Behaviour management strategies – Expert ideas for secondary

Start September with behaviour standards high and carry them on throughout the year with some of the best advice for KS3 and KS4…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

We’ve tailored these expert behaviour management strategies to the specific needs of secondary teachers. They’ll help you create a conducive learning environment for students while navigating the unique challenges of teenage years…

(We’ve also got behaviour management strategies for early years and primary).

- Bitesize behaviour management strategy tips

- Negotiating the balance between compassion and discipline

- Why students do better when we empower them

- Post-Covid behaviour management strategies for teenagers

- What research says about rewards systems as a behaviour management strategy

- Take control of behaviour in just 15 seconds

- How to use group psychology to influence behaviour

- Behaviour management strategies checklist for the new term

Bitesize behaviour management strategy tips

Do no harm

The first principle of your behaviour management strategy should be ‘Don’t make things worse.’

You might feel hurt by that boy’s personal comment, irritated by those giggly girls’ whispers, wound up that pair’s continual chatting. But losing your rag with the class, whether you think it’s justified or not (which, by the way, it’s not) won’t help.

Instead, wait until you’ve calmed down before you act. You’ll be more balanced, objective and reasonable, in a way that will benefit both you and the student(s). Oh, and you’ll have modelled a really useful life skill in the process – namely self-control.

Don’t let the apparent simplicity of this behaviour management strategy give you the impression that it’s not important, because it is. Very. And be wary of labelling it as ‘obvious’.

“Wait until you’ve calmed down before you act”

The problem with describing certain things as obvious is that, well, it’s not always the case that they are – at least not to everyone. The same applies to ‘common sense’. This can sometimes turn out to be not as commonly understood as we think it is.

To reiterate, ‘do no harm’ should be the first principle of your behaviour management strategy. And you do no harm by carefully controlling your reactions to any and all behaviour situations you find yourself in.

Revisit your rules

When it comes to behaviour management strategies, revisit your school rules frequently. It doesn’t matter if student behaviour is currently good – you must still revisit your rules.

In fact, this might actually be the best time to revisit your rules. Why? Because the students will be receptive, rather than defensive, hence the experience will be positive rather than negative. And because being proactive is better than being reactive.

How you revisit your rules is up to you. Just do so often, and in different ways (repetition and variation being key to embedding information in long term memory).

A simple yet powerful way of revisiting your rules can be to draw attention to them when pupils are following them. Here’s one example…

“Three, two, one…pens down. Thank you. And thank you for following rule 2, ‘We follow instructions right away’…”

And another…

“I liked the way you said ‘please’ and ‘thank you’. Politeness fits squarely with rule 4, ‘We respect each other’. Good.”

Counting down from three behaviour management strategy

The ‘count down from 3’ behaviour management strategy is a good way of getting a class’ attention following paired or group activities.

Count down from three slowly, clearly and with some ‘oomph’. Don’t draw out the vowel sounds (so not ‘threeeee’ but ‘thre/’). This clipped approach makes the numbers stand out and communicates to the students that they need to quickly finish whatever it is they’re doing.

Leave one or two seconds between numbers to let them do just that. When you get to one, the whole class should be giving you their silent attention.

If you get to one and a student is still talking, look at the student with a neutral expression until the talking stops. Hold that look for a further moment or two, then crisply begin the next part of the lesson.

If the student talks over you again, initiate a private intervention by talking to them beyond the earshot of their peers. Be clear about your expectation for silence – ‘We are silent when the teacher is talking.’ If the student talks over you again, impose a consequence.

“If you get to one and a student is still talking, look at the student with a neutral expression until the talking stops”

This behaviour management strategy is respectful, efficient and when done right, highly effective. It allows for crisp transitions between activities, so that you don’t waste time or lose your lesson’s momentum.

Always respond

Always respond to misbehaviour. Don’t turn a blind eye, look the other way or pretend you didn’t see something when you did. You have to address and challenge misbehaviour with an effective behaviour management strategy.

A key reason for teachers failing to address misbehaviour is that they doubt their ability to effectively deal with it. There’s the niggling doubt that doing so will somehow backfire on them, so that what stops them is ultimately fear.

Trust me, you have the capacity to be excellent at behaviour management strategies. You genuinely do. Even if you think you don’t, when faced with student misbehaviour, your only option is to address it. Sorry, but it’s true.

But here’s the good news. So long as you don’t shout, or say anything unkind, then whatever you do will be better than doing nothing. If an intervention doesn’t go as well as it could, you can still learn from that for next time.

“When faced with student misbehaviour, your only option is to address it”

If you felt a degree of fear (or even a lot) while responding, know that next time that fear will be lessened. Bravery begets bravery. Similarly, fear begets fear. So, deep breath – find your voice and say something.

Directed praise behaviour management strategy

If a student is misbehaving, praise nearby students for demonstrating the kind of behaviour you want to see.

When doing this behaviour management strategy, be specific: ‘Billy, you’re really focusing on what you’re doing. And you, Janet. Your pen hasn’t stopped writing.’

The misbehaving student will almost certainly want to receive some of that praise too, and thus change his or her behaviour in order to get that praise.

When that positive change happens, however, make sure that you’re not too quick to acknowledge it. Wait a while. Scan the class. Attend to another student.

Then – and only then – go back to the original student and acknowledge that their behaviour has now improved. A slight nod or a mouthed ‘good’ is normally sufficient.

Why not lavish praise as soon as you see that change take place? Because you want the student to be working hard to get that praise. Give too much praise too quickly, and you’ll only cheapen it.

No chatting

Teachers often ask me how much chatting is acceptable in class. The answer is simple – none.

Work-related talking is another matter, since that’s an explicitly sanctioned learning approach used for certain activities. But don’t allow casual chats. Why? Because ‘No chatting’ is a legitimate boundary. It’s a clear boundary, and an enforceable boundary.

