Character description – Best resources for KS1/KS2

Create characters with depth, desires and three dimensions with these excellent activities, ideas, lesson plans and more…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

There are many parts of the National Curriculum that might require a quick Google refresher each time it comes to teaching it (which ones are causal conjunctions again?). But thankfully, character description is something that comes to us fairly naturally in childhood.

But, there is of course more to great character descriptions than simply being able to describe what a person looks like. That’s where these resources will come in handy…

Character description resources

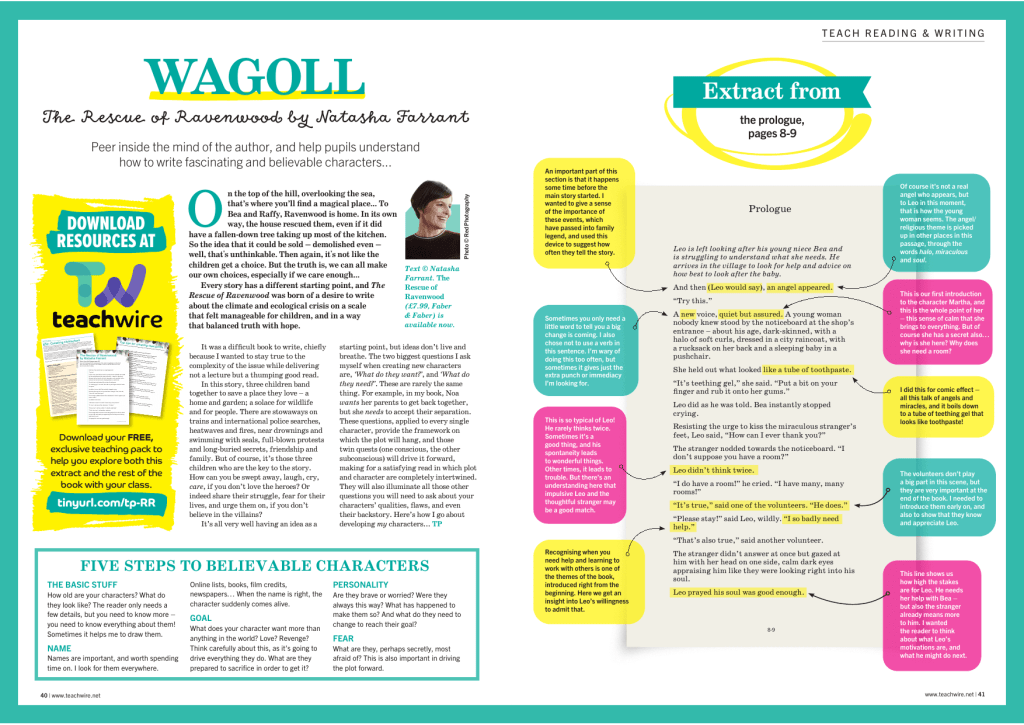

Character description WAGOLL

Use this free character description resource pack to teach your students how to write interesting and realistic characters. The example in the resource comes from the book The Rescue of Ravenwood by Natasha Farrant.

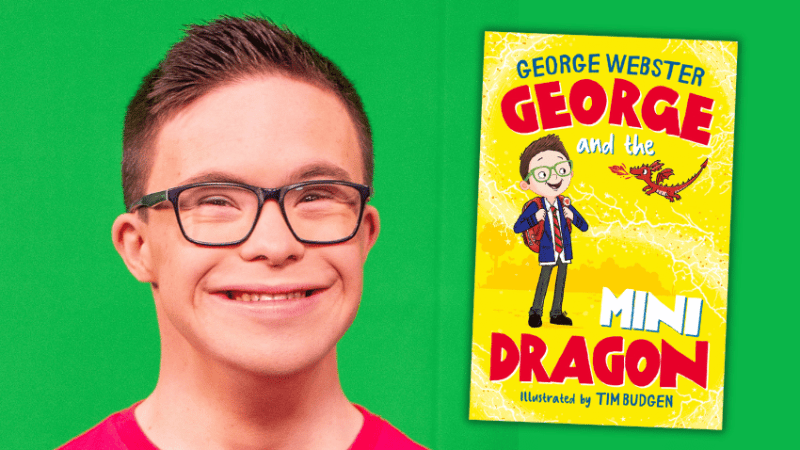

Creating characters with Sam Copeland podcast and resources

Help KS2 children to create vibrant, believable, complex characters with expert advice from Sam Copeland, author of the ‘Charlie McGuffin’ series of books, in which the eponymous hero changes into random animals when he gets stressed.

