Assessment for learning – Transformative teaching strategies to try

Revolutionise teaching and learning in your classroom with these expert assessment for learning strategies…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Unlock the secrets to effective teaching with our guide to assessment for learning strategies…

- What is assessment for learning?

- Assessment for learning strategies and techniques

- Assessment for learning examples

- ‘Assessment of’ vs ‘assessment for’ vs ‘assessment as’

- What counts as assessment for learning?

- How to tell if your assessment for learning strategies are working

- More assessment for learning resources

What is assessment for learning?

Assessment for learning – sometimes known as formative assessment or responsive teaching – is an approach whereby you use assessments to:

- provide feedback to students

- adjust your teaching strategies

This supports student learning and improvement, rather than merely evaluating their performance. Assessment for learning involves continually monitoring student progress and understanding to inform your teaching and empower students to take ownership of their learning journey.

To be effective responsive teachers, we need strategies to:

- explore children’s prior knowledge before starting a topic

- monitor how well they understand new content during teaching, so we know whether they are ready to move on

- assess understanding at the end of a lesson, so we can adjust our plans for the next lesson if necessary

Effective embedding

When Dylan Wiliam and Paul Black publicised assessment for learning in the 1990s, policymakers seized on it and rolled it out in schools. (Although there is some debate about how effective that roll-out was.)

How close is this definition of assessment for learning to reality in your school? Which elements do you embed effectively, and which do you need to revisit?

Teachers typically comment on the fact that a lot of time is devoted to the ‘seeking’ of assessment data but less to the crucial ‘reflecting and responding’ to that information.

Many schools have developed assessment ‘habits’ and routines. Whilst some of these are productive, others are simply not helpful. They tend to be founded on assumptions about what Ofsted, senior leaders or other stakeholders may be expecting.

“Many schools have developed assessment ‘habits’ and routines”

Try the following assessment for learning strategies in your classroom to get back on track.

Assessment for learning strategies and techniques

Vary your assessment diet

What is the overall assessment ‘diet’ like in your classroom and within your school? Has the culture of book scrutinies limited the range of assessment tasks because staff are overly focused on what makes for good ‘evidence’ of pupil progress?

Try providing more opportunities for carefully orchestrated choice and challenge by expanding the range of assessment tasks. Beyond formal tasks and tests, are there enough creative and diverse opportunities for all your learners to demonstrate what they are capable of?

If we restrict learners to a diet of standard exam-style questions and ‘neat notes in best books’ this is very limiting, not to mention boring. By asking students to present their learning in a new way we can begin to see shades of understanding.

For example, ask them for a metaphor: “If this topic/ idea were an object it would be a …… because….”. Pupils can also represent their learning in the form of models, word clouds, infographics, mindmaps, poems, etc.

Rich tasks of this type lend themselves to extended homework projects. They tend to generate fantastic resources for classroom displays as well as opportunities for presentations by the learners.

Anticipate misconceptions

As teachers, we know what the knottiest, most difficult aspects of the subject are. By planning with these at the forefront of our minds, we can be much more strategic and ready to offer appropriate support.

Try using techniques such as the GAS (Go and Stand) question to tease out exactly where misconceptions lie. Pose a question and place four different answers, one in each corner of the classroom. Ensure that only one is correct, and that the other three are each wrong in a different way.

Invite learners to stand next to the answer that seems correct to them, with the expectation that you may ask them to explain their thinking. Where learners have opted for an incorrect answer, you can see exactly which misconception they have and tailor support accordingly.

Be responsive

Consider how ‘responsive’ your learning environments are currently. Is there capacity to regroup students easily? Can you work with smaller groups within your classroom?

Try introducing mechanisms that allow you, the teacher and lead pedagogue, to work more closely with the learners who need you the most. Try assembling a few spare seats around your desk. Routinely invite learners to ‘come into a conference’ with you, thus allowing you to target your support more efficiently.

Use learning objectives to challenge and intrigue

The habit of simply telling learners the learning objective at the start of the lesson or, worse still, asking them to copy this from the board, requires no active, metacognitive engagement from the learners.