“Give too much praise too quickly, and you’ll only cheapen it”

You are in the classroom to teach. Your students are in the classroom to learn. Chatting gets in the way of both, so not allowing it is a legitimate boundary. And it quickly becomes clear when that boundary has been broken.

If you’re a teacher who believes a little bit of chatting is okay, ask yourself – when does ‘a little’ chatting become too much? Where’s the line, and how will students know when they’ve crossed it?

If that boundary is left vague, students will likely get away with chatting until the teacher’s had enough – at which point, the teacher shushes them.

Thanks to that vague boundary, though, the silence won’t last long – resulting in further chatter, more shushing, and repeat. It’s a tedious pattern that’s easily avoided if the classroom expectation is that of ‘no chatting’.

Closed choice behaviour management strategy

When it comes to dealing with misbehaviour, you may well find it useful to present students with a closed choice.

That is, a choice where one of the options you give them is plainly going to result in a more favourable outcome all round, compared to the other:

“Chloe, do you want to do the maths questions now, or during break?”

“Faisal, would you like to help Peter tidy the work area now, or would you like to do it at the end of the lesson on your own?”

If Chloe chooses not to do the maths questions now or if Faisal chooses not to help Peter tidy the work area, then you must duly go ahead with enacting the less favourable option. This is even if the outcome is ultimately less favourable for you as well. (Spending the break with Chloe, for example.)

Closed choice is a behaviour management strategy that definitely works – but only if you actually mean what you say and follow through on the consequences.

Be unfailingly consistent

Make sure that you’re consistently the same person in each lesson, day in, day out.

There should be no surprises, erratic behaviour or sudden character shifts. Needless to say, the person you need to be is decent, measured and boundaried.

Be the same person with all of your students. You have no favourites in your classroom, or if you prefer, every student is your favourite. Either way, all should feel equally valued.

“There should be no surprises, erratic behaviour or sudden character shifts”

The stuff that’s happening in your life? Money worries, relationships, work issues – whatever it is, it shouldn’t intrude in your classroom, influence your behaviour or unsettle your consistency. Whatever’s outside the classroom must stay there.

By being consistent, your students will know where they are with you. They’ll understand your expectations and be able to work towards them. They’ll understand your boundaries and be able to keep within them.

But if you’re inconsistent, none of that’s possible. You’ll become a barrier to the learning, end up losing your students’ respect or worse – fill your students with anxiety as they try to double guess what you’re going to do next.

Depersonalise it

Never allow yourself to feel hurt, angry, let down, dismayed, betrayed or disappointed by anything a student does, or fails to do.

Remember that the student is a child. Maybe a young child, or perhaps an older teenager, but a child either way. They’re still under development, still a work in progress. They’re, well – still very much in the process of growing up.

So don’t take it personally – especially if what the student has said or done was meant to be taken personally. All that reflects is their level of maturity. That’s it.

Even if you do feel genuinely hurt, angry or troubled as a direct conseqeunce of something a student has either done or failed to do, don’t let it influence you. Consume those emotions. Keep them firmly to yourself. Put a lid on your feelings.

By all means, give yourself some brief thinking time if you feel you need it. A little cognitive breathing space might be helpful, but whatever you do, don’t react in a personal manner to the student’s actions. Because if you do, you’ll almost certainly make the situation worse.

Transform your classroom transitions

As every teacher knows, periods of transition have the potential to trash your lesson.

All that lovely calm and focus can go in an instant, replaced by students wanting to chat to their mates, swing on their chairs, check their phones – the list goes on.

Even in the absence of any misbehaviour, transitions are still dead time. The longer they take, the less time there is for teaching and learning.

It follows that transitions deserve special attention. In fact, the trick with transitions is to view them as activities in their own right.

We wouldn’t let students perform an activity without some planning on our part – likewise, we should pre-plan our transitions. At the very least, do this:

- End the previous activity crisply, and instantly start the transition

- Have your own resources organised and ready to use

- Have the students’ resources organised and ready to use

- Hand out resources when students are engaged in work – they’re not to be touched until you say so

- Issue instructions clearly and succinctly (rehearse them beforehand)

- Teach routines for giving out and collecting in work, items of equipment, etc.

- Begin the next part of the lesson promptly

By viewing transitions as activities in their own right, you can rid your classes of dead time for good.

Describe ASAP

Describing exactly what the student is doing is often more effective than instructing him or her to do something.

For example, rather than telling Lynda to be quiet or Dan to sit in his chair, say “Lynda, you are talking” or “Dan, you’re standing up.” Keep your tone neutral.

You’re not reprimanding with this behaviour management strategy, but simply bringing the situation to the student’s attention. Don’t add phrases like ‘again’ or ‘ as always’.

The power of ‘describe’ is that it sidesteps much (though not necessarily all) confrontation. You’re just stating a fact as you see it. Now it’s up to the student to change his or her behaviour. If they don’t, up the strength of the intervention.

Make sure you describe the misbehaviour as soon as possible (hence the ‘ASAP’). This will not only add extra oomph to your intervention, but also communicate something very important about you – that you’re on top of student behaviour.

Don’t let the apparent simplicity of this behaviour management strategy make you think that it’s not effective, because it is – very.

Not so long ago, I was visiting a school when a teacher – who had previously attended one of my behaviour management training sessions – approached me to say that ‘describe’ had remained her default behaviour management strategy.

When I asked her why, she said, “Simple – it works.” So there you are.

Orderly endings

We’ve all experienced rushed lesson endings. Perhaps we let an activity overrun, or went off on a tangent, but they’re best avoided.

Rushed equates to disorderly, and ‘disorderly’ isn’t a trait you want your students to associate you with. Far better to be orderly – organised and in control.

When rushed, you’re also more likely to miss something important, like explaining the lesson’s homework or issuing important reminders. Students may additionally leave your lesson a bit ‘hyper’, making things harder for the teacher of their next lesson.