This free resources pack from Plazoom is designed to be used with episode two of the Author In Your Classroom podcast, a virtual ‘author visit’ you can share with children whenever you like, absolutely free!

The pack includes accompanying resources including a PowerPoint, teacher notes, book extracts in print and as audiobook clips, illustrations and author quotes for a working wall display. There’s also story planning and writing sheets.

Describing Goldilocks KS1 lesson plan

Is the story of Goldilocks as clear cut as you might think? Did she go in, uninvited, to the three bears’ house and cause criminal damage? Or maybe she was lost and needed the shelter or had another pressing reason to go in?

In this lesson, children will explore the character of Goldilocks and come to their own conclusions about what she was really like, using the book Me and You by Anthony Browne, which describes itself as ‘a thought-provoking take on the Goldilocks story.’

They’ll learn how to read between the lines by inference and deduction on words and pictures, and they’ll build a profile of a well-known character through interpreting and discussing evidence.

KS2 character description lesson plan

Have fun discovering new characters and places with drama techniques from the National Theatre’s Let’s Play programme. This free lesson plan uses a fun and creative way to introduce any new story, book or play to your class.

You can do all these activities before reading the text for the first time. They involve considering what characters are thinking and feeling. These tasks let all pupils get into the story you’re studying and help them understand the story better.

Describing spooky characters LKS2 writing resources pack

Inspire pupils in Year 3 and 4 to write engaging character descriptions using this spooky character description resource pack from Plazoom.

Read the model text ‘The Wizard’ and explore how the author has described a character, including information about what they look like, where they live and their character traits.

As well as the text, this resource pack includes a creating characters ideas sheet, vocabulary cards, spooky character cards, object cards, a planning sheet, themed writing paper and teacher’s notes.

Use drama to develop new characters

In this free lesson plan, Sam Marsden shows how you can use a sequence of drama exercises to invigorate pupils’ creative writing.

Using drama exercises can move pupils from staring at a blank page to creating powerful stories with believable characters.

