decolonising and embracing intersectionality, without being tokenistic?

‘A’ is for action

First, review your curriculum as a department and reflect on it honestly. At KS3, look for opportunities to share space and shed light on overlooked people, places and events within your existing offer.

This is trickier at KS4/5, of course – but where there’s room for independent choice, consider which approaches might widen the perspectives of your students the most.

Are the choices you’re currently making based only on what you’ve always taught? Irrespective of the subject you teach, there will always be areas within your curriculum where room can be made for new voices.

We all regularly scrutinise our students’ work, but what about our teaching resources? There’s a good chance that some of the materials you use will be outdated and/or problematic in some way.

Where appropriate, report any concerns to the relevant publisher, and keep said materials out of students’ reach.

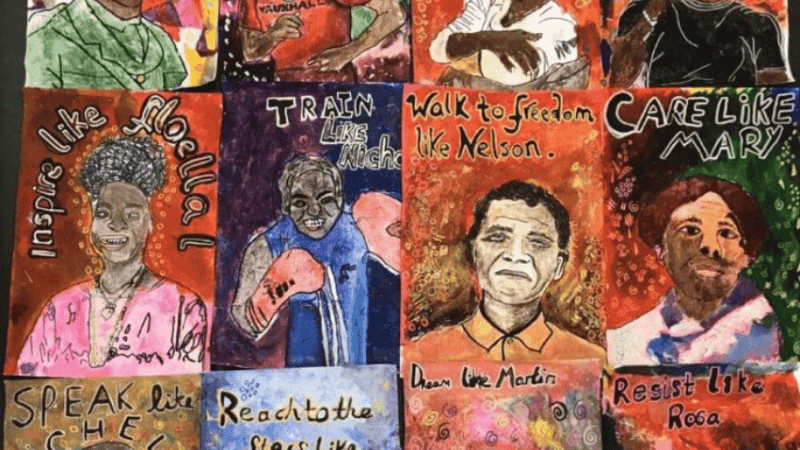

And while we’re at it, put down that PowerPoint presentation filled with Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr quotes. Your students will have seen the same life stories being celebrated year after year since the start of their formal education.

Assembly and registration times are great opportunities for surprising your students – why not use them to introduce some new faces, contexts and perspectives?

As you survey your classroom and walk the school corridors, think about who is being celebrated and how.

Are students seeing displays of work that were originally marked five years ago and are now fading fast? Or are they seeing inspirational people; innovators in their respective fields and vivid examples of emerging careers relating to your subject?

As well as being an ongoing process, reviews of this sort need to be whole school efforts. Put together a working group, make it cross-curricular and create short, medium- and long-term plans.

Reflect on what you’ve done in the past, what’s happening now (because there are always great things happening) and how you can build on these. It’s a process that needs to be taken on by everyone, at all levels – not just your history department…

Shalina Patel is a history teacher and head of teaching and learning at Claremont High School, North West London.