Safeguarding in schools – Key principles every educator should know

What areas of safeguarding do you need to prioritise and what resources are there to help? Join us as we explore this vital issue…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

What areas should leaders prioritise?

Ann Marie Christian highlights the safeguarding developments and priorities that school leaders should heed this academic year…

Some years ago, safeguarding arrangements within schools became an important part of Ofsted’s inspection framework.

Part of my role involves visiting schools across the world and inland UK to carry out reviews and audits of schools’ safeguarding provision. This is a privileged position that enables me to notice a range of recurrent safeguarding themes and concerns. I’m going to share these with you here.

In 2015, Dr Carlene Firmin from University of Bedfordshire introduced the concept of ‘Contextual safeguarding’. The government eventually added ‘Risk outside the family home’ to its statutory Keeping Children safe in Education (KCSiE) guidance.

This meant that schools and colleges would now be expected to monitor risks in their local area and join families in supporting pupils’ safety accordingly.

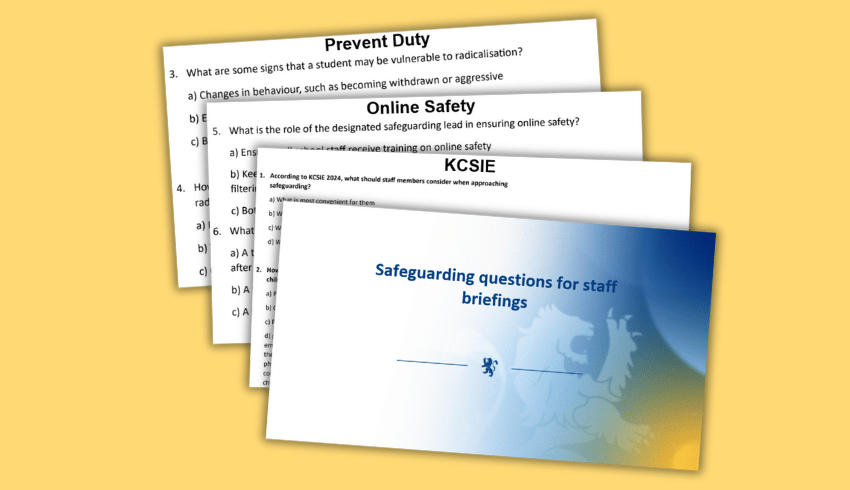

Safeguarding quiz

This free safeguarding quiz PowerPoint contains 128 slides of multiple-choice questions, ideal for staff briefings. Each set of 10-12 questions covers a mix of topics.

The upshot was that schools began to regularly liaise not just with parents on safeguarding matters, but also police authorities, local retailers, businesses and other local organisations.

Despite progress being made in the years since then, I’ve still seen first-hand how pupils will speak of worries regarding their journeys to school. They identify certain underpasses, alleyways and bus routes as being potentially dangerous.

School staff often won’t be aware of these concerns, especially those driving in each day from other villages and towns. Yet it remains the case that inspectors will routinely ask contextual safeguarding questions during inspections. This means school and college staff should be aware of nearby trouble spots and any action by local partnership agencies.

That’s why it’s vital to prepare recent case studies that demonstrate how your school has successfully protected children using the contextual safeguarding model.

Bullying and microaggressions

Next, child-on-child harm. Back in the pre-‘Everyone’s Invited’ world, the DfE published its first Sexual Violence and Harassment Guidance for Schools and Colleges in 2017. The DfE subsequently revised this in 2018 and 2021.

More recently, the guidance has been embedded in Part Five of the KCSiE 2022 guidance. It was expanded to include physical harm, sexual harm, neglect, emotional harm and harms stemming from child-on-child incidents. The latter, more commonly known as ‘bullying’, has been with us for many years, of course – but how often and how consistently are you currently recording such incidents?

Many pupils in school settings will frequently experience microaggressions. Pupils with protected characteristics will often experience them almost daily from peers, and even sometimes – if unintentionally – from school staff.

Pupils will frequently detail microaggressions they’ve experienced to trusted peers and chosen staff. When it’s fed back to staff, the nature of the microaggressions – especially racism – will be known to them already. But they may not necessarily know their short- and long-term impact or frequency.

Issues relating to gender, sexuality and LGBTQIA+ identity will commonly come up in this context and in discussions with senior leaders.

If you don’t already, reflect on the gendered pronouns we all use daily. Think about the impact this can have on pupils who may be non-binary or otherwise questioning their gender.

We can reduce harms by working to make the language we use more inclusive and welcoming to all. Have you, for instance, questioned the titles of ‘head girl’ and ‘head boy?’ Could you simply recognise your ‘head pupils’ instead?

I should also note that neurodiverse pupils are more likely to experience microaggressions than most. This is sometimes due to not understanding the intent of sarcasm directed at them. As a result they experience child-on-child harms.

Conduct, contact, content, commerce

It’s perhaps to be expected, yet still disappointing to see that sexism, racism, and homophobia all continue to be major safeguarding concerns.

With influencers like Andrew Tate and others effectively promoting hate crime on social media, the DfE has responded by updating its KSCiE guidance to include ‘four C’s’ that schools should teach through the curriculum.

These comprise ‘Conduct’, ‘Contact’, ‘Content’ and ‘Commerce’. These are intended to cover topics such as fake news; the sending and receiving of abusive or threatening messages; the production of inappropriate content and problem gambling, among others.

