Banned Books Week – Best UK teaching resources

Want teens to read? Letting them know which books certain authorities don’t want them to see might be a good place to start…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Banned Books Week is a brilliant way to spark discussions with your students about censorship, freedom of expression, and why some stories get silenced…

Table of contents

What is Banned Books Week?

Banned Books Week started in 1982. It’s now an annual event celebrating the freedom to read and the value of free and open access to information.

It’s more important than ever, with a survey by Cilip showing that librarians are increasingly being asked to censor or remove books.

In another survey, 53% of school librarians said they had been asked to remove books, with more than half of the requests coming from parents. Books removed included:

- This Book is Gay by Juno Dawson

- Julian is a Mermaid by Jessica Love

- ABC Pride by Louie Stowell, Elly Barnes and Amy Phelps

As recently as August 2024, major book publishers have sued the US state of Florida over a law that allows schools to ban certain books.

When is Banned Books Week?

Banned Books Week takes place between 5th-11th October 2025.

Banned Books UK list

According to a list compiled by Index on Censorship and Islington Council’s Library and Heritage Services, these are just some of the young adult books that have been banned or challenged since 2000:

- Gossip Girl by Cecily von Ziegesar

- Twilight by Stephenie Meyer

- The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

- The Miseducation of Cameron Post by Emily Danforth

- The Fault in our Stars by John Green

- The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas

Banned Books Week resources

Judy Blume on banned books

Over on the Banned Books Week YouTube channel you’ll find some great videos on titles that have caused a stir, as well as many famous authors talking about their works being banned.

In this video, frequently-censored author, Judy Blume, discusses the effect that book censorship has on children.

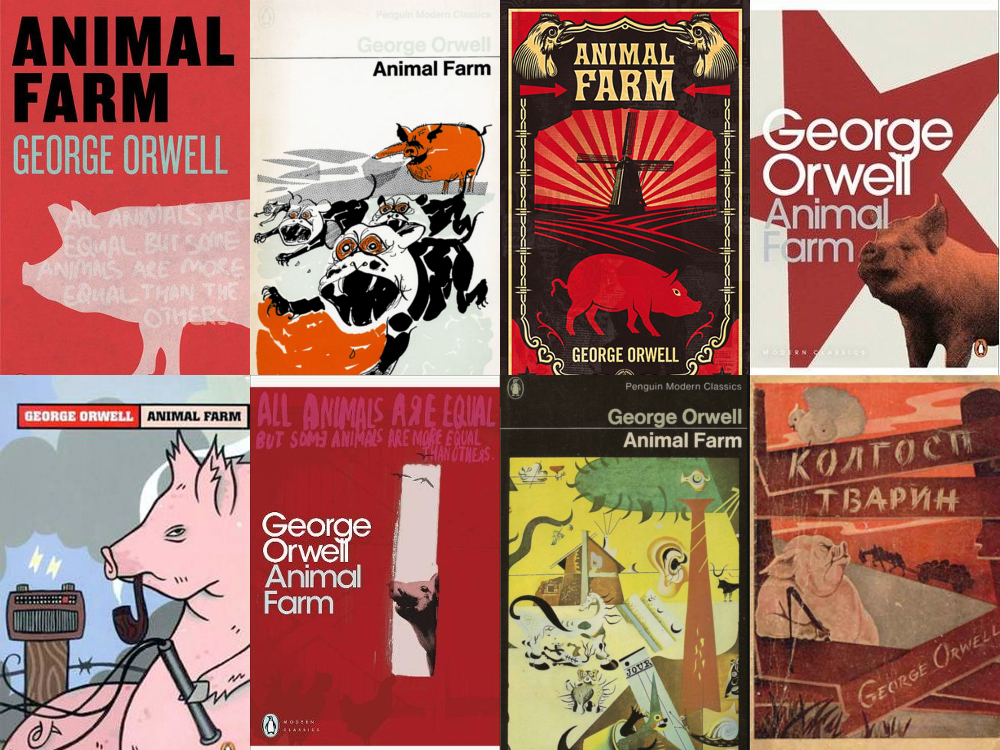

Animal Farm resources

Animal Farm‘s critique of totalitarian regimes, particularly Soviet-style communism, made it controversial in countries with communist or authoritarian governments.

For many young readers, Orwell is a first dalliance into politics. The classroom is the perfect setting for studying this masterpiece and we’ve put together a list of great resources for studying Animal Farm.

