Zone of proximal development example – Why it’s a two-way process

How a casual game of tennis led to some interesting thoughts around the zone of proximal development…

- by Aaron Swan

- English teacher since 2007 and writer

A tennis-themed zone of proximal development example leads teacher Aaron Swan to consider how teaching within students’ ZPD is a two-way process…

What is the zone of proximal development?

The ‘zone of proximal development’ is the range of difficulty that provides the best possibility for students to make progress.

The thinking goes that anything too hard will exceed their grasp of cognition to be of any use, while anything too easy won’t provide enough challenge.

I’ve always known this in theory – but recently, I saw it for real.

Zone of proximal development example

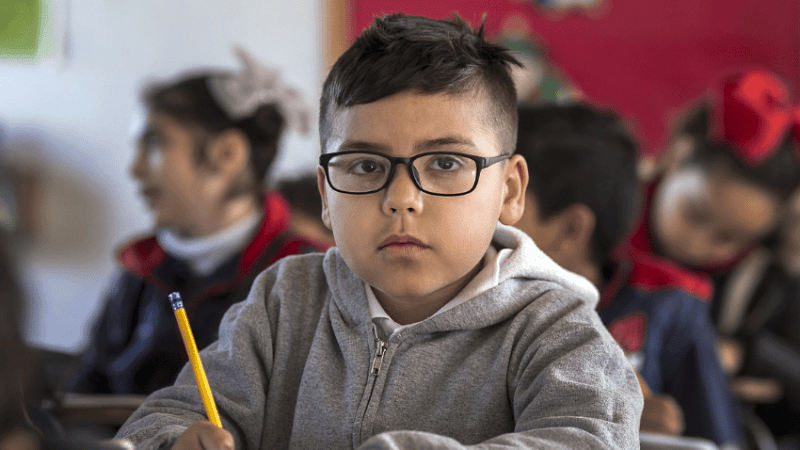

While playing tennis on our driveway with my 7-year-old daughter, I observed how she had the ability to return serves, so long as the tennis ball came to her within a fairly small area.

She could return it confidently from within this restricted range – but from anywhere outside it, her ability to return the ball dropped fast.

This ‘tennis ZPD’ turned out to be even smaller for my son, aged 5, who needed the ball served virtually to the strings of his racket.

I’ve seen similar physical zone of proximal development signs when playing catch with them, or kicking balls.

I could see my daughter’s confidence growing after only a short game of tennis. Something that aided her progress yet further was the process of adding minor variations – a few inches up or to the left, slightly harder or softer – to locate the boundaries of her zone of proximal development.

Increasing the speed of the routine made a big difference. I called “Serve, bounce, hit” to help with her timing, grabbed the ball and then repeated my call for her to focus her attention – gradually decreasing the time between repeats, while increasing the speed of the activity and her need for focus.

A teacher’s zone of proximal development

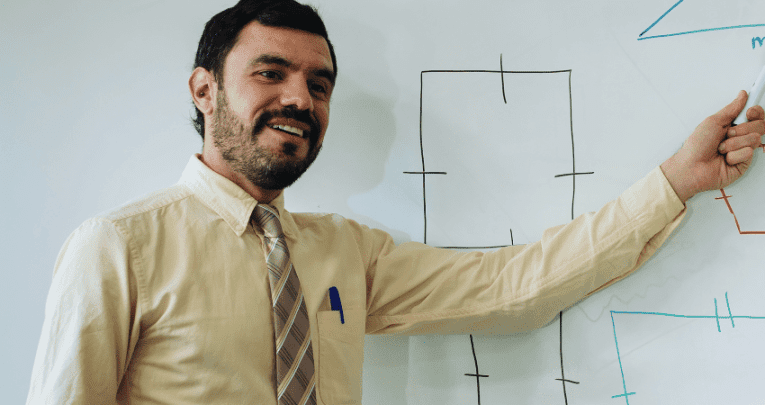

But, let’s be honest – the ‘variation’ of my serves wasn’t really in my control. My own inability caused the variations. Her ability to develop within her zone of proximal development was limited by my ability to serve the ball to her appropriately every time.

As we built up a rally, a decline in her returns to me was met by a decline in the accuracy of my own returns to her zone of proximal development.

Trending

My ZPD was far larger than hers, but this dual decline in our respective accuracy was exponential. This aspect of teaching cognitive subjects is one I feel worth highlighting – the teacher’s zone of proximal development.

Teachers routinely challenge students, who will ‘return’ some cognition back to their teacher. When we give students a cognitive task at the edges, or outside of their zone of proximal development, their returns will be wildly more variable. This makes it more difficult for the teacher to control in a way that brings the concept back to the child for successful reception.

A teacher might present a concept alongside an analogy. We could say that literature is like an engineered product, made up of many different components, each with its own name. Adjectives, for example, are modifiers – similar to how you can alter a car with different wheels and body kit.

Difficult volleys

Their ability to handle such an analogy can, however, create new problems for their cognition and cause their returns to become more erratic. “Literature isn’t made”; “Words aren’t cars”.

As the dialogue progresses, the variations in this cognition will exceed the teacher’s ability to send returns to students’ specific zone of proximal development.

They become tennis balls clipped through the air, which the teacher has to stretch to return with ever-increasing difficulty.

Efforts at resolving students’ misunderstandings are often beset with increases to cognitive load, rather than decreases. At this point, it’s perhaps wise to stop the rally and reset.

In a class of 30-odd students, their cognitive returns to the teacher will always be wildly varying. As such, knowing the best way of receiving and sending cognition back to them accurately, and with a good sense of timing, becomes incredibly difficult.

For that reason, it’s worth bearing in mind that when discussing zone of proximal development, we shouldn’t just focus on how it shows up in students, but also on how we observe it among teachers as well.

Aaron Swan is an English teacher and has been a head of department.