For an orderly ending, leave more time than you think you’ll need for those concluding routines – issuing homework, putting away books and materials, tidying work areas. Once they’re done, have the students stand behind their desks in silence. Remind them that you’re expecting them to leave the lesson without any talking.

When you’re happy that they’re ready to leave, let them – but stagger the exit one row or column at a time. Either take a central position or stand at the door and sprinkle some positivity as they go, be it a comment, a smile or a cheery goodbye.

If you end the lesson too early, have an educational game up your sleeve – or maybe end with such a game regularly, thus making it part of your closing routine. Games that incorporate retrieval practice – about that lesson, or one previously – are educationally very helpful.

Stick to your word

The old adage is true – actions really do speak louder than words.

But it’s also true that if you actually do what you say you’re going to do, then those words will be as convincing as your actions.

If you tell the class you’re going to return their homework on Tuesday, then return it on Tuesday. If you tell a student you’re going to phone his mum to let her know how hard he’s working, then phone her.

The same applies to sanctions. If a sanction is stipulated in your school behaviour policy or classroom contract, or you’ve said it’s going to happen, then make it happen.

When what you do is what you say, then what you say will carry the weight of what you do. So stick to your word.

Thank in advance

To bypass the kind of defiance that can arise when an instruction is given, make a point of thanking the student for following your instruction before he or she has actually done so.

Before Jack puts his gum in the bin, for example, say, “Put the gum in the bin, Jack – thanks.” Prior to the point where Jill finally stops chatting to her friend, say, “Thank you, Jill, for being quiet while I read the story.”

Using this technique implies the expectation that the student will follow the instruction – though it’s important to use a friendly tone when doing so, to ensure there’s no suggestion of sarcasm.

On a related note, try to get into the habit of saying ‘thank you,’ rather than ‘please’. ‘Thank you’ is just as respectful as ‘please’, but the latter has something of a begging quality. ‘Thank you’, as explained above, is stronger, since it assumes compliance.

Robin Launder is a behaviour management strategies consultant and speaker. Find more tips in his weekly Better Behaviour online course. For more details, visit behaviourbuddy.co.uk

Negotiating the balance between compassion and discipline

Ed Carlin shares his thoughts on the perpetual struggle to balance effective behaviour management strategies with dignity and grace…

There’s a peculiar dance that teachers can often find themselves performing in the classroom – one requiring a delicate balance between authority and empathy, discipline and understanding.

It’s a dance fraught with challenges, where missteps any can lead to chaos, frustration, and sometimes even a loss of faith in the very system meant to nurture young minds.

Understanding versus challenging

One of the most contentious points in this dance is the question of how to deal with other people’s children. Should you raise your voice? Should you get ‘cross,’ as the British say?

It’s a dilemma teachers face daily, which cuts to the very heart of classroom management and the dynamics of authority. Here’s the thing, though – you shouldn’t have to shout or get ‘cross’ with other people’s children.

In an ideal world, respect and cooperation will flow naturally, but as we know, reality often proves otherwise.

Resorting to anger or aggression is seldom the answer when it comes to behaviour management strategies. It only breeds resentment, creates distance and rarely solves the underlying issues at hand.

Our unsung teacher heroes of the education system thus find themselves too often torn between understanding behaviours and effectively challenging them.

It’s a tightrope walk between compassion and discipline, where each step must be carefully calculated so that you can maintain order, without sacrificing empathy.

Choppy waters

Imagine working in a school where you lack the authority to remove a disruptive student from your classroom. The burden of maintaining order is squarely on your shoulders, yet your hands are tied.

Should you still be held responsible for classroom management under such circumstances? It’s a question that remains hotly debated among teachers and school leaders.

If teachers ultimately don’t have the option to remove someone from their classroom, why should the classroom management buck stop with them?

It seems unjust to expect teaching staff to navigate choppy behavioural waters without access to the full complement of necessary behaviour management strategies or the authority required to use them. How can one be held accountable for a ship they have little control over?

Even in less pressing situations, teachers can experience moments when they’re limited in the sanctions they can impose. Is it ever acceptable to simply ignore certain kinds of behaviours when recourse to certain sanctions isn’t available? Or does doing that simply paint a target on your back?

It’s a Catch-22. Intervening as you feel necessary may invite backlash, while simply turning a blind eye feels like a betrayal of duty.

The power of presence

Worryingly, there are some schools in which teachers are now advised to only intervene with respect to high-level disruption or urgent safety issues.

There will arguably be more options available to you in such instances, but what about the grey areas? All those low-level disruptions that steadily chip away at the fabric of learning, slowly eroding morale and focus over time?

Then there’s challenge of managing behaviour outside of class. Here too, debate rages over whether ‘over-supervision’ is counterproductive, and that behavioural monitoring should be of a ‘light touch’ variety where possible.

However, we shouldn’t underestimate the power of presence as a behaviour management strategy. The subtle influence of a watchful eye can work wonders in steering a wayward ship back on course. Even then, though, the easy option can be to keep quiet, appear agreeable and simply go about your own business.

What about the power of voice? The importance of setting expectations and holding firm to standards, even in the face of adversity? And what, indeed, of swearing and shouting in and out of classrooms?

All too often, there’s an absence of any wider behaviour management strategy that grants teachers the freedom and flexibility to issue appropriate sanctions in response.

The middle ground

We should strive wherever possible for learning environments that are free from hostility and disrespect. So, where do we draw the line between tolerance and tacit approval?

In the end, the answer perhaps lies in finding a middle ground – an equilibrium where authority, empathy, discipline and understanding can coexist harmoniously. It’s a journey fraught with challenges, to be sure, but one that holds the promise of growth, improved resilience and ultimately, transformation.

Example 1 – The power of presence as a behaviour management strategy

In the busy corridors of St. Francis High School, veteran English teacher Mrs. Garcia held sway with a quiet authority that commanded respect.

One day, as she supervised the crowded lunch period, she noticed a group of students growing increasingly rowdy near the canteen entrance. Instead of raising her voice or rushing to intervene, however, Mrs. Garcia maintained a calm demeanour and simply positioned herself within earshot of the unruly group.