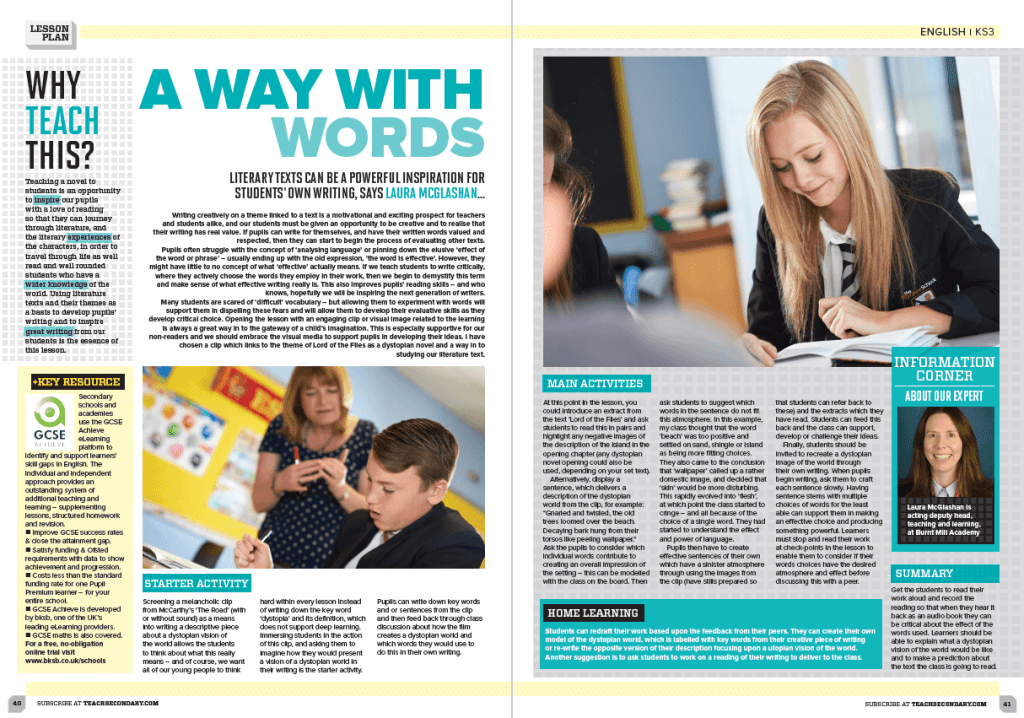

Lord of the Flies resources

Lord of the Flies has been banned from libraries and schools over the years due to its graphic depiction of violence and its dark portrayal of human nature.

This free lesson plan uses a clip linked to the theme of Lord of the Flies as a dystopian novel. Pupils often struggle with the concept of ‘analysing language’ or pinning down the elusive ‘effect of the word or phrase’.

By teaching students to write critically, actively choosing the words they employ, we can begin to demystify this term.

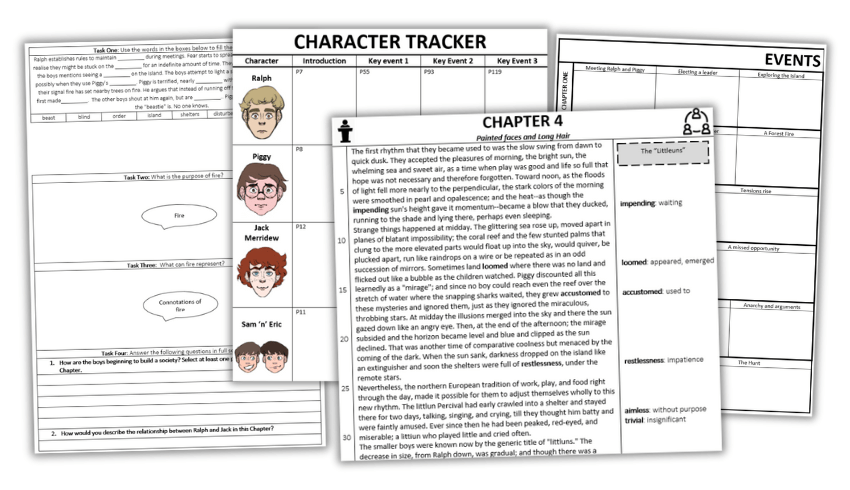

This free Lord of the Flies chapter summaries course reader provides comprehensive support for teaching William Golding’s classic novel to younger secondary students.

