Talk partners – The what, the why and the how

Learn the most effective way to use this classroom staple, including important dos and don’ts, with this advice from Jack Dabell, education advisor at Tapestry…

- by Jack Dabell

- Education advisor at Tapestry and former primary teacher Visit website

You’ve probably heard about talk partners and may well have used this teaching strategy already.

However, because it’s a classroom staple, you may not have thought any more deeply than, “This is a good thing to do, I’ll add talk partners to the lesson plan.”

Let’s have a deeper look at talk partners as a teaching tool. What is it? Why should you use it? And most importantly, how should you use it?

What are talk partners?

Thankfully, “talk partners” is a fantastically self-explanatory term. It’s when children partner up (though it can be more than just two) and discuss a topic.

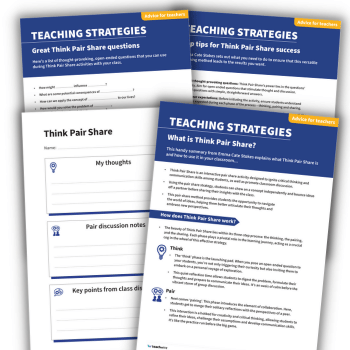

It’s sometimes called think pair share, because it’s often a three-stage process. First you pose a question or talking point. Secondly, children partner up and talk about it. Finally, some students share what they were discussing with the whole class.

Talk partners is a very quick technique that you might do multiple times in one lesson. You may want to specify a time limit for the talking section – 30 seconds to a couple of minutes is typical.

Use this strategy during your teacher input part of the lesson, or try it at another point when you think it would be beneficial.

Why is it a good strategy?

The success of talk partners is that it gets children involved and engaged in their learning – something most of us would agree is important in helping children to progress.

One of the biggest benefits when it comes to talk partners is building children’s confidence. Pupils who are less confident to speak in class can discuss their ideas with a peer. This helps them to articulate their thinking.

Even if that child isn’t the one to share the pair’s idea with the class, they still get the benefit of being more involved in the discussion.

Another benefit of talk partners is the increase in thinking time. You might fall into the trap of not giving enough time for this. Properly planning to use talk partners ensures more thinking time. This then lead to more articulate answers, which leads to better engagement for all.

“One of the biggest benefits when it comes to talk partners is building children’s confidence”

Another benefit of talk partners is the amazing opportunity it gives you and the other adults in the room to observe and listen to children doing something incredibly important: talking.

Challenges you may face

There are two main challenges that can arise with talk partners. First, the relationships between children. Partners can get stale, and some children don’t like talking to particular children.

One talk partner might be too dominant in the pair which negates some of the positive effects for the other. You need to monitor your talk partners as they work together. Their conversations should be balanced and constructive. If they aren’t, change them.

Secondly, how you choose to use talk partners can hinder more than it helps. For instance, you might plan to use the strategy at the wrong time or let the talking go on too long. These were both problems I encountered when I first started using the approach in the classroom.

Remember, talk partners are there to help children get involved. This means you may need to adapt the strategy for children who use non-verbal communication and/or children with additional support needs. You need to ensure that all children in your class benefit from some part of the process every time.

How to use talk partners

It’s very important to introduce talk partners correctly. Because it’s a common teaching technique, you might have a false sense that it’s already an embedded practice.

However, even if your class used talk partners with their previous teachers, you need to introduce and model how it works in your classroom.

The first time you want children to use talk partners, choose one of your more confident pupils and model it with them. Ask another child (or your TA) to pose a question to you. Then model a short discussion with your volunteer.

Focus on being clear, sticking to the point and listening to the other person – all the things you want the class to be doing.

Talk partner dos and don’ts

Do:

- Listen to the other person

- Make sure both people get a chance to say something

- Be respectful of other people’s ideas

Don’t:

- Look bored when the other person speaks

- Talk about something completely unrelated

- Let your partner do all the work

Choosing talk partners

Who goes with who is arguably the most important thing when it comes to using the talk partners strategy. There’s many different ways you can pair the children in your class – you know them best.

In my experience, and the experience of others, randomly generating talk partners and changing them often is a good strategy. (Although you may want to randomly generate these pairs after school so you can make small changes if necessary without prying eyes…)

In my classroom we changed talk partners every week. I recommend not keeping the same partners for more than two weeks.

Planning for talk partners

Once talk partners are picked, it’s time to plan. Planning when to use talk partners is more important than you realise. The best time to have children talk to their partners is after you pose an open-ended question. This is to incite more conversation and different interpretations.

Be clear with the children that there is no right or wrong answer. This helps to alleviate anxiety and promote discussion. When I started I found it helpful to include the times and questions in my lesson plan, but after a while it became more instinctive.

“Planning when to use talk partners is more important than you realise”

When planning your lesson, decide which key questions you’re going to ask and when these will be followed up by talk partners. In my experience, three times in a lesson is about right.

As for how long each instance takes, you want to keep the balance between maintaining the pace of your lesson and giving enough time for it to be valuable to the children. Try one minute for discussion and then two minutes to share with the class. Another tip is to put a timer on your board.

Sharing with the class

Children sharing their ideas with the class is just as important as chatting about them with their talk partner. There are a few different ways you can do this:

- Select a few talking partners to share their ideas with the whole class

- Randomly select pairs to share with the rest of their table (you can join a different table each time)

- Ask children to write their key points on a mini whiteboard and hold it up

However you do it, praise children who share. Fostering a healthy outlook on sharing ideas, and being respectful of others’ ideas, will do wonders for your classroom ethos.