Within moments, the students, sensing her watchful gaze, gradually quieted down, their boisterous laughter tapering off into hushed conversations.

Without a word spoken, Mrs. Garcia had effectively diffused a potentially volatile situation, demonstrating the power of presence as a behaviour management strategy and the importance of quiet, steady leadership in managing the dynamics of a school’s shared spaces.

Example 2 – Setting expectations

At the same school, Mr. Johnson found himself facing a daily battle against the pervasive influence of a local gang culture. Despite encountering numerous challenges in his classroom, he remained steadfast in his commitment to creating a safe and nurturing environment for his students.

One afternoon, during a heated discussion relating to Romeo and Juliet, tempers started to flare between two students, each from rival neighbourhood factions. Sensing the imminent danger, Mr. Johnson calmly intervened, his voice firm but measured as he reminded both students of the classroom rules and expectations.

Rather than escalating the confrontation or resorting to punitive measures, Mr. Johnson chose to address the underlying issues with empathy and understanding – using the incident as a teachable moment to foster better dialogue and promote conflict resolution skills among his students.

The takeaway

In both instances, these teachers exemplified the principles of effective classroom management, the power of presence, the importance of setting expectations and the need for empathy and understanding in navigating the complex dynamics of student behaviour.

As we reflect on their stories, let’s remember that the silent struggle of classroom management isn’t just about maintaining order, but also about fostering growth, resilience and ultimately transformation in the hearts and minds of our students.

So when you next find yourself in the classroom, remember this – you are responsible for clarifying and repeating expectations when they’re not met.

And yes, you will indeed be expected to navigate the stormy seas of classroom management with both grace and dignity. Above all, you’ll be expected to lead by example – inspiring those in your care to rise above the tumult, and embrace the endless possibilities that lie ahead.

Ed Carlin is a deputy headteacher at a Scottish secondary school, having worked in education for 15 years and held teaching roles at schools in Northern Ireland and England.

Why students do better when we empower them

Graham Chatterley explains how you can break self-perpetuating behaviour cycles that do little to help children or staff…

If, as parents, we go to our own child’s parents’ evening and get the feeling that the teacher doesn’t really know or doesn’t like our child, how does that make us feel?

We may have spent five minutes with someone and our feelings towards them are negative; we don’t want to listen to what they have to say, and we are probably quite defensive (or aggressive, depending on how we choose to defend our child). If pupils have the same perception, and as a result feel disliked or unwanted, this is not a good foundation for learning. Children who feel this way will be less likely to reach their potential because they will always hold back.

Trending

If we want our children to invest in us and in the lessons we teach, then we must invest in them first. Many children behave in ways that make it very difficult to feel anything positive towards them – they know exactly what buttons to push. But if we can find a way to convince the child that we are still going to like them, no matter what they do, then amazing things can happen.

Feelings stick

If you think back to your own time at school, you probably won’t remember subjects or lessons, but you will remember individuals. You won’t remember the content of classes, but you will remember how you felt in them.

My outstanding memory of high school was the headteacher who came and sat next to me after I was given out in the school cricket final.

I was desperately disappointed, and giving myself a really hard time, so I went to sit on my own. I have no memory of what the conversation was about, and he didn’t attempt to make me feel better or fix what had happened. He just sat with me and talked.

Nothing spectacular. No grand gesture or lesson that had taken three weeks to plan. It was a simple connection that helped at the time, and 20 years later I still remember vividly how it made me feel. It was Y10, and this was the only one-to one interaction I ever had with Mr Wright, who sadly died the following year – but it makes me wonder how many others he impacted on in the same modest way.

We get so caught up in systems and policies that we forget the most important tool we have. Human connection – how we make the children feel – is what ultimately makes the difference in a school, not what we do.

There are no magic strategies to manage behaviour. I was a well-behaved child, but I wasn’t a spectacular learner generally. However, I tried harder for some teachers than others, and if Mr Wright had taught me, I would have gone through a wall for him after that day.

Validate, don’t fix

If we expect behavioural mistakes to happen, but teach children how and why to respond to these occurrences, then we empower them.

Nobody wants children to become distressed. Nobody wants children to react with fear, or to be fuelled by chemicals like adrenaline or cortisol (stress hormones that prepare the body for fight or flight). But they are part of life, not just school. These hormones regulate a wide range of processes throughout the body, but too much of them over time can cause significant harm.

Teaching children how to deal with fear and stress should be part of what we do in the classroom. If we can use our relationships to support, and our connections to replace that cortisol with oxytocin (a bonding hormone that plays a huge role in connection and trust) and increase levels of dopamine (the pleasure hormone), then we reduce fear, drive connections and make young people feel loved.

If we have pupils who feel good, and know the power of making others feel good, then behavioural mistakes will decrease naturally without the need for a specific behaviour focus. They will also be in a state that is more conducive to engagement and more effective learning.

Perfection and punishments

Currently, many behaviour systems run the risk of creating an environment where behavioural mistakes are unacceptable and only perfect will do; anything less results in punishment, often in a way that has no link to the original behaviour.

If we don’t know why they are getting it wrong, how can we teach them to get it right? For example, a child who perceives a psychological or mental threat (and whose body floods with stress hormones) is likely to get into trouble because this type of active survival response isn’t appropriate.

Don’t ignore the mistake. Instead, see it as a chance to learn, connect, raise self-esteem and teach better responses. If someone has been wronged, a consequence will be necessary. But we must link it to the behaviour and give the child an opportunity to repair and redeem themselves.

Without this, we feed into the child’s narrative that they are bad and need punishment. This is a narrative that will become harder and harder to change if we don’t challenge it.

Shame loops

In my school, there were many children who were impulsive, who would perceive a threat, storm out of the classroom and rip down the first display they encountered.

They were dysregulated and had no interest in the display because they weren’t thinking rationally. The priority was to get them calm. Then we could discuss the behaviour.