Use The Great Gatsby to get students talking about literature

F Scott Fitzgerald’s exceptional The Great Gatsby is one of the most challenged books in American schools due to its depictions of sex, alcohol and moral decay. However, it’s a masterpiece of literature and an exceptional allegory of America itself.

In this lesson you’ll find fun and engaging activities to inspire a love of critical analysis. Students will look at the rivalry between Tom and Gatsby in Chapter 7.

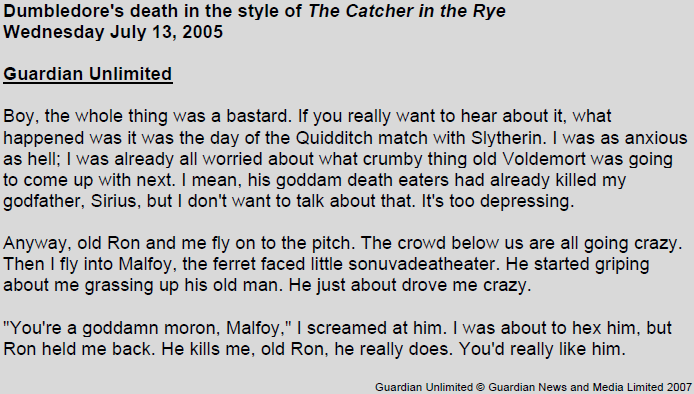

Harry Potter and Holden Caulfield

Both JK Rowling’s Harry Potter series and JD Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye regularly feature in banned books lists, and this resource combines them both to look at the voice used to create Holden Caulfield.

Dystopian novels discussion

This list from Nic Worgan offers discussion points for five famous dystopian novels – The Road, Divergent, Never Let Me Go, 1984 and The Handmaid’s Tale. The last three often appear on banned or challenged book lists.

If you want to delve deeper than these discussion points for Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go and explore themes of human cloning, ethics and mortality – we’ve also rounded up six great teaching resources for that title.

Craziest reasons books were banned

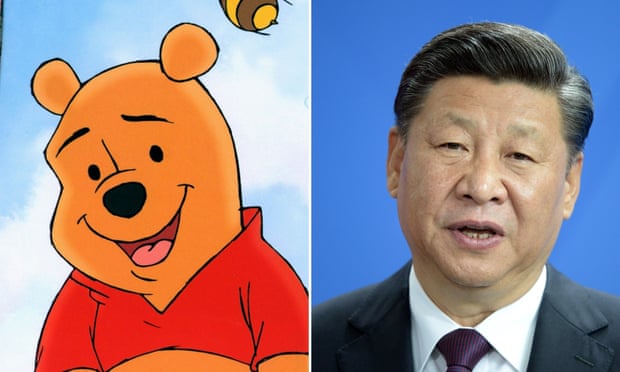

- China banned Winnie the Pooh in 2018 as people were mocking President Xi because of his resemblance to the beloved bear.

- The anti-racist To Kill a Mockingbird was banned in schools in Lindale, Texas for ‘conflicting with the values of the community’. Another Texas board banned Moby Dick for the same reason.

- Dr Seuss books have been banned in American schools for a number of reasons. The Lorax, for example, was banned for its ‘criminalisation of the logging industry’, but other books were banned for supposedly promoting homosexuality and Marxism.

- Charlotte’s Web, Animal Farm and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland are just some of the famous examples of books banned in various parts of the world for featuring talking animals.

- Zen Buddhism: Selected Writings was banned in Michigan for describing the teachings of Buddhism “in such a way that the reader could very likely embrace its teachings and choose this as his religion.”

- The Diary of Anne Frank was banned in certain places in the US, but not just for the sexual passages. Nope. Apparently someone thought it might be “too depressing” to read.

Why we shouldn’t push children to be the readers we want them to be

There’s no such thing as a non-transferable piece of reading, so we need to be very wary about what we ban or sniff at, says author Robin Stevens…

As a children’s author, there are many things that I want my books to give their readers. I’d like them to teach children how to be kind, how to think more deeply about the world and how to be resourceful and brave in the face of the huge odds that life will throw at them.

I’d hope that they will expand children’s vocabularies and broaden their minds. But there’s one basic thing I know: if kids aren’t enjoying reading my books, they will put them down. Then none of those high ideals will be possible.