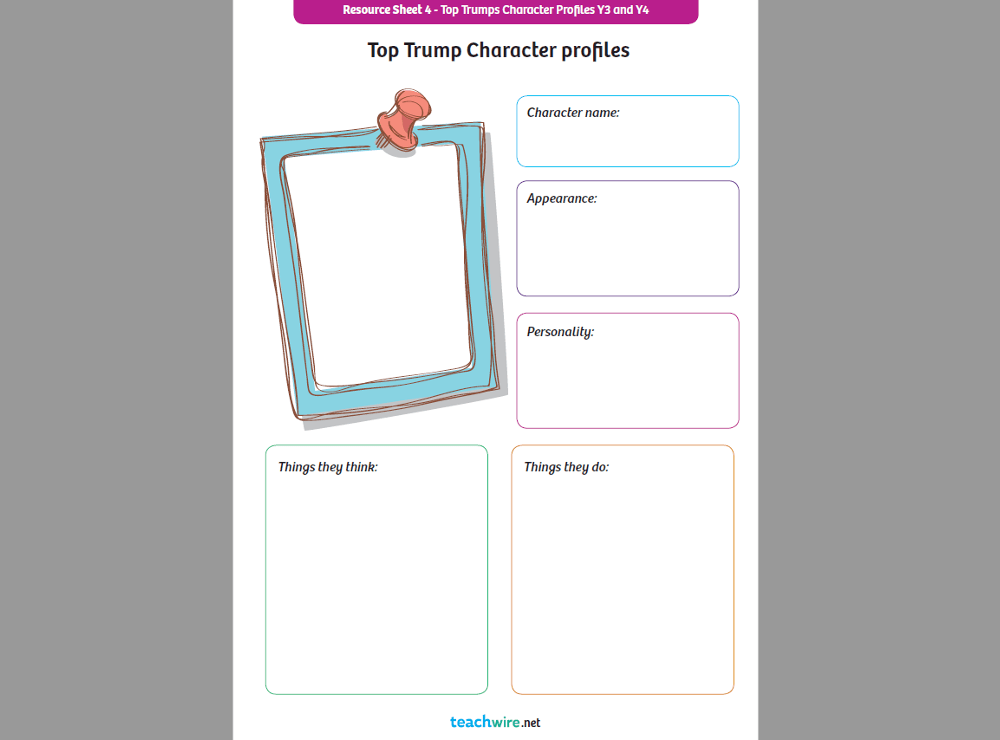

Top Trumps character creations

Creating characters using the popular Top Trumps format is a useful way to encourage pupils to think beyond the appearance of their characters and whether they’re adventurous, brave, cowardly or cruel, for example, and to consider their feelings, thoughts and motivations.

Using and punctuating direct speech is a significant objective for pupils in Lower KS2. So, by including space to plan what characters say, this Top Trumps character profile encourages pupils to include direct speech in their narratives and so create characters with physical presence beyond their appearance.

Once you’ve completed a planning profile with pupils, you can then model using it to write effective character descriptions, showing how to include aspects of character through descriptions of actions, thoughts and dialogue.

Write descriptions of imaginary people

Writing their own descriptions of imaginary people and aspects of their lives is a sure-fire way to get children’s heads spinning.

In this free KS2 lesson, children will draw on Moon People by John Dabell to inspire their own writing and create their own descriptions of moon people and moon life.

Create a character from the feet up

We’ve all heard the expression that you don’t know someone until you’ve walked a mile in their shoes, well here’s an exercise from First Story that’s designed to get to the soul of a character, by starting at the sole.

First, ask each student to take off a shoe and draw around their foot. Then, starting at the toe, ask them to create a fictional character in their mind and to imagine that character’s feet. What are the feet like? Big, small, calloused? Long toenails? What sort of shoes do they wear?

Next move up to imagine the character’s ankles. Are they strong? Weak? What about their knees? Do they have scars on their knees? Why? Carry on up the body with this activity.

Descriptosaurus character description games

This Descriptosaurus resource from National Literacy Trust was produced for a writing challenge and has all sorts of descriptive writing activities.

The one which we’re interested in here are the two character description games, which are supported by character cards (which you’ll find in the appendix of the resource).

These cards are arranged in levels from one to six, with the characters traits and vocabulary becoming progressively harder with each level.

Judy Moody character creation challenge

Another National Literacy Trust resource, this one is based on the Judy Moody series by Megan McDonald.

In the first book of the series, we get to know Judy through a homework task set in her new class – a ‘Me’ collage. As part of the collage, Judy has to think about some of the best, worst and funniest things that have ever happened to her.

These resources challenge your pupils to develop this idea and pen a 500-word short story about a character they have invented, recounting either the best thing, the worst thing or the funniest thing that has ever happened to their character.

Create characters with The BFG

Does someone’s appearance always match their personality? Use these Roald Dahl activity cards and lesson plan for KS1 or KS2 to discuss this with your class, and learn how to create interesting characters in your own story writing.

Using ‘show not tell’ to improve character descriptions

‘Show not tell’ makes for more impactful and effective writing – and Tim Roach has some great teaching strategies to help children put it into practice…

‘Show not tell’ is a common piece of advice we give to young writers. But what exactly does it mean? Is it really a better way to write? And if so, how can teachers go about the business of teaching it for the benefit of their pupils?

On one level, ‘show not tell’ is the distinction between what the Ancient Greeks called mimesis and diegesis: imitation and narration.

Mimesis is how the writer imitates what happens by representing the action through their writing. Conversely, stories told from the diegetic perspective offer an omnipotent narrator telling the audience what happens.

I liken this to an intrusive voiceover in a film. It suggests that the director is not confident their footage captured what the screenplay inferred, so they add narration retrospectively.

Although there will be some variation by the receiver, readers imagine a story through the eyes of the character they’re supposed to empathise with. Therefore, making a closer connection with that character is essential.