When the initial response is punishment, the result is a child who believes that they behaved in the way they did because they are bad, and therefore they deserve punishment. They will take the punishment. And then they will make a similar behavioural mistake the next day because they are bad, and that’s all we can be expect of them. This is a shame loop.

Shame vs guilt

Instead, we need to look at the impact of the action, rather than the action itself. If the child understands that their favourite staff member spent hours putting up that display and will be upset about the damage, then the behaviour means something. The child feels guilty.

An expectation that they repair the action becomes not only a logical consequence, but of importance to the child. Often, I couldn’t give that child a staple gun fast enough to fix the damage.

When guilt is used to drive repair, not to feed shame, the child’s narrative changes: ‘I’ve done a bad thing, but I’m not a bad child’ is a driving force for accountability, and making amends brings with it change. If bad things can be fixed, then so can faulty beliefs.

Giving the gift

If the child has experienced how satisfying it feels to do good things, then we can keep reminding them of this feeling. Over time, the positive things win out because the child believes they can do them.

Starting with adrenaline and cortisol, and finishing with oxytocin and dopamine is a powerful process and journey. Take that path enough times, with enough connection and safety, and the adrenaline and cortisol aren’t required and negative behaviour will reduce.

For many of us, there comes a point in our lives when giving the gift becomes more satisfying than receiving it. Getting something nice is great – we get a short-term buzz – but the feeling we get from creating and seeing that in others lasts longer and gives us more. This is what we must teach our children.

Graham Chatterley is a former school leader who has since led training for thousands of educators across the North of England; follow him at @grahamchatterl2. This article is based on an extract from his book, Changing Perceptions: Deciphering the Language of Behaviour (Crown House Publishing, £17.99).

Post-Covid behaviour management strategies for teenagers

Post-Covid, teachers are contending with teenage behaviours they’ve never encountered before. Teacher Katie Hill examines what the best response might be…

It’s with an air of caution that we have to talk about the mental health impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. Don’t get me wrong, I certainly don’t believe that every child was permanently scarred by the experiences they had, but there are some huge issues to be understood and worked on to ensure that our young people can thrive in the coming years.

The main issue presently is the lack of teacher training around teenagers’ emotional needs.

We have metacognition in the bag. Work in this area has been incredible over recent years, producing much in the way of theory and practical application, but we now need to look underneath – at the foundations of our students’ attitudes, behaviours and characteristics.

Fear response

We need to understand what our basic needs are as humans, and how we can support our students in ensuring these are met. We also need to understand what is happening to teenagers’ brains when they encounter perceived threats.

Covid caused the vast majority of us to become caught in a fear response. When we’re in this response, the most primal part of our brain (the amygdala) acts as a burglar alarm, shutting down much of our ability to think logically and rationally.

It’s a natural, human reaction, and therefore doesn’t mean we are failing in any way, shape or form. For teenagers, that logical, rational part of the brain is still a work in progress.

It won’t be fully developed until they reach their mid-20s, so their ability to think ahead is limited even further. Instead, their brains are busy deciding whether to leg it as far away as possible, freeze like Anna in Frozen, or fight as though their life depends on it.

Pupil behaviour – flight, freeze or fight

You’ll probably be able to categorise your students quite quickly into one of those three categories – flight, freeze or fight. Why is this useful?

Because when those moments occur, we know it often isn’t because students are ‘playing up’, but because they perceive threat, whether it be their best friend kissing their girlfriend or an assignment they can’t begin to comprehend.

So how should we tackle these flight, freeze and fear moments? The key is in soothing the amygdala and meeting emotional needs. If we’re able to calm that primal part of the brain, we leave space for the strategic part of the brain (the pre-frontal cortex) to develop more effectively.

If we look at the five emotional needs developed by Dr Gerald Newmark (founder of The Children’s Project), the two that stand out as most lacking during Covid were ‘control’ and ‘belonging’.

As a society, we lost huge swathes of control and became disconnected from our tribes, the latter of which is acutely apparent among teenagers.

Teenage brain development depends on them being able to develop independence and break away from parental bonds to build their own social networks and attachments.

We know this if we look back at the powerful, intense bonds that many of us developed at a similar age (however fleeting they may have been!).

Disruptive behaviour

This lack of control to make decisions, and the restrictions placed on being able to join a tribe, will have left a potential gap in our students’ essential development.

We might see this expressed in:

- ‘low-level disruption’ (or a need to connect and socialise)

- loud voices in the classroom (or the need to express a desire to belong to the pack)

- ‘inappropriate behaviour’ (or the need to relearn the structures and guidelines involved in being part of that tribe)

Alongside these issues, we can’t forget the overload that many of us experience when our ‘brain bandwidth’ is at its full capacity.

Brain bandwidth

If we consider, as Nicola Morgan (AKA The Teenage Brain Woman) does, that every mental and physical action takes up some bandwidth, and that this bandwidth is finite, we can acknowledge the sensations we feel of being overwhelmed when we’re approaching capacity.

Tasks we’re very familiar with, such as walking, take up very little bandwidth. New challenges, such as adjusting to extended hours of screen time and conducting online conversations, can take up a lot.

If we apply this understanding to the transition our students have made over the past few years, it’s hardly surprising that the ‘brain bandwidth burnout’ is very real.

We also know that if emotional needs aren’t met, the likely consequence will be a long term impact on mental health that could manifest as anger, anxiety or depression. There’s no clear, linear explanation for how or when these issues arise.

There’s still much to be done in the world of neuroscience. But what we can do in the meantime is spread awareness among ourselves and our students – by which I mean more than just one additional form time session dedicated to teenage brain development.

Behaviour management strategies to help school staff nurture wellbeing

What we’re suggesting is to include a whole school focus on emotional wellbeing in school development plans, assemblies and PSHE lessons. Engage students in the physiological and psychological impact of stress, and pledge to prioritise wellbeing for your whole school community.