Clear win

I love reading so much that it’s hard for me to be dispassionate. But I know that plenty of studies have shown that children who read have wider vocabularies, are more confident constructing sentences, do better in lessons, have broader general knowledge and are more empathetic.

Reading is therefore a clear win. And we, as adults involved in children’s education, want desperately to get that win for the children we work with.

We all try to encourage kids to read widely and often. But sometimes I think that we are trying so hard that we forget that basic principle: for a child to read, they must not only enjoy reading in general, but the book they are reading in particular.

Tiny tragedies

A few weeks ago, a 14-year-old fan got in contact with me to tell me that she loves my books, and has read them all. But she reads them at home, because at school her teacher has told her that she is too advanced for them. This isn’t the first time I’ve been confronted with this issue.

At a signing late last year, an 11-year-old leant over and whispered in my ear, ‘I wanted to buy more than one book, but my teacher says that your books aren’t proper ones.’

“My teacher says that your books aren’t proper ones”

And it’s not just my books. I’ve been witness to more tiny bookshop and library tragedies than I can count, where a glowing, excited child points out a book they want to read, only for their adult to turn to them and say, ‘That’s too young for you. Pick something else.’

The idea of being ‘too old’ for a book, or that a book can be ‘too fun’ to be worthwhile, is one that is pervasive – and, I think, damaging. We imagine reading, like the process of growing up itself, as a ladder, one that must be steadily climbed by each child.

If a child can read Dickens, why should they read Blyton? A pupil knows the word ‘circumnavigate’? What are they doing messing about with Beast Quest?

“If a child can read Dickens, why should they read Blyton?”

But I would counter that what they are doing is, in fact, the most important thing of all. They are enjoying reading.

Enjoyment

Reading is not a ladder. It is a universe. Think about the adult reader you are now. Are you someone who only ever reads Proust? I’m certainly not.

I read Booker shortlistees, thrillers, romances, YA, sci fi, comic books, murder mysteries and children’s books – anything, essentially, that I enjoy, and I don’t expect any child to be different.

Then there is the question of rereading. We see a reader cycling through the Wimpy Kid series 12 times (12 times, we fret. When they are all basically the same book!).

What if they never grow out of it? What if they become an adult who has only ever read Wimpy Kid? The panic is so understandable, but I think it’s important to put it into context.

“What if they become an adult who has only ever read Wimpy Kid?”

What we fear is not actually likely – and anyway, rereading should not be thought of as lost time. It is the important process of inhabiting a particular story, of studying its text until you are able to step between the words and truly understand what they mean.

It is, in fact, how you engage with a text at the highest academic level. Why should we be concerned that children are practising this skill?

Too many fun things

And what about the worry that a child is not stretching themselves? Or that they’re reading too many fun things to be good for them? I know, from a lifetime as a wide-ranging bookworm, that all words are words. All knowledge is knowledge. All reading is reading. And all stories have something to say about the world we live in.

“All words are words”

I used to dazzle my classmates with my amazing animal knowledge – which I had because I read every single Animal Ark book ever published. I was a Winter Olympics know-it-all – because I had a picture book about a cat who cross-country-skied. Because I read Matilda I knew how to spell Mississippi. I learnt Latin from Harry Potter. I learnt French from Tintin.

There is no such thing as a non-transferable piece of reading. And so we need to be very wary about what we ban or sniff at.

“We need to be very wary about what we ban or sniff at”

When we call a book valueless, we may just be missing the value that particular story has to that particular child. We simply cannot know how reading that story will affect the adult they go on to become.

Fall into a trap

I spend a lot of time working with and speaking to educators, parents and carers. I know how many of you are working tirelessly to give not just reading but reading enjoyment to the children in your lives.

I’ve been delighted and heartened to hear the responses to my initial tweet about that 14-year-old. So many of you understand not only how powerful reading can be, but how crucial enjoyment is to it.

But I know that the drive for constant improvement (both from the curriculum and elsewhere) can make it terribly easy for even the most well-intentioned adult to fall into the trap of pushing a child to read against their own enjoyment.

And it is our good intentions, our desire for children to be heaped with knowledge, that can sometimes backfire.

You can never be too old for a book, but you can be too young. If we push our children to become readers despite themselves and beyond what they love, we run the distinct danger that they may not become readers at all.

Robin Stevens is the author of the Murder Most Unladylike Series.