Such practices kill any sense of anticipation. They appear to be driven by the expectation that observers in the lesson would expect to see an objective displayed prominently at all times.

Try using the learning objective as a tool to explicitly challenge and intrigue your learners. Ensure that the objective is sufficiently challenging (if in doubt, tweak the verb to focus on higher-order skills).

Next, explore this with learners, perhaps using a “fascinator” (picture/prop/stimulus) from which learners predict the objective. Or try the ‘sneak delete’ strategy. This is where you gradually delete the objective one word at a time. Challenge learners to remember what was there previously.

“Try using the learning objective as a tool to explicitly challenge and intrigue your learners”

These engaging strategies help to keep the objectives live and ‘simmering’ throughout your lesson plans. They also provide a reference point for learners to reflect upon and discuss their progress at any given moment.

Another way to ensure a learning objective is valuable and focused is by presenting it as a series of questions. For example, you can introduce a lesson by saying, “Here are three questions that you won’t be able to fully answer at present, but you will be able to answer them by the end of the lesson.”

While this may not appear significant, it is quite a sophisticated strategy because it shares the learning, identifies the progress needed and identifies the success by which the lesson can be judged.

It often makes sense to start a lesson with a ‘big question’ to engage the students in an idea, with the learning intention introduced later.

Co-construct success criteria with learners

Pre-prepared, tick list success criteria are prevalent but problematic. They solicit little from learners in terms of engagement or cognition. As tempting as it may be for busy teachers to generate these kind of rubrics in advance, resist the urge.

Co-constructing success criteria with learners strengthens their understanding and helps to activate them as owners of their own learning.

Explore the features of quality work by playing WAGOLL (What A Good One Looks Like) bingo. Ask your learners to predict what a good example might look like and then to list up to six criteria in a grid.

“Co-constructing success criteria with learners strengthens their understanding”

As the WAGOLL is revealed, learners interrogate this exemplar whilst crossing off their correct guesses, thus strengthening their understanding of what is required in their own work.

Different examples

Helping students understand what good writing looks like is best done by giving them examples at different levels of quality, rather than written descriptions, since the words teachers use often do not mean to students what they mean to teachers.

It’s also important that the examples we give students are felt to be achievable. If the standard is too high, students may give up in the belief that such work is beyond them.

To many pupils, it can come as a surprise that they should take ownership of their learning. Another way to get this message across is this simple exercise:

- Ask students to draw a house

- Ask them to give themselves a mark or grade for the house

- Get pupils to swap their work with a partner

- Show a marking scheme that gives points for the various components for a house in the Philippines that is designed from sustainable materials and built to increase ventilation in a tropical environment.

The point of the exercise is to illustrate that we all carry around in our head what we think is the correct answer to a question, even when we don’t fully understand the question. Understanding the criteria by which we are assessed is really important

Make sure your questioning is effective

It is estimated that the average teacher asks between 300 and 400 questions every day of their working lives. We know that effective classroom discussion and questioning are essential components of formative assessment.

“To many pupils, it can come as a surprise that they should take ownership of their learning”

Troublingly, the wait time after questions is still thought generally to be less than three seconds. Effective questioning, with increased teacher wait time and a ‘no hands up’ culture, plays a crucial role in ascertaining the gaps in learners’ understanding.

Try Rally Robin (verbal tennis) or other Kagan collaborative learning strategies to re-energise learners and to provide significant time for oral rehearsal prior to selecting a pupil to answer questions.

We ask questions to determine what our students have learned, but in most classrooms, the answers come from the confident students.

The problem with this is that hearing from the same few willing volunteers gives the teacher very little insight into what is happening in the minds of the other students.

A policy of selecting students at random to answer questions will avoid the problem of hearing only from ‘the usual suspects’ – but even then, you’ll have little idea about what most of the students are thinking.

To get a better idea of the learning of the whole class, use an ‘all-student response system’. Simple systems such as mini whiteboards or ‘finger voting’ (where students hold up one finger for A, two for B, three for C and four for D) work well.

Once you’ve scanned the whiteboards or the finger-votes, you can decide what to do to best meet students’ learning needs.