Inherently, it’s about representing the character’s reality by describing their behaviour; so that the way they act and what they say disclose details about what they think, rather than having the narrator clumsily announce their emotions.

Change the task

Description is a necessary part of storytelling, but it needs to be balanced. If there’s not enough, you’re likely to have new characters teleporting into scenes. If there’s too much, you end up reading a list of character’s entire wardrobe in minute detail.

And yet ‘describe this character’ is a writing task objective often set for children, as if a character description were an actual thing anyone would ever want to read, let alone write.

Instead, why not ask pupils to select and describe two to three details that might cast light on some aspect of that character’s life?

Trending

Similarly, ‘writing a setting description’ is a common task in English lessons. Wouldn’t it be better if there were a purpose? For example, seeing the setting through a character’s eyes, which in turn reveals something about them, or describing it in poetry to invoke a particular emotion.

If you want to describe an entrance to a cave, it’s clearly better to say that a character had to stoop to enter, rather than giving the exact dimensions.

As CS Lewis said: “Instead of telling us a thing was ‘terrible’, describe it so we’ll be terrified”.

Using film clips

When it comes to teaching, ‘show not tell’ is one area of writing in which I’d actively advocate the use of film clips. Analysing storytelling through the language of film will help children understand the power in where they direct the reader’s attention.

Show a short scene and pause it with each shot change. For example, in Jurassic Park (Spielberg’s adaptation, not Crichton’s original novel), Spielberg memorably signals the approach of the T-rex by the vibrations radiating across the surface of a glass of water.

He shows us the consequences of the approaching dinosaur – but not the creature itself. As viewers, we know what’s coming, but the film forces us to experience it as the characters do.

The right words

In primary writing, we often use the ‘five senses’ model to tune children into a piece of creative writing. One potential pitfall of this is that it can lead to formulaic description, listing all the things a character can see and hear, telling the reader everything about the scene before shifting to the plot.

In contrast, placing a character into a scene, and having them purposefully notice and interact with a few details not only brings the setting alive, but also – more importantly – the character.

Dialogue is another way to ‘show not tell’ – and don’t devalue the use of the word ‘said’. When pupils are encouraged to replace all the ‘saids’ in their story, they inevitably end up with a series of paired verbs with adverbs.

In doing so, they might think less of the actual lines of dialogue spoken by the characters and more about the artifice of telling us how they are said.

When using alternative words, modelling and dialogic talk will uncover misunderstandings that children often have about unfamiliar vocabulary.

Synonyms

While thesauruses are a necessity in the classroom, cross-referencing in a dictionary and teacher discussion about the suitability of apparent synonyms are essential.

Otherwise, their use can lead to flowery phrases that miss the point entirely, due to the varied range of nuances within a set of synonyms.

Clichéd words and phrases, particularly when representing emotions, are obvious places where a teacher can model how to show what a character is feeling instead of telling that he or she is happy or sad.

Zooming in on facial expressions and body language is a simple way to train pupils to think about how emotions manifest themselves through behaviour, whether conscious (she folded her arms) or unconscious (he bit his lip).

Finally, comparison is a wonderful way to add shades to writing, and it’s more effective to teach figurative and rhetorical devices like metaphor and simile with this purpose in mind.

Whilst poetry is an excellent vehicle for introducing the concept, what we really want to see is pupils using these descriptive tools across all their work.

5 great examples of ‘show not tell’ in children’s literature

- “Where’s Papa going with that ax?” said Fern to her mother as they were setting the table for breakfast. The opening line of Charlotte’s Web is perfect in its set-up. In one sentence, EB White shows us when we have stumbled into this scene, who is present, where they are and what happened immediately before, as well giving us a scintilla of what might happen next.

- You can find another fantastic opening in Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book. Although grisly, it is a masterclass in the careful reveal of small details within a horrific scene. Gaiman never signposts the action; he describes it in precise, unhurried sentences that disguise the assassin with deliberate ambiguity.

- Siobhan Dowd never spells out Ted’s Asperger syndrome in The London Eye Mystery, but the main character alludes to it in his self-aware, first-person narration (his “different operating system”), as do other characters through their dialogue.

