School exclusion – how to support SEND pupils in primary

Persistent absence, suspension and school exclusion are more common among pupils with SEND, so what can we do about it?

I first met Jack when he was seven: he loved Star Wars and tigers. He was excellent at maths and had a wicked sense of humour. He was an intelligent, endearing and kind boy who was incredibly loyal to his friends and family. And yet, Jack was close to school exclusion due to his frequent, violent meltdowns.

He attended a small, village school, known for being excellent at inclusion.

They had a fantastic SENCO, who called me in tears. She didn’t want to suspend this bright but vulnerable boy.

The SENCO knew that SEND children are six times more likely to face school exclusion than typical peers.

She didn’t want Jack, an autistic, ADHD child with a Pathological Demand Avoidant (PDA) profile to become another statistic.

I was an advisory teacher at the time for the Advisory Teaching Service.

During the four-and-a-half years that I worked for the service, increasing amounts of time was spent reducing the number of school exclusions.

We were seeing high numbers of schools unable to cope with behaviours of concern – arising from dysregulated SEND children – who weren’t getting the right support.

I also began seeing an increase in persistent absence (PA), sometimes falsely described as ‘school refusal’.

Persistent absence

In truth, this is exclusion by a different name. The rise in PA is a national problem. Although figures vary from year to year, amongst this cohort again, the DFE suggest that 56 per cent have an identified SEND.

Data from Not Fine in School indicates that a further 43 per cent have unidentified SEND needs.

From experience, I know that all the children I have supported to reintegrate into school after PA were neurodivergent (ND). They were mostly autistic or ADHD, but several were dyslexic, dyspraxic or had a variety of ND needs.

Teachers agree that the best place for a child to be is in school. We can’t help them if they don’t attend, and yet, over the last decade the number of children excluded from education, whether due to behaviours that challenge, or emotionally based school absence (EBSA), has increased.

During my time at the Advisory Teacher Service and then as a SENCO in a small specialist school supporting children with EBSA, I developed the following strategies to help support SEND pupils back to full attendance. I still use these now to give intensive support to schools.

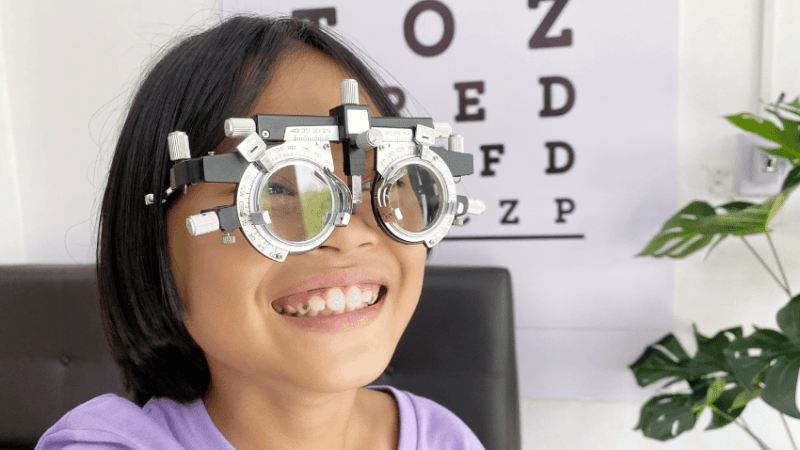

Different types of stress response

Meltdown and shutdown are two forms stress response that can end in school exclusion.

The school system currently views these two types of behaviour differently, although both can result in attendance issues.

Schools often see frequent meltdowns as behaviour challenges. Settings often feel they have no choice but to exclude the child.

They often view shutdowns, however, quite differently. These can be the result of burnout, which may lead to a child becoming an anxious non-attender.

Both these issues are behaviour-based forms of school exclusion and are more prevalent for SEND children.

It’s important to recognise that the causes of behaviours of concern are likely one of the three stress responses, known as fight, flight or freeze.

Stress dysregulation

We should understand that the dysregulation exhibited by both children close to school exclusion, and those with regular PA (defined as missing more than 11 per cent of sessions in a measurable period) are triggered by stress.

Neurodivergent children are likely to have higher levels of stress, for neurological reasons, and because the world is designed for neurotypicals.

In our classrooms, we tend to focus on children who, like Jack, frequently meltdown.

This is because that kind of explosion can be deeply upsetting for us and for the child.

Meltdowns demand our immediate attention and often send us into a stress response of our own. Sometimes we feel compelled to act.

However, other forms of stress response, such as flight risks, can be equally concerning.

For example, if Kasper, our ADHD/ dyslexic learner, is constantly running away, we may be (rightly) focused on his health and safety. In taking this action, Kasper is also excluding himself.

It’s understandable, too, that we may miss Mabel, our lovely, polite, dyslexic and dyspraxic pupil who is fawning to mask the freeze mode in which she finds herself.

Yet she will not be able to mask indefinitely. When the mask slips, she may no longer be able to attend school.

What Jack, Kasper and Mabel all have in common, apart from their neurodivergence, is their stress.

If we do what we can do help them regulate and lower the stress, this will mitigate behaviours of concern.

Our response must be bespoke, but using sensory, calming activities often gets good results.

Teacher stress

Teachers are time and resource poor. We love the kids! That’s why we play this game, but it’s tough working with dysregulated children. Stressful and tough.

When we are stressed, it’s difficult to be curious, which means it’s hard to find a new way of doing things. This is especially true if the child’s behaviour causes emotional contagion and compassion fatigue.

You can’t always have the answers. It’s best to ask someone with a fresh pair of eyes to help you look at the situation.

This could be a colleague from your school, or another setting. It could be an advisor from the MAT or LA. Either way, it may help you gain perspective.

Relational practice

Here is where your relational practice comes in: what do you know about your pupil? What do you know about their family/ home life? What are their special interests and how can you use them to motivate the child?

Even if you are certain that you know the answers to all these questions, it’s worth reviewing, especially if these has been a sudden, dramatic change in behaviour.

Really get to know the family, if you can, too. Parents and carers are often accused of being in cahoots with their dysregulated child.

The 2020 survey by the charity Autism UK, showed 87 per cent of schools believed that PA was down to issues with the parent or family.

Conversely, 91 per cent of families believed their child’s school-based anxiety was caused by mental health, sensory needs or was triggered by bullying.

Although this represented a few hundred parents, whose children only fell into one category of SEND, it goes some way to illustrating that there is a mismatch between what schools and parents see as the root cause of the issues, making it harder for these key players to work together.

Work together

Act together with the child, their family and key professionals to form a plan.

A risk assessment is a great place to start, but a consistent behaviour support plan can be highly effective.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach. You are likely to need to employ a variety of strategies over an extended period to see real and sustained change, but it can happen.

With consistency and perseverance, you can help to reduce stress for Jack, Kasper, and Mabel so that they’re able to fully attend school, without exhibiting behaviours of concern.

Catrina Lowri is a former SENCO, and founder of Neuroteachers, which helps educational settings work with their autistic and neurodivergent learners to find simple solutions for inclusive practice. Follow Catrina on Twitter @neuroteachers and learn more at neuroteachers.com