At a cultural level, this might mean normalising the struggles we all encounter as humans, acknowledging that resilience isn’t something you’re good or bad at, and defining what exactly we mean by ‘nurturing wellbeing’.

In more practical terms, it might also mean providing more opportunities for whole school mindfulness, creativity, sport, fun and community cohesion.

It may involve devising ways of engaging parents as vital players in the school ‘tribe’, providing more opportunities for students to connect with each other and socialise and spotlighting the power of gratitude – because ‘thank yous’ go a long, long way.

As teachers, we’re tasked with filling in gaps, providing safe spaces, inspiring life-long learning and being a constant source of support for our students. We are held more accountable than ever for students’ grades, and the burden of unknowns weighs heavy.

And yet we also have more power than we realise to embed new cultures in education – because learning is nothing without the substructure of fulfilled emotional needs.

5 steps to post-Covid wellbeing and positive behaviour

- Organise discussion and training around the ‘fear response’, brain development and how we respond mentally and physically to stress

- Integrate the inherent need for ‘control’ and ‘belonging’ into everyday school life

- Give students and staff the space and time to switch off from activities that lead to ‘brain bandwidth burnout’

- Prioritise ‘wellbeing’ as more than a tick box exercise; ask staff and students what they really need and listen

- Acknowledge the power we have as a collective to make wellbeing an educational priority

Katie Hill is a teacher in Cornwall. She provides training for teachers and students on emotional wellbeing.

What research says about rewards systems as a behaviour management strategy

Our reward systems may be doing the exact opposite of what we want them to do, but research does offer us guidance we can use to steer our efforts more effectively, explains Alex Quigley…

Reward systems are seemingly obligatory for schools. Every educational institution has its own, unique concoction of treats lined up to be doled out for achievements, like a display of goodies in a sweet shop.

You can take your pick from Harry Potter-like house points, alongside an array of vouchers, prizes, apps, and more. But can we be sure that this is the right approach?

In fact, we know a great deal about human motivation, regardless of our apparent relish for rewards. There are actually two common types of behaviour drivers that prove useful for teachers.

First, there is ‘extrinsic motivation’, where our actions are prompted by an external reward, such as points, money, vouchers and so on.

And then we have ‘intrinsic motivation’, which is when we are moved to behave in a certain way by some kind of internal reward, like the natural satisfaction of completing a great essay or piece of artwork.

As every teacher knows, it is this latter attitude that we really look to cultivate in our students.

We want even our most reluctant of teens to see the value in learning for its own sake. We strive for them to find their passion for history, art, literature, and more, without needing the promise of a carrot to nibble on at every stage.

From the inside

A commonly held notion is that dangling the carrot of rewards helps increase our students’ motivation, at least in the short-term, and consequently drives them on to better achievement. And yet psychologists have long criticised this simplistic notion of human behaviour.

Indeed, in a large research review of motivation, Deci et al (1999) revealed that: “Even when tangible rewards are offered as indicators of good performance, they typically decrease intrinsic motivation for interesting activities.”

Potentially then, our reward systems may be doing the exact opposite of what we want them to do! However, the research does go on to give us guidance we can use to steer our efforts more effectively.

It may well be that extrinsic rewards do help to spike motivation with simple tasks, but the evidence would suggest that with complex learning tasks they make little or no positive difference.

If students associate producing great homework with scoring a couple of house points, then what happens when they need to complete a particularly difficult task, or revise for their exams, without the fuel of point-scoring highs?

If we are to have reward systems at all, we need to tread a fine line, judiciously making use of appropriate prizes whilst still convincing our students that making progress and learning is a reward in itself.

Evaluate the impact

It’s possible to devise a workable system for contacting parents about sustained exceptional effort, for example, without resorting to dishing out points for completing required work or simply exhibiting good behaviours that we would expect of every child as standard.

Being aware of the pitfalls of extrinsic rewards goes a long way to mitigating their potential negative impact – so, you may choose to reward a student for an exceptional piece of homework, but not for simply finishing an assigned task.

Of course, when we are dealing with the psychological uncertainties of human behaviour – never mind the unpredictable brain of a truculent teenager – we can never be certain of the response to any intervention we might try.

That’s why we really should make a concerted effort to evaluate the impact of any rewards we use. First, we can question teachers about their attitudes and monitor their actions (perhaps they are not issuing the rewards we think they are, or they could be doing something even more successful than the ‘official’ points system).

Then survey students. Are our rewards outdated – such as meaningless vouchers, or tokens that go unused? Are they influencing attitudes or behaviour changes at all?

After evaluation, we may well decide that the carrots of extrinsic reward still have a place in our school; but ultimately, thinking harder about exactly how we can best motivate our students to succeed must always be a valuable exercise.

Alex Quigley taught for more than 15 years and now works for an educational charity and offers consultancy.

Take control of behaviour in just 15 seconds

According to behaviour management strategies trainer Rob Plevin, this simple routine can take your students from rowdy to rapt in a quarter of a minute – what have you got to lose?

If you’re not already using routines (or ‘procedures’ to some) in your classroom, then you should be. They can literally transform your teaching overnight, putting your basic instructions on autopilot and making your job much easier.

The first big benefit is saving time – and lots of it. We lose countless minutes (each of them precious, of course) by having to repeat instructions again and again to students who aren’t listening.

However, once you’ve invested what it takes to establish routines, the job of getting everyone to follow your instructions is largely done for you. The routine reminds them exactly what to do, and how to do it.

Routines give your students a map to follow, and 100% consistency, which is crucial. They also offer young people a greater chance of experiencing success in your lesson – and for our tough, most challenging learners this can be something they rarely get to enjoy.

By giving them very clear steps to follow in order to complete a given task, you dramatically increase the likelihood of them doing the right thing. And the more opportunities you have to praise students and thank them for behaving appropriately, the more quickly their attitudes and behaviour will change for the better.