Asking questions that require pupils to justify their responses – either written or verbal – is also important for eliciting misunderstandings. You can then respond to any misconceptions in this lesson or the next, withholding the correct answer so that students can learn what it is through a new exploration of the material.

Use hinge questions

Dylan Wiliam introduced the idea of the ‘hinge question’ – a good strategy to use during a lesson to establish whether all children understand the lesson so far, or whether some might need further explanation or support.

These often take the form of a multiple-choice question, because this is a quick and efficient way to gather the information on what every child thinks.

By establishing an expectation that every child must show the teacher their answer to the question – whether that be by holding up a mini-whiteboard, A/B/C/D cards, fingers etc – a culture of ‘no opting out’ is created.

You can then easily see whether all, some, or none of the pupils are on track with the learning. This is more effective than a ‘hands up’ approach, in which you may only find out what one or two children are thinking.

Crucial to success is that the hinge question is carefully thought out in advance, so that the wrong answers tell you something useful – revealing any common misconceptions or specific misunderstandings.

This helps you to know where to go next in your teaching. You could, for example, establish whether children have understood the difference between perimeter and area by asking them whether the perimeter of a 4cm by 3cm rectangle is A) 14cm or B) 12cm, etc.

Strategies like the hinge question allow the teacher to make ‘in the moment’ decisions about how to proceed. Are some children ready to move onto some independent learning, whilst others require further explanation or scaffolding?

Mark less

Teachers are still investing massive amounts of time and energy into marking that has negligible impact. In an effort to tackle teacher workload, some schools are now making bold moves towards a culture of active feedback with no written comments. How engaged are your learners with the feedback you currently provide?

Try enticing learners to care more about feedback by turning it into a ‘code cracking’ exercise requiring teachers to use coloured dots instead of written comments.

Make it personal

Self-assessment is central to assessment for learning. While it is a fairly straightforward concept, getting pupils familiar with what they should be self-assessing against isn’t always so straightforward.

One very simple idea is to use personal named placemats. These are ideally A3 laminated sheets that contain the assessment rubric (and additional spaces), which have either been developed internally or produced by the exam board.

Trending

“How engaged are your learners with the feedback you currently provide?”

Because these are personal placemats they can be placed in front of students at the start of each lesson, allowing them to become increasingly familiar with the criteria against which they are assessing themselves.

Use multiple-choice quizzes

To ensure these are meaningful you need to design them so that each possible answer is plausible and so you can use the quiz to elicit any erroneous understandings (see planning for possible misconceptions, above).

Ask pupils to share answers via hands, mini whiteboards or where technology allows, an online platform such as Kahoot. The latter has the benefit of self-marking, providing instant feedback to students and immediate opportunities for re-teaching or clarification.

Some platforms will provide a ‘post-quiz’ report for you to analyse, too. Learners need to feel comfortable at ‘having a go’ without the risk of being judged by others. Reassure them that this is genuinely a diagnostic learning tool, not an additional competition or ‘ranking’.

Use exit tickets

Exit tickets can be an effective strategy for an end-of-lesson activity. Design them to ensure they cover the key knowledge points of the lesson (usually linked to your learning goals or objectives).

They should provide an insight into the varying learning responses, including gauging any misunderstandings. General questions such as ‘Do you understand…’ are unlikely to be as effective. Use open questions on taught content or try a multiple-choice format.

Use retrieval practice

Constantly look for opportunities for retrieval practice and assessing prior knowledge and understanding.

You can structure exit tickets as ‘two-part’ – the opportunity to answer a question from both this lesson and a revision question.

The constant re-visiting of content is essential for consolidating knowledge and understanding – the oft-quoted expression ‘practice makes perfect’ pedagogically does hold some legitimacy!

Diagnostically, retrieval practice also allows you to maintain an understanding of students’ recall of prior knowledge, necessary in your curriculum sequencing, and learn where you might need to revisit content before introducing new material.

Get group work right

There is now a substantial body of research that shows collaborative or cooperative learning can considerably improve student learning. The problem here is that the same research shows that collaborative learning is rather hard to get right.