Examples of praise

Speaking of praise, make sure it’s constructive and meaningful during every step (“well done” and “good listening” are neither).

Try: “Artem, I saw you were really listening to your talk partner while she was talking because you were looking at her and asking questions. Great work.”

Or: “Matias, I love how confidently you just spoke in front of the class. You and your partner worked hard in organising those thoughts.”

Talk partners can be one of the easiest and most useful tools you have as a teacher. Plan when to use them. Use open-ended questions. Change your talk partners often. Involve yourself in the discussions and praise, praise, praise.

Jack Dabell is education advisor at Tapestry, the online learning journal, and a former primary school teacher. He also writes for the Foundation Stage Forum.

Alternative to talk partners – listening partners

It’s time to start listening, say Nikki Gamble and Jo Castro…

The talk partners approach has become a familiar routine, where everyone plays their well-rehearsed part; but to what effect?

Trending

There is often little time given for these talk partner conversations as the teacher strives to maintain ‘pace’. The more confident child often dominates; both children talk at one another rather than listen; and the teacher frequently doesn’t know what has been said.

Focusing on talk means focusing on what we need to say, rather than developing a dialogue – a genuine exchange of ideas.

Listening partners

Imagine that we reframe this interaction, and instead of ‘talk partners’, we call them ‘listening partners’. Immediately, the focus changes from ‘tell your partner what you know’ to an opportunity to listen to what someone else knows or thinks, and how that fits our understanding or opinion.

By listening actively, we connect more deeply. We show that what others say matters to us, and we are happy to wait for them to think; we learn a new perspective, and consider whether we agree or disagree with it. Both partners grow from the experience.

Listening partners in action

This process works for any paired talk around a text. Julie’s Year 3 class is reading Joesph Coelho and Richard Johnson’s Our Tower.

They are discussing the details of the front cover. Julie has asked the children to work with a listening partner and assign themselves as either partner A or B.

The children have been given a set of questions or prompts for Partner A to ask Partner B:

- Where do you think this is?

- What do you notice about the children?

- Where do you think they are going?

- Where do you think they have come from?

- What do you think the yellow things are?

When they have finished, Julie gets Partner B to ask Partner A the same questions, listening carefully to their replies.

It’s tempting, as the teacher, to get involved with the children’s conversations. But instead, allow them the space while you use the opportunity to make informal assessments.

As the children share their ideas, you can observe, listen, and note insightful comments, particularly those that link to existing knowledge or present evidence of new learning.

Feedback

Typically, after talk partners, teachers ask children to share what they discussed with the class.

Julie makes some small adjustments to this process to avoid the children simply repeating what they have already talked about with their partner. This often slows the pace of the lesson and doesn’t advance the learning.

She gathers the class and shares a couple of her observations, making connections between the children’s ideas and presenting contrasts in their thinking.

This signals to the class that she is attentive and interested in what they say when talking in pairs or groups. In short, it models listening.

Sharing her observations also allows her to advance the learning, by selecting those points that move the conversation on.

It maintains a good pace in the lesson. Pace in this context doesn’t mean speed. It means maintaining the learning pace rather than letting it drift.

Finally, Julie encourages the children to reflect on what they have learned from each other:

- Did your partner say anything that surprised you?

- Did you have the same ideas as your partner, or were yours different?

Let me tell you

Another way to avoid show-and-tell is to switch up traditional talk partners by asking pupils to comment on each other’s work rather than explain their own.

A Year 5 class is reading The Promise by Nicola Davies, illustrated by Laura Carlin. The teacher, Karl, reads the opening sentences, which set the scene for the story.

He has withheld the illustrations. After a second reading, the children draw the pictures in their mind’s eye, visualising the setting.

When they have had time to complete the task, Karl asks the children to turn to their listening partners. As usual, they assign themselves as partner A or partner B.

Rather than show and explain their own ideas, they are going to explain what they understand about each other’s work.

So, partner A explains how they think partner B has interpreted the scene and vice versa. If partner A thinks partner B has misinterpreted their ideas or has omitted something important, they have an opportunity to clarify.

This small adjustment to the more typical ‘show and tell’ approach keeps both partners active and involved, setting the conditions for active listening.

Moving partners

Nazreen’s class are reading the Greenling by Levi Pinfold. They have been studying the book for three weeks and are at the end of the teaching sequence.

They are considering the statement, ‘Greenling is a disruptive influence.’

After clarifying what they understand by the word ‘disruptive’, Nazreen organises the class into two concentric circles.

The inner circle faces outwards so that each child faces a partner from the outer circle. Nazreen presents the statement and asks the children to discuss it with their partners.

For the first 15 seconds, partner A tells partner B their views and then the roles are switched. After 30 seconds, the inner circle moves to the left so the children have new partners.

This is repeated several times before Nazreen asks the inner circle to move around to the right – the children are now talking with a partner they have already spoken with.

In reflecting on the process with the class, Nazreen makes listening the focus: Tell me two new ideas that you learnt from different partners.

The strength of this approach is that the children carry with them ideas that they have heard expressed by different partners.

It particularly supports children with English as an additional language or special learning needs, allowing them to borrow ideas, practise language, and build understanding sequentially.

Nikki Gamble is the director of Just Imagine and provides consultancy and training in schools in the UK and internationally. Jo Castro is a consultant for Just Imagine and a leadership coach who works with teachers and senior leaders in schools.