Two principles for success

Not only can the technique I’m about to explain get a group of learners quiet in as little as a few seconds once the routine has become established, it also strengthens teacher–student relationships, injects some humour into the session and gives challenging youngsters the attention they crave.

Moreover, it works equally well with 8-year-olds, 18-year-olds, 18-year-olds and even 63-year-olds. Indeed, when I tried it at a teacher training seminar in Dubai I overheard one of the participants remarking, “He just got a room of 150 rowdy people quiet in 15 seconds!”

It relies on two key principles: responsibilities and routines. Some of your students will respond very well when you give them a responsibility. In fact, it’s probably your most challenging young people – the ringleaders – who will respond best to responsibility, because they crave attention.

Nominated shushers

A great way to give them this attention (in a very positive way) is to give them a job, and for this classroom strategy we are going to award three or four of your liveliest learners the job of getting the rest of the class quiet. These students are going to be our ‘shushers’ and it is their responsibility to ‘shush’ the rest of the class members (in a special way) when asked to do so.

To give our selected few every chance of success we are going to train them. Each nominated shusher is asked to give their best and loudest shush – complete with angry scowl and finger-on-lip gesture. After a few practices, the shushers are then told that whenever the teacher shouts out ‘Shushers!’ they are to give their best and loudest shush in unison. The rest of the class are told that when they hear the shushers shush, they must stop talking and sit in silence.

After two or three practices they all get the idea and we now have the makings of a very effective routine in place.

Three added ingredients

To give the shushing routine the best chance of success there are three additions which I have found to be useful.

First, your shushers need regular feedback. They should be told when they are doing a good job and given hints and pointers when they are slacking or messing around. Remember that the students you use as shushers are likely to be natural livewires so they will need careful management to make sure they continue to perform well.

Ideally, any constructive feedback or corrective instructions should be given quietly, and out of earshot of other learners.

Second, I like to give each of my shushers a uniform to wear so they can be easily identified. The ‘uniform’ is actually just a silly hat or joke shop cap, but they love wearing it, although I’m not entirely sure why. Maybe it helps them feel special, perhaps it just makes the whole affair less serious, but whatever the reason, it seems to work.

The countdown

Finally, I have found that shushers sometimes need a little extra help to get a particularly rowdy class to settle. I give them this by using another routine prior to calling on them – the countdown. This is simply the process of counting down from ten to one out loud, while giving encouragement along the way/

Example

| 10… | Okay everyone, by the time I get down to one you should all be sitting on your own seats with your bags away and your hands on the table… Excellent, Carly and Sophie, you got it straight away. |

| 9… | Brilliant over here on this table – let’s have the rest of you doing the same. |

| 8… | You need to finish chatting, get that mess away and be sitting facing me. |

| 7… | All done over there at the back, well done. Just waiting for a few others. |

| 6… | Come on, still some bags out at the back and people talking. |

| 5… | Good. |

| 4… | |

| 3… | We’re just waiting for one group now. Ah, you’ve got it now and you’re sitting perfectly, thank you. |

| 2… | Well done everyone, nearly there… |

| 1… | Brilliant. |

| [Pause] | |

| Shushers! |

By the time you reach one, most of your students will be settled and responsive, leaving the shushers to deal with the small minority who are still talking. Obviously, you can shorten the countdown or even disregard it completely, if a group is relatively settled to start with. At these times, the shushers alone can bring silence to your room.

So there you have it. A great way to get rowdy groups of students settled in record time. Now, let the lesson begin…

Rob Plevin is a behaviour management strategies trainer who has successfully taught in some of the most challenging settings. He is the author of Take Control of the Noisy Class (Crown House, £18.99), from which this idea has been adapted.

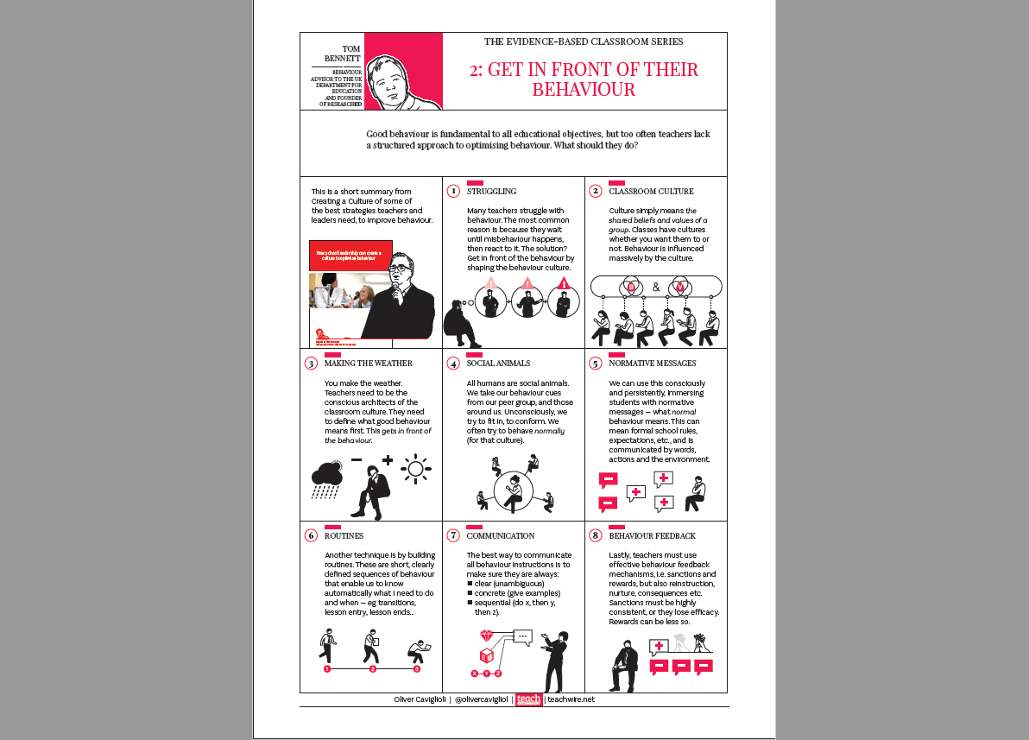

How to use group psychology to influence behaviour

Peer pressure influences behaviour like nothing else – here’s how group psychology will help you control it, according to trainer and author David Didau…

Humans are social animals. Cooperation with others is one of the keys to our survival and dominance as a species. It makes sense that in order to get on with others we’ve evolved a complex range of strategies for maintaining our membership and status within social groups.

