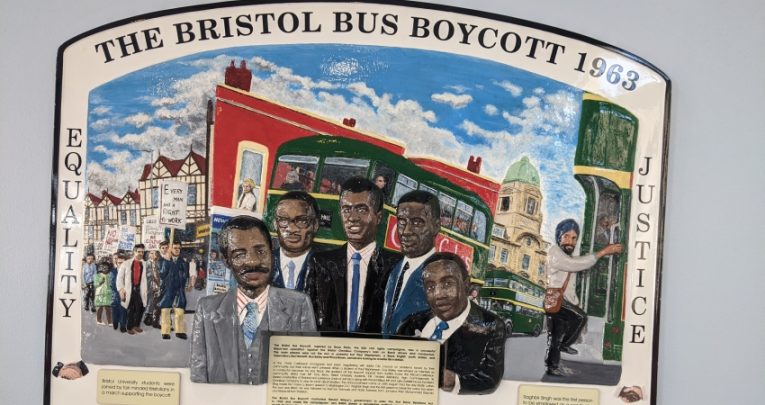

Social history – What students can learn from the Bristol Bus Boycott

Aneira Roose-McClew considers Roy Hackett’s legacy in showing educators and students how to stand up for democracy

The recent passing of civil rights activist Roy Hackett has shone a spotlight on the Bristol Bus Boycott and its legacy.

Hackett, one of the lead organisers, was driven to challenge the Bristol Bus Company’s unofficial ‘colour bar’, which prevented Black and Asian people from working as conductors and drivers, when his wife Ena was denied a job with the company in 1962. The ‘colour bar’ was a clear example of the discrimination faced by Black Bristolians – many of whom, like Hackett, had come from the West Indies after the British Nationality Act of 1948 naturalised all Commonwealth citizens, giving them the right to live and work in the UK.

Despite this legal right and the encouragement of the British government (which sought migration from British colonies to help the UK’s post-WWII economic recovery), those opting to make the UK their home faced hostility and discrimination.

Ena Hackett’s rejection from the Bristol Omnibus Company, despite her meeting the role’s requirements and there being vacancies available, compelled Roy Hackett to act. In response to this specific injustice and the many more affecting the daily lives of Black Bristolians, he united with other young Black activists and formed the West Indian Development Council (WIDC) to fight for their civil rights.

By 1963, others had joined the WIDC and a plan had been hatched – to publicise the Bristol Bus Company’s ‘colour bar’ and stage a boycott of Bristol’s buses, following in the footsteps of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The Bristol Bus Boycott was incredibly successful, not only ending the ‘colour bar’, but also laying the foundations for the passing of Race Relations Act 1965 (and later acts superseding it).

The Boycott’s organisers succeeded in their fight against racial injustice, despite being denied power on account of their race. Their story is one of hope that can galvanise students to challenge social problems themselves, and help shape a fairer, more just society.

Historical change-makers

In a survey we commissioned last year, we found that 93% of young people believe it’s important to challenge prejudice or discrimination when they see it happening. Yet despite understanding this need, young people feel that they lack the tools to do so, with 69% of those surveyed believing they’re not taught enough about how to stand up against, or deal with prejudice and discrimination in school.

Teaching students about the stories of historical change-makers can help address this deficit, giving them ideas on how they can assume individual and collective agency. Such examples act as models for hhttp://bit.ly/ts116-bbbope, while countering apathy and defeatism in the face of daunting social ills. Hackett and his fellow organisers used simple strategies that remain available to us all.

Trending

In our lesson ‘Protesting Discrimination in Bristol’, we teach students about the history of the boycott, but also introduce those strategies. Students explore the ‘levers of power’ – organisations or people upon which change-makers can apply pressure to amplify their impact – that were used by the Boycott’s organisers. They included both local and national government, the media and local industry, as well as schools and other education institutions.

Schools continue to shoulder the responsibility of preparing students to engage emotionally and ethically – not just intellectually – with the world around them. Platforming the stories of British activists like Roy Hackett who fought against injustice is vital, both for the health of society and for protecting the rights of all the individuals within it.

Civil liberties, and the right to live free from discrimination, are not a given. Many groups are still oppressed in the UK and around the world. History shows us that once-protected groups can lose rights they take for granted following the actions of draconian or authoritarian regimes.

Learning about strategies for standing up against oppression and ending social ills not only helps us create a fairer society – it also protects our democracy. As the Holocaust survivor Marian Turski once noted, ‘Democracy hinges on

the rights of minorities being protected’.

Aneira Roose-McClew is a former secondary teacher, examiner and teacher trainer, now senior curriculum developer at Facing History & Ourselves UK; for more information, visit facinghistory.org/uk or follow @FacingHistoryUK

Creative Commons attribution for main image – Jack Whittaker