- In Jakob Wegelius’s The Murderer’s Ape, the author hints at the nature of the protagonist, Sally Jones, with a solitary one-word clue – “fur” – in the prologue, before she reveals herself to be a gorilla.

- Letters from the Lighthouse by Emma Carroll introduces an antagonist – Esther Jenkins – and gives just two small points of description: her dark brown plaits (“sucked to a point”) and a voice that spoke English “a bit oddly”. The author doesn’t resolve this clue to her background until a hundred pages later.

Tim Roach is a Year 3 teacher based in Oldham.

Drama and story writing activities for developing characters

From annoying words and mannerisms to finding out what’s in someone’s bag, these innovative ideas from Leanne Welsh are great for delving deep into characters’ backstories…

A few years ago I attended a workshop that blew me away. It was Kat Burr’s All work and no play? Introducing new views and creative ways into plays.

In this workshop we gained fascinating insight into ways that we can help pupils to develop characters in plays. The ideas aren’t strictly limited to plays, however. They’re a worthwhile starting point for any creative writing and folio work.

What’s in my bag?

In this activity, a pupil chooses two items from a bag. The rest of the group/class then have to use these items to work out what the person’s ‘holes’ (flaws) might be. It’s important to tell pupils to think about the person with the items as a character, rather than as themselves. This is so nobody’s feelings get hurt in the process.

For example, if they select a small mirror from the bag, their flaw, as a character, might be that they care too much about their appearance and what people think of them. This immediately allows pupils to start to develop a character in their own head and what the person might be like.

If you don’t have a bag of items to hand, watch a YouTuber doing a ‘What’s in my bag?’ video. Pause it in between items and ask pupils to discuss or write down what their flaws might be because of their chosen items.

Killer lines

In this task, you give groups of pupils a number of lines from a play or novel (or ones that you’ve made up yourself). They have to work out what kind of character would say them. Baddies usually work well – we all know they get the best lines.

Provide images and see if pupils can match up lines with a character, giving a reason why they think they could say that.

For example, if you use the line, “Long live the king!”, some pupils might say Scar from Lion King because he’s desperate to become the king and get rid of his brother.

However, there may be another opportunity for an interesting discussion on ambiguity. Perhaps it depends on the way that a character says a line and the tone they use. Voice is so important in order to develop an accurate character. We have to hear them speak, right down to the laugh that they use.

This line could have been said by a bunch of servants who are loyal to their ruler, so even the status of the character is vital. Where is the character in terms of the food chain? Are they a boss or are they a disgruntled ex-employee looking for revenge?

An important lesson that emerges from this task is that the delivery of a line is often more important than the line itself.

Words that annoy you

Ask pupils to write down a word on a Post-it that makes their blood boil (or, at least, causes them some discomfort) when someone says it. To say my students loved this is an understatement. They were doing this as a group and looking at each other’s saying, “Ugh, I hate that too! Why do people do that?”.

Next, ask pupils to think about the mannerisms people use that annoy them. If you want a really successful task, ask about annoying things that teachers do (obviously telling them to keep it anonymous).

Each group will come away with loads of words and mannerisms. Ask them to explore how they think each of the annoying words would be said, and what the mannerisms would look like.

Think about what kind of character would suit each line. What personality would that character have? How would they interact with other people? How would their voice sound as they said it?

Next, ask them to think about the character’s backstory. What makes this person have this mannerism? Where did the use of a word come from? Did they start to use it when their status changed in society? Do they only use these words or mannerisms with certain people? Do they change depending on who they are around?

This task is really fascinating. It’s interesting to hear pupils saying, “Well they only say that to us because we’re a pupil, I bet they are different around the headteacher!”.

Anonymous comments

The final task, and one that I think is brilliant, is getting pupils to eavesdrop on a conversation. This could be at break, lunch or on their way home from school.

They should each take an anonymous comment that they find unusual or funny and bring it back to class. You can then explore these comments as a group, perhaps putting them all together to create a short sketch.

Pupils can even provide the lines that they think came before or would follow. It’s another interesting opportunity to explore voice.

Pupils often only have an image of a character in their head but it’s important to delve into the history of a character in order to explore what their strengths and flaws might be.

Leanne Welsh is an English teacher in Scotland.