Different groups behave differently, but all groups conform to some fairly predictable rules about how to behave. These ‘social norms’ can be explicit rules or unspoken arrangements, but everyone within the group understands the consequences of not conforming to the norm.

Unspoken expectations

Schools, like any other cultural institution, have social norms. There will be formal rules about how students should behave, but students will also be aware of the unspoken rules, many are based on the unspoken expectations of the teachers and students who make up the school. Powerful as the culture of a school can be, it pales into insignificance next to the influence of peer groups.

Children are primarily socialised through their peer groups. Group socialisation theory predicts that the most important variable for determining children’s educational success is the peer culture at their school. Parents’ values are handed down to children whilst they’re at home and continue to hold sway as long as these are values shared by a critical mass of the child’s peer group. But, if a student with a different background attends the school, they will take on the values shared by their peers and abandon those of their parents. They’ll start to speak differently – at least whilst at school – and they’re likely to take on the group’s beliefs about how to behave at school.

Values and stereotypes

We all want at least three things: to fit in, not to make a fool of ourselves, and to improve our standing amongst our peers. The trouble is, fitting in with our peers and gaining the approval of our group can often be at odds with the norms of a school.

We all know that students can ‘get in with the wrong crowd’. Values and stereotypes can have a lasting influence on group members. If the group values hard work then it becomes important to identify as a hard worker. If our group values mucking about and being defiant, then that’s how we’re likely to identify.

When we find ourselves in situations where we’re torn between two sets of values, we experience ‘stereotype threat‘. All researchers had to do to make female, or African-American students perform worse on a test was to give them a pre-test questionnaire, which included a question about race or gender. Simply being reminded of our group affiliations is enough to trigger the associated stereotypes about who we’re supposed to be.

Shape the ingroup

If you want classes to be successful you need to address the peer culture. Here are three ways you can shape it:

- By defining group norms. You don’t have to influence every member of a group, you just need to nudge enough of the most influential members. This then generates a kind of ‘herd immunity’ against poor choices and bad behaviour.

- By defining the boundaries of the group. We can, to a greater or lesser extent, control who is in and who is out, who is us and who is them. Of course it’s possible for subcultures to form within classes and schools but by engendering strong social norms we can make belonging to the in-group both inclusive and desirable.

- By defining the image or the stereotype students have of themselves. If we encourage students to value hard work and disciplined behaviour in each other, then we will have done our job; they will police the social norms themselves.

This is how successful schools operate. They create an ingroup where ‘we’ are different to everyone out there. ‘We’ feel privileged to be in the ingroup and appalled at the idea of what it must be like to be a member of the outgroup. ‘We’ notice everything that makes us different from ‘them’ and we revel in the differences.

David Didau blogs at learningspy.co.uk and is the author of several books, including What If Everything you Know About Education Is Wrong?. You can follow him at @LearningSpy.

Behaviour management strategies checklist for the new term

The summer break provides an ideal opportunity for you to reflect on how well you have set up your classes at the start of the academic year – particularly if you’re still at an early stage of your teaching career. In what ways have you sought to ensure that your pupils will be successful? How have you looked to maximise their learning time?

Those are both broad questions, so it can be helpful to break them down by devising a checklist. Below is an example that you can use when looking to improve the foundations for learning in your classroom:

1. Entry routines

Do you have a welcoming and effective entry routine for your classroom? Many teachers chose to meet their students at the door, welcome them personally to the classroom and direct them to the first task.

2. Engaging starts

Do your students know how the lesson will start? You could use a retrieval quiz linked to previous work to begin the lesson. This could be either handed out or displayed on the board.

3. Distribution of materials

Have you taught the students a simple routine for ensuring all books and other lesson materials are handed out effectively? Students should be taught to ensure that such items are distributed to everyone in the class as smoothly and as unobtrusively as possible.

4. Student register

What is your own routine for taking the class register, and is it as effective as it could be? It’s important for every teacher to ensure that they complete the register accurately, consistently and on time.

5. Seating plans

Do you use seating plans for your classes? Have you learned your students’ names? If your answer to the latter is ‘no’, seating plans can be a useful aid to memory. They can also help you check instantly whether every student is seated where they ought to be.

6. Awareness of need

To what extent do the aforementioned seating plans contain essential information that will improve your standard of teaching? Examples of this might include details of which students are in receipt of Pupil Premium or have SEND, as well as reminders of previously agreed personalised strategies or prior attainment information.

7. Check your position

When teaching, do you take up a good position in the classroom where you’re able to see if all students are paying attention to you and are engaged? Scanning the class constantly, while simultaneously teaching or speaking, is a crucial skill for ensuring that every student remains focused.

8. Clarity regarding participation

When teaching, do you make the means of participation clear to all students, so that they can meet your expectations? Always clearly explain to students if and when they should put up their hands, or when you’re intending to use a ‘no-hands technique’ such as cold calling.

9. Class circulation

When the students are working, do you move around the classroom to see what work they’re completing? This is a hugely important thing for teachers to do, and means that when you check students’ work later, you are less likely to encounter any surprises.

10. Recognition and rewards

Take time to recognise those students who meet or exceed your expectations, and be sure to make regular use of your school’s reward or recognition system. That way, you can start building lasting and positive relationships with students as early on as possible.

Daniel Harvey is a GCSE and A Level science teacher and lead on behaviour, pastoral and school culture for an inner city academy.