Two conditions are particularly important. The first is that students have to be working as a group, rather than just in a group. The second condition is that students have to be mutually interdependent.

In other words, the group work has to be set up in such a way that the best efforts of every student are necessary for the group to succeed.

Typically, we set up group work in such a way that two or three members of the group can do all the work, in which case the benefits of collaborative learning are lost.

Ensuring that both of these conditions (and especially the second) are met takes time, and considerable teacher skill – but once students realise that no one in the group can be successful unless everyone in the group is successful, student motivation will be increased, lower achievers will get more support, and high achievers will be forced to deepen their thinking when helping others.

Assign pupil-teachers

A natural extension to pupils taking responsibility for their own learning is for them to take responsibility for others’ learning.

A simple strategy is as follows:

- Prior to a lesson, identify pupils (four or five) to act as pupil-teachers.

- Give the pupil-teachers some key instructions about their role and what they need to do. This can be before the lesson, using a TA to pass on the information, or via written instructions.

- Give the pupil-teachers a badge or lanyard to identify them.

- Share the ground rules for pupil-teachers with the whole class. For example, they are there to promote learning – they can’t give out detentions or go into the staffroom!

- The pupil-teachers will work in groups asking pre-planned questions (from you), leading on an episode of learning, emphasising the shared criteria etc.

- Debrief pupil-teachers at the end and use it as a source of feedback – what went well and what could be improved?

Compare against previous work

For self-assessment to be useful, it needs to be anchored so that students know what it means to understand something, and this is not always easy.

Rather than anchoring against external criteria, it can be particularly helpful for students to compare their work with their own previous work in the same area.

By getting students to avoid comparison with other students and instead examine whether their current work represents a personal best, students will see that however they compare with others, they themselves are making progress.

They will see that, as Jeffrey Howard says, “Smart is not something you just are, smart is something you can get”.

Know when to push and when to back off

As teachers we’re told that effective feedback should be descriptive rather than evaluative, and this may be good advice much of the time. But there are also times when it is helpful for students to know exactly how they are doing.

We’re also told to be positive rather than critical, but sometimes it is more important to point out things that are going wrong.

The real issue here is what the student does with the feedback. As every teacher knows, giving the same feedback to two similar children can produce different results. It may cause one child to strive harder, and the other to give up.

“Sometimes it is more important to point out things that are going wrong”

We need to know our students and know when to push, and when to back off. And students need to trust us to have their best interests at heart and to know what we’re talking about.

Ultimately, good feedback is any feedback that gets students doing more of what we want them to do – and the most important factor here is the relationship between the students and the teacher. Get that right, and everything else is relatively unimportant.

Thank you to the following writers for their contributions.

Claire Gadsby is a freelance education consultant, trainer, keynote speaker and author of Perfect Assessment for Learning (Independent Thinking Press).

David Spendlove is professor of education and director of teaching and learning at the University of Manchester and an expert in AfL, research and teaching methods. He is the author of 100 Ideas for Secondary Teachers: Assessment for Learning (Bloomsbury Education, £14.99).

Dylan Wiliam is emeritus professor of educational assessment at the UCL Institute of Education; for more information, visit dylanwiliam.org or follow @dylanwiliam.

Naomi Barker is the author of The Teacher Journal (Bloomsbury). She is assistant headteacher at a school in London.

Ben Fuller is lead assessment adviser and Felicity Nichols is SEND adviser at HFL Education.

Assessment for learning examples

Put all this theory into practice with the assessment for learning examples and activities in this KS4 English lesson from head of English, Jennie Saliba. It combines active learning and independent study with peer and self assessment. Learners will have a go at editing and improving their own work while also assessing others’ writing.

‘Assessment of’ vs ‘assessment for’ vs ‘assessment as’

Assessment of learning is summative and evaluates overall achievement at the end of a period. We can define assessment for learning as formative. It involves providing feedback to improve ongoing teaching and learning. On the other hand, assessment as learning encourages self-assessment and focuses on students’ active role in their own learning process.

What counts as assessment for learning?