Another trend increasingly seen across schools is the adoption of discriminatory, and thus de facto unlawful uniform policies. I recently visited a Christian school where Muslim children could apply and the school would accept them on roll. However, they were not allowed to wear their hijab at school. Staff could wear them – but not students.

We also continue to see huge misunderstandings when the basic physical properties of textured, curly and afro hair conflict with schools’ expectations around students’ personal appearance and hair styling. I’m aware of one boarding school that told a student his Afro was too high. Are there any schools telling children with ‘European hair’ to cut it because it’s too long?

Finally, a relatively recent consideration for schools are the arrangements around changing rooms, boarding houses, toilets and dormitories on residential trips, and whether we need to adapt these to support transgender and non-binary pupils. It’s important to bear in mind that the legal safeguarding framework requires schools to protect the welfare of every child.

Too much responsibility?

This brings us to matters of safeguarding governance, and the failures caused when schools appoint individuals lacking adequate expertise and preparation to the ‘link governor’ role responsible for safeguarding.

Some chairs have consequently opted to take on the link governor role themselves, in addition to their existing duties. Both roles are essential, but together, they entail a huge amount of responsibility for one person.

Trending

Given the importance of safeguarding in school inspections, we can perhaps excuse this move if schools enact it as a strictly temporary arrangement, but not if they intend it as a long-term solution.

Best practice in this area would see the formation of dedicated safeguarding subcommittees. These would be responsible for scrutinising all safeguarding expectations. This is everything from being vigilant around issues such as female genital mutilation, to managing their school’s Prevent duties and implementing safe recruitment policies.

Joint working between a school’s HR team and the Designated Safeguarding Lead is essential for getting recruitment right. In 2014, the government removed specific training expectations and renewal dates concerning safer recruitment practices from the KCSiE guidance. This led to a noticeable deterioration in knowledge and updates in this area thereafter. Things get more complicated still when the HR team of a local authority is working to different standards than the centralised HT teams of nearby MATs.

More recently, it’s the case that many schools and colleges are still yet to fully complete their required online safer recruitment training. Yet they’ll boast about their latest training attendance figures.

Needless to say, when it comes to light that they’re unaware of statutory safeguarding changes made since 2020, things start to get awkward…

A question of trust

Last of all, let’s talk about agency-sourced catering, cleaning and supply staff. Schools typically trust their agencies to follow robust recruitment practices, but will rarely be aware of the relevant details.

Have people at the relevant agencies attended safer recruitment training within the last three years? Can they produce any certification? Does the agency bring up any safeguarding questions during face-to-face interviews? Have they had sight of their workers’ DBS certificates?

School staff will often assume that agency workers have received safeguarding training within the last 12 months. But how do they know for sure? How many agency staff have actually read the latest KCSiE guidance and signed to confirm they understand it?

Is your safeguarding provision up to date?

- Read the latest KCSiE guidance from front to back. Highlight any changes you see compared to previous revisions and when/how you will enact these

- Ensure key staff have attended credible safer recruitment training. Firmly embed the 2020 changes within your recruitment processes

- Visit the Contextual Safeguarding website to complete a mapping exercise concerning nearby locations where students feel unsafe

- Carry out a pupil survey asking them about child-on-child harms (whether emotional, physical, neglectful and/or sexual in nature). This will help you better understand their lived experience

Ann Marie Christian is a safeguarding and child protection expert; for more information, visit annmariechristian.com. Browse resources for Child Safety Week.

Using technology to strengthen your school safeguarding

Safeguarding and technology are deeply interconnected. By keeping strategies straightforward and focused, you can help to ensure that technology enhances your school’s safeguarding mission…

Set clear policies and procedures

It takes everyone in a school to keep children safe, which is why clear safeguarding policies and procedures matter.

Schools should avoid vague or confusing language in shaping safeguarding guidelines. A simple statement of a school’s commitment to protect all children online can underpin everything else – including clear instructions on how teachers should report safeguarding concerns, gather key details and contact parents.

This will help to ensure you manage issues confidently and consistently right across the school.

Establish robust systems for safeguarding support

Technology can be a powerful safeguarding tool in schools, but the systems teachers use must be set up to prevent children who may be at risk from slipping through the cracks.

Software that flags unexplained absences in real time will help teachers identify any safeguarding concerns and respond to them quickly – but if a system automatically generates alerts throughout the day when a child is off school ill, it can distract the teacher from spotting genuine issues requiring immediate attention.

Engage partners

When you have a child who is being bullied online it’s not always easy to know how to help. But teachers aren’t on their own when it comes to keeping children safe.

The relationships between schools and parents can be a firm foundation from which to start addressing issues together.

With support from both home and school, it’s easier to spot signs of social withdrawal, anxiety or declining academic performance that may indicate a child is struggling.

Schools concerned about cyberbullying can also partner with local charities specialising in teaching young people about online safety and mental health. School staff can then keep their focus on the safe use of tech for learning.

Regular training

Not every teacher has the technical knowledge and skills to keep sensitive data on young people safe. Regular training can help staff use the tools they have access to more effectively, in line with broader safeguarding policies.

Teachers need to know how to use their own mobile devices to access and share student data securely, for example.

A regular course aimed at keeping their skills up-to-date could help them work more efficiently, without putting sensitive data at risk.

The right CPD will give teachers more confidence to explore the exciting digital tools available to enhance their teaching.

Matt Tiplin is a former school senior leader and Ofsted inspector, and currently VP of ONVU Learning.