Different people define formative assessment in different ways. Here, Dylan Wiliam sets out an inclusive framework to explain how he defines it…

Some writers have suggested ‘assessment for learning’ focuses on the teacher’s role whereas we should call involving students in assessing their own learning ‘assessment as learning’.

Some believe that we should include students assessing each other, while others don’t.

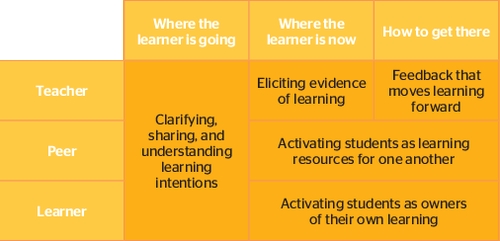

In order to develop an inclusive framework, more than ten years ago Marnie Thompson and I suggested that we can think of formative assessment as involving three processes in learning:

- where the learner is going

- where the learner is now

- how to get there

If we then think of the role of the teacher, the learner and her or his peers, we get a 3 x 3 table. We can combine certain cells within this to produce the figure below:

Assessment for learning and the EEF

In 2010 the Educational Endowment Foundation first published its Teaching and Learning Toolkit, which examined research from all over the world in terms of its quality and relevance for classroom practice, the cost of implementation, and the impact on student achievement.

It concluded that the three most cost-effective interventions were:

- feedback

- helping learners become more active owners of their own learning

- collaborative or cooperative learning

These are, of course, three of the five strategies of formative assessment identified in the table above.

The other two formative assessment strategies are necessary precursors to these three. You can’t give feedback until you find out what is going wrong (or indeed, right), so you have to elicit evidence of what it is that students have learned.

And you don’t know what evidence to elicit until you know what it is you want students to learn. In this sense, the five strategies of formative assessment form a minimum set of requirements for improving student learning.

Put simply, if you want to raise student achievement, right now there is nothing we know of that will have a bigger impact than developing the use of formative assessment.

How to tell if your assessment for learning strategies are working

David Spendlove offers some advice on how to gauge whether your assessment for learning strategies are having the desired effect…

1 | Evidence-based teaching?

To embed ideas into our teaching repertoire, it requires extended practice over time and a willingness to commit to such practice. Where possible, we should develop such practices in an informed way and as part of an evidence-based approach.

Therefore, rather than relying upon subjective observations alone, collect data where possible and use it in an informed way. Evidence-based approaches using peer-to-peer observations are about empowering teachers, not simply about catching them out!

2 | Whole-school commitment

If we are to actively use assessment for learning strategies in school, there needs to be a whole-department or whole-school commitment. Ensuring that assessment for learning is a standing item on the agenda of meetings is a way of keeping it a priority.

Build assessment for learning into school and departmental development plans with clear targets that you monitor. Provide opportunities to share good practice and learn from each other through coaching and mentoring. This ensures that you embed assessment for learning sustainably.

3 | Measure the effect size

Whilst we may have an intuitive feel for what works and what doesn’t, what evidence can we draw upon to give us a better idea of where we should be placing our effort? One way that teachers can increase their understanding is through looking at the research on ‘effect sizes’.

If we compare two or more intervention groups, effect sizes tell us which one is likely to have a greater effect on the learner. Effect size often works by drawing upon multiple studies and effectively provides an average of those studies.

4 | Teachers as researchers

Examining the learning outcomes of an implementation is a good way of finding out whether or not something has been successful. Many teachers view research in the wrong way. My view of research is that it is a systematic way of finding something out. It is planned, and there is going to be some evidence to discuss.

Evidence-based teaching is not simply passing on research for teachers to implement. It is about teachers being discerning and making professional judgements based upon the evidence they have access to.

More assessment for learning resources

- The Learning Scientists website is an excellent starting point to learn more about cognitive science and its place in the classroom. It contains a range of accessible information and resources for teachers, designed by psychological cognitive scientists.

- Responsive Teaching, a book by Harry Fletcher-Wood, explains the benefits of shared planning with colleagues.

- Download our activity and reflection sheet and use it to help structure how you can implement the principles of assessment for learning in your classroom.